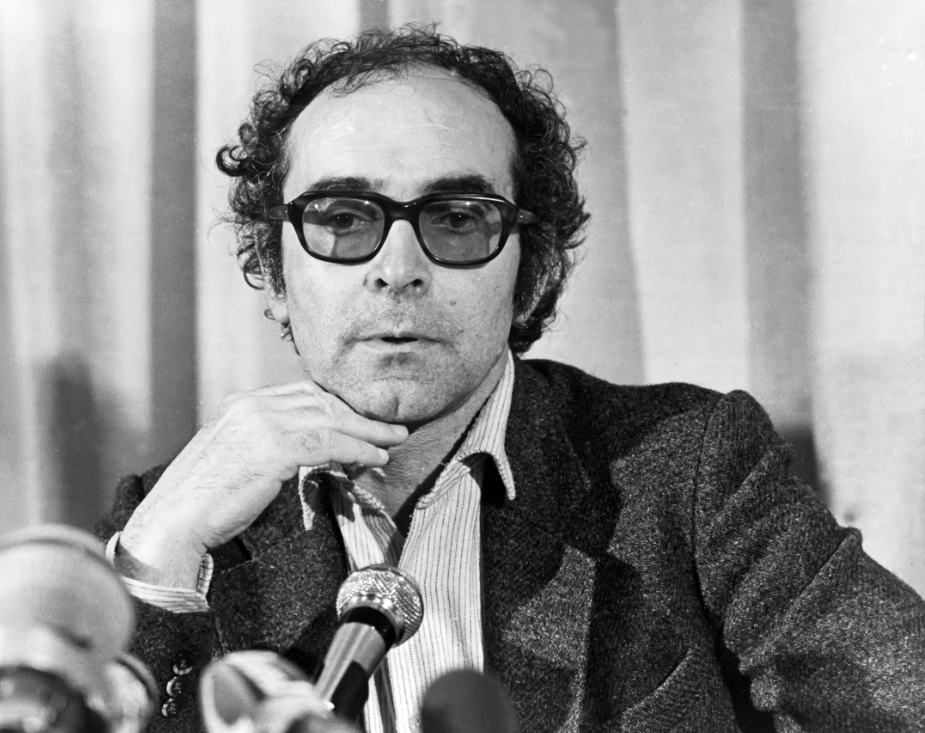

Jean-Luc Godard is one of cinema’s most revolutionary figures, a filmmaker whose radical approach to storytelling, visual language, and political engagement fundamentally transformed how movies could be made and understood. From his emergence as a leading voice of the French New Wave in the late 1950s to his continued experimentation until his death in 2022, Godard consistently challenged conventional filmmaking practices, creating a body of work that remains as provocative and influential today as it was groundbreaking decades ago.

The Making of a Revolutionary

Born in Paris in 1930 to a Franco-Swiss family, Godard’s path to cinema began not behind a camera but in the pages of Cahiers du Cinéma, the influential film magazine that would become the intellectual breeding ground for the French New Wave. Alongside future directors François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, and Claude Chabrol, Godard wrote passionate film criticism that championed the works of American directors like Howard Hawks, John Ford, and Nicholas Ray, while simultaneously developing a theoretical framework that would later inform his own filmmaking.

The young critics at Cahiers du Cinéma developed what became known as the auteur theory, arguing that the director was the primary creative force behind a film, comparable to an author of literature. This perspective would prove foundational to Godard’s approach as a filmmaker, where personal expression and artistic vision took precedence over commercial considerations or traditional narrative structures.

Breathless: The Birth of a New Cinema

Godard’s transition from critic to filmmaker culminated in 1960 with Breathless (À bout de souffle), a film that would become both his calling card and a manifesto for the New Wave movement. Made on a shoestring budget with handheld cameras, natural lighting, and improvised dialogue, Breathless told the story of a small-time criminal (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and his American girlfriend (Jean Seberg) with a spontaneity and energy that felt completely fresh.

The film’s technical innovations were as important as its narrative content. Godard employed jump cuts that violated classical editing principles, breaking the illusion of seamless continuity that had dominated cinema since its inception. Characters spoke directly to the camera, acknowledging the audience’s presence and demolishing the fourth wall. The cinematography, handled by Raoul Coutard, captured the vitality of Paris streets with a documentary-like immediacy that made the city itself a character in the story.

