Among the pantheon of world cinema’s great achievements, few trilogies have approached ancient Greek tragedy with the reverence, authenticity, and cinematic mastery displayed in Michael Cacoyannis’ extraordinary three-film cycle adapted from the works of Euripides. Spanning fifteen years from 1962 to 1977, the Trojan Trilogy—comprising Electra, The Trojan Women, and Iphigenia—stands as a monumental artistic accomplishment that bridges the ancient and modern worlds, bringing the timeless power of classical Greek drama to audiences through the medium of film.

Michael Cacoyannis, born in Limassol, Cyprus, on June 11, 1922, emerged as one of the most significant figures in Greek cinema during the 20th century. While he achieved international fame with his 1964 masterpiece Zorba the Greek, which earned seven Academy Award nominations and brought Greek culture to global audiences, it is perhaps his Euripidean trilogy that represents his most profound artistic legacy. These three films demonstrate not merely adaptation but a deep, personal engagement with the source material—a reincarnation of ancient tragedy filtered through the sensibilities of a master filmmaker who understood both the theatrical traditions of his heritage and the unique possibilities of cinema.

The Genesis of a Trilogy: Electra (1962)

The trilogy began with Electra in 1962, a bold and uncompromising adaptation of Euripides’ tragedy that would establish the aesthetic and thematic foundations for the films to follow. Shot on location in the sun-drenched landscapes of Mycenae and Argos, the film tells the story of Agamemnon’s daughter, consumed by hatred for her mother Clytemnestra and stepfather Aegisthus, who murdered her father upon his return from the Trojan War. Living in exile and forced into a degrading marriage to a peasant, Electra’s burning desire for vengeance finally finds fulfillment when her brother Orestes returns, and together they execute their terrible revenge.

What distinguishes Cacoyannis’ Electra from other adaptations of Greek tragedy is its stark cinematic language and visceral authenticity. The director made the crucial decision to film entirely in Greek with Greek actors, lending the production an organic quality that transcends mere historical recreation. The film’s visual aesthetic, captured by cinematographer Walter Lassally in rich black and white, transforms the ancient ruins of Mycenae into a living, breathing world where myth and reality converge. The harsh Mediterranean sun creates deep shadows and brilliant highlights that mirror the moral absolutes of the tragedy, while the barren landscapes evoke both the material poverty of Electra’s existence and the spiritual desolation of her quest for revenge.

At the center of the film stands Irene Papas in a career-defining performance as Electra. Papas, who would become Cacoyannis’ muse throughout the trilogy, brings to the role an intensity and physicality that feels both ancient and timeless. Her Electra is not a delicate princess but a woman hardened by suffering, her body language conveying years of suppressed rage and grief. The performance relies heavily on gesture and expression rather than dialogue, approaching the visual eloquence of silent cinema. When she finally unleashes her fury in the film’s climactic scenes, the emotional power is overwhelming.

The musical score by Mikis Theodorakis deserves special mention as an integral component of the film’s success. Theodorakis, who would collaborate with Cacoyannis on all three films in the trilogy as well as on Zorba the Greek, created a soundscape that is at once primitive and sophisticated, using traditional Greek instruments and modal melodies to evoke the ancient world while maintaining a modernist edge. The music functions almost as a Greek chorus, commenting on the action and heightening the emotional stakes at crucial moments.

Electra premiered at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the award for Best Cinematic Transposition, recognizing Cacoyannis’ achievement in translating theatrical tragedy into cinematic art. The film also received Greece’s submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and swept the Thessaloniki Film Festival, winning awards for Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actress. Beyond its festival success, Electra introduced international audiences to a new approach to filming Greek tragedy—one that emphasized visual storytelling over theatrical convention, location shooting over studio sets, and emotional authenticity over archaeological accuracy.

A Decade of Transformation: From Electra to The Trojan Women

The nine years between Electra and the second installment of the trilogy were eventful ones for both Cacoyannis and Greece. The director achieved his greatest commercial success with Zorba the Greek in 1964, a film that paradoxically both elevated his international profile and somewhat overshadowed his more serious artistic work. During this period, he also staged theatrical productions of Greek tragedy in Italy, New York, and Paris, including a 1963 production of The Trojan Women that featured Rod Steiger, Claire Bloom, and Mildred Dunnock. These stage productions served as crucial preparation for what would become the second film in his trilogy.

More significantly, Greece underwent a traumatic political transformation with the military coup of 1967, which established a dictatorial junta that would rule until 1974. Cacoyannis, who had become increasingly politically engaged, went into exile. This context of political oppression and resistance would deeply inform his approach to The Trojan Women, transforming Euripides’ meditation on the futility of war into a powerful protest against contemporary violence and authoritarianism.

