There exists a particular species of filmmaker who operates in the margins of mainstream Hollywood, crafting work so distinctive and influential that it essentially creates its own genre. Christopher Guest is precisely that kind of artist. For those of us who have spent countless hours rewatching his films, dissecting every improvised line and perfectly-timed reaction shot, Guest represents something rare in contemporary cinema: a filmmaker with an utterly singular voice, an unwavering commitment to his craft, and a body of work that has fundamentally reshaped how we think about comedy on screen.

Guest didn’t invent the mockumentary format, but he perfected it, elevating what could have been a simple comedic conceit into something approaching high art. His films are masterclasses in observational humor, character development, and ensemble performance. They reward repeated viewing in ways that traditional comedies rarely do, revealing new layers of absurdity and pathos with each encounter. And for those of us who consider ourselves students of the form, his work represents an inexhaustible wellspring of craft lessons and pure joy.

The Foundation: From Stage to Screen to Spinal Tap

Christopher Haden-Guest was born in New York City in 1948, though he spent formative years in England, where he would eventually inherit the title of 5th Baron Haden-Guest. This transatlantic upbringing may have contributed to his particular gift for cultural observation, the slight remove from purely American sensibilities that allows him to examine his subjects with both affection and gentle mockery. But it was in the comedy trenches of 1970s New York and Los Angeles where Guest truly developed his artistic voice.

His early career included work with the National Lampoon Radio Hour alongside future comedy legends, television appearances, and roles in films like “The Long Riders” and “Heartbeeps.” But nothing in his résumé suggested what was coming. Guest was talented, certainly, but he seemed destined to be a reliable character actor rather than a transformative filmmaker.

Then came “This Is Spinal Tap” in 1984.

While directed by Rob Reiner, “Spinal Tap” was co-written by Guest, who also delivered an iconic performance as Nigel Tufnel, the lead guitarist whose amplifiers famously go to eleven. The film’s impact cannot be overstated. It didn’t just satirize rock documentaries; it captured something essential about artistic delusion, the gap between self-perception and reality, and the tragicomic nature of faded glory. Heavy metal bands began to refer to unfortunate touring mishaps as “Spinal Tap moments.” The film entered the cultural lexicon in a way that few comedies ever do.

What made “Spinal Tap” revolutionary wasn’t just its documentary style or its musical parody, though both were executed brilliantly. It was the film’s commitment to its reality, the way it allowed absurdity to emerge organically from character rather than forcing jokes onto situations. The famous Stonehenge scene, where a stage prop arrives at eighteen inches rather than eighteen feet due to a confusion between feet and inches on a napkin drawing, works because everyone involved treats it with complete seriousness. There’s no winking at the camera, no acknowledgment that we’re watching a comedy. The humor emerges from the commitment.

Guest absorbed these lessons deeply. When he finally stepped behind the camera as sole director, he would refine this approach into something even more remarkable.

Waiting for Guffman: The Template Crystallizes

“Waiting for Guffman,” released in 1996, announced Guest as a major directorial talent and established the template he would follow for his subsequent masterworks. Set in the small Missouri town of Blaine, the film follows the creation of “Red, White and Blaine,” a musical celebrating the town’s sesquicentennial, and the community theater participants who dream of being discovered by a New York theatrical agent named Guffman.

The genius of “Guffman” lies in how Guest observes these characters. Corky St. Clair, played by Guest himself, is a flamboyant director whose claims of Off-Off-Broadway experience are transparently embellished. Ron and Sheila Albertson (Fred Willard and Catherine O’Hara) are a married couple whose enthusiasm vastly exceeds their talent. Libby Mae Brown (Parker Posey) works at the Dairy Queen and sees the show as her ticket out of Blaine. Dr. Allan Pearl (Eugene Levy) is a dentist with musical theater dreams.

These could have been cruel caricatures. In lesser hands, they would have been targets for mockery, small-town rubes to be laughed at from a position of urban superiority. But Guest does something far more sophisticated and humane. He observes these people with genuine affection even as he captures their delusions and limitations. We laugh at them, certainly, but we also recognize ourselves in them—our own aspirations that exceed our abilities, our own need to be seen and appreciated, our own willingness to invest deeply in things that others might consider trivial.

