Of all the cinematic genres that have captured the public’s imagination, few are as grand in scale, as primal in their conflict, or as paradoxically revered and ridiculed as the sword-and-sandal film. Known to purists by its more academic Italian name, peplum (after the Greek tunic worn by its heroes), this is a genre of muscle-bound titans, of decadent empires and virtuous rebels, of clashing steel and stirring orchestral scores. To the casual observer, it might seem a relic, a curious fad of mid-century cinema populated by bodybuilders in loincloths. But to the cinephile who dares to look beyond the often-wobbly sets and occasionally stilted dubbing, the peplum is a rich, complex, and enduring cinematic tradition. It is a genre that speaks to fundamental human desires for justice, freedom, and physical prowess, a canvas for political allegory, and a playground for visual stylists. This is a journey through the sun-drenched arenas and marble palaces of the sword-and-sandal epic, focusing on its triumphant peaks, the visionary directors who shaped it, and the enduring legacy of its most successful films.

The Foundations: Muscles, Myth, and the Silent Era

Before we can understand the golden age, we must first acknowledge the bedrock. The sword-and-sandal genre did not emerge from a vacuum. Its spiritual ancestors are the historical epiques of the silent era, most notably Giovanni Pastrone’s “Cabiria” (1914). This Italian colossus, with a screenplay by the nationalist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, set the template for everything that would follow. It was a film of staggering ambition, featuring the eruption of Mount Etna, the sacrifice of children to the molten god Moloch, and the introduction of the heroic strongman Maciste. Played by Bartolomeo Pagano, Maciste became Italy’s first cinematic superhero, a character so popular he would be resurrected time and again for decades, his name becoming synonymous with the genre itself. “Cabiria” demonstrated the potent combination of mythological spectacle, historical sweep, and a central, physically imposing hero—a formula that would prove timeless.

The genre lay dormant for a time, overshadowed by the rise of Hollywood and the talkies. But the seeds were sown. It would take the convergence of post-war economic realities, a new star from America, and the entrepreneurial spirit of an Italian producer to make them bloom.

The Golden Age: The Hercules Revolution and the Italian Masters

The modern sword-and-sandal boom can be pinpointed with remarkable precision to a single film: “Le Fatiche di Ercole” (Hercules), released in 1958. The catalyst was American bodybuilder Steve Reeves. With his perfect physique, chiseled jaw, and surprising screen presence, Reeves was not just a man; he was a statue of a Greek god come to life. Director Pietro Francisci understood that Reeves’s appeal was not in Shakespearean monologues but in his physicality. The film, made on a modest budget, became a global phenomenon. It wasn’t the plot—a loose amalgamation of the myths of Hercules and Jason—that captivated audiences; it was the image of Reeves, a symbol of pure, uncomplicated strength in a complex, nuclear-aged world.

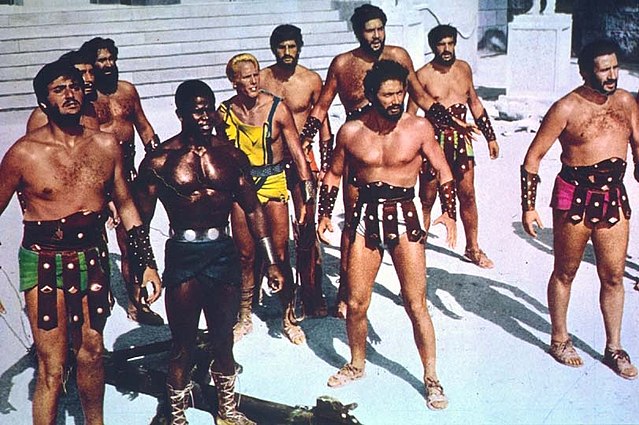

The success of “Hercules” unleashed a tidal wave of peplum that lasted until roughly 1965. Italian studios, particularly Cinecittà, became factories of mythic adventure, churning out dozens of films a year. This was the true golden age, a period of prolific creativity and commercial success built on a set of reliable tropes: the righteous hero, the evil queen or tyrant, the beautiful love interest, the comic-relief sidekick, and the inevitable climactic rebellion. While many of these films were formulaic, the best of them were crafted with artistry, vigor, and a surprising depth.

