There’s a moment in Yu Hyun-mok’s “Obaltan” where the protagonist, Cheolho, sits in a taxi, blood dripping from his mouth after having his teeth extracted, and keeps changing his destination—from the morgue to the hospital to the police station—never settling on any direction. The taxi driver calls him an aimless bullet, and Cheolho can only echo his senile mother’s desperate refrain: “Let’s get out of here!” It’s a scene of such devastating existential clarity that it crystallizes everything Yu Hyun-mok brought to Korean cinema—an unflinching gaze at human suffering, an intellectual rigor that refused easy answers, and a visual poetry that transformed despair into art.

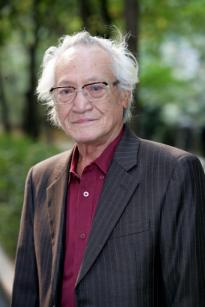

For those of us who’ve spent years excavating the golden age of Korean cinema, Yu Hyun-mok represents something rare and essential: a filmmaker who thought cinematically before thinking dramatically, who believed film should confront society rather than comfort it, and who possessed the courage to make that vision reality even when it cost him everything. Born on July 2, 1925, in Sariwon, in what is now North Korea, Yu directed over 40 films across five decades, earning recognition as one of the three master filmmakers—alongside Kim Ki-young and Shin Sang-ok—who defined Korean cinema’s emergence from colonial occupation into artistic maturity.

The Formation of a Visual Thinker

Yu’s path to cinema was shaped by displacement and education in equal measure. Growing up during the Japanese colonial period, he developed an early fascination with visual arts—a passion that would distinguish his approach to filmmaking throughout his career. Unlike many of his contemporaries who came to film through theater or literature, Yu’s sensibility was fundamentally pictorial. He once stated that he sought to “think cinematically,” and this wasn’t mere rhetoric. His films are constructed through mise-en-scène, framing, lighting, and camera movement rather than through dialogue or plot mechanics.

After studying at Dongduk Korean Language School and graduating from the Department of Korean Literature, Yu entered the film industry during Korea’s immediate post-liberation period. He made his directorial debut with “Crossroads” in 1956, at a time when Korean cinema was still finding its voice after decades of Japanese suppression. The 1950s were years of experimentation for Yu, making films like “Sadness of Heredity” (1956), “Lost Youth” (1957), and “Forever With You” (1958), steadily developing his craft while Korean society tried to rebuild itself from the devastation of the Korean War.

But these early works, competent as they were, gave little indication of the masterpiece that was coming.

“Obaltan”: The Film That Changed Everything

When “Obaltan” (also known as “Aimless Bullet” or “Stray Bullet”) was released in April 1961, it arrived during a brief window of artistic freedom between the ousting of Syngman Rhee’s corrupt government and the military coup that would spawn Park Chung-hee’s dictatorship. This fleeting moment of openness allowed Yu to make a film of devastating honesty—one that would be banned almost immediately for its unremittingly bleak portrayal of post-war South Korean society.

The film follows Cheolho, an underpaid accountant struggling to support his pregnant wife, their daughter, and his extended family in a cramped Seoul dwelling. His younger brother Yeongho is an angry war veteran who feels unrewarded for his service. Their sister Myeongsuk, ashamed but pragmatic, works as a prostitute serving American soldiers. Their youngest brother has dropped out of high school to sell newspapers. Presiding over this microcosm of national trauma is their mother, mentally unhinged and bedridden, who constantly screams “Let’s get out of here!”—a plea that encapsulates the family’s collective desperation while reminding them there is nowhere to go.

Based on Yi Beomseon’s novella, the film is routinely cited as the greatest Korean film ever made, topping numerous critics’ polls over the decades. What makes it extraordinary isn’t just its subject matter but Yu’s formal approach to depicting despair. The film is commonly described as an exemplar of Korean neorealism—critics have compared it to De Sica’s “Bicycle Thieves” and noted its kinship with Italian postwar cinema—but this categorization, while not wrong, is incomplete.

Yu incorporates neorealist sensibilities, certainly, but “Obaltan” is stylistically eclectic in ways that reveal his modernist ambitions. The opening sequence features a replica of Rodin’s “The Thinker” behind prison bars, with eerie light cutting through darkness—a clear gesture toward expressionism. Throughout the film, Yu deploys German expressionist techniques, Soviet montage theory, film noir shadows, and even melodramatic conventions borrowed from Hollywood. There’s a scene recreating the shared cigarette lighting from “Love is a Many-Splendoured Thing,” but in Yu’s hands, this gesture becomes charged with erotic desperation—a brief grasping at pleasure within a realm of unrelenting misery.

The film’s climax during a bank robbery features marching citizens carrying Christian placards, blending noir aesthetics with religious imagery in a way that’s both jarring and profound. And those final images of Seoul border on abstraction, the city dissolving into shapes and shadows that suggest psychological disintegration as much as physical geography.

