There are filmmakers who entertain, filmmakers who provoke, and filmmakers who challenge. Then there is Anders Thomas Jensen, a Danish writer-director who does all three with such deceptive ease that it’s almost criminal how little recognition he receives outside Scandinavia. To call Jensen a master of dark comedy would be accurate but insufficient. He is an architect of human absurdity, a cartographer of moral ambiguity, and perhaps most remarkably, a comedian who makes you laugh at the darkest corners of the human condition without ever feeling like you’ve compromised your soul in the process.

For those who have experienced the privilege of watching his films, Jensen represents something rare in contemporary cinema: a filmmaker with a completely unique voice, instantly recognizable yet endlessly surprising. His films exist in a tonal space that shouldn’t work, balancing pitch-black comedy with genuine pathos, extreme violence with tender humanity, absurdist scenarios with emotional authenticity. And yet, they don’t just work—they soar.

The Craft of Darkness: Jensen’s Unparalleled Writing

Before we dive into his directorial work, we must acknowledge that Anders Thomas Jensen was already a legend before he ever stepped behind the camera. As a screenwriter, he crafted some of the most acclaimed Danish films of the late 1990s and early 2000s, working extensively with directors like Susanne Bier and collaborating on projects that would define New Danish Cinema. His screenplay for Susanne Bier’s ‘Open Hearts’ demonstrated his ability to excavate raw emotional truth, while his work on multiple shorts earned him not one but two Academy Awards for Best Live Action Short Film—for ‘Election Night’ in 1999 and ‘Helmer & Son’ in 1998.

Think about that for a moment. Two Oscars before even making a feature film. That’s not just talent—that’s a writer operating at a level of craft that borders on the supernatural. Jensen’s screenplays possess an architectural elegance, constructing narratives that feel simultaneously inevitable and surprising. His dialogue crackles with a specificity that makes even the most outlandish scenarios feel grounded. Characters speak like real people, even when they’re discussing cannibalism or contemplating revenge with a casualness that would make Tarantino envious.

What distinguishes Jensen’s writing is his profound understanding of human contradiction. His characters are never simply good or bad—they are flawed, desperate, absurd, and utterly human. They make terrible decisions for comprehensible reasons. They are capable of shocking violence and unexpected tenderness, sometimes within the same scene. This moral complexity gives his films a richness that rewards repeated viewing. You laugh at the absurdity, then realize the joke has layers, then realize those layers have foundations in genuine human psychology, and suddenly you’re not just laughing—you’re contemplating the nature of grief, masculinity, revenge, redemption, and the cosmic joke of existence itself.

The Directorial Vision: A Filmmaker is Born

Flickering Lights (2000): An Explosive Debut

Jensen’s directorial debut, ‘Flickering Lights’ (Blinkende Lygter), announced the arrival of a major filmmaking talent with the subtlety of a shotgun blast—which, given the film’s content, seems entirely appropriate. The film tells the story of four small-time Copenhagen criminals who steal money from their boss and retreat to a dilapidated restaurant in rural Jutland, intending to split the cash and go their separate ways. Naturally, nothing goes according to plan.

What could have been a conventional crime-gone-wrong narrative becomes, in Jensen’s hands, a meditation on masculinity, friendship, dreams deferred, and the possibility of redemption. The film features shocking bursts of violence that genuinely startle, yet it’s also one of the warmest films about male friendship you’ll ever see. These are violent criminals, yes, but they’re also wounded souls seeking something they can barely articulate—connection, purpose, a second chance.

The tonal shifts in ‘Flickering Lights’ shouldn’t work. One moment we’re watching brutal violence; the next, characters are earnestly discussing their dreams of opening a restaurant. But Jensen navigates these transitions with absolute confidence, never letting the film tip into parody or sentiment. The violence has consequences. The comedy emerges from character, not from jokes imposed upon them. And when the emotional moments arrive, they land with devastating impact because Jensen has earned them.

