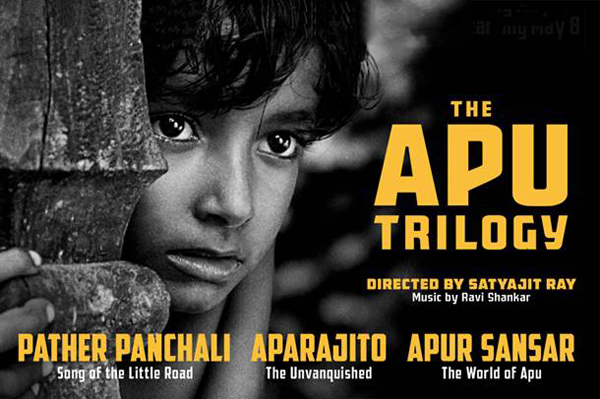

Few works in the history of cinema have captured the essence of human experience with the quiet power and profound simplicity of The Apu Trilogy. Directed by Satyajit Ray, an Indian filmmaker whose name would become synonymous with artistic brilliance, the trilogy—comprising Pather Panchali (1955), Aparajito (1956), and Apur Sansar (1959)—stands as a towering achievement in global cinema. Spanning the life of Apu, a boy born into poverty in rural Bengal, the trilogy traces his journey through loss, growth, and self-discovery against the backdrop of a rapidly changing India. Rooted in neorealism yet imbued with a distinctly lyrical quality, Ray’s trilogy transcends cultural boundaries to speak universally about the human condition.

This article delves into the origins of The Apu Trilogy, its narrative and thematic depth, the innovative filmmaking techniques that brought it to life, and its lasting impact on cinema and audiences worldwide.

Origins and Inspiration

Satyajit Ray’s journey to creating The Apu Trilogy was as unconventional as the films themselves. Born in 1921 into a prominent Bengali family with a rich artistic heritage, Ray initially pursued a career in commercial art. However, his passion for cinema grew after he encountered the works of European auteurs like Jean Renoir and Vittorio De Sica. It was De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), a cornerstone of Italian neorealism, that profoundly influenced Ray, inspiring him to tell authentic stories about ordinary lives with minimal artifice.

The trilogy is adapted from two novels by Bengali author Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay: Pather Panchali (The Song of the Little Road) and its sequel Aparajito (The Unvanquished). Ray first encountered Pather Panchali while illustrating an abridged edition of the book in the early 1940s. The story of Apu, a boy navigating the joys and sorrows of rural life, resonated deeply with Ray, who saw in it a reflection of his own cultural roots and a vehicle to explore universal themes. However, adapting these literary works into films was no small feat for a first-time director with no formal training in filmmaking.

Ray faced significant challenges in bringing his vision to life. Lacking funds and industry support, he assembled a crew of amateurs and relied on personal savings and small loans to begin shooting Pather Panchali. The production was famously protracted, spanning three years due to financial constraints, with Ray and his team filming sporadically whenever resources allowed. Cinematographer Subrata Mitra, a still photographer with no prior experience in motion pictures, and composer Ravi Shankar, who scored the film in a single night, were among the novices who contributed to this unlikely triumph. The result was a film that defied its modest origins to become a global sensation.

Narrative and Thematic Depth

The Apu Trilogy unfolds as a bildungsroman, chronicling Apu’s evolution from childhood to adulthood across three distinct yet interconnected films. Each installment stands alone as a complete story while contributing to the larger arc of Apu’s life, creating a tapestry of emotional resonance and philosophical inquiry.

Pather Panchali: The first film introduces us to Apu (Subir Banerjee) as a wide-eyed child in a rural Bengali village. The narrative centers on his family—his father Harihar, a struggling priest and poet; his mother Sarbajaya, burdened by poverty; and his spirited older sister Durga. The film’s episodic structure captures the rhythms of village life: the monsoon rains, the theft of fruit from a neighbor’s orchard, the fleeting joy of a traveling jatra performance. Yet beneath this simplicity lies a poignant exploration of loss. Durga’s death from illness, a consequence of the family’s inability to afford proper care, shatters their fragile world, forcing them to leave the village. The film’s final image—of the family departing in a cart as Apu gazes back—sets the tone for his journey of resilience.

Aparajito: The second chapter follows an adolescent Apu (Pinaki Sengupta, later Smaran Ghosal) as the family relocates to Varanasi after Harihar’s death. Here, Ray examines the tension between tradition and modernity. Apu excels in school, earning a scholarship to study in Kolkata, but his ambition strains his relationship with Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee), who clings to the past. Her loneliness and eventual death underscore the cost of Apu’s pursuit of independence. The film’s title, meaning “The Unvanquished,” reflects Apu’s determination to forge his own path, even as it isolates him from his roots.