To understand the golden age is to move beyond Steve Reeves and explore the other key architects of the form.

1. The Star: Steve Reeves and the Physique as Character

Reeves was the archetype. His performances in “Hercules Unchained” (1959) and “The Trojan Horse” (1961) solidified his legend. He possessed an undeniable charisma that transcended language barriers. His Hercules was noble, his Aeneas stoic. He set the standard for the peplum hero: strong, silent, and morally unwavering. But the era was filled with other titans vying for his crown. Gordon Scott, the former Tarzan, brought a rugged earnestness to films like “Goliath and the Vampires” (1961). Mark Forest, with his operatic presence, was a force of nature in films like “The Son of Spartacus” (1962). And then there was Reg Park, whose brawnier, more approachable Hercules in “Hercules and the Captive Women” (1961) and its sequel would famously inspire a young Austrian bodybuilder named Arnold Schwarzenegger.

2. The Visionary Director: Mario Bava

While many peplum directors were competent journeymen, a few were genuine auteurs, and none more so than Mario Bava. A master of light and shadow, Bava used the peplum as a training ground for the gothic horror that would make him immortal. His work in the genre elevates it to high art. In “Hercules in the Haunted World” (1961), starring Reg Park, Bava creates a phantasmagorical landscape that is less classical Greece and more a nightmare from a German Expressionist film. With vibrant Technicolor, ethereal fog, and haunting sets, the film feels like a mythological epic filtered through the sensibilities of Edgar Allan Poe. It is arguably the most visually stunning film of the entire genre.

Bava’s genius is even more evident in “The Giant of Metropolis” (1961), a film that audaciously mashes up the peplum with science fiction. It’s a tale of the lost continent of Atlantis, complete with futuristic technology and a mad scientist, all rendered with Bava’s unparalleled gothic flair. His work demonstrates that the peplum was not a rigid genre but a flexible framework that could accommodate horror, sci-fi, and fantasy, all bound together by the unifying principle of spectacular visual storytelling.

3. The Political Allegorist: Riccardo Freda

A director of immense talent and often fiery temperament, Riccardo Freda brought a layer of intellectual and political subtext to his peplum films. His “The Trojan Horse” (1961), starring Steve Reeves, is a straightforward epic, but his “The Giants of Thessaly” (1960) is more ambitious. However, it is “Spartacus and the Ten Gladiators” (1964) that best showcases his tendency to infuse the genre with contemporary resonance. While not as famous as Kubrick’s film, Freda’s work often hints at critiques of power and the plight of the individual against oppressive systems. He was a craftsman who understood that the struggles of ancient slaves and rebels could mirror the political struggles of the modern world.

4. The Master of Spectacle: Duccio Tessari

Tessari, who would later co-write Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars and become a renowned director of spaghetti westerns and gialli, cut his teeth on peplum. His “The Titans” (1962) is a fascinating oddity, pitting the mythological heroes of Greece against those of the Norse pantheon. But his most significant contribution is “The Son of Spartacus” (1962), a direct attempt to cash in on Kubrick’s hit. Starring the magnetic Steve Reeves-lookalike, Mark Forest, the film is directed with a kinetic energy and a visual polish that sets it apart. Tessari understood pacing and action, skills he would perfect in his later work. His peplum films feel dynamic and modern, less stage-bound and more cinematic.

This golden age was an international affair. The films were shot in Italy, often with multinational casts who spoke their native languages on set, their lines later unified in post-production dubbing. This explains the sometimes-awkward syncing that has become a charming hallmark of the genre. They were co-productions, designed for export, and they found voracious audiences across Europe, the Americas, and beyond, making them some of the most commercially successful European films of their time.

The American Colossus: Hollywood’s Reinvention of the Epic

While Italy was producing a stream of mythological adventures, Hollywood was operating on a different scale entirely. The American sword-and-sandal epic was less about musclemen and more about spiritual and historical grandeur, often with biblical underpinnings. These were prestige pictures, lavished with enormous budgets, major stars, and the full technical might of the studio system.

