In the pantheon of world cinema, few filmmakers have captured the essence of human experience with such sublime simplicity and profound depth as Satyajit Ray. Born on May 2, 1921, in Calcutta (now Kolkata), Ray emerged as India’s most celebrated filmmaker, whose work transcended national boundaries to achieve universal acclaim. His masterful direction, particularly evident in his magnum opus, The Apu Trilogy, established him as one of the most influential directors of the 20th century.

Early Life and Influences

Ray was born into a prominent Bengali family with deep literary roots. His grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, was a renowned writer, painter, and printing technologist, while his father, Sukumar Ray, gained fame as a pioneering humorist and illustrator. Despite losing his father at the tender age of two, Ray inherited this creative legacy.

After graduating from Presidency College, Ray attended Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, founded by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. Here, under the tutelage of celebrated artists like Nandalal Bose, Ray developed a keen aesthetic sensibility and appreciation for both Western and Eastern artistic traditions.

Ray’s cinematic awakening came in 1947 when he met French filmmaker Jean Renoir, who was in Calcutta to scout locations for “The River.” Their conversations ignited Ray’s passion for cinema. Later, while working as a graphic designer at an advertising agency, Ray saw Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece “Bicycle Thieves” during a trip to London. The film’s honest portrayal of ordinary life convinced Ray that he could make films about Indian reality with minimal resources.

The Apu Trilogy: A Landmark in World Cinema

Ray’s debut film, “Pather Panchali” (Song of the Little Road, 1955), marked the beginning of what would become the celebrated Apu Trilogy. Shot over three years with an inexperienced crew and a shoestring budget, the film chronicles the childhood of Apu, a young boy growing up in rural Bengal in the early 20th century.

“Pather Panchali” stunned the world with its poetic imagery, naturalistic performances, and emotional resonance. When screened at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, it won the “Best Human Document” award, introducing Ray to international audiences and establishing his reputation as a major filmmaker.

The trilogy continued with “Aparajito” (The Unvanquished, 1956), which follows adolescent Apu as he moves to Benares with his mother after his father’s death. The film explores Apu’s educational journey and the growing distance from his rural roots, culminating in his mother’s death and his realization of profound solitude.

“Apur Sansar” (The World of Apu, 1959) completes this cinematic bildungsroman, portraying Apu as a young man who dreams of becoming a writer. After an unexpected marriage to Aparna (portrayed by the luminous Sharmila Tagore in her debut), Apu experiences brief happiness before tragedy strikes again. The film concludes with Apu’s reunification with his son and their journey toward a new beginning.

The Trilogy’s Artistic Achievement

What distinguishes The Apu Trilogy is Ray’s unique blend of neorealism with a distinctly Bengali sensibility. His camera captures the everyday with reverence—whether it’s children running through fields to catch a glimpse of a train, raindrops falling on a pond, or the quiet intimacy between mother and son.

Ray eschewed melodrama, instead finding poetry in stillness and truth in observation. Working with cinematographer Subrata Mitra and art director Bansi Chandragupta, he created visual compositions of stunning beauty despite technical limitations. Ravi Shankar’s evocative soundtrack, with its sitar-driven themes, perfectly complemented the visuals, becoming an integral part of the narrative tapestry.

The trilogy’s greatest achievement lies in its deeply humane portrayal of character. Apu’s journey from wide-eyed child to grief-stricken adult unfolds with remarkable psychological authenticity. Ray depicted the harsh realities of poverty and loss without sentimentality, yet infused his narrative with moments of transcendent joy and beauty.

Beyond The Apu Trilogy

While The Apu Trilogy remains Ray’s most celebrated work, his filmography encompasses remarkable diversity. “The Music Room” (1958) examines a decaying aristocrat’s obsession with music. “Charulata” (1964), often considered his most perfect film, delves into the emotional awakening of a neglected wife in Victorian-era Bengal. “Days and Nights in the Forest” (1970) studies urban characters against a rural backdrop, while “Distant Thunder” (1973) addresses the devastating Bengal famine of 1943.

Ray also made films for children, detective stories based on his own Feluda character, and documentaries, including one on Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. His later works like “The Home and the World” (1984) and “The Stranger” (1991) are more overtly political, engaging with issues of nationalism, religious fundamentalism, and scientific rationality.

Ray’s Cinematic Language

Ray developed a distinctive cinematic language characterized by long takes, deep focus, and minimal camera movement. His editing was unobtrusive, prioritizing rhythm and emotional continuity over flashy transitions. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Ray avoided obvious symbolism, preferring to let meaning emerge organically from character and situation.