The improvisational approach Guest employed on “Guffman” would become his signature. Working from a detailed outline rather than a traditional script, he allowed his ensemble cast to find their characters through improvisation. This created dialogue that felt genuinely spontaneous, with overlaps, interruptions, and verbal tics that scripted comedy rarely captures. Watch how Catherine O’Hara layers her performance with small character details—the way Sheila touches Ron’s arm, her slightly forced laughter at her own observations, the particular vocal quality she adopts when discussing their stint on a cruise ship.

The film also established Guest’s visual aesthetic. His mockumentaries are shot in a deliberately understated style, with minimal camera movement and natural lighting. There are no elaborate setups or flashy techniques to distract from the performances. The camera observes, sometimes from slightly awkward angles, capturing moments that feel stolen rather than staged. This creates an authenticity that makes the absurdity even funnier.

Perhaps most importantly, “Guffman” demonstrated Guest’s understanding of structure. The film builds beautifully toward the actual performance of “Red, White and Blaine,” and when we finally see it, it’s both terrible and strangely moving. The songs are genuinely catchy (thank you to Guest’s musical collaborators Michael McKean and Harry Shearer), the costumes are enthusiastic disasters, and the performers commit fully to their amateur production. We’ve spent the entire film getting to know these people, and now we’re watching their dreams—however modest or misguided—actually happen. It’s the perfect encapsulation of Guest’s approach: laugh, but also care.

Best in Show: Perfection in the Form

If “Guffman” established the template, “Best in Show” (2000) represents the form at its absolute peak. Following a group of dog owners preparing for and competing in the prestigious Mayflower Kennel Club Dog Show, the film is a miracle of structure, character work, and cumulative humor.

The ensemble here is spectacular, with each handler-dog pair functioning as their own complete comic universe. There’s the yuppie power couple (Parker Posey and Michael Hitchcock) whose neurotic Weimaraner has been traumatized by seeing them have sex. The Southern good ol’ boys (Guest and Michael McKean) who fish and hunt with their Bloodhound. The wealthy, eccentric socialite (Catherine O’Hara) with her poodle and her even more eccentric new husband (Eugene Levy). The aspiring handler (Jennifer Coolidge) with her standard poodle and her intimidatingly accomplished husband. The buttoned-up catalogue model couple (Michael McKean and John Michael Higgins) with their matching Shih Tzus.

What’s remarkable about “Best in Show” is how Guest manages to give each of these storylines space to develop while maintaining perfect narrative momentum. The film feels loose and observational, yet it’s actually tightly structured, with careful attention to pacing and payoff. Early character details reappear later with perfect timing. The catalogue couple’s habit of discussing everything in outdoor catalogue terms becomes a running gag that never wears out. O’Hara’s character’s past as a “conga line of former lovers” pays off beautifully at the dog show itself.

The performances in “Best in Show” showcase how deeply Guest’s regular collaborators understand his approach. Watch Eugene Levy as Gerry Fleck, a two-left-footed man (literally) with a past even more colorful than his wife’s. Levy plays him with such gentle befuddlement, never pushing for laughs but finding humor in simple reactions. When former lovers of his wife begin appearing at the dog show, his resigned acceptance is heartbreaking and hilarious simultaneously.

Catherine O’Hara’s Cookie Fleck is one of the great comedic performances in modern cinema. She creates a fully-realized person—brassy, unapologetic, genuinely affectionate toward her husband despite her wild past. The way she greets each former lover with specific memories and complete lack of shame is masterful character work. O’Hara understands that Cookie isn’t playing a joke; she’s being completely authentic to her own experience.

And then there’s Fred Willard as Buck Laughlin, the clueless television commentator paired with the increasingly exasperated professional announcer (Jim Piddock). Willard’s performance is a high-wire act of comic improvisation. His inane observations and inappropriate questions feel genuinely spontaneous, and Piddock’s reactions—his barely contained horror at what’s coming out of his colleague’s mouth—create one of the great comic duos in Guest’s filmography.

The actual dog show sequences are brilliantly staged. Guest captures the peculiar world of competitive dog showing with authentic detail—the grooming areas, the waiting zones, the particular language of the judges. But he also understands the absurdity inherent in humans projecting so much meaning onto their relationships with animals. The dogs themselves are magnificently indifferent to the drama swirling around them, which only makes everything funnier.

