In the pantheon of world cinema, few figures loom as large as Federico Fellini. Born in the small coastal town of Rimini, Italy, on January 20, 1920, Fellini would rise to become not just one of Italy’s most celebrated filmmakers but a transformative force in global cinema whose influence continues to reverberate decades after his death. His name has transcended mere identification to become an adjective—”Felliniesque”—a term that evokes the fantastical, the carnivalesque, the simultaneously grotesque and beautiful, the blending of memory and imagination that characterized his distinctive cinematic vision.

Across a career spanning more than four decades, Fellini created a body of work that defied easy categorization, moving from the neorealist traditions of postwar Italian cinema to increasingly personal, dreamlike explorations of memory, desire, celebrity, and the creative process itself. His films—among them such masterpieces as La Strada, La Dolce Vita, 8½, and Amarcord—expanded the language of cinema, challenging conventional narrative structures and embracing a visual style that was at once baroque and deeply humanistic.

This article aims to explore the life and work of Federico Fellini, tracing his evolution as an artist, examining the distinctive elements of his filmmaking style, and assessing his enduring impact on cinema and popular culture. Through this exploration, we will come to understand not just the achievements of a singular filmmaker but also gain insight into the power of cinema as an art form capable of transforming our understanding of reality itself.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Childhood in Rimini

Federico Fellini’s childhood in Rimini would later serve as an inexhaustible wellspring of imagery and themes throughout his filmmaking career. Born to middle-class parents—his father Urbano was a traveling salesman and his mother Ida a housewife—young Federico found escape and inspiration in the provincial coastal town’s movie theater, the Fulgor Cinema. Here, amid the flickering images projected on the screen, particularly American films starring Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and the comedic duo Laurel and Hardy, Fellini’s imagination took flight.

The Rimini of Fellini’s youth was a place of stark contrasts: the traditional Catholic values espoused by his education with the Salesians, the allure of the seaside Grand Hotel frequented by wealthy tourists, and the carnivalesque atmosphere of traveling circuses that periodically visited the town. These elements—religion, luxury, spectacle—would later become recurrent motifs in his films, transformed through the alchemical process of his artistic vision.

Equally influential was the rise of fascism during his formative years. Mussolini’s regime, with its bombastic propaganda and cult of personality, provided Fellini with an early education in the power of images and spectacle to shape perception—a lesson he would later apply to his own works, albeit with radically different aims.

Early Career as a Caricaturist and Journalist

Before Fellini ever stepped behind a camera, he was developing his visual acuity and narrative sensibilities through other mediums. At the age of seventeen, he moved to Florence where he worked briefly as a proofreader for the newspaper La Nazione. Soon after, he relocated to Rome, where his career began in earnest.

In Rome, Fellini found work as a cartoonist and writer for the humor magazine Marc’Aurelio, where his caricatures and satirical vignettes displayed an early talent for capturing human peculiarities with a blend of affection and irreverence. This period proved crucial to his development as an artist, as he honed his observational skills and developed the ability to distill complex personalities into distinctive visual characteristics—a talent that would later inform his casting choices and character designs in film.

Additionally, Fellini wrote for radio programs, most notably “Cico and Pallina,” a comedy series starring his future wife, Giulietta Masina. This work in radio comedy taught him the rhythms of dialogue and the importance of sound in storytelling, elements that would later distinguish his films even as they became increasingly visual and dreamlike.

Encounter with Neorealism and Roberto Rossellini

The pivotal moment in Fellini’s transition to filmmaking came through his collaboration with Roberto Rossellini, one of the founding figures of Italian neorealism. During World War II, Fellini had managed to avoid military service through his employment at the Allied-controlled Radio Roma, where he met Rossellini. This encounter would change the trajectory of his career.

Rossellini, impressed by Fellini’s talents, invited him to collaborate as a screenwriter on Rome, Open City (1945), a landmark of neorealist cinema that depicted the Nazi occupation of Rome with unprecedented rawness and immediacy. Fellini continued this collaboration on Rossellini’s Paisan (1946), further immersing himself in the neorealist aesthetic that emphasized location shooting, non-professional actors, and stories of ordinary people struggling against social and economic forces beyond their control.

While Fellini would eventually move beyond strict neorealism, this apprenticeship under Rossellini instilled in him an appreciation for authenticity and a commitment to capturing the texture of real life—elements that remained even as his films became more stylized and fantastical. The tension between realism and fantasy, documentary and dream, would become one of the defining characteristics of Fellini’s mature work.

The Evolution of a Filmmaker

Early Directorial Works and the Transition from Neorealism

Fellini’s directorial debut came in 1950 with Variety Lights (Luci del varietà), co-directed with Alberto Lattuada. This film, which follows a traveling vaudeville troupe, already contained elements that would become Fellini signatures: a fascination with performers, an episodic narrative structure, and a blend of the comic and melancholic. While still operating within the neorealist framework, Variety Lights hinted at Fellini’s eventual departure from its strict conventions.

