The sudden, inexplicable silence that followed the roar of the dragon in 1973 left an unprecedented void in the global cinematic landscape. Bruce Lee, a man who had transcended martial arts to become a global superstar, was gone. His death at the tragically young age of 32 sent shockwaves across the world, particularly in his native Hong Kong and the burgeoning international martial arts film market. Yet, even before the mourning period could truly begin, a curious and controversial cinematic phenomenon began to take root, blossoming rapidly in the shadow of his colossal legacy: “Bruceploitation.” This subgenre, born out of a potent mix of grief, opportunism, and insatiable demand, would flood screens with films starring myriad “Bruce Lee look-alikes,” attempting to fill the void with varying degrees of success, and forever cementing its place as a bizarre, often cynical, yet undeniably significant chapter in cinematic history.

The Genesis of a Phenomenon: Capitalizing on a Chasm

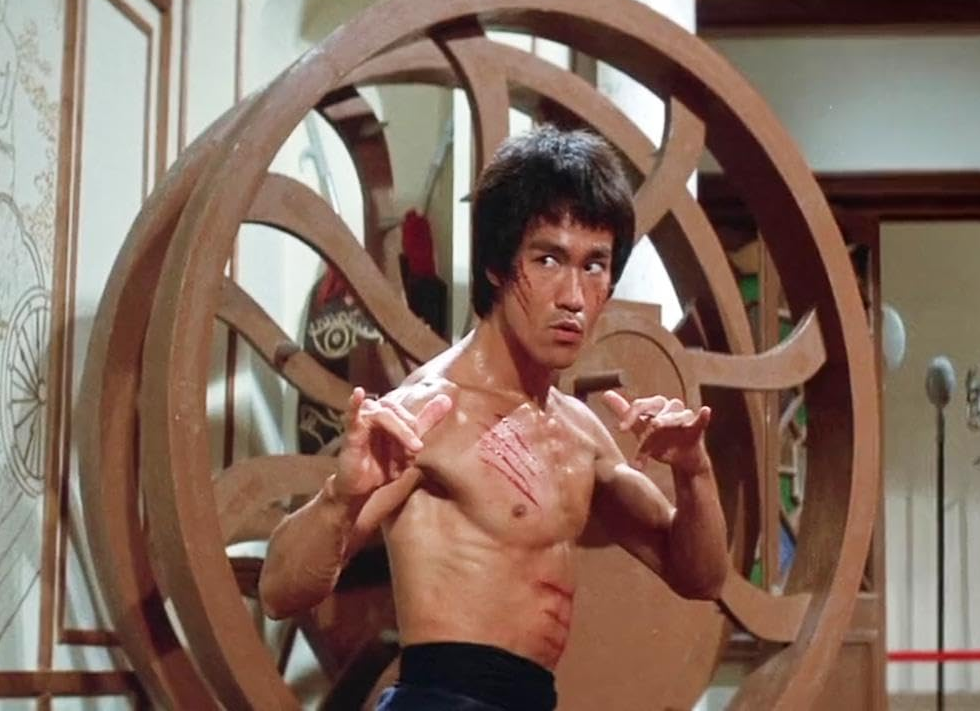

To understand Bruceploitation, one must first grasp the sheer magnitude of Bruce Lee’s impact. He wasn’t just a martial artist; he was a cultural icon who shattered stereotypes, redefined action cinema, and embodied an electrifying charisma previously unseen. His films – The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, The Way of the Dragon, and the posthumously released Enter the Dragon – had ignited a global kung fu craze. When he died, the demand for more Bruce Lee was insatiable, and the supply had ceased.

This unfillable void created a unique commercial imperative. Hong Kong film studios, inherently entrepreneurial and quick to adapt, recognized the vacuum. The thought process was brutally simple: if the original was gone, an imitation would have to suffice. Audiences, hungry for more of the lightning-fast kicks, the piercing glare, the nunchaku mastery, and the signature high-pitched kiai, were seen as ripe for exploitation. Within months of Lee’s passing, the first wave of Bruceploitation films began to emerge, often rushed into production with minimal budgets and even less creative oversight. The goal was not artistic merit but rapid turnover and maximum profit, leveraging the global fascination with the deceased star.

