Introduction: From Ruins to Revelation

The Second World War did not merely destroy nations—it dismantled the very foundations of modern civilization. The conflict’s physical and moral devastation left Europe in a state of existential exhaustion, and cinema, as the most expressive art form of the 20th century, became a vessel for rediscovering meaning amid the ruins. In the aftermath, a new generation of filmmakers rejected the artificiality of prewar studio systems and sought instead to confront the raw texture of life itself. The 1940s to 1960s thus marked a crucial transition in world cinema—from illusion to authenticity, from myth to self-awareness.

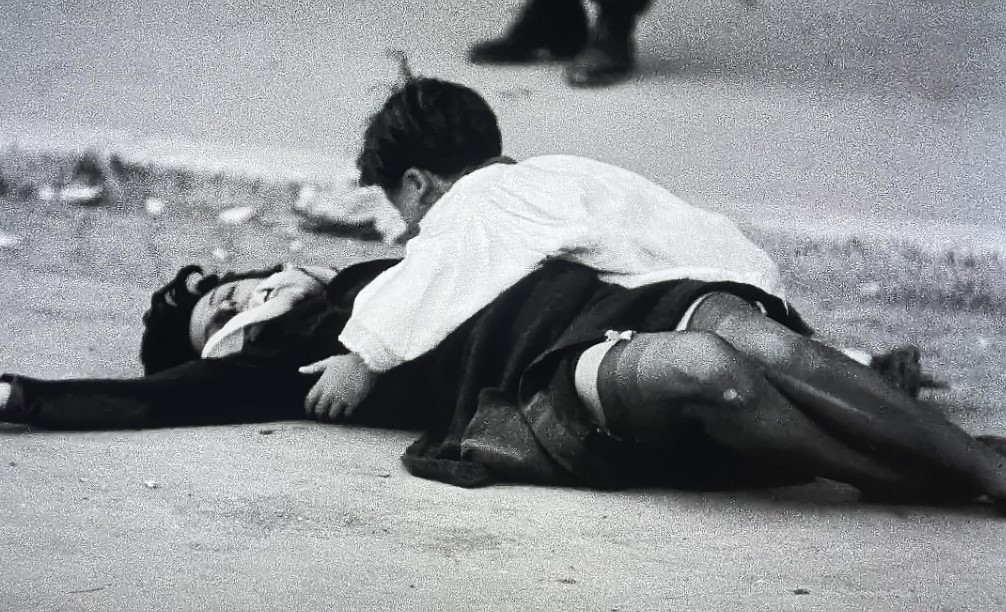

Across the continent, directors no longer aspired to entertain or console; they sought to bear witness. They placed their cameras among the poor, the disillusioned, and the marginalized, making art not of escapism but of compassion and critique. Italian Neorealism redefined cinematic truth; the French New Wave exploded formal conventions; British and Eastern European filmmakers exposed the alienation and hypocrisies of modern society; and in Japan, directors transformed national trauma into humanist reflection.

This essay traces, chronologically, the evolution of this cinematic modernism—from the moral realism of the 1940s to the self-reflexive artistry of the 1960s—revealing how postwar cinema reimagined humanism in an age when faith in humanity seemed lost.

I. The 1940s: The Birth of Postwar Realism

The 1940s witnessed the birth of a cinema grounded in necessity and morality. With cities bombed, studios destroyed, and resources scarce, filmmakers turned to the streets and real people as their subjects. Out of this deprivation arose one of the most influential movements in film history: Italian Neorealism.

Italian Neorealism: Rossellini, De Sica, and the Ethics of Reality

Italian Neorealism was more than an aesthetic; it was a worldview forged from crisis. Emerging in the final years of World War II, it rejected the glossy artificiality of Fascist-era cinema—films that had ignored the hardships of ordinary Italians. The neorealists sought to capture truth through direct observation.

Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) is widely seen as the birth of this new cinema. Made amid the chaos of occupied Rome, it blurred the boundary between documentary and fiction. The film’s ragged immediacy, handheld camerawork, and emotional realism resonated as both reportage and resistance. Its moral force lay in its refusal to aestheticize suffering; it treated ordinary people not as victims but as witnesses to history.

Rossellini’s later works, Paisà (1946) and Germany Year Zero (1948), expanded this perspective beyond Italy’s borders, portraying postwar Europe as a shared moral landscape. His realism was spiritual rather than political—an attempt to restore dignity and moral coherence through film.

Vittorio De Sica, working with screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, gave Neorealism its humanist heart. Bicycle Thieves (1948) distilled the movement’s ethos into a story of everyday struggle—a man’s desperate search for his stolen bicycle becomes a modern parable of dignity, labor, and paternal love. The film’s simplicity, coupled with its documentary-like attention to urban space, epitomized Zavattini’s call for a “cinema of reality.”

In Umberto D. (1952), De Sica stripped away even the minimal plot of Bicycle Thieves, focusing instead on the daily humiliation of an elderly pensioner. The film’s quiet despair revealed the growing alienation of modern life, bridging Neorealism’s social realism with existential modernism.