“Best in Show” also features one of Guest’s most poignant endings. Not everyone succeeds at the dog show, and the film doesn’t tie everything up neatly. Some characters find unexpected happiness, others continue their delusions, and a few discover new obsessions to replace old ones. It’s messy and human and perfect.

A Mighty Wind: Adding Melancholy to the Mix

“A Mighty Wind” (2003) represents Guest’s most emotionally complex work, a mockumentary about aging folk musicians reuniting for a memorial concert. The film maintains all of Guest’s observational humor and character-based comedy, but it’s also genuinely moving in ways that his previous films only hinted at.

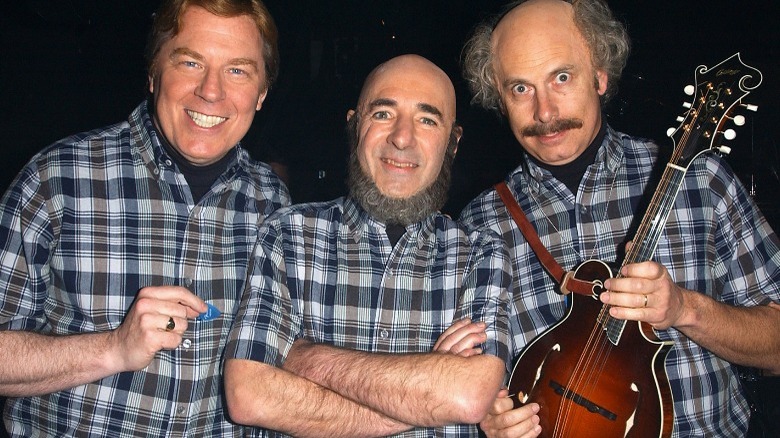

The film follows three folk acts from the 1960s: The Folksmen (Guest, McKean, and Shearer), a Kingston Trio-style group who never quite made it big; The Main Street Singers (a New Christy Minstrels parody), an aggressively wholesome ensemble; and Mitch & Mickey (Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara), a romantic duo whose personal relationship ended along with their professional one.

The Mitch & Mickey storyline gives the film its emotional weight. Levy plays Mitch Levinson as a man who has never quite recovered from his folk music fame or his relationship with Mickey. There are hints of mental health struggles, of time lost, of a life that peaked decades ago. It’s a remarkably vulnerable performance from Levy, who brings real pathos to a character who could have been simply pathetic.

O’Hara’s Mickey is now married to someone else, has a family, and has moved on. But there’s something unresolved between her and Mitch, a connection that never quite died. When they perform their signature song “A Kiss at the End of the Rainbow” at the memorial concert, it’s one of the most genuinely affecting moments in any Guest film. Will they kiss at the end, as they always did during their performing days? The anticipation builds, and Guest lets the moment breathe, giving it real weight.

The song itself, written by Guest and McKean, is legitimately beautiful—a perfect parody of 1960s folk love songs that’s also a genuinely moving piece of music. This encapsulates what Guest does so well: he can simultaneously honor and gently mock something, finding the absurdity without losing sight of what made it meaningful in the first place.

“A Mighty Wind” is filled with these kinds of moments. The Folksmen’s reunion finds them dealing with ego clashes and the reality that their music belongs to a different era. The Main Street Singers’ relentless positivity barely masks their mediocrity. Every character is dealing with the gap between who they were and who they’ve become, between their peak moments and their present reality.

The film also features some of Guest’s sharpest satirical observations. The folk music industry’s self-seriousness, the way nostalgia can preserve mediocrity as if it were excellence, the peculiar dynamics of bands where everyone has a specific role to play—all of it is captured with precision and wit.

What makes “A Mighty Wind” special in Guest’s filmography is that it dares to be sentimental alongside satirical. The memorial concert actually works as a concert. The songs are good. The performances, while imperfect, are heartfelt. Guest allows his characters their moment of triumph, however small or temporary. It’s a generous film, ultimately, about people who made art that mattered to them and to others, even if the wider world has largely forgotten.