Breathless was more than just a stylistic exercise; it represented a democratization of filmmaking. By proving that compelling cinema could be made quickly and cheaply without studio resources, Godard opened doors for countless independent filmmakers who would follow. The film’s success also established many of the aesthetic and philosophical principles that would define not just Godard’s career, but the entire New Wave movement.

The New Wave Revolutionary

As a central figure in the French New Wave, Godard embodied the movement’s rejection of the “cinema de papa” – the polished, literary adaptations and studio productions that had dominated French filmmaking in the 1950s. The New Wave filmmakers sought to create a more personal, immediate cinema that reflected contemporary life and embraced the medium’s unique properties rather than borrowing prestige from theater or literature.

Godard’s contributions to this movement extended beyond his individual films to his role as a theorist and provocateur. His writings and interviews articulated a vision of cinema as an art form capable of intellectual and emotional complexity, while his films demonstrated these principles in practice. Unlike some of his New Wave contemporaries who eventually moved toward more conventional storytelling, Godard remained consistently experimental, using each new project to push further into uncharted territory.

The New Wave’s influence on international cinema was profound, inspiring similar movements around the world. From the American New Hollywood directors of the 1970s to contemporary independent filmmakers, Godard’s innovations in narrative structure, visual style, and production methods continue to resonate. His demonstration that films could be made outside traditional studio systems while maintaining artistic integrity provided a template that remains relevant in today’s digital filmmaking landscape.

Evolution of Style and Vision

Throughout the 1960s, Godard’s films became increasingly experimental and politically engaged. Works like Vivre sa Vie (1962), Contempt (1963), and Pierrot le Fou (1965) combined his ongoing formal innovations with deeper explorations of contemporary social and philosophical issues. Vivre sa Vie, structured as twelve episodes in the life of a prostitute, examined questions of freedom and authenticity with a documentary-like objectivity that influenced countless subsequent filmmakers.

Contempt, starring Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli, offered Godard’s meditation on the film industry itself, while also serving as an homage to classical Hollywood cinema and its directors. The film’s famous opening sequence, featuring Bardot and Piccoli in bed discussing their relationship in real-time, exemplified Godard’s ability to transform mundane moments into cinematic poetry through his unique approach to time, space, and dialogue.

By the late 1960s, Godard’s work became more overtly political, culminating in films like Weekend (1967) and La Chinoise (1967). These works abandoned conventional narrative almost entirely in favor of political essay-films that combined fictional elements with documentary techniques, theoretical discussions, and direct political commentary. Weekend, with its famous traffic jam sequence and apocalyptic vision of bourgeois society, represented both the culmination of Godard’s 1960s period and a bridge to his more radical subsequent work.

The Revolutionary Period and Beyond

The events of May 1968 in Paris profoundly impacted Godard’s artistic trajectory. He became increasingly involved with leftist political movements and began creating films that prioritized political message over entertainment value. Working with the Dziga Vertov Group, named after the Soviet montage filmmaker, Godard produced a series of revolutionary films that challenged not just cinematic conventions but the entire capitalist system that supported commercial filmmaking.

Films from this period, such as Wind from the East (1970) and Pravda (1969), were deliberately difficult and confrontational, designed to provoke political consciousness rather than provide entertainment. While these works limited Godard’s commercial appeal, they demonstrated his commitment to using cinema as a tool for social and political change, establishing him as one of the few major filmmakers willing to completely abandon commercial considerations in pursuit of artistic and political principles.

The 1980s saw Godard’s return to more accessible filmmaking with works like Every Man for Himself (1980) and First Name: Carmen (1983), though he never abandoned his experimental approach. His later period was marked by an increasingly philosophical and reflective tone, culminating in his massive eight-part video essay Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1988-1998), a meditation on cinema’s relationship to 20th-century history that many consider his masterpiece.

Visual Language and Innovation

Godard’s revolutionary approach to cinema extended far beyond narrative structure to encompass every aspect of visual and auditory expression. His use of color was particularly distinctive, often employing bold, primary colors in ways that called attention to cinema’s artificial nature rather than creating realistic environments. The famous red, white, and blue color scheme in Pierrot le Fou, for instance, served both aesthetic and symbolic functions, connecting the film’s visual design to broader themes about French identity and cultural politics.

His approach to sound was equally innovative. Godard frequently separated sound from image, using voice-over narration that contradicted visual information or incorporating ambient sounds that created emotional or intellectual associations rather than realistic soundscapes. His films often featured direct address to the audience, whether through characters speaking to the camera or through intertitles that provided commentary on the action.

