Fritz Lang, an Austrian-German-American filmmaker, stands as one of the towering figures in the history of cinema. His career, spanning nearly four decades and multiple continents, produced a body of work that not only captivated audiences but also redefined the possibilities of the medium. From the silent masterpieces of the Weimar era to the gritty noirs of Hollywood, Lang’s films are marked by their technical precision, thematic depth, and an unflinching exploration of human nature. This article delves into Lang’s life, his most successful films, his distinctive style, and the enduring legacy that continues to influence filmmakers today.

Early Life and Beginnings

Friedrich Christian Anton Lang was born on December 5, 1890, in Vienna, Austria, to a middle-class family. His father, Anton, was an architect, and his mother, Pauline, was of Jewish descent, though she converted to Catholicism before Lang’s birth. Raised in a culturally vibrant city, Lang developed an early interest in art, architecture, and literature. He briefly studied architecture at the Technical University of Vienna but soon gravitated toward painting and travel, spending time in Asia and North Africa. These experiences broadened his worldview, infusing his later work with a cosmopolitan sensibility.

World War I marked a turning point for Lang. He enlisted in the Austrian army in 1914, serving as an officer until he was wounded and discharged in 1916. During his recovery, he began writing scripts for films, a medium that was gaining prominence. By 1917, Lang had moved to Berlin, the epicenter of German cinema, and started working as a writer and actor before transitioning to directing. His early exposure to Expressionism, a German art movement emphasizing emotional intensity and distorted reality, profoundly shaped his cinematic vision.

The Weimar Years: Silent Masterpieces

Lang’s rise to prominence coincided with the golden age of German cinema during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933). Working primarily at UFA (Universum Film AG), Germany’s leading film studio, he crafted films that blended technical innovation with philosophical inquiry. His Weimar-era films remain some of the most celebrated in cinema history.

Metropolis (1927)

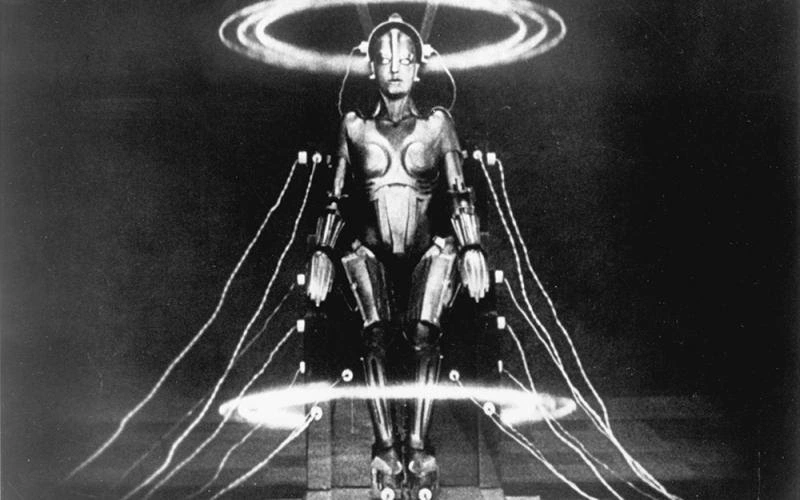

Metropolis, Lang’s most ambitious silent film, is a landmark of science fiction and German Expressionism. Set in a dystopian future, the film depicts a divided society where the wealthy elite live in luxury above ground, while workers toil in oppressive conditions below. The story follows Freder, a privileged young man, who falls in love with Maria, a worker advocating for unity. With its groundbreaking special effects, including the iconic transformation of the robot Maria, Metropolis was a visual marvel.

The film’s production was famously arduous, costing an estimated five million Reichsmarks (equivalent to roughly $200 million today, adjusted for inflation). Lang’s perfectionism led to elaborate sets, thousands of extras, and innovative techniques like the Schüfftan process, which used mirrors to create the illusion of vast cityscapes. Upon release, Metropolis received mixed reviews; critics admired its spectacle but found its narrative simplistic. Over time, however, it has been recognized as a visionary work, influencing films like Blade Runner (1982) and The Matrix (1999).

Thematically, Metropolis explores class struggle, technology’s dual nature, and the quest for human connection—recurring motifs in Lang’s oeuvre. Its restored versions, particularly the 2010 cut incorporating rediscovered footage, have cemented its status as a cultural touchstone.

M (1931)

Lang’s first sound film, M, is often cited as his masterpiece and one of the greatest films ever made. Starring Peter Lorre as Hans Beckert, a child murderer terrorizing Berlin, M is a chilling psychological thriller that examines morality, justice, and societal paranoia. The film’s narrative alternates between Beckert’s crimes, the police manhunt, and the criminal underworld’s parallel efforts to capture him.