The Ensemble: Guest’s Repertory Company

It’s impossible to discuss Guest’s work without focusing on his extraordinary ensemble of actors. While he’s occasionally brought in new performers, Guest largely works with the same core group across his films. This repertory company approach allows for a level of trust and experimentation that would be difficult to achieve with constantly changing casts.

Eugene Levy is Guest’s most essential collaborator. Across “Guffman,” “Best in Show,” “A Mighty Wind,” and “For Your Consideration,” Levy creates completely distinct characters, each with their own particular energy and vulnerability. What unites them is Levy’s gift for finding the humanity in delusion, the dignity in failure, the sweetness in desperation. His characters are never just jokes. They’re people with inner lives, hopes, disappointments, and a particular way of moving through the world.

Levy is also Guest’s co-writer on several films, helping to shape the narratives and characters even before improvisation begins. This writing partnership is crucial to understanding why Guest’s films work so well. Levy brings a particular sensitivity to character motivation and emotional truth that balances Guest’s more observational, satirical instincts.

Catherine O’Hara is the other indispensable member of Guest’s company. Her range within these films is astonishing. Sheila Albertson in “Guffman” is all nervous energy and forced enthusiasm. Cookie Fleck in “Best in Show” is brassy and confident. Mickey in “A Mighty Wind” is more grounded and wistful. In “For Your Consideration,” she plays a longtime television actress desperately hoping for recognition. Each performance is completely committed, with O’Hara creating distinct vocal patterns, physical mannerisms, and emotional cores for every character.

O’Hara also has an uncanny ability to find the perfect line reading, the ideal inflection that makes a line infinitely funnier or more poignant than it might have been. Listen to her work in any Guest film and you’ll hear a master craftsperson at work, making choices that feel completely natural while being precisely calibrated for maximum effect.

Fred Willard brings a different kind of energy to Guest’s films. His characters are often confidently clueless, speaking with authority about things they don’t understand. In “Best in Show,” his Buck Laughlin is a masterclass in comedic improvisation, with Willard generating laugh after laugh through sheer commitment to his character’s obliviousness. In “A Mighty Wind,” his manager character has similar blind confidence. Willard’s gift is making stupidity charming rather than grating, finding the childlike quality in adult obliviousness.

Parker Posey brings intensity to Guest’s films. Her characters are wound tight, operating at a higher emotional pitch than those around them. This creates wonderful comic friction, as her neurotic energy bounces off the more laid-back characters. In “Guffman,” she’s desperate to escape small-town life. In “Best in Show,” she’s convinced her dog’s neuroses are psychological rather than behavioral. Posey commits completely to these perspectives, never indicating that she’s in on the joke.

The other regular members of Guest’s company—Michael McKean, Harry Shearer, Bob Balaban, Jennifer Coolidge, Jane Lynch, John Michael Higgins, Ed Begley Jr., and others—each bring their own particular gifts. What’s remarkable is how Guest uses them, often casting them against type or finding new dimensions to their established personas. McKean, for instance, is completely different in each Guest film, from the good ol’ boy in “Best in Show” to the cynical Folksman in “A Mighty Wind.”

This ensemble approach creates several advantages. First, the actors understand Guest’s improvisational method and have developed the skills to work within it. They know how to stay in character while remaining spontaneously responsive to their scene partners. Second, the returning actors develop a shorthand with each other, creating genuine chemistry that reads on screen. Third, Guest can rely on these actors to inhabit fully-formed characters without extensive rehearsal or discussion. He trusts them, and that trust shows in the performances.

The Method: Improvisation as Craft

Guest’s improvisational approach deserves deeper examination because it’s often misunderstood. Some assume his films are made up entirely on the spot, that actors just show up and say whatever comes to mind. The reality is far more sophisticated.

Guest begins with extensive outlining. He and his co-writer (usually Levy) develop detailed character backgrounds, story structure, and specific scenes. Every major story beat is planned. The actors receive these outlines along with information about their characters—backgrounds, relationships, motivations, specific character traits.

Then comes rehearsal. Guest and his cast workshop the material, exploring the characters and relationships. This isn’t the time for jokes or trying to be funny. It’s about understanding who these people are, how they relate to each other, what they want, and what’s preventing them from getting it.