This stylistic hybridity—which some might mistake for inconsistency—is actually evidence of Yu’s sophisticated approach to genre. Korean cinema’s tendency toward genre mixing isn’t a recent phenomenon; Yu was practicing it at the highest level in 1961. He understood that capturing the full complexity of postwar trauma required drawing from multiple cinematic traditions, that no single style could contain the contradictions of a society torn between American occupation, Confucian tradition, capitalist modernization, and the open wound of national division.

The film’s production was troubled. Made on a shoestring budget with a stop-start production schedule, “Obaltan” has occasional visual inconsistencies that betray its difficult birth. But not all the stylistic variations stem from financial constraints. Yu was deliberately breaking barriers—artistic, social, and political—and the film’s formal restlessness mirrors the aimlessness of its characters.

The government banned “Obaltan” almost immediately because of its downbeat depiction of South Korean life. That ban might have been permanent if not for an American consultant to the Korean National Film Production Center who saw the film and persuaded authorities to release it in Seoul so it could qualify for the San Francisco International Film Festival. In November 1963, Yu attended the film’s premiere in San Francisco, where Variety called it remarkable and praised his brilliantly detailed camera and the film’s probing sympathy and rich characterizations.

That international recognition proved crucial. “Obaltan” demonstrated that Korean cinema could compete artistically on the world stage, that films addressing Korea’s specific traumas could resonate universally. The restoration completed by the Korean Film Archive in 2015 has allowed new generations to discover this masterwork, ensuring its place in world cinema history.

Beyond the Aimless Bullet

Yu’s career didn’t begin or end with “Obaltan,” though that film will forever define his legacy. In the same year, 1961, he also directed “Im Kkeok-jeong,” a historical epic based on Hong Myung-hee’s novel about the legendary Joseon-era outlaw—Korea’s equivalent of Robin Hood. The film went missing at some point, its original print lost to time or negligence. But in 2022, the Korean Film Archive discovered a 35mm reel at the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation at the Library of Congress. After a year-long restoration process involving physical repair and digital scanning in the United States, followed by color correction and sound cleanup in Korea, “Im Kkeok-jeong” was reborn in 4K.

This recovery is remarkable not just for restoring a lost work but for revealing Yu’s range. While “Obaltan” excavates contemporary suffering, “Im Kkeok-jeong” looks backward to find resonance in historical rebellion. It’s a rare epic in Yu’s filmography, proving he could work in multiple registers while maintaining his distinctive visual intelligence.

“Daughters of Pharmacist Kim” (1963), adapted from Park Kyong-ni’s novel, explores sibling rivalry and the troubled marriages of four sisters. The film examines how traditional patriarchal structures constrain women’s lives while modern pressures create new forms of suffering. Yu’s interest in female experience—unusual for male directors of his era—produced work of genuine empathy and insight. The film was successful enough that MBC adapted it as a television series in 2005, testament to the story’s enduring relevance.

Throughout the 1960s, Yu continued making films that challenged audiences and authorities alike. “To Give Freely” (1962) earned him his first Blue Dragon Award for Best Director. “The Extra Mortals” (1964) further developed his interest in social outsiders. “Martyr” (1965), which explored Christian faith directly, became the first Korean film exported to the United States and earned another Blue Dragon for Best Director. That same year, however, Yu was arrested on charges of violating the Anti-Communist Law—charges from which he was later pronounced innocent, but which demonstrated the dangers facing filmmakers who insisted on artistic independence.

“Descendants of Cain” (1968) tackled issues of class and morality. “Bun-Rye’s Story” (1971) earned Yu his third Blue Dragon for Best Director. “Flame” (1975) brought him his fourth Blue Dragon and the Grand Bell Award for Best Picture, cementing his reputation as Korean cinema’s most awarded director.

“Rainy Days” (1979) marked another late-career triumph, demonstrating that Yu’s powers hadn’t diminished with age. His final feature, “Mom, the Star, and the Sea Anemone” (1996), arrived after a long hiatus, a meditative work that showed an older filmmaker still grappling with fundamental questions about human existence and family bonds.

The Intellectual Approach and Political Persecution

Yu’s dedication to film’s intellectual possibilities set him apart from commercially-oriented producers and made him a target for Korea’s military government during the 1960s and 1970s. While directors like Shin Sang-ok built production empires and navigated political pressures through sheer prolific output, Yu took a different path. He was slower, more deliberate, insistent on artistic control even when it meant professional hardship.

This commitment cost him. His films frequently clashed with box-office expectations. Producers wanted melodramas and escapist entertainment; Yu wanted to confront society with its own image. The Park Chung-hee regime, which ruled South Korea with increasing authoritarianism from 1961 to 1979, viewed cinema primarily as a propaganda tool or, at best, harmless entertainment. Filmmakers who insisted on social criticism faced censorship, financial pressure, and worse.