M showcases Lang’s mastery of sound as a narrative tool. In an era when many filmmakers treated sound as an afterthought, Lang used it deliberately—most famously in Beckert’s whistled refrain of “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” which signals his presence without visuals. The film’s cinematography, with its stark contrasts and claustrophobic framing, reflects the influence of Expressionism while anticipating film noir.

Thematically, M is a complex meditation on guilt and punishment. Lang avoids sensationalizing Beckert’s crimes, instead portraying him as a tormented figure, driven by compulsion yet aware of his monstrosity. The film’s climax, a mock trial conducted by criminals, raises provocative questions about justice: Is society’s response to evil any less barbaric than the crimes themselves? M was a critical and commercial success, launching Lorre to stardom and solidifying Lang’s reputation as a cinematic innovator.

Other Weimar Highlights

Before Metropolis and M, Lang directed several notable films, including Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), a two-part crime epic about a master criminal manipulating society through hypnosis and deceit. The character of Dr. Mabuse, a symbol of chaos and control, reappeared in later Lang films, reflecting his fascination with power dynamics. Die Nibelungen (1924), a two-part adaptation of Germanic mythology, showcased Lang’s ability to blend spectacle with psychological depth, while Spies (1928) anticipated the espionage genre with its tale of intrigue and betrayal.

These films established Lang as a leading figure in German cinema, but the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933 forced a dramatic shift in his career.

Exile and Hollywood: Reinvention in America

In 1933, as Hitler consolidated power, Lang, whose mother was of Jewish descent, faced increasing peril. According to a famous (though possibly apocryphal) anecdote, Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, offered Lang a position overseeing German film production. Lang, appalled by the regime, fled to Paris that night, leaving behind his wife and collaborator, Thea von Harbou, who joined the Nazi Party. After a brief stint in France, where he directed Liliom (1934), Lang arrived in Hollywood in 1934, signing with MGM.

Adapting to the American studio system was challenging for Lang, who was accustomed to creative control. Hollywood’s commercial demands clashed with his meticulous approach, yet he carved out a distinctive niche, particularly in the genres of crime drama and film noir.

Fury (1936)

Lang’s American debut, Fury, starring Spencer Tracy, marked a powerful entry into Hollywood. The film follows Joe Wilson, an innocent man wrongly accused of kidnapping, who narrowly escapes a lynch mob only to seek vengeance against his attackers. Fury blends social commentary with psychological intensity, critiquing mob mentality and the fragility of justice—themes resonant with Lang’s experiences in Weimar Germany.

Critics praised Fury for its gripping narrative and Tracy’s performance, though some felt Lang’s European sensibilities made the film overly grim for American audiences. Nonetheless, it established Lang as a director capable of tackling American stories with universal resonance.

You Only Live Once (1937)

Lang’s follow-up, You Only Live Once, starring Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sidney, is considered one of the earliest examples of film noir. The story of a wrongly convicted ex-convict and his loyal wife, the film explores fate, societal prejudice, and doomed love. Its fatalistic tone, shadowy visuals, and morally ambiguous characters set a template for noir classics like Double Indemnity (1944).

The Big Heat (1953)

Among Lang’s later Hollywood works, The Big Heat stands out as a quintessential noir. Glenn Ford stars as Dave Bannion, a detective whose crusade against a crime syndicate leads to personal tragedy. The film’s raw violence—most notoriously a scene where Lee Marvin’s character throws scalding coffee in Gloria Grahame’s face—shocked audiences, while its portrayal of corruption and moral compromise reflected the cynicism of post-war America.

The Big Heat was a critical and commercial hit, showcasing Lang’s ability to balance genre conventions with social critique. Its influence is evident in later crime films, from Chinatown (1974) to L.A. Confidential (1997).

Other Hollywood Works

Lang’s Hollywood career included diverse films like Man Hunt (1941), an anti-Nazi thriller, and Scarlet Street (1945), a bleak noir about obsession and betrayal. Woman in the Moon (1929), though made in Germany, prefigured his later Hollywood sci-fi thriller The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). While not all his American films achieved the acclaim of his Weimar output, they consistently bore his signature: taut storytelling, moral complexity, and visual sophistication.

Lang’s Style: A Cinematic Architect

Lang’s filmmaking style is often described as architectural, reflecting his early training and meticulous attention to detail. His films are visually striking, with compositions that guide the viewer’s eye and convey narrative subtext. Below are key elements of his style:

Visual Precision and Expressionism

Lang’s Weimar films, steeped in German Expressionism, feature exaggerated sets, dramatic lighting, and distorted perspectives to evoke psychological states. Metropolis’s towering cityscapes and M’s shadowy alleys create worlds that feel both real and surreal. Even in Hollywood, where realism was favored, Lang retained a stylized approach—seen in the stark contrasts of The Big Heat or the claustrophobic framing of Scarlet Street.