When shooting begins, Guest provides actors with the scene’s purpose and emotional trajectory. But the actual dialogue is improvised. Scenes are often shot in long takes, allowing actors to find the rhythms of real conversation. Guest shoots far more material than he’ll ever use, knowing that the magic moments will emerge from this abundance.

This method requires tremendous skill from both director and actors. Guest must recognize when something is working, when to let a scene breathe, when to redirect. The actors must remain in character while spontaneously generating dialogue that serves the story. They can’t just be funny; they must be funny within the specific logic of their character and the scene.

The editing process is where Guest’s films truly come together. He and his editor sift through hours of footage, finding the best takes, the perfect reactions, the moments that feel most authentic. The editing creates rhythm and pacing that might not have been apparent during shooting. It’s where the loose feeling of improvisation meets the precision of careful construction.

What this method achieves is dialogue that sounds like how people actually talk. There are overlaps, pauses, incomplete thoughts, verbal tics. People interrupt each other. They search for words. They go off on tangents. It feels real in a way that scripted dialogue, however well-written, rarely does.

But the method also creates specific challenges. Not every actor can work this way. It requires confidence, strong character work, and the ability to listen and respond rather than just waiting to deliver your next funny line. It requires ego sublimation—you might come up with something brilliant that gets cut because it doesn’t serve the scene or the story.

Guest’s genius is in making this incredibly difficult process look effortless. His films feel loose and spontaneous, but they’re actually carefully crafted. The structure is solid, the character work is deep, and the editing is precise. The improvisation serves the vision rather than replacing it.

The Visual Language: Documentary Realism

Guest’s visual approach is inseparable from his mockumentary format. His films look like actual documentaries, but that simplicity is deceptive. The camera placement, lighting, and editing all serve specific purposes.

The camera work in Guest’s films is deliberately unshowy. There are no elaborate tracking shots or crane moves. The camera observes from what feels like a natural position—sometimes slightly too far away, sometimes at an odd angle, sometimes struggling to keep up with the action. This creates the impression of a documentary crew trying to capture reality rather than a film crew staging scenes.

The lighting is naturalistic. Guest’s films are lit to look like available light—office fluorescents, home lamps, venue work lights. There’s no dramatic shadowing or mood lighting. This reinforces the documentary feel and keeps the focus on the performances.

Guest also uses the language of documentary filmmaking—talking head interviews, observational footage, the occasional shot of the camera crew being acknowledged or briefly seen in mirrors. These techniques create the framework within which the comedy operates.

But within this realistic framework, Guest is making careful artistic choices. The composition is always clear, ensuring we see what we need to see. The editing finds the perfect rhythm for each scene. The sound design captures not just dialogue but environmental details that add texture and authenticity.

Watch how Guest uses reaction shots. Often, the funniest moment in a scene is someone’s reaction to something absurd. The camera lingers on these reactions, allowing us to see the character processing what they’ve heard or seen. This requires the actors to stay in character even when they’re not speaking, and it creates layers of comedy beyond just the dialogue.

The interview sequences are particularly well-executed. Guest understands how people present themselves when they know they’re being filmed. There’s a performative quality, a slight formality, even when people are trying to appear casual. His characters sit just a bit too stiffly, look just slightly off-camera (at the interviewer), and present their stories as they want them to be understood rather than as they might actually be.

Guest also knows when to break from strict documentary realism. The performance sequences in his films—the actual show in “Guffman,” the dog show in “Best in Show,” the concert in “A Mighty Wind”—are shot more conventionally, with better production values. This makes sense within the logic of the films (the documentary crew has access to professional footage of these events) but it also serves an important function. After watching these characters struggle and prepare, we finally get to see them do the thing they’ve been working toward. The shift in visual style gives these moments weight and importance.

The Themes: Delusion, Dignity, and the Amateur Spirit

Guest’s films return again and again to certain themes, and understanding these recurring obsessions illuminates what makes his work so resonant.

First, there’s the theme of delusion—the gap between how we see ourselves and how others see us. Nearly every character in a Guest film is operating under some misapprehension about their own abilities or importance. Corky St. Clair believes he’s a professional theatrical director. Buck Laughlin thinks he’s a knowledgeable commentator. Mitch believes he can recapture past glory.