The film also marks the beginning of Jensen’s collaboration with Mads Mikkelsen, who delivers a phenomenal performance as Arne, the most volatile member of the group. Even in this early role, you can see the intensity and emotional range that would make Mikkelsen an international star. But what’s remarkable is how Jensen uses that intensity—not as spectacle, but as a window into a damaged soul seeking repair.

The Green Butchers (2003): Dark Comedy Perfected

If ‘Flickering Lights’ announced Jensen’s talent, ‘The Green Butchers’ (De Grønne Slagtere) confirmed his genius. This is, without exaggeration, one of the darkest comedies ever made—a film that finds humor in accidental cannibalism, childhood trauma, suicide, and social anxiety, yet somehow never feels cruel or exploitative. It’s a highwire act of tonal control that few filmmakers could pull off, and Jensen makes it look effortless.

The film reunites Jensen with both Mads Mikkelsen and Nikolaj Lie Kaas, who play Svend and Bjarne, two butchers who open their own shop. When a body accidentally ends up in their meat freezer and subsequently in their products, the resulting ‘chickie’ becomes wildly popular, creating a moral crisis that spirals into increasingly dark territory. But to describe the plot is to miss what makes the film extraordinary.

‘The Green Butchers’ is really a film about two profoundly lonely men trying to create something of value, trying to connect with other people, trying to overcome their pasts. Svend is haunted by childhood trauma involving his twin brother; Bjarne is crippled by social anxiety. These are deeply sad characters, and Jensen never loses sight of their humanity, even as the situations become increasingly absurd and horrifying. You laugh at the dark comedy, but you also care deeply about these men and their desperate attempts to find dignity and connection.

Mikkelsen and Kaas are phenomenal, creating a rapport that feels lived-in and genuine. Their chemistry would become a cornerstone of Jensen’s cinema, recurring in film after film. Mikkelsen plays Svend with a tightly wound energy that occasionally explodes into violence or panic, while Kaas brings a wounded gentleness to Bjarne that makes him heartbreaking even as he participates in unconscionable acts. It’s a masterclass in comedic performance that never sacrifices emotional truth for laughs.

The film’s visual style is deceptively simple—Jensen favors naturalistic lighting and unfussy camera work that lets the performances and writing take center stage. But this simplicity is deceptive; every frame is precisely composed, every cut purposeful. Jensen’s direction serves the story and characters rather than calling attention to itself, which is perhaps the hardest and most admirable approach a director can take.

Adam’s Apples (2005): Absurdist Masterpiece

With ‘Adam’s Apples’ (Adams Æbler), Jensen created what many consider his masterpiece—a film so audacious in its premise, so bold in its tonal juggling act, so profound in its thematic exploration that it stands as one of the great dark comedies in cinema history. It’s a film that asks whether faith in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary is admirable persistence or dangerous delusion, and it refuses to provide easy answers.

The plot: Adam, a neo-Nazi fresh from prison (played with terrifying intensity by Ulrich Thomsen), is assigned to a church-run rehabilitation program led by Ivan, an impossibly optimistic pastor (Mads Mikkelsen in one of his finest performances). Ivan challenges Adam to care for an apple tree until it bears fruit. Adam, eager to break Ivan’s spirit, accepts. What follows is an escalating battle between Adam’s determined nihilism and Ivan’s unshakeable faith, played out through increasingly absurd and violent circumstances.

To call ‘Adam’s Apples’ controversial is an understatement. The film features explicit violence, crude humor, challenging depictions of disability and mental illness, and a protagonist who is actively evil at the film’s beginning. Yet Jensen navigates this minefield with absolute moral clarity, never endorsing Adam’s views while also never simplifying him into a mere symbol. Adam is a fully realized human being whose worldview has been shaped by trauma and environment—understandable without being excusable.

What elevates ‘Adam’s Apples’ beyond provocation is its genuine engagement with questions of faith, suffering, and redemption. Ivan’s faith is tested not by theological arguments but by increasingly horrific real-world events—yet he maintains his optimism through what appears to be willful delusion. Is this admirable? Pathological? The film argues both simultaneously. It’s Dostoevsky reimagined as pitch-black comedy, and it works brilliantly.

