Introduction: Shadows, Madness, and the Birth of Modern Cinema

In the dark corridors of early 20th-century cinema, few names shine — or rather, flicker — with as much enigmatic brilliance as Robert Wiene. A figure both celebrated and elusive, Wiene stands at the heart of German Expressionism, that short-lived yet eternally influential movement that transformed film from entertainment into psychological art. His masterpiece, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920), is not only one of the defining works of Weimar cinema, but also a cornerstone of film history — a movie that redefined visual storytelling, introduced modern psychological horror, and shaped the grammar of the cinematic dream.

Yet Wiene’s story, like his films, unfolds in chiaroscuro — light and shadow, brilliance and obscurity. His career both predates and transcends Caligari; his style reflects a restless experimentation typical of postwar Germany, where art mirrored the anxieties of a society grappling with trauma, instability, and moral disintegration. To understand Wiene is to explore not just a filmmaker but a cultural mirror of an era when madness became a metaphor for history itself.

This article examines Robert Wiene’s life, innovations, aesthetic philosophy, and legacy, situating him within the broader narrative of early cinema and the artistic turbulence of the Weimar Republic.

Early Life and Path to Cinema

Robert Wiene was born on April 27, 1873, in Breslau (then part of the German Empire, now Wrocław, Poland), into a family steeped in performance and art. His father, Karl Wiene, was a respected stage actor, and young Robert initially followed a more traditional academic path, studying law in Berlin and Vienna. But the magnetism of theater — and later film — proved irresistible.

Like many artists of his generation, Wiene entered cinema through the backdoor of theater, carrying with him a deep appreciation for stagecraft, gesture, and visual design. The outbreak of World War I and the subsequent collapse of the German Empire profoundly shaped his worldview. By the war’s end, Germany was a nation of ruins, inflation, and psychological exhaustion — a perfect incubator for the Expressionist vision of a world distorted by inner turmoil.

Wiene began directing in the 1910s, contributing to Germany’s rapidly growing silent film industry. Before his breakthrough, he worked on melodramas and literary adaptations, often exploring moral and psychological conflict. This preoccupation with the human mind under strain would later define his style and artistic identity.

The Weimar Context: Cinema in a Time of Crisis

To understand Wiene’s contribution, one must grasp the historical and artistic climate of postwar Germany. The Weimar Republic (1919–1933) was a paradox: politically unstable yet culturally fertile. It produced some of the most daring experiments in art, theater, and film. Economic depression and collective trauma turned introspection into a national art form.

Cinema became an outlet for the collective unconscious, and Expressionism emerged as its visual language. Unlike realism, Expressionism externalized inner states — fear, paranoia, alienation — through stylized sets, exaggerated lighting, and distorted perspectives. The movement was less about representing the world than projecting the psyche onto it.

This was the cinematic soil in which Wiene planted his greatest work.

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920): The Dream that Shook the World

The Birth of Expressionism on Film

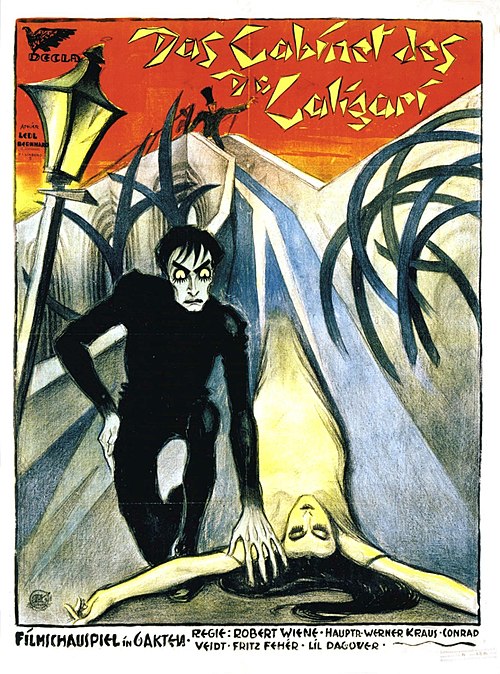

Released in 1920, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) was an earthquake. Directed by Robert Wiene and written by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer, the film tells the story of a hypnotist, Dr. Caligari, who uses a somnambulist named Cesare to commit murders. Told through a framing device that reveals the narrator’s insanity, the film blurs the boundaries between reality and delusion.