Apur Sansar: In the trilogy’s conclusion, an adult Apu (Soumitra Chatterjee) emerges as a sensitive, introspective man grappling with love, loss, and responsibility. After a chance marriage to Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), Apu finds fleeting happiness, only to lose her to childbirth complications. Devastated, he abandons his son Kajal and wanders aimlessly until a transformative reunion years later compels him to embrace fatherhood. Apur Sansar (The World of Apu) completes Apu’s arc, blending tragedy with a tentative hope for redemption.

Thematically, the trilogy explores the interplay of fate and agency, the inevitability of change, and the enduring power of human connection. Ray portrays poverty not as a melodramatic device but as a lived reality that shapes his characters’ choices and relationships. The films also reflect India’s transition from a rural, tradition-bound society to an urban, modern one—a shift mirrored in Apu’s own trajectory. Yet Ray’s focus remains intimate, grounding these grand themes in the specificities of Apu’s emotional world.

Cinematic Techniques and Aesthetic Innovation

Ray’s filmmaking in The Apu Trilogy is a masterclass in economy and expressiveness, blending neorealist principles with a poetic sensibility unique to his vision. Working with limited resources, he and his team pioneered techniques that elevated the films beyond their humble production values.

In Pather Panchali, Ray eschewed studio sets for real locations, shooting in the village of Boral to capture the texture of rural life. Natural light and handheld camerawork lent an immediacy to the visuals, while Subrata Mitra’s innovative use of bounce lighting—reflecting sunlight off cloth to illuminate indoor scenes—created a soft, naturalistic glow. The film’s pacing, slow and deliberate, mirrors the unhurried rhythm of its setting, allowing viewers to inhabit the characters’ world.

Music plays a pivotal role in the trilogy, with Ravi Shankar’s sitar-based score for Pather Panchali weaving a haunting leitmotif that evokes both joy and melancholy. In later films, Ray took over composing duties himself, tailoring the soundscapes to Apu’s evolving emotional landscape. The famous train sequence in Pather Panchali, where Apu and Durga run through fields to glimpse a passing locomotive, exemplifies Ray’s synergy of image and sound: the whistle of the train, the rustle of grass, and Shankar’s music fuse into a moment of pure cinematic poetry.

Ray’s use of non-professional actors—many of whom had never faced a camera before—further enhances the trilogy’s authenticity. Chunibala Devi, an 80-year-old former theater actress, delivers a heartrending performance as the elderly aunt Indir in Pather Panchali, her weathered face embodying the weight of time. Similarly, Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore, both debutants in Apur Sansar, bring a raw vulnerability to their roles, their chemistry palpable despite their inexperience.

Ray’s editing is equally masterful, favoring long takes and subtle transitions over dramatic cuts. In Aparajito, the dissolve from Sarbajaya’s deathbed to a flock of birds taking flight symbolizes her release from suffering—a visual metaphor that lingers in the mind. Such moments reveal Ray’s ability to convey complex emotions with minimal flourish, trusting the audience to interpret the silences between words and images.

Global Impact and Legacy

When Pather Panchali premiered at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, it stunned audiences and critics alike, winning the Best Human Document award and heralding Ray’s arrival on the world stage. Western filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Akira Kurosawa praised its humanity and craftsmanship, with Kurosawa famously remarking, “Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.” The trilogy introduced Indian cinema to a global audience, challenging stereotypes of Bollywood extravagance and showcasing the richness of regional storytelling.

The films’ influence reverberates through modern cinema. Directors like Wes Anderson (The Darjeeling Limited) and Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire) have cited Ray as an inspiration, particularly his ability to blend cultural specificity with universal appeal. The trilogy’s neorealist roots also echo in contemporary works like Sean Baker’s The Florida Project, which similarly finds beauty in marginalized lives.

Beyond its artistic legacy, The Apu Trilogy holds a mirror to societal issues—poverty, gender roles, education—that remain relevant today. Sarbajaya’s struggles as a widowed mother, for instance, highlight the precarious status of women in patriarchal systems, while Apu’s education reflects the transformative potential of knowledge amid systemic inequality.

Preservation efforts have ensured the trilogy’s survival. After a 1993 fire destroyed the original negatives, a meticulous restoration by the Criterion Collection and the Academy Film Archive, completed in 2015, revived the films in pristine quality, allowing new generations to experience their magic.

Conclusion

The Apu Trilogy is more than a cinematic achievement; it is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the power of art to transcend barriers. Satyajit Ray, with his untrained eye and unwavering vision, crafted a saga that feels both deeply personal and universally relatable. Through Apu’s eyes, we witness the beauty and brutality of life, the ache of loss, and the quiet strength to endure. Sixty years after its debut, the trilogy remains a beacon of storytelling—an indelible reminder that the simplest tales, told with honesty and heart, can resonate across time and borders.

Excellent read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing a little research on that. And he actually bought me lunch because I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!