Mikkelsen’s performance as Ivan is nothing short of miraculous. He could have played the character as a simple-minded fool or a saintly figure, but instead he creates something far more interesting: a man who has consciously chosen faith as a response to trauma, who maintains his worldview through sheer force of will, and whose apparent delusions might actually be the only sane response to an insane world. It’s a performance of extraordinary depth and subtlety, made all the more impressive by the absurdist context.

The supporting cast, including Nicolas Bro and Paprika Steen, is equally excellent, creating a gallery of broken people seeking redemption in the least likely place. Jensen’s script gives each character dimensionality and dignity, even as they participate in increasingly ludicrous situations. The film’s climax, involving premature labor, supernatural intervention, and a final confrontation between faith and nihilism, is simultaneously hilarious and genuinely moving—a testament to Jensen’s absolute mastery of tone.

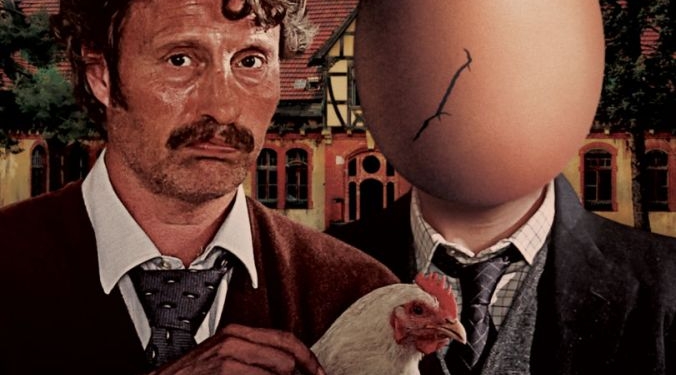

Men & Chicken (2015): Genetic Grotesquery

After a nine-year gap in his directorial output, Jensen returned with ‘Men & Chicken’ (Mænd & Høns), his most visually audacious and thematically ambitious film to date. The story follows two brothers, Gabriel and Elias (played by David Dencik and Mads Mikkelsen), who discover they were the product of genetic experiments and travel to a remote island to find their biological father and other siblings. What they discover is a household of grotesquely deformed men living in squalor, obsessed with animal husbandry, and harboring dark secrets.

‘Men & Chicken’ is Jensen’s most purely absurdist work, leaning heavily into the grotesque while maintaining the emotional core that defines his cinema. The film’s visual style is notably different from his earlier work—more stylized, more willing to embrace the artificial, more consciously cinematic in its compositions. The production design creates a world that feels disconnected from reality, appropriate for a film dealing with the consequences of playing God through genetics.

Mads Mikkelsen, buried under prosthetics and affecting a severe speech impediment, delivers yet another fearless performance for Jensen. Elias is perhaps his most pathetic character, a man-child desperate for connection and approval, capable of shocking violence yet also capable of growth and change. The physical comedy Mikkelsen brings to the role would be impressive in any context; combined with genuine emotional depth, it becomes something remarkable.

The film’s themes—genetic determinism versus free will, the nature of family, what makes us human—are heady stuff, but Jensen never allows the philosophy to overwhelm the story. These are ideas embedded in character and situation, explored through action and dialogue rather than speeches. The film’s conclusion, involving both tragedy and hope, feels earned rather than imposed, a resolution that honors the complexity of what came before.

Some critics found ‘Men & Chicken’ too strange, too grotesque, too willing to alienate audiences. These critics are wrong. The film is challenging, certainly, but it’s also hilarious, touching, and thematically rich. It’s Jensen pushing his aesthetic to new extremes while maintaining the humanism that makes his work resonate. It’s a film that demands multiple viewings to fully appreciate its layers.