Yu’s Christian faith informed his worldview without overwhelming his artistic vision. Unlike some Christian filmmakers who reduce complexity to spiritual platitudes, Yu understood that faith doesn’t erase suffering—it provides a framework for enduring it. “Martyr” and “Son of Man” (1980) explore religious themes directly, but even in ostensibly secular films like “Obaltan,” brief Christian imagery appears—not as answers but as one more element in the chaotic landscape of postwar Korean life.

Building Film Culture Beyond Directing

Yu understood that Korean cinema needed infrastructure—not just studios and theaters, but intellectual frameworks and cultural institutions. In 1970, he founded the Korea Amateur Filmmakers Association (KAMA), creating space for experimental work outside commercial constraints. He initiated projects through groups like Cinepoem and the Korean Small-Gauge Film Club, encouraging filmmakers to explore cinema’s artistic possibilities without worrying about commercial viability.

Through Yu Production, he produced cultural and animated films, including Kim Cheong-gi’s “Robot Taekwon V” (1976)—a project that seems surprising given Yu’s reputation for austere realism, but which demonstrates his commitment to developing Korean animation as an industry. He founded the East-West Film Study Society to promote the cinematheque movement, arguing that Korean filmmakers and audiences needed access to world cinema’s full range.

Perhaps most importantly, Yu taught. From 1963 onward, he taught at Dongguk University, eventually becoming a full professor in 1976 and dean of the Department of Arts in 1989. His students carried his influence forward, spreading his belief that cinema should think, should challenge, should refuse to look away from difficult truths. Korean film critic Byun In-shik once declared that “Yu Hyun-mok is cinema”—not as hyperbole but as recognition that Yu embodied what Korean cinema could aspire to be.

In 1977, Yu took over as director of the Korean Film Archive, working to preserve Korean cinema’s history at a time when neglect and deterioration threatened to erase entire eras. This institutional work, less glamorous than directing, proved crucial for ensuring that future generations could study and learn from Korean cinema’s golden age.

The Formal Signature

What distinguishes a Yu Hyun-mok film? It’s tempting to focus on content—the social criticism, the unflinching portrayal of poverty and trauma—but Yu’s real signature lies in his visual approach. He composes frames with a painter’s eye, using light and shadow to create psychological landscapes. His camera movements are purposeful, never merely functional. He understands that where you place the camera and how you light a scene communicate as much as dialogue.

Watch how he uses doorways and windows as frames within frames, creating layers of enclosure that mirror his characters’ trapped circumstances. Notice his willingness to hold shots longer than conventional editing would suggest, forcing audiences to sit with discomfort rather than cutting away. Observe his use of depth of field to suggest social hierarchies—foreground figures dominating the frame while others recede into background blur.

Yu absorbed influences from Italian neorealism, German expressionism, Soviet montage, and American film noir, but he synthesized these into something distinctively Korean. His films engage with specifically Korean traumas—the colonial experience, the Korean War, national division, rapid modernization under authoritarian rule—while employing a visual language that international audiences could understand. This combination of local specificity and formal sophistication explains why his work has aged so well.

Recognition and Legacy

Yu received numerous honors during his career. He won the Blue Dragon Award for Best Director four times—for “To Give Freely,” “Martyr,” “Bun-Rye’s Story,” and “Flame.” In 1988, he received an Order of Cultural Merit from the Korean government. In 1989, he was elected chairman of the Film Art Society of Korea. In 1995, the Grand Bell Awards gave him an Honorary Director Award.

The 1999 Busan International Film Festival held a major retrospective of his work, introducing his films to a new generation of cinephiles. San Sebastián International Film Festival has featured his work in explorations of Korean cinema’s golden age. In 2017, the Nantes Three Continents Film Festival, Paris Korean Film Festival, and other venues showcased his films internationally, ensuring his work reaches beyond Korean borders.

In 2025, the Korean Film Archive organized “Yu Hyun-mok Centennial: Era, Genre, Practice,” a comprehensive retrospective featuring 18 works: 16 narrative features, the animated film “Robot Taekwon V” that he produced, and a film essay reinterpreting his cinematic world. The program highlighted newly restored works, including the 4K restoration of “Im Kkeok-jeong” and “The Martyr,” alongside 35mm screenings of “Forever With You” and “Bun-Rye’s Story.”

Yu Hyun-mok passed away on June 28, 2009, at age 83 from a stroke. His death marked the end of an era, the passing of one of the last direct connections to Korean cinema’s golden age. But his films remain vibrantly alive, speaking to contemporary audiences with undiminished power.

