The New Hollywood Cinema Movement, spanning roughly from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, represents one of the most transformative periods in American film history. This era witnessed a fundamental shift in how movies were made, who made them, and what stories they told, forever altering the landscape of cinema and establishing many of the artistic and commercial principles that continue to influence filmmaking today.

Origins and Historical Context

The movement emerged from a perfect storm of cultural, technological, and economic factors that converged in the 1960s. The old Hollywood studio system, which had dominated American cinema since the 1930s, was crumbling under the weight of changing audience tastes, television’s rise, and landmark antitrust decisions like the 1948 Paramount Decree. Audiences were abandoning theaters in droves, with annual admissions dropping from 4.7 billion in 1947 to just 2.1 billion by 1967.

The cultural upheaval of the 1960s—marked by the Vietnam War, civil rights movement, counterculture, and generational rebellion—created a hunger for films that reflected contemporary anxieties and challenges. Traditional Hollywood fare seemed increasingly irrelevant to younger audiences who had grown up with television and were influenced by European art cinema, particularly the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism.

The breaking point came with several high-profile studio failures in the early 1960s, including expensive musicals like “Doctor Dolittle” (1967) and “Hello, Dolly!” (1969), which lost millions of dollars. Studios began experimenting with younger filmmakers and more contemporary subjects as a matter of economic survival.

Key Characteristics and Innovations

New Hollywood filmmakers brought a radically different approach to cinema that challenged virtually every aspect of traditional moviemaking. Their films were characterized by moral ambiguity, where heroes were flawed and villains were complex human beings rather than one-dimensional archetypes. The clear-cut morality of classical Hollywood gave way to stories that reflected the confusion and cynicism of the era.

Stylistically, these directors embraced naturalistic performances, handheld cameras, location shooting, and improvisational techniques borrowed from European art cinema and documentary filmmaking. They favored gritty realism over studio polish, often shooting in actual locations rather than constructed sets. The visual language became more kinetic and experimental, with rapid editing, unconventional angles, and bold use of violence and sexuality.

Thematically, New Hollywood films explored previously taboo subjects including graphic violence, explicit sexuality, drug use, and corruption in American institutions. They questioned authority figures, examined the dark side of the American Dream, and often ended on ambiguous or pessimistic notes that would have been unthinkable in earlier Hollywood productions.

The Movie Brats: A New Generation of Auteurs

The movement was driven by a generation of film-school-educated directors who approached cinema as both art and entertainment. Francis Ford Coppola, who had studied at UCLA, emerged as an early leader with “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967), which he produced, revolutionizing screen violence and challenging censorship standards. His “The Godfather” (1972) and “The Godfather Part II” (1974) demonstrated that serious, artistic films could also be massive commercial successes.

Martin Scorsese brought an intensely personal, Catholic-influenced perspective to urban crime stories like “Mean Streets” (1973) and “Taxi Driver” (1976), combining documentary-style realism with operatic emotional intensity. His use of popular music, voice-over narration, and kinetic camera movement became hugely influential.

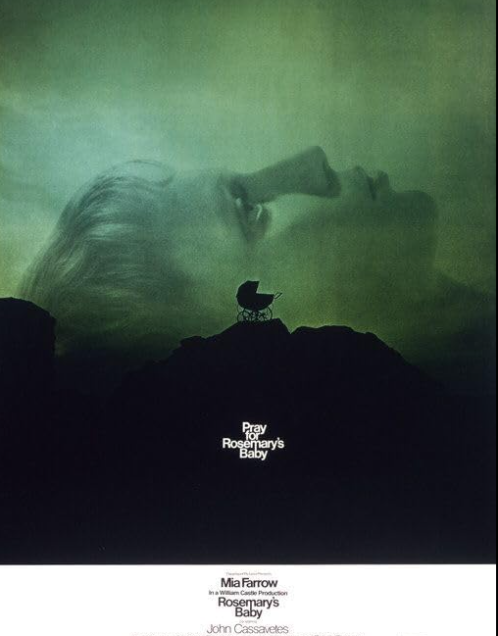

William Friedkin shocked audiences with “The French Connection” (1971) and “The Exorcist” (1973), films that pushed the boundaries of screen violence and horror while maintaining artistic credibility. Steven Spielberg, though often considered separate from the movement’s more pessimistic tendencies, revolutionized blockbuster filmmaking with “Jaws” (1975), creating the template for the modern summer movie.

George Lucas similarly straddled art and commerce, moving from the dystopian “THX 1138” (1971) to the nostalgic “American Graffiti” (1973) before creating the “Star Wars” phenomenon that would ironically contribute to New Hollywood’s decline.

Other significant figures included Robert Altman, whose overlapping dialogue and ensemble casts in films like “MAS*H” (1970) and “Nashville” (1975) created a distinctly American form of art cinema; Hal Ashby, who directed counterculture classics like “Harold and Maude” (1971) and “Being There” (1979); and Terrence Malick, whose poetic “Badlands” (1973) and “Days of Heaven” (1978) pushed cinematic lyricism to new heights.

Landmark Films and Their Impact

Several films stand as defining works of the movement, each breaking new ground in different ways. Arthur Penn’s “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967) is often cited as the movement’s breakthrough film, with its romanticized outlaws, shocking violence, and anti-establishment themes resonating with young audiences while horrifying traditional critics.

“The Graduate” (1967) captured generational alienation through Benjamin Braddock’s aimless rebellion against suburban conformity, while its innovative use of Simon and Garfunkel’s music demonstrated how popular songs could enhance narrative themes. Mike Nichols’ direction combined European art-film techniques with accessible storytelling.

