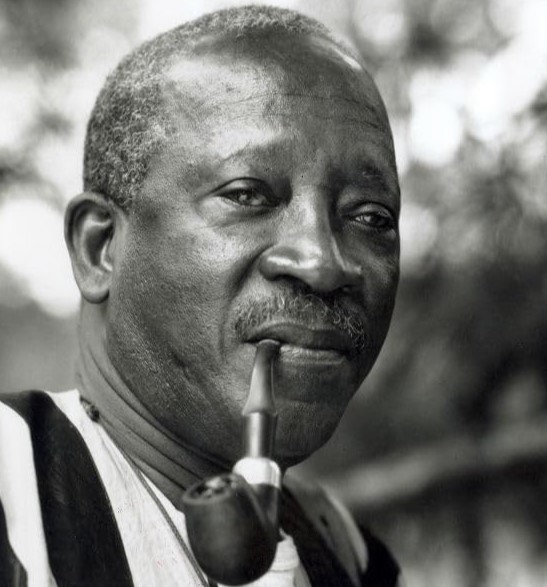

To cinephiles, Ousmane Sembène is not simply a director; he is an entire movement—an intellectual insurgent who transformed the screen into a tool of resistance, consciousness, and social transformation. He is often called “the father of African cinema.” His films are not decorative, not influenced by trends or aesthetics imported from elsewhere, and not interested in cinema as escapism. Instead, they function as militant narratives designed to awaken, provoke, irritate, illuminate, and inspire.

Writing about Sembène as a cinephile familiar with African cinema means acknowledging not just his films, but the world they fought against: colonial censorship, illiteracy, state repression, religious manipulation, gender inequality, and the systematic silencing of African voices. His cinema was forged in struggle and aimed to shatter the structures that continued to define post-independence Africa.

In a global landscape where African stories were long filtered through outsiders, Sembène insisted—sometimes gently, often ferociously—that Africans would speak for themselves. He rejected the idea that African cinema needed European validation. He refused to exoticize his community for foreign audiences. And he consistently placed ordinary people—workers, women, villagers—at the center of his narratives. He believed they were the true engines of African history.

To understand Sembène is to understand the profound idea that cinema, in the right hands, can be a weapon. This essay examines his life, artistic philosophy, major works, and eternal legacy, showing why Sembène remains one of the most essential storytellers not only of Africa, but of world cinema.

1. The Making of a Revolutionary Artist

From Casamance to Marseille: Life as a Worker, Thinker, and Fighter

Sembène’s origins shaped his worldview. Born in 1923 in Ziguinchor, Senegal, he grew up in a working-class family, absorbing oral storytelling traditions that would later define the cadence of his cinema. His early expulsion from school pushed him into the workforce—first as a fisherman, then as a construction laborer, and later as a manual worker in French factories.

This period in Marseille changed everything. There, Sembène witnessed class struggle firsthand. He became active in trade unions and joined the French Communist Party, aligning himself with workers’ rights and anti-imperialist movements. These political convictions became inseparable from his storytelling style. Even when his films deal with intimate characters or domestic conflict, they pulse with a broader sociopolitical awareness.

The Shift from Literature to Cinema

Before becoming a filmmaker, Sembène was already a major literary figure. His novels—“God’s Bits of Wood,” “The Black Docker,” and “Xala”—were powerful indictments of colonialism and the betrayals of newly independent African elites.

But Sembène recognized a crucial problem: only a small segment of the population could read. Literature, as he put it, could not reach the masses.

Cinema, however, could.

His motivation for transitioning into filmmaking was profoundly democratic: he wanted to speak to everyday Africans, including those who could not read his books. Cinema allowed him to bypass colonial linguistic barriers by using Wolof and other African languages. It allowed him to break through illiteracy by communicating through images and sound.

As he famously said:

“Africa must assume the responsibility of telling its own stories.”

2. The Birth of African Cinema: Sembène’s Early Films

Borom Sarret (1963): The First Film of Sub-Saharan Africa

At just over 20 minutes, “Borom Sarret” is a cinematic revolution compressed into a short. Sembène captures a day in the life of a Dakar cart driver, exposing the disparities between colonial leftovers and modern African realities. The protagonist struggles to survive, maneuvering between the wealthy Europeanized city and the impoverished Medina.