Characteristics of the Imitation Game: The Anatomy of Bruceploitation

The distinct hallmarks of Bruceploitation films quickly became apparent, forming a recognizable, if often repetitive, template.

The “Look-Alikes”: More Than Just a Face

Central to the Bruceploitation phenomenon were the myriad actors who stepped into the Dragon’s shadow. These individuals, often discovered for their physical resemblance to Lee or their martial arts prowess, were tasked with embodying an icon. Their performances ranged from uncanny mimicry to outright caricature.

- Bruce Li (Ho Chung-tao): Perhaps the most prolific and arguably the most successful of the imitators, Bruce Li wasn’t merely a look-alike; he was a competent martial artist with a genuine screen presence. His films, such as Exit the Dragon, Enter the Tiger (1976) and The Dragon Lives Again (1977), often positioned him as a more serious successor, attempting to replicate Lee’s intensity and dramatic flair. Li even tried to distance himself from the direct imitation later in his career, seeking to forge his own identity, though his fame remained inextricably linked to Lee.

- Dragon Lee (Moon Kyeong-min): A South Korean taekwondo practitioner, Dragon Lee was known for his incredible physique and powerful kicks. His films, including The Clones of Bruce Lee (1980) and Dragon Lee Fights Back (1979), often leaned into more overtly violent and less subtle action, showcasing his athleticism rather than Lee’s nuanced Wing Chun.

- Bruce Le (Huang Kin-lung): Strikingly similar in appearance to Lee, Bruce Le’s career was marked by some of the most bizarre and often self-referential Bruceploitation titles, such as Bruce and Shaolin Kung Fu (1977) and Return of Bruce (1977). He possessed a remarkable physical resemblance but often lacked the controlled intensity and precision of the original, leading to more exaggerated performances.

- Other Notable Imitators: The roster extended far beyond these three, encompassing a bewildering array of “Bruces”: Bruce Lai, Bruce Lo, Bruceshi, Myron Bruce Lee, and even female imitators like “Bruce Lee’s Sister.” Each attempted to capture some essence of the original, whether through signature gestures, vocalizations, or costume choices, often with comical or unsettling results. Their success in convincing audiences varied wildly, from Li’s earnest attempts to Le’s more cartoonish portrayals.

Recycled Tropes and Storylines: A Familiar Yet Distorted World

Narrative originality was rarely a priority in Bruceploitation. Instead, filmmakers liberally borrowed from Bruce Lee’s own filmography, twisting and combining elements to create new, often convoluted plots. Revenge narratives were paramount, mirroring Fist of Fury‘s central theme. Characters would seek retribution for the murder of a master, a family member, or a fellow student. Martial arts tournaments, akin to Enter the Dragon, provided convenient frameworks for showcasing various fighting styles. Confronting foreign oppressors, particularly Japanese villains (a common trope in Lee’s films), was also a recurring motif, tapping into nationalist sentiments.

The plots were frequently thin, serving primarily as vehicles for fight sequences. Character development was minimal, and logical coherence often took a backseat to the exigencies of low-budget production. Many films even featured a “Bruce Lee” character who wasn’t explicitly named Bruce Lee but was clearly meant to be him, often returning from the dead or being a long-lost brother or clone. This created a peculiar meta-narrative, where the films themselves acknowledged their imitative nature, albeit often unintentionally.

Fight Choreography – The Imitation Game:

Bruce Lee’s fighting style was revolutionary: swift, fluid, powerful, and intensely personal. Bruceploitation films, while attempting to emulate this, often fell short. The choreography tended to be less refined, relying more on quick cuts, exaggerated sound effects, and an overabundance of Lee’s signature mannerisms. High-pitched kiai, repetitive finger-pointing gestures, and the ubiquitous nunchaku became almost parodic in their frequent, often gratuitous, use. While some imitators, like Bruce Li, were genuinely skilled martial artists, the sheer volume and rushed nature of the productions meant that quality control was inconsistent. Audiences would witness both genuinely impressive athleticism and awkward, poorly executed sequences.