But Guest treats this delusion with compassion. He understands that self-belief, even when misplaced, is what allows people to create, perform, and put themselves out there. Without some degree of delusion, most of us would never attempt anything. The characters’ overestimation of their abilities is laughable, but it’s also touching. They’re trying. They’re putting themselves on the line. That takes courage, however misguided.

Related to this is the theme of dignity in the face of mediocrity. Guest’s characters aren’t particularly talented. Their productions are amateurish. Their performances are flawed. But they maintain their dignity, treating what they’re doing with seriousness and commitment. Guest honors this, even as he invites us to laugh at the results.

There’s also a persistent examination of the amateur versus the professional. Guest’s characters are typically amateurs operating in worlds that have professional standards. Community theater competing with Broadway. Dog owners competing at Westminster. Folk revival musicians remembering when they almost made it big. This amateur spirit—the willingness to commit to something without guarantee of success or recognition—is something Guest clearly finds both absurd and admirable.

The films also explore community and belonging. His characters find identity and meaning through their participation in these subcultures—community theater, dog showing, folk music. These communities have their own rules, hierarchies, and values. They provide structure and purpose. Guest understands the human need to be part of something, to have a role to play, to matter within some context.

Finally, there’s the theme of obsolescence and the passage of time. This is most explicit in “A Mighty Wind,” but it runs through all the films. Guest’s characters are often people whose moment has passed or never came. They’re holding onto past glory, pursuing outdated dreams, or operating in worlds the broader culture has moved beyond. There’s melancholy in this, a recognition that time moves forward while we cling to what was or what might have been.

These themes give Guest’s comedies unusual depth. We’re not just laughing at funny characters in silly situations. We’re engaging with ideas about identity, meaning, dignity, and mortality. The comedy is the entry point, but Guest offers something more substantial for those willing to engage with it.

The Legacy: Influence and Imitators

Guest’s influence on contemporary comedy is both obvious and underappreciated. The mockumentary format he perfected has been widely imitated, but few imitators capture what made his films work.

“The Office” (both UK and US versions) owes an enormous debt to Guest. The format, the improvisational feel, the observational humor, the careful character work—all of it builds on what Guest established. “Parks and Recreation,” “Modern Family,” “What We Do in the Shadows,” and countless other mockumentary-style shows follow the template Guest perfected.

Filmmakers like Jake Kasdan (“Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story”), the Lonely Island guys (“Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping”), and Larry Charles (“Borat”) have all worked in the mockumentary format with varying degrees of success. What many of them miss is Guest’s fundamental compassion for his characters and his refusal to chase easy laughs at their expense.

Guest’s improvisational approach has also influenced comedy more broadly. The idea that performers can create something organic and spontaneous within a structured framework is now common in comedy production. Directors regularly allow actors to improvise around scripted dialogue, keeping takes that capture spontaneous moments.

But perhaps Guest’s most important legacy is demonstrating that comedy can be sophisticated, character-driven, and formally rigorous while still being genuinely funny. His films aren’t sketch comedy expanded to feature length. They’re actual films with structure, themes, and carefully developed narratives. They respect their audience’s intelligence, trusting us to pick up on small details and observe for ourselves rather than having everything explained.

Guest proved that you could make films for relatively modest budgets, without major stars (though his ensemble is full of brilliant performers), that would find their audience and endure. His films have become comfort viewing for many people, movies that can be revisited endlessly because there’s always another layer to discover, another background detail to catch, another line reading to appreciate.

The Later Works and Evolution

Guest continued working after “A Mighty Wind,” though less prolifically. “For Your Consideration” (2006) examined the film industry’s awards season obsession, following a cast and crew whose low-budget film generates unexpected Oscar buzz. The film featured Guest’s usual ensemble and maintained his approach, but it was his first to largely abandon the mockumentary format in favor of a more traditional narrative structure.

“For Your Consideration” is an underrated entry in Guest’s filmography. It’s not quite as tightly constructed as his best work, and the abandonment of the documentary framing removes some of the distinctive texture of his earlier films. But it contains brilliant moments and performances, particularly O’Hara as an actress whose entire sense of self becomes wrapped up in awards consideration.