The undisputed king of this form was William Wyler. His “Ben-Hur” (1959) is not just a successful sword-and-sandal film; it is one of the most successful films of all time, a sweeping triumph that won a record 11 Academy Awards. While it features a phenomenal, famously real chariot race, its power lies in its human drama—the story of betrayal, faith, and redemption between Judah Ben-Hur and Messala. Wyler focused on character and theme, using the spectacle to serve the story, not the other way around. “Ben-Hur” proved that the ancient world epic could be both a colossal commercial blockbuster and a profound work of art.

Simultaneously, a different kind of genius was at work. Stanley Kubrick, taking over from Anthony Mann, directed “Spartacus” (1960). Based on the real-life slave rebellion, the film is a powerful political drama draped in the toga of a historical epic. With a stellar cast led by Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, and Peter Ustinov, Kubrick crafted a film that is fiercely intelligent and emotionally resonant. Its themes of freedom, individuality, and the corrupting nature of power were deeply relevant in Cold War America. The “I am Spartacus!” scene remains one of the most iconic and emotionally charged moments in cinema history. “Spartacus” demonstrated the genre’s potential for serious political commentary.

Other directors contributed to this Hollywood golden age. Anthony Mann’s “The Fall of the Roman Empire” (1964) was a financial failure that bankrupted its studio, but it is now rightly regarded as a masterpiece of intelligent, sober historical filmmaking. Its breathtaking final scene, a visual essay on the transience of power, is a high-water mark for the genre. Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s “Cleopatra” (1963), despite its notorious production troubles and near-fatal cost overruns, is a film of immense spectacle and fascinating, talky drama, anchored by Elizabeth Taylor’s iconic performance.

These American epics shared a common goal with their Italian cousins—to awe and entertain—but they did so with a different toolkit: psychological complexity, A-list actors, and a focus on historical (or biblical) realism over mythological fantasy.

The Modern Resurgence: Revitalizing the Form

After the golden age, the peplum genre faded, parodied into oblivion and supplanted by the spaghetti western and the modern action film. For decades, it seemed like a curious artifact. Then, at the turn of the millennium, a combination of new technology and directorial vision brought the genre roaring back to life.

The film that single-handedly revived the sword-and-sandal for a new generation was Ridley Scott’s “Gladiator” (2000). Scott, a master visual stylist, did not simply make a peplum film; he deconstructed and rebuilt it for a modern audience. He took the revenge plot of a fallen general, Maximus (Russell Crowe), and fused it with the political intrigue of “The Fall of the Roman Empire” and the visceral spectacle of the arena. What set “Gladiator” apart was its gritty, lived-in aesthetic. This was not the clean, brightly colored world of the 1950s; this was a dirty, bloody, and morally complex ancient Rome. The use of CGI allowed for breathtaking recreations of the Colosseum and the scope of the empire, but the film’s heart was its raw, human emotion. Crowe’s performance was grounded and powerful, and Joaquin Phoenix’s Commodus was a pathetic and terrifying villain. “Gladiator” was a colossal critical and commercial success, winning the Academy Award for Best Picture and proving that audiences still craved stories from the ancient world, provided they were told with sophistication and visceral power.

“Gladiator” opened the floodgates. A wave of big-budget historical epics followed, including Wolfgang Petersen’s “Troy” (2004) and Oliver Stone’s “Alexander” (2004). While these films had varying degrees of success, they reaffirmed the genre’s commercial viability.

But the most fascinating and artistically successful evolution of the peplum in the 21st century has been on television. The Starz series “Spartacus: Blood and Sand” (2010), created by Steven S. DeKnight, took the genre in a wildly new direction. Initially dismissed by some as a low-rent “Gladiator” clone, the series quickly revealed itself to be something unique: a hyper-stylized, visceral, and surprisingly sophisticated drama. Drawing heavily from graphic novels and video games in its visual language (slow-motion blood sprays, digital backgrounds), the show delivered brutal, balletic action. But beneath the stylized violence was a compelling narrative about brotherhood, love, loss, and the corrosive nature of power. The tragic, real-life death of its original star, Andy Whitfield, and his replacement by Liam McIntyre, added a layer of profound, meta-textual poignancy to the story of a man fighting against his own mortality. “Spartacus” is a prime example of how the core tenets of the peplum—the rebellion against tyranny, the celebration of physical prowess, the exploration of honor and loyalty—can be repackaged for a modern sensibility without losing their power.