His solo directorial debut, The White Sheik (Lo sceicco bianco, 1952), further developed these tendencies. The film, a satire about a provincial newlywed who abandons her husband to pursue her idol, a photoromanzo actor, explored the gap between fantasy and reality that would become a central theme in Fellini’s oeuvre. Though not initially successful, the film displayed Fellini’s growing confidence as a visual storyteller.

I Vitelloni (1953) marked Fellini’s first significant critical success. This semi-autobiographical portrait of five young men drifting aimlessly in a provincial seaside town drew on Fellini’s memories of Rimini and established his talent for blending social observation with personal memory. The film’s influence can be traced through numerous coming-of-age stories in world cinema, from Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets to George Lucas’s American Graffiti.

International Recognition: La Strada and Beyond

It was with La Strada (1954) that Fellini achieved international acclaim. This poetic fable about a simple-minded young woman (Giulietta Masina) sold to a brutal strongman (Anthony Quinn) who travels from town to town performing feats of strength combined neorealist settings with an allegorical dimension that transcended the movement’s social determinism. The film won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and established Fellini as a major voice in world cinema.

La Strada also marked the beginning of Fellini’s collaboration with composer Nino Rota, whose haunting, circus-like melodies became inextricably linked with Fellini’s visual imagination. Similarly, Masina’s performance—combining the physical comedy of Chaplin with an almost transcendent innocence—established her as Fellini’s muse and one of cinema’s most unforgettable presences.

Following La Strada, Fellini continued to expand his artistic range with films like Il Bidone (1955), a darker exploration of con artists that further developed his interest in performers and deception, and Nights of Cabiria (Le notti di Cabiria, 1957), which earned him a second Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The latter, starring Masina as a resilient Roman prostitute who maintains her optimism despite repeated betrayals, showcased Fellini’s deepening humanism and his ability to find beauty and dignity in marginalized lives.

The Watershed: La Dolce Vita and the Turn Toward Expressionism

If Fellini’s early films represented a gradual loosening of neorealist constraints, La Dolce Vita (1960) marked a decisive break. This episodic portrait of a jaded journalist (Marcello Mastroianni) moving through the decadent high society of postwar Rome abandoned neorealism’s focus on the working class to examine the spiritual emptiness beneath the glittering surface of economic prosperity.

Visually, La Dolce Vita was Fellini’s most ambitious work to date, with iconic sequences such as Anita Ekberg’s moonlit swim in the Trevi Fountain and the film’s opening shot of a helicopter transporting a statue of Christ over Rome. These images, at once spectacular and symbolically resonant, announced Fellini’s evolving style toward the more expressionistic and dreamlike compositions that would characterize his later works.

The film provoked intense controversy in Italy, where it was condemned by the Catholic Church for its frank portrayal of hedonism and spiritual malaise. Nevertheless, it was a commercial triumph internationally and won the Palme d’Or at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival. More significantly, it introduced the term “paparazzi” into the global lexicon (named after the character Paparazzo in the film) and captured a pivotal moment in Italian society’s transition toward consumerism and media saturation.

Creative Crisis and Triumph: 8½ and the Autobiographical Turn

Following the success of La Dolce Vita, Fellini faced a creative crisis that would result in his most acclaimed masterpiece. Struggling with what would be his next project, he turned his personal artistic block into the subject of the film itself. The result was 8½ (1963), named for the fact that it represented Fellini’s eighth and a half directorial effort (counting his previous seven features, two short segments, and his co-direction of Variety Lights as a “half” film).

8½ follows film director Guido Anselmi (Mastroianni, now firmly established as Fellini’s on-screen alter ego) as he attempts to mount a science fiction film while besieged by creative doubts, memories, fantasies, and the demands of producers, crew members, mistresses, and his estranged wife. The film’s revolutionary structure—seamlessly blending reality, memory, and dream—created a new grammar for representing subjective experience in cinema.

Beyond its formal innovations, 8½ offered a profound meditation on the creative process itself, exploring the tension between an artist’s life experiences and their transformation into art. The film’s conclusion, in which Guido abandons his pretensions to intellectual profundity and embraces a carnivalesque celebration of life in all its contradictions, reflected Fellini’s own artistic philosophy.

8½ won Fellini his third Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made. Its influence extends beyond cinema into literature, music, theater, and even fashion, with Guido’s sunglasses and suit becoming an iconic image of directorial cool.

The Felliniesque Style: Key Elements and Recurring Themes

Visual Extravagance and the Baroque Imagination

Perhaps the most immediately recognizable aspect of Fellini’s mature style is its visual extravagance. Beginning with La Dolce Vita and reaching its apotheosis in films like Juliet of the Spirits (Giulietta degli spiriti, 1965), Fellini Satyricon (1969), and Roma (1972), Fellini developed an increasingly baroque visual language characterized by elaborate set designs, flamboyant costumes, exaggerated makeup, and carefully choreographed crowd scenes.

This visual excess was not mere indulgence but a deliberate aesthetic strategy that reflected Fellini’s belief in cinema as a medium of dreams rather than strict realism. “All art is autobiographical,” Fellini once remarked. “The pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.” In this metaphor, the pearl’s lustrous surface—the stylization of experience—becomes as important as the grain of sand—the lived experience—that initiated its formation.