Typography and text played crucial roles in Godard’s visual language. His films frequently incorporated written words, whether through intertitles, signs within the frame, or text overlaid on images. This integration of literary and cinematic elements reflected his background as a critic and writer, while also acknowledging cinema’s relationship to other forms of communication and expression.

Influence on Contemporary Cinema

Godard’s influence on subsequent filmmakers cannot be overstated. Directors across multiple generations have drawn inspiration from his technical innovations, narrative approaches, and artistic philosophy. The American New Hollywood directors of the 1970s, including Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, and Terrence Malick, incorporated Godardian techniques into their own work, helping to bring European art cinema sensibilities to American filmmaking.

Contemporary directors continue to reference and build upon Godard’s innovations. Quentin Tarantino’s non-linear narratives and self-reflexive style show clear Godardian influences, while directors like Chantal Akerman, Abbas Kiarostami, and Jia Zhangke have developed their own approaches to art cinema that build upon foundations Godard established. Even mainstream filmmakers occasionally employ techniques pioneered by Godard, demonstrating the extent to which his innovations have become part of cinema’s common vocabulary.

Beyond specific technical influences, Godard’s broader approach to filmmaking as an intellectual and artistic practice has inspired countless filmmakers to view cinema as a medium capable of philosophical complexity and political engagement. His demonstration that films could be both entertaining and intellectually challenging, both personal and universal, established a template for art cinema that remains vital today.

Political Cinema and Social Commentary

Throughout his career, Godard maintained that cinema was inherently political, not just in its content but in its methods of production and distribution. His films consistently examined power structures, whether in personal relationships, economic systems, or cultural institutions. Even his seemingly apolitical early works contained subtle critiques of bourgeois values and conventional social arrangements.

Godard’s political cinema went beyond simple message-making to examine the ways in which images and narratives shape consciousness and social understanding. His films often revealed the constructed nature of cinematic reality, encouraging audiences to question not just the specific stories being told but the broader systems of representation that shape how we understand the world.

This political dimension of Godard’s work has proven especially influential in an era of media saturation and digital manipulation. His early insights into the power of images and the importance of understanding how visual media shapes perception seem remarkably prescient in today’s context of social media, fake news, and digital propaganda.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Jean-Luc Godard’s death in September 2022 marked the end of one of cinema’s most remarkable careers, but his influence continues to shape filmmaking around the world. His technical innovations have become standard tools in the filmmaker’s toolkit, while his philosophical approach to cinema as an art form continues to inspire directors who view their work as more than entertainment.

Perhaps most importantly, Godard demonstrated that cinema could maintain its popular appeal while engaging with serious intellectual and political questions. His best films combined entertainment value with genuine philosophical depth, proving that audiences were capable of engaging with complex, challenging material when it was presented with sufficient artistry and passion.

The digital revolution in filmmaking has made Godard’s low-budget, independent approach more relevant than ever. Contemporary filmmakers working with minimal resources can look to Godard’s example for inspiration on how to create meaningful cinema without studio backing or major financial investment. His emphasis on personal vision over commercial considerations remains a vital message for artists working in an increasingly commercialized media landscape.

Godard’s exploration of cinema’s relationship to other art forms – literature, painting, music – also seems particularly relevant in an era of multimedia and cross-platform storytelling. His recognition that cinema exists in dialogue with other forms of cultural expression anticipated many of the developments that define contemporary media culture.

Conclusion

Jean-Luc Godard’s career represents one of the most sustained and successful attempts to expand cinema’s artistic and intellectual possibilities. From Breathless to his final works, he consistently challenged both filmmakers and audiences to think more deeply about the medium’s potential for expression and communication. His technical innovations changed how films could be made, while his theoretical contributions changed how films could be understood.

More than six decades after Breathless first shocked audiences with its radical approach to storytelling and visual style, Godard’s influence remains as vital as ever. His films continue to inspire new generations of filmmakers, while his example as an artist committed to personal vision over commercial success provides a model for creative independence that transcends cinema to influence artists working in all media.

Godard proved that cinema could be simultaneously popular and intellectual, entertaining and challenging, personal and political. In doing so, he expanded the medium’s possibilities in ways that continue to resonate today, ensuring his place not just as a significant filmmaker but as one of the most important artists of the 20th century. His legacy reminds us that great art often emerges from the willingness to break rules, challenge conventions, and pursue personal vision with unwavering dedication – lessons that remain as relevant today as they were when a young critic first picked up a camera and decided to revolutionize cinema.