Riders of Justice (2020): Action Meets Existentialism

‘Riders of Justice’ (Retfærdighedens Ryttere) might be Anders Thomas Jensen’s most accessible film, which is saying something given that it features extreme violence, mathematical theories about probability, and a profound meditation on randomness, grief, and the human need for meaning. It’s also, somehow, often hilarious—a revenge thriller that subverts genre expectations while delivering genuine thrills.

Mads Mikkelsen plays Markus, a military man whose wife is killed in a train crash. A group of misfit statisticians approaches him with a theory: the crash wasn’t an accident but an assassination attempt by a biker gang. What follows is simultaneously a revenge thriller and an exploration of how humans impose patterns on chaos, seeking meaning in randomness because the alternative—that terrible things happen for no reason—is unbearable.

The genius of ‘Riders of Justice’ is how it functions on multiple levels simultaneously. As an action film, it’s brutally effective, featuring several phenomenally choreographed sequences of violence. As a character study, it’s remarkably nuanced, with Mikkelsen delivering one of his most controlled performances as a man using violence as a shield against processing grief. As a comedy, it’s often hilarious, with the statisticians providing both comic relief and genuine insight. As a philosophical text, it’s genuinely profound, exploring questions of causality, meaning, and justice without ever becoming pretentious.

Nikolaj Lie Kaas appears as Otto, one of the statisticians, bringing his characteristic wounded earnestness to a character who might have been merely comic in lesser hands. The chemistry between Kaas and Mikkelsen, refined over multiple collaborations, gives their scenes together a lived-in quality that anchors the film’s more outlandish elements. Their relationship—the violent soldier and the anxious mathematician finding unexpected kinship—becomes the film’s emotional center.

The film’s conclusion is masterful, eschewing simple revenge-thriller satisfaction for something more complex and ultimately more satisfying. Jensen suggests that while we cannot control the random chaos of existence, we can choose how we respond to it—and that connection, forgiveness, and openness might be more powerful than vengeance. It’s a message that could feel trite, but Jensen earns it through the specificity of his characters and situations.

The Promised Land (2023): Jensen as Screenwriter

Anders Thomas Jensen’s most recent collaboration represents a return to his roots as a master screenwriter. “The Promised Land” (Bastarden), directed by Nikolaj Arcel, reunites Jensen with his frequent collaborator Arcel, with whom he has crafted some of Denmark’s most compelling narratives. The screenplay, co-written by Jensen and Arcel, is a period drama set in 18th-century Denmark, following retired military captain Ludvig Kahlen who attempts to establish a colony on the barren heath of Jutland.

Mads Mikkelsen plays Kahlen, a man of low birth determined to achieve nobility by cultivating the supposedly untamable heath. His struggle against nature is complicated by conflict with a corrupt local magistrate who sees Kahlen’s presence as a threat to his power. What emerges is a story about the cost of ambition, the cruelty of class structures, and the resilience of human determination.

While the film lacks the overt dark comedy of Jensen’s directorial work, his sensibility as a screenwriter is evident throughout. The moral complexity, the psychological acuity in rendering social dynamics, and the interest in wounded masculinity seeking redemption are all hallmarks of Jensen’s writing. The violence, when it comes, is shocking and brutal in ways that feel consistent with Jensen’s unflinching approach to human behavior. The film’s visual austerity—all muted colors and harsh landscapes—creates an atmosphere that mirrors the characters’ internal struggles.

The film received widespread critical acclaim and was selected as Denmark’s entry for Best International Feature Film at the 96th Academy Awards, ultimately receiving a nomination. This recognition highlights the continued power of Jensen’s screenwriting, demonstrating that his ability to craft complex, morally ambiguous characters and narratives extends across genres and directorial visions.

What’s most impressive is how Jensen’s writing translates across different directorial styles. Working with Arcel, Jensen helped craft a historical epic that maintains thematic consistency with his own directorial work while allowing Arcel’s distinct visual approach to shine. It’s a testament to Jensen’s versatility as a writer—his themes and character insights are strong enough to work in both his own darkly comedic contemporary films and in sweeping period dramas helmed by other directors.