The Auteurs of the Modern Era

The modern resurgence has also been defined by a new generation of directors who have used the genre as a platform for their distinct visions.

1. Ridley Scott: The Grand Visualist

With “Gladiator,” Scott redefined the look and feel of the ancient world. He returned to it with “Kingdom of Heaven” (2005), a film whose Director’s Cut is rightly considered a masterpiece of the historical epic. Scott used the Crusades as a backdrop to explore themes of religious tolerance, leadership, and the search for peace in a violent world. His world-building is unparalleled; his ancient cities feel populated, gritty, and real. Scott proves that the epic can be a vehicle for complex ideas and breathtaking imagery.

2. Zack Snyder: The Stylist of Myth

Snyder’s “300” (2006) is perhaps the most pure, distilled form of the modern peplum. Based on Frank Miller’s graphic novel, it makes no pretense of historical accuracy. Instead, it is a mythic fantasia, a testosterone-fueled tone poem about sacrifice and freedom. Its entirely digital backdrops, hyper-saturated color palette, and extensive use of slow-motion created a look that was instantly iconic and widely imitated. “300” is less a film about the Battle of Thermopylae than it is a film about the idea of the Battle of Thermopylae—the legend, the propaganda. In this, it shares a surprising kinship with the mythological spirit of the Italian peplum, which was always more concerned with archetype than history.

The Enduring Appeal: Why the Peplum Still Matters

The sword-and-sandal film, from “Cabiria” to “Spartacus,” has endured for over a century because it taps into fundamental, timeless narratives.

- The Power Fantasy: At its core, the peplum is about the triumph of the individual against impossible odds. Whether it’s Hercules lifting a boulder or Maximus defeating a champion in the arena, it fulfills a deep-seated human desire to see strength and virtue prevail over corruption and brute force.

- The Political Allegory: The genre is a perfect vessel for political commentary. The struggle of slaves against a decadent empire (“Spartacus”), of a righteous man against a corrupt emperor (“Gladiator”), or of a city-state against a tyrannical king (“300”) can be easily mapped onto contemporary conflicts, from the Cold War to the War on Terror.

- Moral Clarity: In an increasingly complex world, the peplum often offers a refreshing moral simplicity. The hero is strong and good, the villain is wicked and decadent. This clear dichotomy provides a satisfying narrative catharsis that more ambiguous modern stories often deny us.

- Pure Spectacle: Finally, these films are about awe. The sight of a thousand ships sailing for Troy, the roar of the crowd in the Colosseum, the impossible architecture of a mythical city—these are the dreams of cinema made real. They transport us to a world larger and more dramatic than our own.

Conclusion: A Legacy Cast in Bronze

The sword-and-sandal epic is far more than a kitsch footnote in film history. It is a resilient and adaptable genre that has cycled through periods of immense popularity and artistic innovation. From the mythic foundations of “Cabiria” and the muscle-bound revolution of Steve Reeves, through the gothic beauty of Mario Bava and the political heft of Kubrick’s “Spartacus,” to the gritty revival of “Gladiator” and the hyper-stylized fury of the “Spartacus” series, the peplum has consistently found new ways to tell the oldest of stories.

It is a genre that celebrates the human form, wrestles with the nature of power, and provides a canvas for some of cinema’s most visionary directors to paint on a grand scale. To dismiss it is to ignore a vital strand of our cinematic DNA. The sword-and-sandal film, in all its sweaty, glorious, and spectacular forms, remains a testament to the enduring power of myth, the thrill of the spectacle, and the timeless appeal of a hero with a sword in his hand, standing against the darkness. The arena gates are never closed for long; we need only wait for the next champion to enter, ready to once again make the genre feel new.