Central to Fellini’s visual style was his collaboration with cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno, whose lighting schemes emphasized the theatrical and artificial nature of the filmic world, and production designer Dante Ferretti, whose elaborate sets transformed Cinecittà studios into landscapes of memory and imagination. Together, they created a cinematic world instantly identifiable as “Felliniesque”—a world where exaggeration served emotional and psychological truth.

The Carnivalesque, Grotesque, and Celebration of Human Variety

Another hallmark of Fellini’s cinema is his embrace of the carnivalesque—the temporary suspension of social hierarchies and norms in favor of play, excess, and the celebration of the body in all its imperfect glory. Influenced by his childhood memories of circuses and traveling performers, Fellini populated his films with a gallery of physically distinctive individuals: dwarfs, giants, the obese, the emaciated, faces that might be described as grotesque by conventional standards but which Fellini presented with overwhelming affection.

This fascination with human variety reached its apex in Fellini’s Casanova (1976), where the director deliberately cast against type by having Donald Sutherland play the legendary lover as an emotional automaton in a world of mannered decadence, and in The Clowns (I clowns, 1970), a pseudo-documentary that explored the history and symbolism of circus clowns while serving as a metaphor for Fellini’s own artistic persona.

The carnivalesque in Fellini’s work serves multiple functions: it democratizes beauty by finding value in the conventionally unattractive; it challenges social pretensions by emphasizing the shared corporeality of all humans regardless of status; and it creates a space for freedom and authenticity in societies governed by rigid expectations. As Mikhail Bakhtin noted in his analysis of carnival in literature, the grotesque body “is a body in the act of becoming… never finished, never completed; it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body”—a perfect description of Fellini’s dynamic visual compositions.

Memory, Nostalgia, and the Mythologization of the Past

While Fellini’s films grew increasingly fantastical over time, they remained deeply rooted in his personal memories, particularly of his provincial childhood. Amarcord (1973), whose title derives from the Romagnol dialect phrase “a m’arcord” (“I remember”), represents the fullest expression of this tendency. Set in a coastal town clearly modeled on Rimini during the fascist era, the film reconstructs Fellini’s adolescence through a series of vignettes that blend historical reality with surreal exaggeration.

What distinguishes Fellini’s approach to memory is his recognition of its inherently unreliable and creative nature. Rather than attempting documentary accuracy, he embraced the ways in which memory transforms experience, magnifying some elements while diminishing others, creating a personal mythology that reveals emotional rather than literal truth. “The pearl is the oyster’s autobiography,” he remarked, suggesting that the embellishment of memory is not falsification but a form of truth-telling that penetrates deeper than mere facts.

This approach to memory extends to Fellini’s treatment of history itself. In films like Roma and Fellini Satyricon, he approached historical periods—contemporary Rome and ancient Rome, respectively—not as subjects for accurate reconstruction but as landscapes for exploring timeless human concerns: spirituality, sexuality, power, and the search for meaning. By mythologizing rather than documenting the past, Fellini created works that, paradoxically, feel both deeply personal and universally resonant.

The Catholic Imagination and Religious Symbolism

Despite his reputation as a chronicler of decadence and sensuality, Fellini’s films are suffused with religious imagery and concerns that reflect his Catholic upbringing. From the Christ statue flying over Rome in the opening of La Dolce Vita to the ecclesiastical fashion show in Roma, Catholicism provided Fellini with a rich symbolic vocabulary and a framework for exploring questions of guilt, transcendence, and spiritual longing.

Fellini’s relationship with religion was complex and ambivalent. While he maintained a lifelong fascination with Catholic ritual and symbolism, his films often satirized religious institutions and authorities. This tension—between spiritual yearning and skepticism toward organized religion—animates many of his greatest works, particularly La Dolce Vita, whose structure has been compared to Dante’s journey through the circles of hell, and 8½, which concludes with a redemptive vision that is simultaneously secular (a circus parade) and spiritual (a symbol of universal harmony).

Furthermore, Fellini’s interest in dreams, Jungian psychology, and various forms of mysticism (he regularly consulted with psychics and participated in séances) suggests a spiritual sensibility that transcended institutional Catholicism while remaining indebted to its emphasis on mystery, symbol, and the sacred dimension of existence. This syncretistic approach to spirituality allowed Fellini to create films that resonated with viewers across religious and cultural boundaries.

Gender, Sexuality, and the Female Figure

Women occupy a central but complicated position in Fellini’s cinematic universe. On one hand, his films feature some of cinema’s most memorable female characters, many played by his wife and muse Giulietta Masina, whose performances in La Strada, Nights of Cabiria, and Juliet of the Spirits combine vulnerability with indomitable resilience. On the other hand, Fellini has been criticized for his tendency to objectify female bodies and reduce women to archetypes reflecting male fantasies and fears: the innocent, the whore, the mother, the temptress.

This ambivalence is particularly evident in films like City of Women (La città delle donne, 1980), which presents itself as an exploration of feminism but ultimately reveals more about male anxiety in the face of changing gender roles than about women’s actual experiences. Similarly, the recurrent figure of the abundant-bodied woman in Fellini’s films—epitomized by Anita Ekberg in La Dolce Vita and various characters in Amarcord and 8½—can be interpreted either as a celebration of female sensuality liberated from restrictive standards or as a reduction of women to their physical attributes.