The Mikkelsen-Kaas Connection: Collaborators Extraordinaire

One cannot discuss Anders Thomas Jensen without examining his extraordinary working relationships with Mads Mikkelsen and Nikolaj Lie Kaas. These are not simply recurring collaborations—they represent one of the great actor-director relationships in contemporary cinema, comparable to Scorsese and De Niro, or Kurosawa and Mifune.

Mads Mikkelsen has appeared in every single one of Jensen’s feature films, taking on wildly different roles that showcase his extraordinary range. From the volatile Arne in ‘Flickering Lights’ to the delusional optimist Ivan in ‘Adam’s Apples,’ from the grotesque Elias in ‘Men & Chicken’ to the grief-stricken soldier Markus in ‘Riders of Justice,’ Mikkelsen has demonstrated a willingness to risk everything for Jensen’s vision. He disappears into these characters, finding the humanity in even the most extreme circumstances.

What’s remarkable is how Jensen writes for Mikkelsen’s specific talents—his intensity, his physical presence, his ability to convey complex emotions through minimal expressions. You can feel Jensen pushing Mikkelsen in each film, asking him to go further, darker, stranger. And Mikkelsen responds with performances that are fearless in their commitment. Their collaboration has given us some of the most compelling characters in modern cinema.

Nikolaj Lie Kaas, appearing in most of Jensen’s films, brings a different energy—more neurotic, more openly vulnerable, often serving as the emotional center that grounds the darker elements. The chemistry between Kaas and Mikkelsen is palpable; you believe these are people with history, with genuine connections. Their scenes together crackle with an authenticity that comes only from deep trust and repeated collaboration.

Jensen has spoken about how he writes with these actors in mind, how their input shapes the final scripts, how the rehearsal process involves genuine collaboration. This shows in the final products—these performances never feel imposed upon the actors but rather organically discovered through the creative process. It’s a working method that recalls the great European auteurs who built stock companies of trusted collaborators.

The Jensen Style: Darkness, Absurdity, and Humanism

What defines a Jensen film? Beyond the obvious elements—dark comedy, violent outbursts, existential themes—there’s something more essential at work. Jensen’s films are characterized by a profound humanism that never wavers, even in the darkest moments. His characters may do terrible things, may find themselves in absurd situations, may be grotesque or damaged or violent, but they are never less than human. Jensen sees them with clarity but also with compassion.

This humanism manifests in the details: the way a violent criminal earnestly discusses his dream of opening a restaurant, the way a neo-Nazi gradually opens himself to connection, the way damaged men find family among other damaged men. Jensen understands that people are contradictions, that we are all capable of both cruelty and kindness, that our worst actions often stem from our deepest wounds.

His visual style serves this humanism. Jensen generally avoids flashy cinematography, preferring naturalistic lighting and unfussy compositions that keep the focus on performance and character. When violence erupts, it’s shocking not because it’s stylized but because it’s sudden and brutal—a rupture in the fabric of everyday life. The contrast between the mundane and the extreme creates the distinctive Jensen tone.

The absurdism in Jensen’s work serves a purpose beyond mere shock value. By pushing situations to extremes, by introducing elements of the grotesque and ridiculous, Jensen strips away social niceties to reveal underlying human truths. The absurdity becomes a lens through which we can examine questions that might be too painful to confront directly: What makes a life meaningful? Can anyone be redeemed? How do we find connection in an indifferent universe?

Jensen’s films often feature characters seeking redemption or transformation, but he never suggests that change is easy or complete. His endings tend toward ambiguity—not because he’s afraid to commit to a resolution, but because he understands that real life doesn’t offer neat conclusions. People muddle through. They make progress and backslide. They find moments of grace among the chaos. This feels more honest than traditional narrative resolution, and infinitely more meaningful.

Why Jensen Matters: The Case for Recognition

It’s genuinely baffling that Anders Thomas Jensen isn’t more widely recognized as one of the great filmmakers of his generation. His body of work demonstrates absolute mastery of craft, thematic consistency combined with formal innovation, and a distinctive vision that has remained uncompromising across multiple films. He has created a filmography without a weak entry, with each film building on and deepening the concerns of its predecessors.