Aesthetically, Neorealism rejected cinematic illusion. It favored nonprofessional actors, on-location shooting, natural light, and long takes—techniques that served both ethical and aesthetic goals. This commitment to authenticity was revolutionary because it restored cinema’s moral responsibility: to show life as it is.

Neorealism’s influence reached far beyond Italy. It inspired postwar realism in Britain, France, and Eastern Europe, and shaped filmmakers from Satyajit Ray in India to Kurosawa in Japan. But above all, it laid the moral and stylistic groundwork for the next phase of European cinema—modernism, which would turn realism inward, transforming it into an exploration of consciousness.

II. The 1950s: The Modernist Turn

By the mid-1950s, Europe had begun to rebuild. Prosperity returned to parts of the continent, but with it came a pervasive sense of spiritual emptiness. The horrors of war had left deep psychological wounds, and the rise of consumerism and mass media produced a new alienation. Cinema responded by turning its lens not outward toward society, but inward toward the self. This was the era of cinematic modernism—and at its forefront stood France.

The French New Wave: Godard, Truffaut, and Resnais

The French New Wave emerged from the critical culture of Cahiers du Cinéma, a magazine founded in 1951 by André Bazin and others who believed cinema could be as expressive as literature or painting. Young critics like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Éric Rohmer absorbed Bazin’s realist philosophy but fused it with their own existential and aesthetic radicalism. They were the first true cinephile generation—critics turned auteurs, armed with theory, curiosity, and portable cameras.

Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) inaugurated the movement. Its portrayal of adolescent rebellion was both personal and universal, merging Neorealism’s authenticity with lyrical subjectivity. The film’s mobile camera, natural lighting, and open-ended structure rejected the rigidity of traditional French cinema.

That same year, Jean-Luc Godard released Breathless (À bout de souffle), a film that shattered cinematic grammar. Its jump cuts, improvised dialogue, and self-referential irony turned filmmaking into an act of rebellion. Godard’s cinema was political in form as much as in content; it embodied freedom through its very fragmentation. His characters were antiheroes, navigating an absurd, media-saturated world—a reflection of postwar Europe’s existential crisis.

Alain Resnais took this modernism even further. In Hiroshima mon amour (1959), he blended documentary realism with poetic abstraction, exploring the limits of memory and trauma. The film’s nonlinear structure mirrored the fractured consciousness of a post-nuclear world. Last Year at Marienbad (1961) went deeper still, dissolving time and narrative into pure cinematic consciousness.

Philosophically, the French New Wave was shaped by existentialism and phenomenology—the belief that reality is subjective and perception itself is unstable. The modernist filmmaker became not a storyteller but a philosopher, using cinema to question the nature of experience.

While Italian Neorealism sought moral truth through compassion, the French New Wave sought intellectual truth through ambiguity. Its revolution was not just thematic but formal, breaking down the invisible walls of narrative cinema. Every cut, every silence, every shot became a statement about perception and freedom.

By the end of the 1950s, cinema had entered a self-aware phase. It no longer merely represented reality—it questioned it.

III. The 1950s–1960s: Social Realism and Political Reflection in Britain and the East

The British Free Cinema: Realism and Revolt

Postwar Britain was a nation caught between the fading empire and the rise of a new working-class identity. Against this backdrop, the Free Cinema movement emerged in the mid-1950s as a moral and aesthetic rebellion. Led by Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, and Tony Richardson, these filmmakers rejected the polite, middle-class narratives that dominated British screens and declared, “No film can be too personal.”

Their early documentaries—Anderson’s O Dreamland (1953), Reisz’s Momma Don’t Allow (1956), and Richardson’s Nice Time (1957)—were raw portraits of ordinary people, shot on 16mm film with handheld cameras. The movement’s spirit was both political and poetic: to show the “poetry of the everyday.”

By the late 1950s, Free Cinema evolved into Kitchen Sink Realism, a wave of social dramas depicting working-class life with unvarnished honesty. Films like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and A Taste of Honey (1961) portrayed disillusioned youth, class resentment, and the contradictions of modern Britain.

Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963) stands as a culmination of this movement. Its gritty realism and psychological intensity echoed Neorealism’s humanism but also reflected the existential malaise of the era. Anderson’s later works, such as If…. (1968), would take this critique to an allegorical extreme, merging realism with surrealist rebellion.

The Free Cinema’s importance lies in its moral stance. It democratized British cinema, made social inequality visible, and bridged the gap between documentary realism and personal expression—a connection that linked it to broader European modernism.

The Eastern Bloc: Andrzej Wajda and the Politics of Memory

In Eastern Europe, the struggle was not only artistic but ideological. Under Stalinist regimes, filmmakers faced censorship, yet many found ways to subvert official narratives through symbolism and allegory. Among them, Andrzej Wajda became a towering figure.

Wajda’s “War Trilogy”—A Generation (1955), Kanal (1957), and Ashes and Diamonds (1958)—portrayed the Polish experience of war with emotional and moral depth. Kanal’s depiction of fighters trapped in the Warsaw sewers offered a haunting metaphor for existential despair. Ashes and Diamonds, meanwhile, captured the confusion of a young generation facing political betrayal. The film’s final image—a dying hero writhing in a garbage heap—became a symbol of postwar Europe’s lost ideals.