What saves Fellini from simple misogyny is the evident affection with which he portrays his female characters and his willingness to critique the masculine gaze, particularly in 8½, where Guido’s objectification of women is presented as a symptom of his spiritual and creative malaise. Additionally, films like Juliet of the Spirits attempt, however imperfectly, to enter female subjectivity and explore women’s struggles for autonomy in a patriarchal society.

Artistic Collaborations and Working Methods

The Fellini Repertory Company: Mastroianni, Masina, and Others

Like many great directors, Fellini frequently collaborated with a core group of actors who became integral to his cinematic vision. Most notable among these was Marcello Mastroianni, whose performances in La Dolce Vita, 8½, and City of Women established him as Fellini’s on-screen surrogate. Mastroianni’s ability to combine world-weary sophistication with childlike vulnerability made him the perfect vehicle for exploring Fellini’s complex attitude toward masculinity and creativity.

Equally important was Giulietta Masina, Fellini’s wife from 1943 until his death. Often compared to Charlie Chaplin for her expressive physical performances, Masina brought a unique combination of pathos and resilience to her roles in La Strada, Nights of Cabiria, and Juliet of the Spirits. Their personal and professional partnership, while not without tensions, produced some of cinema’s most enduring character portraits.

Beyond these central figures, Fellini developed ongoing collaborations with actors like Sandra Milo, who appeared in 8½ and Juliet of the Spirits; Anthony Quinn, who starred in La Strada; and Anita Ekberg, whose performance in La Dolce Vita created one of cinema’s most iconic images. In his later films, Fellini increasingly turned to non-professional actors chosen for their distinctive physical appearances, a practice that reflected his interest in physiognomy as an expression of inner character.

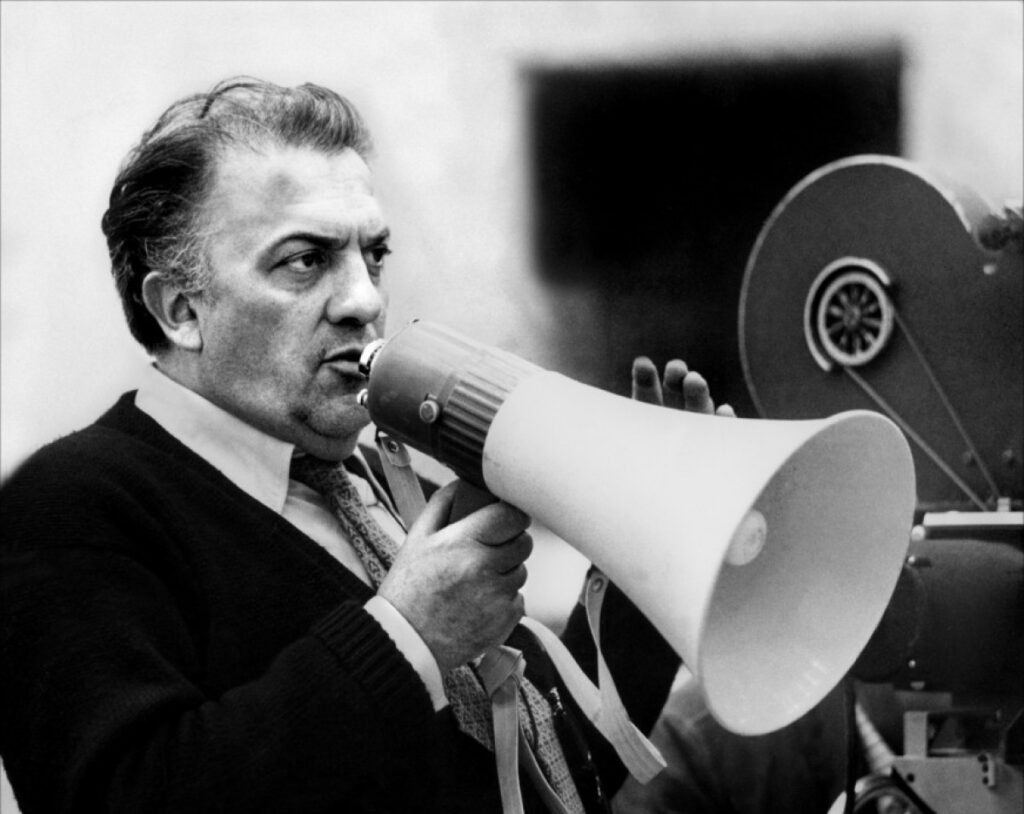

Fellini’s casting process was legendary, involving extensive “cattle calls” where he would interview and photograph hundreds of potential performers, looking not for conventional acting ability but for faces and bodies that expressed something essential about the characters as he imagined them. This approach resulted in the distinctive human landscape of his films—a gallery of memorable visages that collectively created what film scholar Peter Bondanella has called “a Fellinian universe.”