Mastery of Sound

In M, Lang pioneered the use of sound as a narrative device, from Beckert’s whistle to the absence of music during tense scenes, heightening suspense. In his Hollywood films, he used dialogue and ambient sounds to underscore emotional undercurrents, as in the cacophony of the lynch mob in Fury.

Themes of Fate and Morality

Lang’s films often explore humanity’s struggle against fate, whether societal (class divisions in Metropolis), psychological (Beckert’s compulsions in M), or systemic (corruption in The Big Heat). His protagonists are rarely heroes; they are flawed, caught in moral dilemmas that reflect broader human conflicts.

Technical Innovation

Lang was a technical trailblazer. Metropolis introduced effects that became industry standards, while M’s use of leitmotifs anticipated modern sound design. In Hollywood, he adapted to new technologies, like deep-focus photography in You Only Live Once, to enhance storytelling.

Pessimism and Social Critique

Lang’s worldview, shaped by war and exile, imbued his films with a skeptical view of authority and human nature. Whether depicting Weimar Germany’s chaos or America’s underbelly, he exposed societal flaws—corruption, mob rule, and the dehumanizing effects of modernity—while avoiding didacticism.

Later Years and Return to Germany

By the 1950s, Lang’s relationship with Hollywood soured due to studio interference and the blacklist era’s paranoia, which targeted many European émigrés. Frustrated, he returned to Germany in 1957, directing The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb (1959), a two-part adventure inspired by his earlier scripts. His final film, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), revisited his iconic villain, updating the character for the Cold War era.

Lang retired from filmmaking in 1960, citing failing eyesight and exhaustion. He spent his later years lecturing, mentoring young filmmakers, and reflecting on his career. He died on August 2, 1976, in Beverly Hills, leaving behind a legacy that transcended borders.

Legacy and Influence

Fritz Lang’s impact on cinema is immeasurable. His films shaped genres, inspired auteurs, and continue to resonate with audiences. Below are key aspects of his legacy:

Genre Pioneer

Lang’s work laid the groundwork for science fiction (Metropolis), psychological thrillers (M), and film noir (The Big Heat). His fusion of genre storytelling with philosophical depth influenced directors like Alfred Hitchcock, who admired M’s suspense, and Ridley Scott, whose Blade Runner echoes Metropolis’s dystopian vision.

Influence on Auteurs

Lang’s stylistic and thematic innovations inspired the French New Wave, particularly Jean-Luc Godard, who referenced Lang in Contempt (1963). Martin Scorsese, David Fincher, and Christopher Nolan have cited Lang’s meticulous framing and moral ambiguity as influences. Fincher’s Se7en (1995), with its grim urban setting and tormented villain, feels like a direct descendant of M.

Technical and Cultural Impact

Lang’s technical contributions—special effects, sound design, and narrative structure—set standards still in use. Metropolis’s imagery has permeated popular culture, from music videos (Madonna’s “Express Yourself”) to comics (Superman’s Metropolis). M’s exploration of criminal psychology prefigured true-crime narratives and procedural dramas.

Preservation and Rediscovery

Efforts to restore Lang’s films, particularly Metropolis, have ensured their accessibility to new generations. The 2010 restoration, incorporating footage found in Argentina, revealed the film’s full scope, while M’s crisp prints highlight its timeless power. Film archives and festivals, like the Berlin International Film Festival, continue to celebrate Lang’s work.

Philosophical Resonance

Lang’s films remain relevant for their exploration of timeless questions: How does society balance justice and vengeance? Can technology uplift or destroy humanity? His refusal to provide easy answers invites viewers to grapple with these issues, making his work as urgent today as it was decades ago.

Conclusion

Fritz Lang was more than a filmmaker; he was a visionary who saw cinema as a canvas for exploring the human condition. From the futuristic spectacle of Metropolis to the raw intensity of M and the hard-boiled cynicism of The Big Heat, his films reflect a singular mind grappling with the complexities of modernity. His style—precise, evocative, and unflinchingly honest—set a standard for cinematic storytelling, while his themes of fate, morality, and societal decay continue to echo in contemporary cinema.

Lang’s journey, from Vienna to Berlin to Hollywood and back, mirrors the upheavals of the 20th century. Yet his work transcends its historical context, speaking to universal truths about power, guilt, and redemption. As long as filmmakers seek to probe the depths of human experience, Fritz Lang’s legacy will endure, a beacon for those who believe cinema can change the way we see the world.