Introduction: A Filmmaker Who Shaped the 20th Century

Sergey Eisenstein wasn’t just a film director—he was a seismic force in the development of cinema itself. Often called the “father of montage,” Eisenstein didn’t merely make films; he reshaped how we think about moving images, how we process emotion through editing, and how cinema could become a tool of political, intellectual, and spiritual transformation.

Emerging from the cultural and political whirlwind of post-revolutionary Russia, Eisenstein fused radical ideology with bold experimentation. His influence continues to echo across global cinema—from Hollywood blockbusters to avant-garde installations—making him one of the most essential figures in the history of the medium.

This article explores Eisenstein’s background, creative philosophy, pioneering editing techniques, iconic films, and his profound legacy as a theorist, teacher, and artist.

Early Life and Theatrical Roots

Sergey Mikhailovich Eisenstein was born on January 23, 1898, in Riga, then part of the Russian Empire. His upbringing was cultured but conflicted: his father was an engineer with strict Tsarist loyalties, while young Sergey gravitated toward revolutionary politics and art. This tension between structure and rebellion would later define his cinematic philosophy.

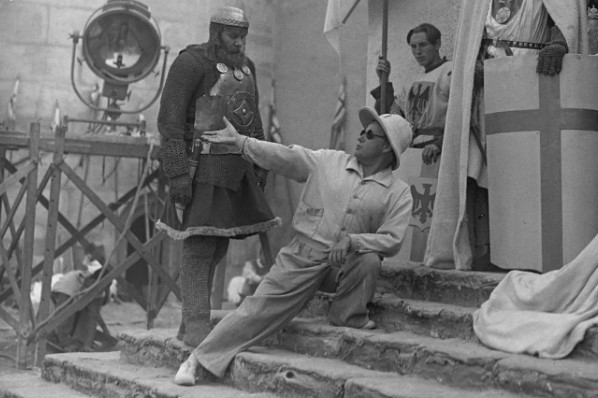

Initially trained in engineering, Eisenstein soon abandoned it for theater and art. He studied under Vsevolod Meyerhold, a leading figure in Russian experimental theater, who was developing a new physical style of acting known as “biomechanics.” Meyerhold’s emphasis on rhythm, gesture, and expressive movement would leave a deep imprint on Eisenstein’s approach to directing and visual storytelling.

Birth of a New Cinema: The Theory of Montage

What made Eisenstein truly revolutionary was not just his content, but his method. In the 1920s, Soviet cinema was being shaped by a group of theorists and filmmakers—Lev Kuleshov, Dziga Vertov, and Eisenstein among them—who believed cinema was a language, and editing was its grammar.

Eisenstein took this further. He proposed that the collision of shots—the dialectical clash of one image with another—could generate new meaning, beyond what each shot conveyed on its own. This became the foundation of his theory of “intellectual montage.”

For Eisenstein, montage was not merely a technical tool but a weapon. It could shape the viewer’s consciousness, provoke emotional responses, and engage audiences in ideological reflection. As he once wrote, “Montage is the nerve of cinema. To determine the nature of montage is to solve the specific problem of cinema.”

Strike (1925): A Bold Debut

Eisenstein’s first feature, Strike (Stachka, 1925), was an audacious experiment in collective storytelling. Rather than focusing on individual protagonists, the film presented the workers as a unified class struggling against oppression.

Filled with visual metaphors, cross-cutting, and dynamic compositions, Strike included the now-famous sequence where the brutal suppression of workers is intercut with the slaughter of a bull—a powerful montage meant to evoke visceral disgust and moral outrage.

It was clear from the start: Eisenstein was not making cinema for comfort. He was making cinema for revolution.

Battleship Potemkin (1925): A Cinematic Earthquake

Just months after Strike, Eisenstein released Battleship Potemkin, and nothing in world cinema would ever be the same.

Commissioned to commemorate the 1905 revolution, the film dramatized the mutiny of sailors against their Tsarist officers. Its most iconic sequence—the Odessa Steps massacre—remains one of the most studied and imitated scenes in film history. A baby carriage tumbling down a flight of stone steps amidst chaos has become a universal cinematic symbol, referenced in films like The Untouchables and Brazil.

But Eisenstein’s goal wasn’t realism—it was emotional manipulation through editing. He crafted rhythm, tempo, and visual conflict to evoke outrage, pity, and solidarity. The film’s influence on montage theory is unmatched. And despite being banned in several Western countries for its “subversive content,” Battleship Potemkin was hailed by critics like Georges Sadoul and Roger Ebert as one of the greatest films ever made.