Musical Collaboration with Nino Rota

If Mastroianni and Masina gave human form to Fellini’s vision, composer Nino Rota gave it musical expression. Their collaboration, which began with The White Sheik and continued until Rota’s death in 1979, produced some of cinema’s most memorable scores. Rota’s music, which combined circus melodies, waltzes, and more traditional orchestral elements, complemented Fellini’s images with a similar blend of the melancholic and the whimsical.

The most famous product of their collaboration is undoubtedly the theme from La Dolce Vita, which captures both the film’s surface glamour and its underlying sadness. Similarly, the haunting melody associated with Gelsomina in La Strada becomes a motif that unites the film’s episodic structure while expressing the character’s innocent spirit.

After Rota’s death, Fellini collaborated with composer Luis Bacalov on City of Women and with Gianfranco Plenizio on his final films, but these later scores, while accomplished, lacked the perfect synchronicity that characterized his work with Rota.

The Role of Improvisation and the Script

Contrary to the common perception that his films were largely improvised, Fellini was a meticulous planner who developed detailed scripts and storyboards. However, he approached these materials as starting points rather than rigid blueprints, remaining open to the creative possibilities that emerged during production.

Fellini’s scripts, often developed in collaboration with writers like Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano, and Bernardino Zapponi, typically went through multiple revisions. Even after shooting began, Fellini continued to refine dialogue and action based on his interactions with actors and his evolving vision for the film.

This balance of preparation and spontaneity extended to his work with actors. While Fellini provided clear direction, he also created an atmosphere that allowed for genuine moments of discovery. Often, he would play music on set to establish a mood and help actors access emotional states beyond intellectual understanding. Additionally, rather than having actors memorize dialogue, he sometimes had them count numbers that would later be dubbed with the actual lines, a technique that produced a slightly artificial but emotionally authentic quality in performances.

Studio Work at Cinecittà and the Creation of Alternative Realities

Despite his early association with neorealism’s emphasis on location shooting, Fellini conducted most of his mature work within the controlled environment of Cinecittà studios in Rome. This shift reflected his growing interest in creating fully realized alternative realities rather than documenting existing ones.

Working with production designers like Dante Ferretti and Danilo Donati, Fellini transformed Cinecittà into landscapes of memory and imagination: the ancient Rome of Fellini Satyricon, complete with its grotesque banquet scenes and labyrinthine architecture; the oceanliner of And the Ship Sails On (E la nave va, 1983), constructed entirely on soundstages with a mechanical sea; the circus ring of The Clowns; and the provincial town square of Amarcord, where fascist rallies and peacock snowfalls coexist in the realm of heightened memory.

This preference for studio work allowed Fellini unprecedented control over every visual element, from lighting to costume to the physical characteristics of extras. It also freed him from the constraints of realism, enabling the creation of spaces that existed simultaneously as physical locations and states of mind—a fusion perfectly suited to his exploration of the porous boundaries between reality and imagination.

Later Career and Final Works

Artistic Freedom and Commercial Challenges

Following the worldwide success of La Dolce Vita and 8½, Fellini enjoyed a level of artistic freedom rarely granted to filmmakers. Producers were willing to finance his increasingly ambitious and personal projects despite their commercial uncertainty, a situation that allowed him to develop his distinctive style without compromise throughout the 1960s and early 1970s.

This period saw the creation of some of his most visually extravagant works: Juliet of the Spirits, his first color film, which used saturated hues and fantastic imagery to explore a housewife’s psychological liberation; Fellini Satyricon, a fragmented adaptation of Petronius that reimagined ancient Rome as an alien civilization; and Roma, a kaleidoscopic portrait of the Eternal City that combined personal memory with historical pageantry.

However, by the mid-1970s, changes in the film industry began to affect Fellini’s position. The global success of new Hollywood cinema, with its emphasis on youth-oriented genre films, made Fellini’s artistically ambitious, adult-oriented works seem increasingly unfashionable to international distributors. Additionally, the rise of television in Italy eroded cinema attendance, particularly for the kind of challenging art films Fellini produced.

These commercial pressures coincided with critical reassessment. While Amarcord (1973) won Fellini his fourth Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, subsequent works like Casanova (1976) and Orchestra Rehearsal (Prova d’orchestra, 1978) received more mixed responses, with some critics suggesting that Fellini was becoming self-parodic, recycling themes and images without the emotional depth of his earlier masterpieces.

Television Work and Commercials

In response to these challenges, Fellini, like many European art film directors of his generation, turned occasionally to television. His made-for-TV production Orchestra Rehearsal—an allegorical satire about a musical ensemble that descends into chaos when it rejects its conductor—reflected his concerns about the political and cultural upheavals of 1970s Italy while adapting to the smaller canvas of the television medium.

More surprisingly, Fellini also directed a series of television commercials in the 1980s, most notably for Campari and for the Bank of Rome. Far from regarding these as mere commercial assignments, Fellini approached these advertisements as miniature Fellini films, incorporating his characteristic visual style and thematic concerns into their brief running times. The Campari commercials, in particular, with their dreamlike imagery and celebration of pleasure, distilled the Felliniesque aesthetic into its purest form.