Production Values and Aesthetics: The Gritty Underbelly

Bruceploitation films were, almost without exception, products of a low-budget, high-turnover industry. This manifested in their aesthetics. Cinematography was often gritty, utilizing natural light and frequently shot on location in Hong Kong’s bustling streets or dilapidated warehouses. Sets were minimal, often existing merely to provide a backdrop for a fight. Sound design was a crucial element, often featuring excessively loud punching and kicking sounds, dramatic musical stingers, and, most notably, poor English dubbing. The voices rarely matched the actors, and the dialogue was frequently stilted, unintentionally comical, and full of non-sequiturs, further adding to the unique, often surreal, charm of these films.

Exploitation Beyond Lee:

While rooted in Bruce Lee’s legacy, some Bruceploitation films expanded their exploitative reach. Elements of blaxploitation were occasionally woven in, particularly in films aimed at the American market, sometimes featuring African American actors or characters to broaden appeal. Kung fu comedy, a burgeoning genre in Hong Kong at the time, also influenced some titles, injecting slapstick humor or more lighthearted fight sequences. A few even dabbled in horror or supernatural themes, demonstrating the genre’s willingness to throw anything at the wall to see what stuck.

Key Figures and Their Contributions: The Architects of Imitation

The success and proliferation of Bruceploitation relied on a cast of characters beyond just the “clones.”

The “Clones” and Their Careers:

As detailed, Bruce Li, Dragon Lee, and Bruce Le were the triumvirate of the Bruceploitation era. Bruce Li, after his extensive acting career as an imitator, eventually transitioned to directing, attempting to establish himself behind the camera, a testament to his ambition beyond mere mimicry. Dragon Lee continued to make martial arts films, often with a more aggressive, less theatrical approach, solidifying his niche. Bruce Le, despite his striking resemblance, often struggled to break out of the shadow of direct imitation, his films sometimes veering into the bizarre as he relentlessly pursued the Bruce Lee persona.

Directors and Producers: The Masterminds of the Mockery

Behind the cameras were figures like Joseph Lai and Godfrey Ho, two of the most prolific producers and directors of exploitation cinema in Hong Kong. They perfected the art of “cut and paste” filmmaking, often taking footage from multiple unfinished films, dubbing over them, and marketing them as new features. While not exclusively tied to Bruceploitation, their methods epitomized the genre’s rushed, commercially driven ethos. Their ability to churn out films at an astonishing rate ensured a constant supply of Bruceploitation titles, catering to an ever-hungry market. Other directors, like Lo Mar and Kuo Nan-Hong, also contributed significantly, often working with the same stable of actors and stunt performers.

Supporting Casts:

The films frequently featured familiar faces from the Hong Kong martial arts scene. Actors like Chang Yi, Carter Wong, Dolly Dots, and numerous stunt performers provided a sense of continuity and authenticity, lending credibility to the fight sequences even when the plots faltered. Their presence often highlighted the gulf between the leading “Bruce” and the more established kung fu practitioners, further emphasizing the imitative nature of the genre.

The Impact and Legacy of Bruceploitation: A Contested Canon

Bruceploitation’s legacy is complex, marked by both commercial success and critical disdain, cultural controversy and cult adoration.

Commercial Success and Critical Reception:

At the box office, particularly in international markets hungry for martial arts action, Bruceploitation films often performed surprisingly well. They were cheap to produce and filled a demand, especially in drive-in theaters, grindhouses, and burgeoning home video markets around the world. However, critical reception was overwhelmingly negative. Mainstream critics often dismissed the genre as cheap, uninspired, and disrespectful exploitation of a deceased icon. Serious film critics rarely engaged with these films, seeing them as beneath critical analysis.

Cultural Significance and Controversies:

The ethical dimensions of Bruceploitation were, and remain, a significant point of contention. The blatant commercial capitalization on Bruce Lee’s death was seen by many as disrespectful and tasteless. Fans who revered Lee often viewed these films as a grotesque perversion of his art and philosophy. The very term “Bruceploitation” itself carries a pejorative connotation, implying cynical exploitation.