What set Caligari apart was not just its plot but its aesthetic audacity. The production design, by Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Röhrig, replaced realism with angular distortions — jagged streets, twisted architecture, painted shadows, and warped interiors. Everything in the film feels diseased, like a world infected by madness.

Wiene’s direction harnessed this surreal environment to create one of cinema’s first true psychological landscapes. The camera, still static by modern standards, functions as an observer within a nightmare. Faces emerge from darkness; gestures stretch beyond naturalism; reality itself becomes theatrical.

The Duality of Madness and Authority

At its core, Caligari is a political allegory — a warning about authoritarian control and psychological submission. Scholars have long debated its meanings. Some interpret Caligari as a symbol of tyrannical authority, Cesare as the obedient subject, and the narrative as a reflection of Germany’s descent into obedience and militarism. Others see it as a parable of postwar trauma — a nation haunted by guilt and anxiety, seeking control through repression.

Wiene, though not the author of the original screenplay, was crucial in realizing these themes visually. His insistence on the film’s framing device — the revelation that the story is told by an asylum inmate — adds layers of ambiguity. Is madness a personal condition or a societal one? Is Caligari the manipulator or the victim of delusion? Wiene transformed what might have been a straightforward horror tale into a meditation on subjective truth and the instability of perception.

Visual Language and Innovation

Caligari introduced visual concepts that would become the DNA of horror and noir cinema:

- Expressionist mise-en-scène: Every set element conveys psychological tension. Angles are hostile; lines converge unnaturally.

- Chiaroscuro lighting: Though lighting was painted rather than projected, the idea of symbolic light and shadow became central to German and later American cinematography.

- Symbolic acting: Conrad Veidt’s portrayal of Cesare — elongated, mechanical, yet tragic — became an icon of cinematic otherness.

- Framing and perspective: The film plays constantly with depth and flatness, immersing viewers in a dream that resists spatial logic.

These techniques were revolutionary. Before Caligari, film sets aimed to imitate reality. After Caligari, cinema learned that distortion could reveal truth.

Beyond Caligari: Wiene’s Search for Form and Meaning

Though history often defines Wiene by Caligari, his career extended well beyond that single triumph. In the 1920s, he directed a series of ambitious films exploring psychology, morality, and the uncanny — each demonstrating his commitment to visual experimentation and narrative complexity.

Genuine: A Tale of a Vampire (1920)

Released shortly after Caligari, Genuine revisited Expressionist aesthetics with even greater stylization. The film tells of a mysterious woman, a priestess enslaved and then worshiped by men who fall under her spell. Like Caligari, it features twisted sets and heightened gestures, but this time Wiene focused on erotic obsession and fatal desire.

Though less successful commercially, Genuine deepened Wiene’s reputation as a visual innovator. The film’s set design — fluid, dreamlike, filled with biomorphic curves — anticipated Surrealist cinema and later works like Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet.

Raskolnikow (1923)

Wiene’s adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (Raskolnikow) demonstrated his transition from overt Expressionism toward psychological realism. The film retains stylized lighting and exaggerated shadows but grounds them in a narrative of moral guilt.

Here Wiene shows his thematic evolution: from externalizing madness to exploring interior consciousness. His portrayal of Raskolnikow’s torment echoes Weimar society’s struggle with postwar guilt. The sets still hint at Expressionism but are subtler, reflecting Wiene’s growing command over tone and atmosphere.

The Hands of Orlac (1924)

Perhaps Wiene’s second most famous film, Orlacs Hände (The Hands of Orlac) fused horror, psychology, and science fiction. Based on the novel by Maurice Renard, it stars Conrad Veidt as a pianist who loses his hands in an accident and receives transplanted hands from a murderer. Tormented by the belief that the hands compel him to kill, Orlac becomes a tragic symbol of the fractured modern self.

The Hands of Orlac is a masterpiece of psychological horror and one of the earliest explorations of body identity and alienation — themes that would dominate later films like Frankenstein (1931) and Eyes Without a Face (1960). Wiene’s careful balance of suspense and introspection shows his mastery of tone: every gesture, every shadow feels imbued with dread. The film also prefigures the mad scientist trope that became central to genre cinema.