The film’s examination of how awards buzz can warp perspective and create delusion fits perfectly within Guest’s thematic concerns. The characters who briefly believe they might win Oscars are engaging in the same kind of hopeful delusion as Corky St. Clair waiting for Guffman or Mitch believing he can recapture his folk music glory.

After “For Your Consideration,” Guest stepped back from directing, though he’s continued acting and other creative work. This hiatus makes the body of work feel even more special—four nearly perfect mockumentaries, plus “For Your Consideration” and his contributions to “Spinal Tap.” It’s a relatively small filmography, but its impact has been disproportionately large.

Why Guest’s Films Endure

In an era of increasingly broad, desperate comedy, where films seem to exhaust every joke and explain every gag, Guest’s work feels more valuable than ever. His films trust the audience. They operate through observation and accumulation rather than forced punchlines. They build characters so richly that we could probably watch them do anything and find it interesting.

The films also reward close attention. There are always background details, throwaway lines, subtle reactions that you might miss on first viewing. This makes them infinitely rewatchable. Every time you return to “Best in Show” or “Waiting for Guffman,” you notice something new.

Guest’s work also benefits from its fundamental kindness. Yes, we’re laughing at these characters, but we’re also rooting for them. We want Corky’s show to succeed. We care about whether Mitch and Mickey will kiss. We’re invested in the Flecks and their Weimaraner. Guest has created comedy that’s funny precisely because it recognizes the humanity in absurdity.

There’s also something deeply democratic about Guest’s approach. He’s not interested in exceptional people or extraordinary circumstances. He’s interested in ordinary people doing ordinary things with extraordinary commitment. His films suggest that everyone has a story worth telling, that every subculture has its own logic and appeal, that dignity isn’t reserved for high art or important people.

This democratization extends to the filmmaking itself. Guest’s methods demonstrate that you don’t need massive budgets, elaborate effects, or conventional star power to make something memorable. You need good ideas, talented collaborators, and a clear vision. This has inspired countless filmmakers working on limited resources.

Personal Reflections from a Devoted Fan

For those of us who count ourselves among Guest’s devotees, the films occupy a special place in our cinematic landscape. They’re not movies we watch once and move on from. They’re films we return to again and again, like visiting old friends.

Part of what makes Guest’s work so rewarding for repeat viewing is that it operates on multiple levels. On first watch, you’re caught up in the stories and the big laughs. On subsequent viewings, you start noticing the craft—the perfect edit, the character detail established in a single shot, the way a subplot pays off in exactly the right way.

There’s also the pleasure of getting to know the characters so well that they feel real. I know Corky St. Clair’s mannerisms, Cookie Fleck’s vocal patterns, Buck Laughlin’s particular brand of obliviousness. These characters exist in my mind as fully-formed people, not just as comedic constructs.

Guest’s films also provide a masterclass in comedy craft for anyone interested in understanding how humor works. Watch how he builds comedy through accumulation, how he uses specificity to make absurdity believable, how he creates comic rhythm through editing. These are lessons that apply far beyond mockumentary filmmaking.

For many of us, Guest’s films have become comfort viewing—movies we put on when we need something familiar and reliably enjoyable. There’s something soothing about their rhythms, their gentle humor, their fundamental humanity. In a world that often feels harsh and divisive, Guest’s films remind us that people are absurd and wonderful, that our strange obsessions and modest dreams matter, that there’s dignity in trying even when success is unlikely.

The Ensemble as Collaborative Art

One aspect of Guest’s work that deserves more recognition is how thoroughly collaborative it is. While Guest is the director and driving vision, his films are ensemble pieces in the truest sense. Every performer contributes to the final product, bringing their own creativity and choices to bear.

This collaborative spirit extends beyond the performances. Guest works with the same key crew members across multiple films—costume designer Julie Asher, editor Robert Leighton, composers Michael McKean and Harry Shearer, production designer Joseph T. Garrity. These long-term collaborations create a shared vocabulary and understanding that elevates the work.

The costume design in Guest’s films, for instance, is brilliantly specific. Every character’s wardrobe tells a story about who they are, what they value, how they want to be perceived. Corky’s vests in “Guffman,” the Flecks’ mismatched outfits in “Best in Show,” the period-appropriate costumes in “A Mighty Wind”—all of it contributes to character and comedy without drawing undue attention to itself.