Perhaps part of the issue is language—Danish cinema doesn’t penetrate international markets the way French or even Swedish films do. Perhaps it’s the darkness of the comedy, which can alienate viewers unprepared for Jensen’s tonal extremes. Perhaps it’s simply the randomness of cultural attention, which often has little to do with actual merit. Whatever the reason, it’s a crime that Jensen isn’t mentioned in the same breath as the Coen Brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson, or other contemporary masters.

Because Jensen deserves that recognition. His films reward repeated viewing, revealing new layers each time. His understanding of human psychology is profound. His ability to balance competing tones without compromise is extraordinary. His collaborations with actors have produced some of the finest performances in modern cinema. His willingness to take risks, to push into uncomfortable territory, to refuse easy answers—these are the marks of a true artist.

‘The Promised Land’s’ Oscar nomination may represent a turning point, an opportunity for international audiences to discover Jensen’s work. But even if widespread recognition never comes, Jensen’s films will endure. They speak to something essential about the human experience—our capacity for violence and tenderness, our need for meaning in a random universe, our desperate search for connection and redemption. These are timeless concerns, rendered with singular vision and uncompromising artistry.

The Future: What’s Next for Jensen?

As of this writing, Jensen shows no signs of slowing down. At an age when many filmmakers settle into comfortable patterns, he continues to challenge himself with new genres and approaches. ‘The Promised Land’ demonstrates his ability to work in more conventional forms without sacrificing his distinctive voice. One can only imagine what he might tackle next.

Will he return to contemporary dark comedy, the mode in which he’s most comfortable? Will he continue exploring historical material? Might he attempt something in English, potentially expanding his international reach? Whatever direction he chooses, if his past work is any indication, it will be uncompromising, challenging, darkly funny, and profoundly human.

The hope is that ‘The Promised Land’s’ success opens doors, that more people discover Jensen’s earlier work, that his influence on contemporary cinema becomes more widely acknowledged. Because Jensen has been quietly making masterpieces for over two decades, and it’s past time for the world to notice.

Conclusion: A Personal Testament

As someone who has watched all of Jensen’s films multiple times, who has spent countless hours thinking about their themes and techniques, who has evangelized to friends and students about his genius, I can say without exaggeration that Anders Thomas Jensen has enriched my understanding of what cinema can do. His films have made me laugh harder, think deeper, and feel more intensely than almost any other contemporary filmmaker’s work.

Each Jensen film is a masterpiece in its own right, but together they form a body of work that is greater than the sum of its parts—a sustained meditation on human nature, rendered with dark humor and genuine compassion. From ‘Flickering Lights’ through ‘The Promised Land,’ Jensen has never made a false step, never compromised his vision, never settled for easy answers or comfortable conclusions.

In an era of safe, sanitized mainstream cinema, Jensen’s films feel dangerous and alive. They acknowledge the darkness of existence without succumbing to nihilism. They find humor in horror without minimizing suffering. They suggest the possibility of redemption without guaranteeing it. They are, in short, films for adults—complicated, challenging, and utterly rewarding.

If you haven’t experienced Anders Thomas Jensen’s work, you have a rare gift ahead of you: the discovery of a major filmmaker working at the height of his powers. Start anywhere—each film stands on its own—but make sure you watch them all. These are films that will stay with you, films that reveal new dimensions with each viewing, films that understand something essential about what it means to be human.

Anders Thomas Jensen is not just a master of dark comedy, though he is certainly that. He is a master filmmaker, period—one whose work deserves to be celebrated, studied, and treasured. His collaboration with Mads Mikkelsen and Nikolaj Lie Kaas has produced some of the finest performances and films in modern cinema. His understanding of human psychology is profound. His craft is impeccable. His vision is unique.

In other words, Anders Thomas Jensen is a genius. And it’s time the world recognized it.