His approach to actors was equally remarkable. Working with a mix of professionals and non-professionals, Ray elicited performances of extraordinary naturalism. He often cast against type and was particularly skilled at directing children, capturing authentic childlike behavior rarely seen in cinema before.

Global Recognition and Legacy

The international film community recognized Ray’s genius early. Besides his debut triumph at Cannes, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, including the Golden Lion at Venice for “Aparajito” and multiple Silver Bears at Berlin. In 1992, while on his deathbed, Ray received an Honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement—the first Indian to receive this honor.

Ray’s influence extends far beyond India. Filmmakers as diverse as Martin Scorsese, Akira Kurosawa, Abbas Kiarostami, and Wes Anderson have acknowledged their debt to him. His work helped establish the artistic legitimacy of Asian cinema on the world stage and demonstrated that authentically local stories could achieve universal resonance.

In India, Ray challenged the dominant commercial cinema with his artistic integrity and commitment to realism. The “parallel cinema” movement that emerged in the 1970s and ’80s would have been unthinkable without his pioneering example.

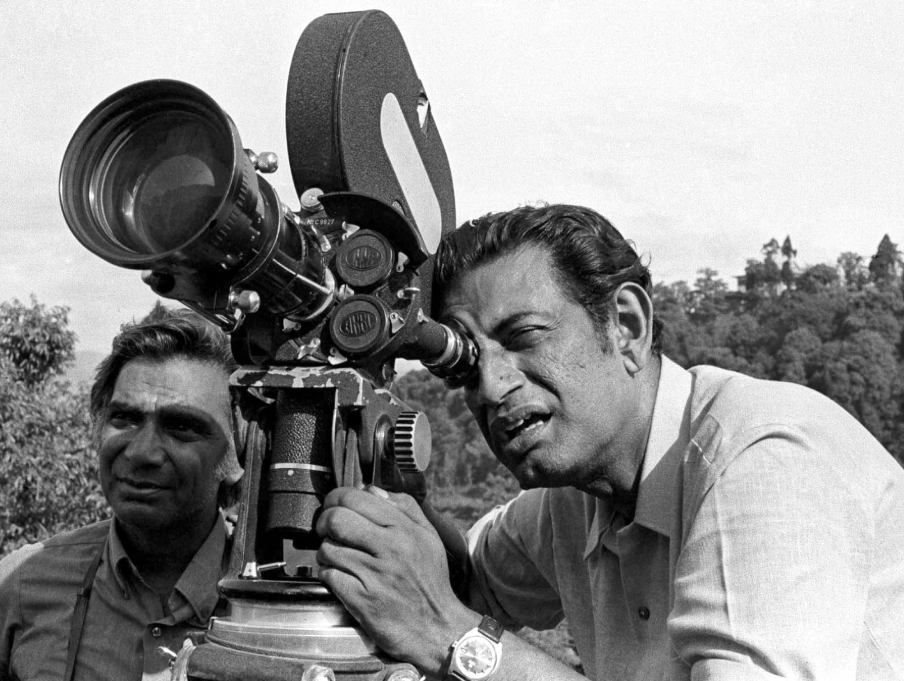

The Man Behind the Camera

Beyond filmmaking, Ray was a renaissance man whose talents spanned multiple disciplines. He was an accomplished musician who composed the scores for his later films. As a graphic designer, he revolutionized Bangla typography and book design. He was also a prolific writer of short stories, novels, and essays on cinema.

Those who worked with Ray described him as a gentle but authoritative presence on set. Standing at six-foot-four, he had a commanding physical presence but was known for his soft-spoken manner and meticulous preparation. Ray storyboarded his films in detail, creating visual scripts with drawings that anticipated every shot.

Conclusion

Satyajit Ray’s cinema represents a perfect synthesis of Eastern and Western artistic traditions, combining the humanistic concerns of European neorealism with the contemplative sensibility of Bengali culture. Through The Apu Trilogy and his subsequent works, Ray created a body of work that speaks to the universal human condition while remaining deeply rooted in the specifics of Bengali life.

Ray once wrote: “The only solutions I know to the problems of filmmaking are relentlessly indigenous ones.” This commitment to cultural authenticity, combined with his profound humanism, enabled him to create films that continue to move audiences across cultural and temporal boundaries. In an era of increasing globalization, Ray’s cinema reminds us that true universality emerges not from homogenization but from the honest and compassionate exploration of particular human experiences.

As we continue to revisit Ray’s oeuvre, especially The Apu Trilogy, we reconnect with a vision of cinema as not merely entertainment or even art, but as a form of seeing that enlarges our capacity for empathy and deepens our understanding of what it means to be human. This, perhaps, is Satyajit Ray’s greatest legacy.