The music in Guest’s films (when it’s featured) is legitimately good. The songs in “A Mighty Wind” work as both parody and actual folk music. The “Red, White and Blaine” numbers in “Guffman” capture the particular flavor of community theater earnestness. This commitment to quality in every element of the production creates a world that feels real and lived-in.

The Unspoken Influences and Cinematic Lineage

While Guest’s work is distinctive, it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. We can trace influences from cinema verité and direct cinema, from the observational documentaries of Frederick Wiseman, from the character-based sketch comedy of Second City and SCTV (where several Guest regulars worked).

There’s also something of the British comedy tradition in Guest’s work—the Ealing comedies, the films of Mike Leigh, the television work of Alan Bennett. Like these British artists, Guest finds humor in everyday life, in the gap between aspiration and reality, in the particular ways people deceive themselves and others.

The mockumentary format itself has roots in earlier works like “A Hard Day’s Night” and “David Holzman’s Diary,” but Guest and his collaborators transformed it into something more sophisticated and sustainable. They proved it wasn’t just a one-off gimmick but a legitimate approach to comedy filmmaking.

The Importance of Context: Small Stories in a Big World

Guest’s films are also notable for what they don’t include. There are no explosions, no car chases, no world-ending stakes. The conflicts are small—will Guffman show up? Who will win Best in Show? Will the memorial concert go well? In a cinematic landscape increasingly dominated by superhero movies and franchise spectacles, Guest’s commitment to small, human stories feels almost radical.

But these small stories resonate because they’re universal. We may not all show dogs or perform in community theater, but we all know what it’s like to want recognition, to invest ourselves in something that others might find trivial, to hope for a moment when we’ll be seen and appreciated.

Guest understands that most of life happens at this scale—not in world-saving heroics but in the everyday pursuit of meaning and connection. His films validate these small pursuits, suggesting they’re worthy of our attention and sympathy.

Final Reflections: The Master’s Legacy

Christopher Guest has created a body of work that stands apart from mainstream Hollywood comedy. His films are smarter, more observant, more carefully crafted than most. They’re also deeply humane, finding comedy in human folly without becoming cruel or dismissive.

For those of us who love the mockumentary genre, Guest represents its pinnacle. He didn’t just make mockumentaries; he made the mockumentaries, the films that define what the form can be at its best. Every other work in the genre is inevitably measured against “Waiting for Guffman,” “Best in Show,” and “A Mighty Wind.”

But Guest’s influence extends beyond format. He’s shown us that comedy can be sophisticated and popular, that improvisation can serve careful construction, that ordinary people doing ordinary things can be endlessly fascinating. He’s created indelible characters, unforgettable moments, and films that reward endless rewatching.

In an era when so much comedy feels disposable, created for quick consumption and instant forgetting, Guest’s films feel permanent. They’re movies that will be watched and studied and loved for decades to come. They’ve already influenced a generation of comedians and filmmakers. They’ll continue to influence future generations.

For cinephiles who appreciate craft, who value character over plot, who find beauty in careful observation and perfect execution, Christopher Guest’s work represents a treasure. These films are masterpieces of their kind, created by an artist with singular vision and the talent to realize it. They make us laugh, certainly, but they also make us think, feel, and see the world a bit differently.

That’s the mark of great art, regardless of genre or ambition. Christopher Guest has given us great art, disguised as mockumentaries about dog shows and community theater. Those of us who recognize what he’s accomplished are grateful for every frame, every performance, every perfectly-timed cut. These films are gifts, and they’ll endure because they’re made with care, intelligence, and genuine affection for the human comedy in all its absurd glory.

Long may they be watched, quoted, and cherished by those of us who understand that true artistry can be found anywhere—even in a small Missouri town waiting for a theatrical agent named Guffman who will never arrive.

From start to finish, this blog post had us hooked. The content was insightful, entertaining, and had us feeling grateful for all the amazing resources out there. Keep up the great work!

Thank you so much,

really appreciated!

Your words have the power to change lives and I am grateful for the positive impact you have had on mine Thank you

I love how your posts are both informative and entertaining You have a talent for making even the most mundane topics interesting

It’s always a joy to stumble upon content that genuinely makes an impact and leaves you feeling inspired. Keep up the great work!