Final Films and Unfinished Projects

Fellini’s later theatrical features, while less commercially successful than his earlier masterpieces, contain moments of extraordinary beauty and represent significant artistic statements. And the Ship Sails On used the microcosm of a luxury liner carrying an opera company to explore themes of art, politics, and mortality. Ginger and Fred (1986) reunited Fellini with Masina and Mastroianni in a melancholy meditation on aging and the corrosive effects of television culture. Intervista (1987) found Fellini reflecting on his own career through a pseudo-documentary about a Japanese film crew visiting Cinecittà.

His final completed film, The Voice of the Moon (La voce della luna, 1990), starring Roberto Benigni as a poetic madman who believes he can hear the moon speaking to him, received a lukewarm critical response upon its release but has subsequently been reevaluated as a fitting conclusion to Fellini’s career—a gentle plea for listening to the poetic voices that modern society increasingly drowns out.

At the time of his death on October 31, 1993, Fellini was developing several projects that remained unrealized, including an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s Amerika and a film about the afterlife to be titled The Last Journey of Fellini. While these projects exist only in pre-production materials, they suggest that even in his seventies, Fellini continued to explore new creative territories.

Influence and Legacy

Impact on World Cinema

Federico Fellini’s influence extends across national boundaries and cinematic movements, making him one of the most referenced and emulated directors in film history. In his native Italy, filmmakers like Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso), Paolo Sorrentino (The Great Beauty), and Matteo Garrone (Reality) have acknowledged their debt to Fellini’s blend of memory, fantasy, and social observation, with Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty serving as a particularly conscious homage to La Dolce Vita.

In America, directors as diverse as Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, David Lynch, and Tim Burton have drawn inspiration from different aspects of Fellini’s work. Scorsese’s use of Catholic imagery and exploration of male anxiety echo Fellini’s similar concerns, while Lynch’s dreamlike narratives and surreal imagery in films like Mulholland Drive develop the syntax of the unconscious that Fellini pioneered in 8½. Allen explicitly referenced Fellini in Stardust Memories, a film that reworks the basic premise of 8½ within an American context.

Beyond individual filmmakers, entire movements have been shaped by Fellini’s example. The French New Wave directors admired his ability to create personal cinema within industrial constraints. The New German Cinema, especially Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s later works, drew on Fellini’s baroque visual style. And the magical realist tendency in Latin American cinema, exemplified by directors like Alejandro Jodorowsky and Emir Kusturica, owes much to Fellini’s fusion of the fantastical and the everyday.

Cultural Impact Beyond Cinema

Fellini’s influence extends beyond cinema into other art forms and popular culture. In literature, authors like Salman Rushdie and Gabriel García Márquez have acknowledged the impact of Fellini’s magical realism on their writing. In music, artists from Talking Heads (who named an album “Stop Making Sense” after a line from 8½) to Smashing Pumpkins (whose “1979” video references Amarcord) have drawn inspiration from Fellini’s imagery and themes.

The term “Felliniesque” has entered the international lexicon as a descriptor for anything characterized by fantastic imagery, carnival atmosphere, or surreal juxtapositions. Similarly, “paparazzi,” derived from the character Paparazzo in La Dolce Vita, has become the universal term for intrusive celebrity photographers, a linguistic testament to the film’s prescient criticism of media culture.

Fashion designers, including Dolce & Gabbana and Jean Paul Gaultier, have cited Fellini’s visual extravagance as an influence on their aesthetic. The black-and-white elegance of La Dolce Vita, in particular, continues to inform notions of Italian style and sophistication in global fashion.

Critical Reception and Academic Study

Fellini’s critical reputation has undergone several reassessments since his emergence in the 1950s. Initially celebrated for his contributions to neorealism, he was subsequently embraced by auteurist critics who valued his increasingly personal vision. During the height of semiotic and psychoanalytic film theory in the 1970s, Fellini’s work provided rich material for analyses focused on dreams, symbols, and the unconscious.

More recently, feminist and postmodern approaches have offered new perspectives on Fellini’s work, with scholars like Marguerite Waller reevaluating his representation of women and others exploring the ways in which his films deconstruct notions of authenticity and reality. The establishment of the Fondazione Federico Fellini in Rimini and the regular organization of academic conferences dedicated to his work ensure that scholarly engagement with his films continues to evolve.

In popular criticism, polls of critics and directors regularly place 8½ among the greatest films ever made, with La Dolce Vita, La Strada, and Amarcord also frequently appearing in such lists. Beyond these individual masterpieces, Fellini is consistently ranked among the most influential directors in cinema history, a testament to the enduring power of his artistic vision.

Preservation and Restoration Efforts

Ensuring the physical preservation of Fellini’s films has been a priority for film archives worldwide. The Cineteca di Bologna, in collaboration with Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, has undertaken the restoration of several Fellini masterpieces, including La Dolce Vita and 8½, using the latest digital technologies to return these works to their original visual splendor.

These restoration efforts are complemented by the preservation of Fellini’s drawings, scripts, and production materials in archives like the Fellini Collection at the University of Indiana’s Lilly Library and the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome. These materials provide invaluable resources for scholars studying Fellini’s creative process and the evolution of his visual imagination.