The film’s structure, simple yet devastating, becomes a template for Sembène’s early cinema:

- a worker as protagonist

- the city as a site of inequality

- neocolonial power structures haunting daily life

- a tone blending realism with sharp social critique

“Borom Sarret” set the foundation for African cinema not as ethnographic curiosity but as storytelling grounded in African experience.

Black Girl (1966): A Cinematic Earthquake

“Black Girl” (“La Noire de…”) is often the first Sembène film encountered by international cinephiles. Its boldness remains shocking even today.

The film follows Diouana, a young Senegalese woman who moves to France to work for a white family, only to face exploitation, racism, and isolation. The contrast between Diouana’s dreams and her brutal reality exposes the colonial illusion that Europe is a promised land.

Sembène’s camera is unflinching. He attacks the romanticization of French benevolence. He dismantles the postcolonial myth that independence cured the deep power imbalances between Europe and Africa. With its final scene—a masked child confronting the former employer—Sembène asserts that Africa sees, remembers, and will hold history accountable.

Mandabi (1968): Cinema in Wolof, Made for Africans

“Mandabi,” adapted from Sembène’s own novella, was groundbreaking as the first African film made in an African language. This gesture alone was politically radical. It allowed the film to be understood by Senegalese audiences in their own linguistic universe.

The plot revolves around a man who receives a money order from a nephew abroad. What seems like a simple gift becomes a critique of:

- bureaucracy inherited from colonial systems

- corruption

- greed

- male entitlement

- social pressure to maintain status

This film marks the moment Sembène fully embraced cinema as a weapon against injustice—not from a European art-house gaze, but from the everyday African perspective.

3. The Masterworks: Political Cinema at Its Most Courageous

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Sembène created some of the most important works in African film history. These films demonstrate his complete command over cinematic language and his fearless political voice.

Xala (1975): Post-Colonial Satire with Razor-Sharp Teeth

“Xala” is one of the great political satires of world cinema. Adapted from his own novel, it skewers the new African bourgeoisie—elite men who, after independence, simply inherited the power structures left behind by colonizers.

The plot centers around a wealthy businessman who becomes mysteriously impotent on the night of his third marriage. The impotence is symbolic: a punishment for betraying the people, for embracing corruption, and for abandoning the revolutionary spirit.

The film is playful, bitterly funny, visually vibrant, and politically explosive. It remains one of the clearest denunciations of post-independence hypocrisy ever captured on film.

Ceddo (1977): Conflict Between Islam, Christianity, and Tradition

“Ceddo” deepens Sembène’s critique beyond politics to include religion. Set in a precolonial village, the film explores the battle between traditional African customs, Islamic influence, and European missionaries.

The power struggles of the village reveal the ideological battles within Senegal itself.

“Ceddo” was banned for years in Senegal, officially for a spelling dispute but widely understood to be due to the film’s religious critique. Sembène accepted the censorship with defiance, arguing that African cinema must confront uncomfortable truths rather than avoid them.

Camp de Thiaroye (1988): A Devastating Anti-Colonial Epic

Co-directed with Thierno Faty Sow, “Camp de Thiaroye” revisits a shameful chapter of French colonial history: the massacre of African soldiers who fought for France in World War II and were then betrayed by the colonial government.

The film is one of Sembène’s most ambitious and heartbreaking. It exposes:

- racism within the French military

- the exploitation of African soldiers

- colonial hypocrisy in its purest form

- the psychological cost of fighting for an oppressor

Banned in France for years, this film solidified Sembène as not only an artist but a historical witness.

Guelwaar (1992): Postcolonial Identity and Social Conflict

“Guelwaar” marks Sembène’s return to contemporary Senegal. After a man’s death is mishandled, confusion erupts between Christian and Muslim communities over burial rights.

Through this apparently simple conflict, Sembène explores:

- religious coexistence

- dignity

- community responsibility

- political manipulation

- Western aid and dependency

The film’s tenderness and quiet humor contrast with its profound social critique.

4. Women at the Center: Sembène’s Feminist Lens

Although often labeled a political filmmaker, Sembène was equally a pioneer in feminist cinematic discourse. His portrayal of women stands apart in African film history—not as symbols, not as background figures, but as agents of resistance.