The Other Works: Experimentation and Decline

Throughout the 1920s, Wiene continued to experiment. Films such as Fear (1917), The Night of Decision (1920), and The Queen of Moulin Rouge (1926) showcased his versatility. His subjects ranged from social melodrama to light comedy, though his Expressionist legacy often overshadowed these efforts.

By the late 1920s, Wiene’s style appeared increasingly out of step with the new realism emerging in German cinema, represented by G. W. Pabst and the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement. Yet even as tastes shifted, Wiene remained committed to exploring psychological depth through form.

Wiene’s Style: The Architecture of Anxiety

Robert Wiene’s cinematic style is difficult to categorize because it bridges multiple artistic philosophies. His films fuse theatricality with cinematic experimentation, creating a visual grammar that conveys emotion rather than logic.

1. Expression as Structure

Unlike naturalistic directors, Wiene used form to express emotion. In Caligari, architecture becomes psychology; in Orlac, lighting becomes guilt. Every line, prop, and gesture carries meaning. His sets are not backgrounds but extensions of the human mind.

2. Theater and the Frame

Wiene’s roots in theater shaped his approach to framing. His actors move within a clearly delimited stage-like space, yet he uses depth and perspective distortion to escape theatrical flatness. This tension — between confinement and movement — mirrors the characters’ mental states.

3. The Psychological Close-Up

Though not as kinetically experimental as Eisenstein or Vertov, Wiene mastered the psychological close-up. In Orlac, the trembling of hands or the widening of eyes becomes as expressive as entire monologues. He believed that cinema’s true power lay not in spectacle but in capturing interior states through gesture and gaze.

4. Atmosphere of Unease

Wiene’s lighting design often emphasizes ambiguity rather than contrast. Shadows don’t merely hide but threaten to reveal. His worlds feel airless, confined, and fragile — reflections of Weimar anxiety. This approach anticipated the film noir aesthetic of the 1940s, where paranoia and guilt became visual motifs.

The Coming of Sound and the Fall into Exile

The arrival of sound cinema in the late 1920s challenged many silent-era directors, and Wiene was no exception. His first sound film, Der Andere (The Other, 1930), explored the theme of split identity, foreshadowing later psychological thrillers. It tells the story of a lawyer suffering from dual personality — a continuation of Wiene’s obsession with the divided self.

However, the rise of Nazism soon forced Wiene, who was of Jewish heritage, to flee Germany. Like many Weimar artists — from Fritz Lang to Billy Wilder — he became part of the exiled generation whose creativity was scattered by tyranny. He moved first to Austria, then to France, continuing to direct under increasingly difficult conditions.

In 1938, while preparing a French remake of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Wiene fell ill and died in Paris at age 65, just before the film’s completion. His death marked the symbolic end of the Expressionist era he had helped create.

Thematic Analysis: Madness, Control, and the Fragmented Self

Across his body of work, several recurring themes define Wiene’s vision:

1. Madness as Mirror

For Wiene, insanity was not pathology but metaphor. His characters — Cesare, Caligari, Orlac, Raskolnikow — all reflect inner fragmentation and societal decay. Madness becomes a lens through which to examine moral collapse and alienation.

2. The Duality of Man

From Caligari to Der Andere, Wiene’s protagonists struggle with divided selves — reason versus impulse, morality versus desire. This obsession mirrors the collective schizophrenia of Weimar Germany: a nation caught between democracy and authoritarianism, progress and despair.

3. The Fear of Control

Authority figures in Wiene’s films — doctors, priests, fathers — often embody manipulation. They wield power through hypnosis, surgery, or ideology. His work anticipates later explorations of totalitarian control and psychological domination, from 1984 to The Manchurian Candidate.

4. The Body as Battlefield

In The Hands of Orlac, Wiene explores the terror of bodily transformation — a theme that prefigures modern horror’s fascination with identity and flesh. The body becomes the site of moral and existential struggle, haunted by memory and guilt.