Additionally, numerous books, documentaries, and exhibitions have helped to contextualize Fellini’s achievement for new generations of viewers. Exhibitions of his drawings and set designs have toured major museums worldwide, while documentaries like Damian Pettigrew’s Fellini: I’m a Born Liar (2002) offer intimate perspectives on his working methods and philosophical outlook.

Philosophy and Worldview

Dreams, Jung, and the Unconscious

Central to understanding Fellini’s artistic vision is his profound interest in dreams and the unconscious mind. Influenced by his encounter with Jungian psychology in the 1960s, Fellini came to see dreams not as mere nocturnal diversions but as communications from the deeper self that could inform his creative work and personal development.

Beginning in 1960, during the filming of La Dolce Vita, Fellini began keeping detailed records of his dreams in journals that combined verbal descriptions with colorful illustrations. This practice, which he maintained for decades, became integral to his creative process and directly informed films like 8½, Juliet of the Spirits, and City of Women, all of which incorporate dream sequences that blur the boundary between objective reality and subjective experience.

Fellini’s fascination with Jungian concepts—particularly the collective unconscious and archetypal figures—provided him with a framework for understanding the universal resonance of certain images and characters. The recurring figure of the clown in his work, for instance, embodied what Jung might have called the “trickster” archetype, while the imposing female figures who populate 8½ and City of Women represent various aspects of the anima, or feminine principle in the male psyche.

Beyond Jung, Fellini was influenced by other explorations of the unconscious, including the surrealist movement in art and the work of filmmakers like Luis Buñuel who prioritized dream logic over narrative coherence. However, what distinguished Fellini’s approach to the unconscious was his integration of dreamlike elements within films that maintained emotional coherence, creating works that engaged viewers on multiple levels simultaneously.

Views on Cinema and Art

Throughout his career, Fellini articulated a distinctive philosophy of cinema that emphasized its capacity for personal expression over social criticism or entertainment. “I make films the way I paint,” he once remarked, “and I paint them the way I live—I make them to discover myself and my relation to things.”

This conception of film as self-discovery led Fellini to reject both the strict social realism of his neorealist beginnings and the political cinema that dominated European art film in the 1960s and 1970s. While contemporaries like Jean-Luc Godard and Pier Paolo Pasolini created explicitly political works, Fellini maintained that the artist’s primary responsibility was to personal truth rather than ideological commitment.

This position sometimes led to criticism from leftist intellectuals who viewed Fellini’s increasingly personal and fantastical films as decadent or escapist. He defended his approach by arguing that authentic art was inherently political precisely because it challenged conventional thinking and expanded human consciousness. “The artist’s task,” he said, “is to reveal and expand the universal human.”

Despite his emphasis on personal expression, Fellini remained deeply connected to popular traditions of storytelling and spectacle. His films drew on circus performance, vaudeville, comic strips, and other forms of “low” culture that he elevated through his artistic vision. This democratic approach to cultural influences reflected his belief that cinema was uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between elite and popular art forms.

Political and Social Attitudes

While Fellini avoided explicit political statements in his films, his work nevertheless embodied certain consistent social and political attitudes. Chief among these was a skepticism toward all forms of authoritarianism and dogma, whether fascist, communist, or religious.

This skepticism was rooted in his experiences growing up under Mussolini’s regime, which taught him to distrust grand ideological narratives and mass movements. In films like Amarcord, he satirized fascism not through direct critique but by exposing its absurdity and theatricality, showing how it appealed to adolescent fantasies of power and belonging.

Similarly, Fellini maintained a critical distance from the Catholic Church despite his lifelong fascination with its rituals and imagery. Films like Roma, with its surreal ecclesiastical fashion show, and La Dolce Vita, with its false miracle and decadent religious tourism, suggest an institution that has exchanged spiritual substance for empty spectacle.

More broadly, Fellini’s films express concern about the dehumanizing aspects of modernity: consumerism, mass media, and technological progress divorced from human values. This critique is particularly evident in later works like Ginger and Fred, which laments television’s degradation of authentic performance into commodified entertainment.

However, counterbalancing this cultural pessimism is Fellini’s celebration of individual freedom and creativity as responses to social alienation. His films suggest that while collective ideologies may fail, personal imagination and human connection offer paths to meaning and fulfillment even in disenchanted times.

Personal Life and Character

Marriage to Giulietta Masina

No account of Fellini’s life and art would be complete without acknowledging the profound importance of his relationship with Giulietta Masina, whom he married in 1943 and remained with until his death fifty years later. Their partnership was both personal and creative, with Masina starring in some of Fellini’s most beloved films and serving as a stabilizing influence in his often chaotic life.

Masina and Fellini met in 1942 when he was working as a scriptwriter for a radio program in which she performed. Their courtship was brief—they married the following year during the tumultuous period of Nazi occupation—but their relationship would prove remarkably enduring despite significant challenges, including Fellini’s well-documented infidelities and the tragic death of their son Pierfederico just two weeks after his birth in 1945.