Dennis Hopper’s “Easy Rider” (1969) became a cultural phenomenon despite its tiny budget, proving that independent films could find massive audiences. Its portrait of two hippie bikers traveling across America struck a chord with counterculture audiences and demonstrated the commercial potential of youth-oriented films.

“The Godfather” trilogy elevated genre filmmaking to high art, with Coppola creating an epic meditation on power, family, and American capitalism disguised as a crime saga. The films’ success proved that audiences would embrace complex, lengthy narratives if they were sufficiently compelling.

“Chinatown” (1974) represented the movement’s sophisticated peak, with Roman Polanski directing Robert Towne’s labyrinthine screenplay about corruption in 1930s Los Angeles. The film combined film noir traditions with contemporary cynicism, creating a perfect synthesis of classical Hollywood craftsmanship and New Hollywood themes.

Breaking Down Barriers: Content and Censorship

New Hollywood filmmakers played a crucial role in dismantling the restrictive Production Code that had governed film content since 1930. The establishment of the MPAA rating system in 1968 allowed filmmakers unprecedented freedom to explore mature themes and explicit content.

Films like “Midnight Cowboy” (1969), which won the Academy Award for Best Picture despite receiving an X rating, demonstrated that serious films could tackle controversial subjects like homosexuality and prostitution. “The Exorcist” pushed horror into genuinely disturbing territory, while “Taxi Driver” explored urban alienation and potential violence with unprecedented psychological depth.

This new freedom extended beyond violence and sexuality to include frank discussions of politics, religion, and social issues. Films routinely questioned American institutions, from government (“All the President’s Men,” 1976) to military (“Apocalypse Now,” 1979) to corporate power (“Network,” 1976).

The Business Revolution

New Hollywood also transformed the business side of filmmaking. The collapse of the studio system created opportunities for independent producers and smaller companies to compete with major studios. Films could be made more cheaply and quickly than traditional studio productions, often with profit participation deals that gave creative personnel financial stakes in their films’ success.

The success of films like “Easy Rider,” which cost $400,000 and earned over $60 million worldwide, proved that small-budget films could generate enormous profits. This encouraged studios to take chances on unconventional projects and unknown directors.

However, the movement also inadvertently contributed to the rise of the modern blockbuster. The massive success of “Jaws” and “Star Wars” demonstrated the profit potential of high-concept, effects-driven entertainment that could appeal to global audiences. This would ultimately contribute to New Hollywood’s decline as studios increasingly focused on franchise filmmaking.

International Influence and Recognition

New Hollywood films gained international acclaim and influenced filmmakers worldwide. European critics, who had long dismissed American cinema as commercially crude, began taking Hollywood seriously as an artistic medium. Directors like Coppola and Scorsese were celebrated at international film festivals, while American films began winning major prizes at Cannes and other prestigious venues.

The movement’s influence extended far beyond America, inspiring similar “new wave” movements in other countries and establishing American independent cinema as a legitimate alternative to both Hollywood commercialism and European art cinema.

Decline and Legacy

By the early 1980s, New Hollywood was effectively over, victim of its own success and changing industry dynamics. The enormous success of “Star Wars” and similar blockbusters convinced studios that safer, more commercial projects were preferable to the risky, personal films that had defined the movement.

Several high-profile failures, including Coppola’s “One from the Heart” (1982) and Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate” (1980), demonstrated the dangers of giving directors unlimited creative and financial control. Studios began reasserting control over production, leading to more conventional, market-tested filmmaking.

The rise of home video, cable television, and later digital technology fundamentally changed how films were distributed and consumed, making the theatrical experience less central to film culture. The consolidation of theater chains and the rise of multiplex cinemas favored broadly appealing films over challenging, artistic works.

Enduring Impact on Contemporary Cinema

Despite its relatively brief lifespan, New Hollywood’s influence on contemporary cinema cannot be overstated. The movement established the modern conception of the director as auteur, creative visionary, and celebrity figure. Directors like Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson, and the Coen Brothers clearly draw inspiration from New Hollywood’s combination of artistic ambition and popular appeal.

The movement’s emphasis on character-driven narratives, moral ambiguity, and stylistic innovation continues to influence serious filmmaking. Independent cinema, from the Sundance movement of the 1990s to contemporary streaming platforms, operates on principles established during the New Hollywood era.

Many of New Hollywood’s technical and aesthetic innovations became standard practice. Handheld camera work, natural lighting, location shooting, and improvisational acting techniques are now commonplace in both independent and mainstream filmmaking.

The movement also established many of the financial and distribution models that continue to shape the industry. The concept of profit participation, independent production deals, and filmmaker-friendly contracts originated during this period.

Conclusion

The New Hollywood Cinema Movement represents a unique moment when artistic ambition, cultural relevance, and commercial success converged to create a body of work that redefined American cinema. While the movement itself was relatively brief, its impact continues to reverberate through contemporary filmmaking.

The directors who emerged during this period created films that were simultaneously of their time and timeless, addressing specific cultural moments while exploring universal themes of power, corruption, alienation, and identity. Their work demonstrated that American cinema could be both popular entertainment and serious art, a lesson that continues to inspire filmmakers today.

Understanding New Hollywood is essential to understanding not just film history, but American culture in the late 20th century. These films captured a nation in transition, questioning its values and institutions while creating new forms of artistic expression. In doing so, they established cinema as America’s most influential cultural export and created the foundation for the global film industry we know today.