However, despite these controversies, the genre served a peculiar cultural function. For many Western audiences, these films, however inferior, were their first exposure to Hong Kong martial arts cinema. They acted as a stepping stone, a gateway drug to the deeper, richer world of kung fu films, sometimes even leading viewers to discover the authentic works of Bruce Lee himself. They kept the image of “Bruce Lee,” however distorted, alive in popular culture.

Influence on Later Films and Pop Culture:

While rarely directly influencing major cinematic trends, Bruceploitation has achieved an enduring cult status. It is a frequent subject of discussion among martial arts film enthusiasts and B-movie aficionados. Filmmakers and artists occasionally reference the genre, often in a parodic or nostalgic context. Documentaries on Hong Kong cinema or exploitation films invariably dedicate segments to Bruceploitation, acknowledging its unique place in the industry’s history. Its over-the-top nature and often bizarre creativity have made it a source of ironic enjoyment for many.

Reappraisal and Academic Interest (as of 2025):

In recent years, there has been a growing academic interest in exploitation cinema as a whole, and Bruceploitation has not been immune to this reappraisal. Scholars are now examining the genre not merely as “bad cinema” but as a fascinating cultural artifact. They analyze:

- Media Consumption: What does the sustained demand for imitations reveal about audience psychology and media consumption habits in the wake of a celebrity’s death?

- Cultural Appropriation and Mimicry: How did these films navigate the line between homage and outright appropriation? What do they tell us about the nature of mimicry in popular culture?

- The Nature of Celebrity: How did Bruceploitation both capitalize on and contribute to the commodification of Bruce Lee’s image, even beyond his death?

- Global Cinema Studies: The genre’s global reach and its impact on the distribution and perception of Hong Kong cinema in various international markets.

This academic lens offers a more nuanced understanding, moving beyond simple dismissal to analyze Bruceploitation as a complex phenomenon reflecting the economic, social, and cultural forces at play during the 1970s and early 1980s.

Beyond the Imitation: What Bruceploitation Reveals

Stripping away the layers of imitation and controversy, Bruceploitation offers several profound insights into the nature of cinema, celebrity, and cultural hunger.

- The Unparalleled Power of an Icon: The sheer volume and persistence of Bruceploitation films underscore the unmatched impact Bruce Lee had on global culture. No other martial arts star, perhaps no other film star in such a short span, has inspired such a concerted and widespread effort at imitation. It cemented his status as a truly singular figure whose influence transcended his physical presence.

- The Mechanics of Exploitation Cinema: Bruceploitation serves as a textbook example of exploitation cinema at its most fundamental. It demonstrates how commercial pressures, combined with a lax approach to copyright and intellectual property, can lead to the rapid proliferation of a genre. It showcases the industry’s willingness to prioritize profit over artistic integrity or ethical considerations.

- The Global Reach of Martial Arts Cinema: Even the often-maligned Bruceploitation films played a role in the worldwide dissemination of kung fu cinema. They introduced martial arts to new audiences in diverse territories, paving the way for the later global success of genuine Hong Kong action films and influencing subsequent generations of action stars. They proved that there was a hungry global market for martial arts, regardless of the quality of the product.

Conclusion

Bruceploitation was, and remains, a bizarre, often cynical, yet undeniably influential chapter in martial arts film history. Born from the immediate aftermath of a global tragedy, it was a testament to both the enduring power of Bruce Lee’s image and the opportunistic nature of the film industry. While frequently dismissed as cheap imitations, these films, starring a revolving door of look-alikes, recycled tropes, and questionable production values, carved out their own unique niche.

Its mixed legacy is undeniable: a source of both genuine entertainment for a cult following and ethical questions regarding the exploitation of a deceased legend. Yet, as time offers new perspectives, Bruceploitation is increasingly seen not just as a cinematic anomaly, but as a fascinating cultural phenomenon. It highlights the profound impact of a singular icon, the ruthless mechanics of exploitation cinema, and the pervasive global hunger for martial arts action. The echo of the dragon’s roar, though sometimes distorted and off-key, continued to reverberate through these films, ensuring that Bruce Lee’s image, however transmuted, remained alive in the cinematic consciousness, forever cementing Bruceploitation’s place in the annals of film history.