What sustained their marriage was a deep mutual respect and complementary temperaments. While Fellini was expansive, gregarious, and given to flights of fantasy, Masina was practical, disciplined, and grounded. She managed their household and often their finances, creating the stable foundation that allowed Fellini’s imagination to flourish. “She is the person who has understood me the most,” Fellini once remarked. “She has inspired me the most, protected me, helped me, put up with me.”

The characters Masina portrayed in Fellini’s films—particularly Gelsomina in La Strada and Cabiria in Nights of Cabiria—reflected aspects of her own personality while also serving as counterpoints to the more cynical male characters who often represented elements of Fellini himself. Through these roles, she embodied a kind of spiritual resilience that balanced the director’s darker explorations of disillusionment and despair.

The depth of their connection was poignantly illustrated by Masina’s death on March 23, 1994, just months after Fellini’s own passing. Many who knew them felt that she had simply lost the will to live without her husband, bringing a fitting conclusion to one of cinema’s great love stories.

Relationships with Collaborators and Friends

Beyond his marriage, Fellini maintained a complex network of professional and personal relationships that nourished his creativity. He was known for inspiring intense loyalty among his regular collaborators, from actors like Marcello Mastroianni and Sandra Milo to behind-the-scenes artists like cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno and composer Nino Rota.

These collaborations were characterized by Fellini’s ability to communicate his vision clearly while remaining open to the contributions of others. Mastroianni, in particular, enjoyed a relationship with Fellini that went beyond director and actor to become a genuine friendship based on mutual admiration. “Working with Federico,” Mastroianni once said, “is like going to a party. He creates an atmosphere of such joy on the set that it’s impossible not to give your best.”

Fellini also maintained friendships with fellow directors like Michelangelo Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, and Roberto Rossellini, though these relationships were sometimes complicated by professional rivalry and differing artistic visions. His connection with Rossellini, who had given him his start in cinema, evolved from apprenticeship to collegial respect as Fellini developed his own distinctive style.

In his later years, Fellini became something of a guru figure for younger filmmakers who sought his advice and blessing. Directors like Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, and David Lynch made pilgrimages to Rome to meet him, testament to his status as cinema’s elder statesman and visionary.

Daily Habits and Creative Process

Fellini maintained remarkably consistent work habits throughout his career. He typically rose early, around 5:00 AM, and began his day by sketching dreams and ideas in notebooks that served as visual diaries. These drawings—sometimes whimsical, sometimes grotesque—were not merely preliminary work for his films but an independent creative outlet that helped him process his unconscious material.

After this solitary morning ritual, Fellini would often meet with writers or production designers to develop projects. He preferred to work at the Bar Canova in Piazza del Popolo or at his favorite table at Cinecittà’s commissary rather than in a formal office, finding the ambient noise and casual atmosphere more conducive to creativity than silence and isolation.

During production, Fellini was completely immersed in his films, working long hours on set while maintaining an atmosphere that was simultaneously disciplined and playful. He insisted on absolute control over every aspect of production while also creating space for spontaneity and discovery. This paradoxical approach—rigorous planning combined with openness to the moment—characterized his entire creative process.

Though known for his exuberant public persona, those close to Fellini described a more complex individual who alternated between periods of intense sociability and introspective withdrawal. He suffered from occasional bouts of depression and insomnia, which he processed through his art rather than therapy. “All my films turn upon this struggle,” he once admitted, “between my need to establish a secure shelter for myself and my deep-seated desire to go out into life, to participate.”

Conclusion: The Enduring Magic of Fellini’s Vision

Federico Fellini’s evolution from neorealist screenwriter to visionary auteur represents one of the most remarkable artistic journeys in cinema history. Through works of increasing complexity and personal expression, he expanded the language of film, demonstrating its capacity to capture not just external reality but the interior landscapes of memory, dream, and desire.

What distinguishes Fellini’s achievement is not just his technical innovation or visual splendor but the profound humanism that animates even his most fantastical creations. Behind the baroque surfaces and carnivalesque spectacles of his films lies a deep engagement with fundamental human questions: How do we find meaning in a world of constant change? How do we reconcile our spiritual longings with our earthly desires? How do we maintain authenticity in societies that encourage performance and disguise?

Fellini’s answers to these questions were never dogmatic or reductive. Instead, his films offer something more valuable: a vision of life that embraces contradiction, celebrates diversity, and finds beauty in the full spectrum of human experience, from the sublime to the ridiculous. In doing so, they fulfill what Fellini himself described as the ultimate purpose of his art: “to make people aware of something they should already know: that there is someone beside you who is suffering… to discover we’re all the same and that our destiny is the destiny of everyone.”

In an age increasingly dominated by formula and spectacle, Fellini’s deeply personal cinema offers a reminder of film’s capacity to transform subjective experience into universal art. His greatest works are not mere entertainments or statements but invitations to see the world through different eyes—to recognize, as he put it, that “there is no end. There is no beginning. There is only the infinite passion of life.”

This passion—for beauty, for human variety, for the mysterious interplay of reality and imagination—remains Fellini’s greatest legacy. It ensures that, decades after his death, his films continue to enchant, provoke, and inspire viewers worldwide, affirming cinema’s status as the art form perhaps best suited to capturing the dreams that make us human.