Faat Kiné (2000): Urban Womanhood in Modern Senegal

This film examines a successful businesswoman raising her children after being abandoned by their fathers. It defies stereotypes by presenting:

- a strong, economically independent African woman

- a critique of patriarchal norms

- the impact of modernization

- generational shifts in gender expectations

Sembène celebrates his protagonist not with sentimentality, but with a grounded realism that acknowledges both struggle and triumph.

Moolaadé (2004): The Summit of Sembène’s Feminist Cinema

“Moolaadé” is perhaps Sembène’s final masterpiece, a profound statement about gender, tradition, and resistance. The film revolves around a village woman who provides asylum to girls fleeing female genital mutilation (FGM). The community erupts in turmoil.

This film is breathtaking for many reasons:

- Its bravery in confronting taboo practices

- Its compassion for all sides of the debate

- Its portrayal of female solidarity

- Its indictment of male power structures

- Its political clarity, balanced with emotional warmth

The visual motif of the colored rope—marking the border of “moolaadé” or magical protection—becomes one of cinema’s great symbols of defiance.

With “Moolaadé,” Sembène proved that he remained a revolutionary voice until his final days.

5. Sembène’s Artistic Philosophy

Ousmane Sembène approached filmmaking with principles that set him apart from most directors of his era.

Cinema as a Weapon (But Also a Teacher)

For Sembène, cinema was not primarily entertainment. It was a political and educational instrument intended to raise consciousness. He used narrative clarity and simple structures to make his films accessible to rural populations.

African Languages at the Center

Sembène insisted on using Wolof, Diola, and other African languages to break from colonial linguistic imposition. This decision was part of his broader mission to reclaim African identity.

Critique from Within

Sembène criticized colonialism fiercely—but he was equally critical of African elites who perpetuated injustice. His moral compass was directed not by ideology but by human dignity.

Respect for Ordinary People

His protagonists were:

- cart drivers

- market women

- villagers

- soldiers

- young girls

By elevating everyday people, Sembène rejected elitism and redefined who could be a cinematic hero.

Cinema Rooted in Oral Tradition

Sembène described himself as a “modern griot.” His storytelling reflects oral structures—repetition, moral clarity, communal settings—while maintaining cinematic rigor.

6. Sembène’s Legacy: The Father of African Cinema

Ousmane Sembène’s impact is immeasurable.

1. He Founded Modern African Cinema

Before Sembène, African cinema was often dominated by outsiders. He proved that Africans could create films about their own lives and histories.

2. He Inspired Generations of Filmmakers

Directors such as Djibril Diop Mambéty, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, Abderrahmane Sissako, Alain Gomis, and Mati Diop all follow paths Sembène opened.

3. He Created a Model for Political Film

His work showed how cinema can fight injustice without losing emotional resonance.

4. He Elevated Women’s Voices

Through characters like Collé in “Moolaadé” and Faat Kiné, he emphasized women’s central role in African social transformation.

5. He Fought Censorship

Sembène never retreated before political or religious opposition. He believed truth required courage.

6. He Left a Cultural Blueprint

Sembène not only made films—he helped shape Africa’s modern cultural awareness.

7. Conclusion: Ousmane Sembène, Eternal Griot of Justice

To watch Ousmane Sembène’s films is to encounter:

- history told from the inside

- politics made personal

- culture rendered with dignity

- women given agency

- injustice confronted with clarity

- humor used as resistance

- cinema transformed into activism

He believed that Africa’s liberation was incomplete without cultural liberation. He saw cinema as a tool for awakening the conscience of a continent. And he proved, again and again, that African stories belong to Africans—not filtered, not diluted, not colonized by foreign tastes.

Ousmane Sembène’s cinema transcends analysis. It pulses with life. It is cinema as witness, cinema as rebellion, cinema as love for one’s people.

Sembène’s films remain essential not just for cinephiles of African cinema, but for anyone who believes cinema can change the world. His voice endures—firm, uncompromising, compassionate—reminding us that storytelling is an act of freedom, and freedom demands courage.

He once said he wished to be remembered as the man who “awakened African consciousness.”

He succeeded.