Reflections on a Cinema Poet

I keep returning to that taxi ride at the end of “Obaltan.” Cheolho, bloodied and aimless, unable to decide where to go because every destination offers only more suffering. The taxi continues driving, and we never learn Cheolho’s fate. Yu refuses to offer closure because life offers none. The aimless bullet keeps traveling, directionless but unstoppable, until something—anything—brings it to rest.

This refusal of easy answers defines Yu’s cinema. He understood that art’s job isn’t to solve problems but to make them visible, to force society to confront what it would rather ignore. His films don’t offer hope because hope, in the worlds he depicts, would be obscene. But neither do they counsel despair. Instead, they insist on witness—on seeing clearly, on acknowledging suffering without turning away.

What strikes me most about Yu Hyun-mok’s career is his consistency. He never sold out, never compromised his vision for commercial success or political favor. This cost him financially and professionally, but it ensured his artistic integrity. While other directors of his generation made occasional masterpieces between commercial projects, Yu maintained a remarkably high standard across his filmography. Not every film reaches the heights of “Obaltan,” but none feel like hack work, none betray the intellectual and ethical commitments that defined his approach.

His influence on subsequent Korean filmmakers is profound, though sometimes hard to trace directly. You see it in Im Kwon-taek’s commitment to Korean stories told with formal sophistication. You see it in Lee Chang-dong’s intellectual approach to social criticism. You see it in Hong Sang-soo’s willingness to make small, difficult films that prioritize artistic vision over commercial calculation. You see it in Park Chan-wook‘s formal inventiveness and Bong Joon-ho‘s genre hybridity.

These directors may not cite Yu Hyun-mok as explicitly as they might cite foreign influences, but his example—that Korean cinema could be intellectually serious, formally ambitious, and uncompromisingly honest—created the possibility for their careers to exist.

The Essential Question

The title “Obaltan” contains a linguistic richness that English translations can’t quite capture. “Obaltan” can mean “aimless bullet,” “stray bullet,” or “misfired shot”—each translation emphasizing different aspects of the metaphor. An aimless bullet travels without purpose or destination. A stray bullet hits unintended targets, causing random damage. A misfired shot fails to achieve its intended purpose from the moment it’s fired.

All three meanings apply to Yu’s characters and, by extension, to post-war Korean society. People trying to live with purpose but finding themselves directionless. People damaged by forces beyond their control or understanding. People whose efforts fail before they begin, not through any fault of their own but because the entire system is broken.

Yet Yu insists we see these aimless bullets as human beings deserving of dignity and sympathy. Cheolho isn’t a failure—the society that offers him no place has failed. Myeongsuk isn’t immoral for surviving however she can—the morality that judges her while offering no alternative has failed. Yeongho isn’t lazy or ungrateful—the nation that demanded his service then abandoned him has failed.

This insistence on locating failure in systems rather than individuals, on maintaining sympathy even for deeply flawed characters, marks Yu as a profoundly humanistic filmmaker. His realism isn’t about documenting poverty for its own sake but about insisting that the poor, the traumatized, the broken deserve our attention and our care.

A Cinema That Endures

Korean cinema’s current international prominence—from festival success to Oscar wins to global streaming audiences—rests on foundations laid by filmmakers like Yu Hyun-mok. He proved that Korean stories told with Korean voices could achieve artistic excellence by any standard. He demonstrated that formal sophistication and social engagement could coexist, that you didn’t have to choose between art and advocacy.

Most importantly, he showed that refusing to compromise, insisting on artistic integrity even at great personal cost, could produce work that lasts. “Obaltan” is as powerful today as it was in 1961 because it doesn’t rely on topical references or dated aesthetics. Its formal intelligence and ethical seriousness transcend their immediate context to address universal questions about human suffering and dignity.

When I watch Yu Hyun-mok’s films, I’m reminded why I fell in love with Korean cinema in the first place. Not because of spectacular action sequences or melodramatic twists, but because of this tradition of filmmakers who believe cinema matters, who insist that how you point the camera and where you cut carries moral weight, who refuse to turn away from difficult truths.

Yu Hyun-mok is cinema, as Byun In-shik said. Not all of cinema—there’s room for entertainment, for escapism, for pure formal play—but cinema at its most essential. Cinema as witness, as conscience, as poetry emerging from despair. The aimless bullets of his films keep traveling through time, finding new targets, striking new viewers with the force of their terrible beauty.

For cinephiles exploring Korean cinema’s golden age, Yu Hyun-mok isn’t optional viewing—he’s the foundation everything else is built on. To understand Korean cinema is to understand what Yu Hyun-mok achieved and why it cost so much to achieve it. His films remain essential not as historical artifacts but as living works that continue asking questions we haven’t yet learned how to answer.

The taxi is still driving. Cheolho is still bleeding. The aimless bullet is still traveling. And we are still watching, trying to understand where we’re going, trying to figure out how to get out of here.