Beyond Wajda, other Eastern European filmmakers—Milos Forman, Andrzej Munk, Miklós Jancsó, and Jiri Menzel—embraced a similar blend of realism and absurdism. The Czech New Wave of the 1960s turned this into a full-fledged movement, blending irony, satire, and documentary realism to critique authoritarianism.

These films represented a unique moral modernism, balancing truth and survival. Their realism was an act of resistance, their artistry an assertion of freedom. The East thus joined the West in transforming cinema into a mirror of conscience.

IV. The Global Reflection: The Japanese Renaissance

While European modernism reshaped Western cinematic thought, Japan experienced its own renaissance—a parallel exploration of realism, spirituality, and modernity that echoed yet transcended European influence.

Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, and Ozu: Three Paths to Human Truth

Akira Kurosawa was the most Westernized of the trio, yet his cinema spoke a universal moral language. Rashomon (1950) revolutionized narrative structure through its multiple perspectives, revealing the relativity of truth. Ikiru (1952) presented the bureaucratic modern world as a void redeemed only through compassion. Kurosawa’s use of movement, weather, and composition gave emotional resonance to moral struggle, embodying the postwar humanist ideal that dignity persists amid despair.

Kenji Mizoguchi, by contrast, turned to history and myth to critique the present. His Ugetsu (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954) wove realism with supernatural allegory, exploring the oppression of women and the cruelty of power. His graceful long takes and painterly framing imbued suffering with tragic beauty.

Yasujirō Ozu represented yet another approach: introspective minimalism. His Tokyo Story (1953) and Late Autumn (1960) observed domestic life with quiet precision. Through static compositions and ellipses, Ozu conveyed the impermanence of existence and the erosion of traditional values in modern Japan.

Together, these filmmakers formed the Japanese Renaissance, which paralleled European Modernism but was rooted in Buddhist and Confucian ethics. Where European directors dissected alienation, the Japanese sought harmony within transience. Their humanism was meditative rather than rebellious, showing that realism could lead not only to critique but also to compassion.

The global recognition of these works—culminating in Kurosawa’s success at Venice and Cannes—proved that the modernist impulse was universal. It reflected a shared postwar condition: the struggle to find meaning after catastrophe.

V. The 1960s: The Cinema of Consciousness

By the 1960s, realism and modernism had converged into a cinema that turned its gaze upon itself. The question was no longer what is real? but what is cinema?

In France, Godard became the most radical of the New Wave auteurs. Films like Pierrot le Fou (1965) and Weekend (1967) transformed cinema into political philosophy. He abandoned narrative coherence for collage-like montages that exposed consumerism and ideological decay. The camera became a tool of thought—challenging viewers to question not just society but the very act of representation.

In Italy, Michelangelo Antonioni carried modernism into existential territory. His “trilogy of alienation”—L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L’Eclisse (1962)—explored the emotional void of modern bourgeois life. His long takes and minimalist dialogue created a new cinematic language of absence. Where Neorealism sought human connection, Antonioni explored its disappearance.

Federico Fellini, once a disciple of Neorealism, turned inward. In La Dolce Vita (1960) and 8½ (1963), he fused realism with surrealism, memory with dream. Fellini’s cinema became autobiographical mythology—an act of self-examination that defined modernism’s ultimate evolution: the transformation of art into introspection.

Elsewhere, directors like Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Pier Paolo Pasolini extended this lineage into metaphysical realms. Bergman explored faith and isolation; Tarkovsky transformed realism into spirituality; Pasolini fused Marxism with myth. All were heirs to the postwar project of finding meaning through art when meaning itself seemed lost.

The 1960s thus marked the culmination of cinematic modernism: a period in which cinema ceased to be mere entertainment and became a mode of consciousness.

Conclusion: Humanism Reimagined

From the bombed streets of Rome to the neon-lit boulevards of Paris, from the gray industrial towns of England to the misty villages of Japan, the cinema of the 1940s–1960s charted humanity’s journey from despair to reflection. These decades redefined film not as illusion but as inquiry—an art form capable of revealing moral and emotional truth.

Italian Neorealism gave birth to cinematic ethics, proving that simplicity could contain universality. The French New Wave turned that ethical realism into philosophical exploration, inventing a language for modern subjectivity. British and Eastern European cinemas brought politics and class consciousness into the frame, while Japanese masters deepened the moral resonance of realism through spiritual contemplation.

Together, they forged a global modernism—a cinema of compassion and critique, of realism and reflection. What united them was not style but conviction: that art, even in times of darkness, could restore humanity’s moral vision.

By the close of the 1960s, cinema had entered its age of self-awareness. The seeds planted by Rossellini, De Sica, Godard, and Kurosawa would blossom in the works of Bergman, Tarkovsky, and countless others. The dialogue between realism and modernism—between outer truth and inner vision—continues to shape cinema today.

In this period, filmmakers did not simply record the postwar world—they reconstructed human consciousness itself, using the camera as both witness and philosopher. The result was one of the greatest intellectual and artistic revolutions in modern art: the transformation of film into a mirror of the modern soul.