October and Old and New: Montage Meets Marxism

Eisenstein’s next major works, October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928) and Old and New (1929), pushed montage to new heights—and sometimes to excess. October, made for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution, was a kaleidoscope of political symbolism. It juxtaposed images like a mechanical peacock with the provisional government, and a crucifix with Hindu idols, to critique religious hypocrisy and bourgeois vanity.

While visually stunning and philosophically bold, October also revealed the limits of montage as a didactic tool. The film’s dense symbolism could be confusing, even to politically sympathetic audiences. Still, it remains a crucial milestone in the fusion of art and ideology.

Old and New (also called The General Line) explored the modernization of agriculture, portraying the struggle between tradition and collective progress. Though less celebrated, the film includes some of Eisenstein’s most striking surrealist imagery, including an unforgettable sequence of cream churning as an erotic ritual of mechanized fertility.

Hollywood and Mexico: Dreams Deferred

In the early 1930s, Eisenstein was invited to Hollywood. He met with Charlie Chaplin, signed a contract with Paramount, and was given the green light to develop projects. But creative disagreements, particularly around censorship and artistic control, led to frustration.

Undeterred, Eisenstein headed to Mexico with the support of author Upton Sinclair to film ¡Que Viva México!, a sprawling epic about Mexican history and culture. However, budgetary issues and legal disputes halted the project. The footage was later reassembled posthumously by others, including Grigori Alexandrov, but the original vision remained incomplete.

The episode marked a personal and artistic disappointment. Eisenstein’s quest for cinematic freedom had run aground on the shoals of funding, politics, and compromise.

Stalin’s Shadow and the Soviet Shift

Upon returning to the USSR, Eisenstein faced a changing political landscape. Stalin’s regime was enforcing Socialist Realism as the official artistic doctrine, favoring accessible narratives and heroic figures over formalist experimentation. Eisenstein, once a golden child of revolutionary cinema, now found himself suspect for being too intellectual, too abstract, too “Western.”

His project Bezhin Meadow (1937) was shut down during production, with much of the footage destroyed. Only fragments and stills remain today, serving as a haunting reminder of both artistic ambition and state control.

The Ivan the Terrible Films: Art in a Cage

Eisenstein’s last major works, Ivan the Terrible Parts I (1944) and II (1946), commissioned by Stalin himself, tell the story of the 16th-century Tsar who unified Russia through ruthless power.

The first film was a triumph, winning Stalin’s approval and a Stalin Prize. It portrayed Ivan as a tortured genius, justified in his paranoia and brutality. But Part II, which delved deeper into Ivan’s descent into tyranny and paranoia, was banned by Stalin, who saw it as a dangerous allegory of his own rule. A planned Part III was never completed.

Artistically, the Ivan films were Eisenstein’s most expressionistic. He moved away from montage toward theatrical mise-en-scène, chiaroscuro lighting, elaborate costume, and even painted sets. It was a return to his roots in visual art and stagecraft, but filtered through years of experience, disappointment, and resilience.

Legacy: A Language for the Ages

Sergey Eisenstein died of a heart attack in 1948, at the age of 50. But his legacy is immortal.

His theories of montage became foundational texts in film schools worldwide. He wrote prolifically about cinema, leaving behind volumes of essays, lectures, and reflections. His ideas have influenced directors as varied as Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma, and Lars von Trier.

More than any single film, it is his philosophy that changed cinema: the belief that editing is not just a technical act, but a philosophical one. That juxtaposition can provoke thought. That cinema is not just storytelling—it is a machine for feeling, for awakening.

Human Side of a Giant

Despite his intellectualism, Eisenstein was not an aloof academic. He had a playful sense of humor, a love of caricature, and a lifelong fascination with art history and literature. He was a prolific sketch artist, often drawing grotesque cartoons of himself and others. He wrestled with personal identity, political compromise, and creative frustration—not as a god of cinema, but as a man trapped between genius and control.

His final years were spent more in the classroom than on the set. As a teacher at VGIK, he mentored a new generation of filmmakers and thinkers, ensuring that his ideas would not only survive, but evolve.

Conclusion: The Architect of Cinematic Thought

To study Sergey Eisenstein is not only to study a man, but to study cinema’s potential as a moral, emotional, and intellectual force. His life was filled with contradictions: revolutionary and state servant, radical artist and compromised realist, global visionary and political prisoner.

But through it all, Eisenstein remained committed to the idea that cinema could shape human consciousness. That it could elevate rather than distract. That it could transform the chaos of history into clarity—and sometimes, into beauty.

In our era of visual saturation, fast cuts, and endless content, Eisenstein’s work invites us to pause. To see. To feel. To think. That is his enduring gift.