Wiene’s Contribution to Film History

Robert Wiene’s place in cinema history is both secure and underappreciated. While The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari stands as his undeniable masterpiece, his broader contribution lies in establishing film as a medium of psychological and philosophical inquiry.

- He pioneered the idea of subjective cinema — films that reflect interior consciousness rather than external events.

- He fused visual design with narrative meaning, influencing generations of filmmakers from Alfred Hitchcock to Tim Burton.

- He brought Expressionism to the screen, translating the artistic innovations of painting and theater into cinematic language.

- He helped define horror as a serious art form, where fear arises not from monsters but from the instability of perception.

Without Wiene, the lineage from Caligari to Psycho, The Shining, and Mulholland Drive would be incomplete.

Influence and Legacy

Influence on Weimar and Beyond

Wiene’s visual daring inspired contemporaries like Fritz Lang (Metropolis, M) and F. W. Murnau (Nosferatu, Faust). His success with Caligari proved that abstract art could reach popular audiences. The film’s box-office triumph opened doors for studios to fund experimental projects, helping to create the golden age of Weimar cinema.

The Seeds of Horror and Film Noir

Caligari’s expressionist lighting and psychological horror laid the groundwork for Universal’s monster films of the 1930s and the film noir aesthetic of the 1940s. Directors like James Whale, Robert Siodmak, and Fritz Lang (in exile) carried Wiene’s shadow play into Hollywood, merging German Expressionism with American genre cinema.

Psychological Cinema and Modernism

Wiene’s interest in perception and subjectivity influenced the evolution of modernist cinema. Films such as Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf, Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, and David Lynch’s Eraserhead echo Wiene’s exploration of disturbed minds and distorted spaces.

Aesthetic Legacy

Today, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari remains a staple of film studies curricula worldwide. It continues to influence visual artists, stage designers, and directors exploring the intersection of architecture and psychology. Its hand-painted shadows have become synonymous with the birth of cinematic expressionism — an art where the world looks the way fear feels.

The Rediscovery of Wiene: From Forgotten Master to Canonical Figure

For decades after his death, Robert Wiene’s reputation languished in the shadow of Caligari itself. Many of his other films were lost, neglected, or misattributed. It was only in the latter half of the 20th century that film scholars began to reassess his oeuvre and recognize his broader contributions.

Restorations of Raskolnikow and The Hands of Orlac have revealed a filmmaker of subtlety and philosophical depth, not merely a stylist. Modern criticism now sees Wiene as a bridge between theatrical expressionism and cinematic modernism, a craftsman who turned the silent screen into a canvas for the subconscious.

In 2014, a digitally restored Caligari premiered at the Berlinale, stunning audiences anew with its clarity and design. A century after its release, its angular shadows still feel prophetic — a nightmare that never ends.

Why Wiene Matters Today

In an age dominated by digital perfection and cinematic realism, Wiene’s work reminds us of film’s metaphoric power. His distorted sets and unreal lighting express emotions more vividly than any naturalistic image could. His films argue that truth in art lies not in imitation but in transformation.

Moreover, the anxieties haunting Weimar Germany — manipulation, mass psychology, fractured identity — echo eerily in our modern world. The hypnotic Dr. Caligari, commanding obedience from a sleepwalking populace, feels disturbingly relevant in an age of propaganda, surveillance, and social control.

To watch The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari today is to see not only the birth of cinematic modernism but a mirror of our own fragmented times.

Conclusion: The Dream That Never Ended

Robert Wiene’s cinema emerged from a world unhinged by war and uncertainty, and he transformed that instability into art. His films taught audiences to look inward — to see the shadows of the mind projected onto the screen.

Through The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, he gave cinema its first true dream, its first psychological architecture, its first glimpse of the unconscious. Through The Hands of Orlac, he gave horror its soul — the terror of not knowing where the self ends and the other begins.

He may not have lived to see the enduring power of his vision, but his influence continues to ripple through the art of film, theater, and design. Every tilted camera angle, every stylized nightmare, every psychological labyrinth owes a debt to Robert Wiene — the man who turned madness into a visual language.

As the credits roll on the silent flicker of Caligari, we realize that Wiene’s cinema was never merely about insanity or horror. It was about the fragile beauty of human perception — and the terrifying realization that reality itself might just be another painted backdrop.