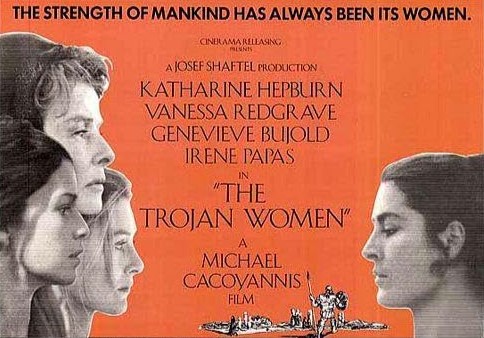

The Trojan Women (1971): An International Production

Released in 1971, The Trojan Women represented both an expansion and a departure from the approach Cacoyannis had established with Electra. The film chronicles the final days of Troy after its fall to the Greeks, focusing on the surviving Trojan women as they await their fates—to be distributed among the Greek victors as slaves and concubines. Queen Hecuba mourns the destruction of her city and the loss of her family, while Andromache, widow of the great warrior Hector, faces the horrifying prospect of seeing her young son Astyanax murdered by the Greeks, who fear he might grow up to avenge his father.

Unlike the intimate, all-Greek production of Electra, The Trojan Women was an international co-production involving Greece, the United States, and Great Britain, featuring a stellar cast of international stars: Katharine Hepburn as Hecuba, Vanessa Redgrave as Andromache, Geneviève Bujold as Cassandra, and Irene Papas as Helen of Troy. The film was shot in Spain rather than Greece, filmed in English rather than Greek, and designed for a global audience. These changes, necessitated by the need for international financing and driven by Cacoyannis’ ambition to reach the widest possible audience with his anti-war message, have made The Trojan Women the most controversial entry in the trilogy.

Critics and scholars have long debated whether the internationalization of the production enhanced or diminished the film’s impact. Some argue that compared to Electra, The Trojan Women lacks the raw authenticity and naturalness that came from filming in Greece with Greek actors speaking their native language. The Spanish location, while visually striking with its abandoned hilltop castle serving as the ruins of Troy, lacks the specific resonance of actual Greek archaeological sites. The international cast, despite their considerable talents, brings varying levels of familiarity with the material and different acting traditions to their roles.

Yet these criticisms, while not without merit, perhaps miss the larger achievement of the film. Cacoyannis deliberately chose to emphasize the universal dimensions of Euripides’ tragedy, making it speak to contemporary audiences about the Vietnam War, the Greek junta, and the endemic violence of the 1960s and 1970s. As the director himself stated in a 1971 interview, he felt the play’s message about the folly of war was as important in his time as when it was written. By creating a more accessible, international production, he ensured that this message would reach far beyond the art house cinema circuit.

The film’s most powerful moments come from its unflinching depiction of the psychological and physical brutality inflicted on the conquered. The scene in which Astyanax is torn from his mother’s arms to be thrown from the walls of Troy remains devastating in its emotional impact. Katharine Hepburn’s Hecuba, initially criticized by some for being too theatrical, ultimately embodies the dignified suffering of a queen who has lost everything but maintains her humanity. The film sacrifices some of the ambiguity present in Euripides’ original text in favor of emotional clarity and political urgency, a choice that reflects Cacoyannis’ belief in the immediate relevance of the material to contemporary crises.

Visually, The Trojan Women maintains Cacoyannis’ commitment to outdoor shooting and natural light, though the color cinematography by Alfio Contini differs markedly from Walter Lassally’s stark black and white work on Electra. The film employs a more theatrical blocking style, with characters often positioned in tableaux that recall classical sculpture and ancient vase paintings. This stylization, combined with Theodorakis’ haunting score, creates a deliberate sense of ritual and ceremony that underscores the tragic inevitability of the events depicted.

The Culmination: Iphigenia (1977)

Six years after The Trojan Women, Cacoyannis completed his trilogy with Iphigenia, widely regarded as the finest achievement of the three films and perhaps the director’s masterpiece. Based on Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis, the film serves as a prequel to the other two entries, depicting events that occurred before the Trojan War even began. The Greek army, assembled at Aulis and ready to sail to Troy, finds itself becalmed by a lack of wind. The seer Calchas declares that the goddess Artemis, angered by the killing of one of her sacred deer, demands the sacrifice of King Agamemnon’s daughter Iphigenia in order to allow the fleet to sail.

For Iphigenia, Cacoyannis returned to the approach that had served him so well with Electra: an all-Greek cast, shooting on location in Greece (specifically at Aulis itself), and dialogue in Greek. The result is a film that combines the authentic power of the first entry in the trilogy with the cinematic sophistication and political consciousness developed through his work on The Trojan Women. The film represents a perfect synthesis of Cacoyannis’ evolving approach to adapting Greek tragedy for cinema.

The screenplay, entirely written by Cacoyannis, demonstrates a masterful understanding of how to translate ancient drama into cinematic narrative. He made significant structural changes to Euripides’ original, placing the story in strict chronological order and adding characters—notably Odysseus, Calchas, and the army itself—who do not appear in the ancient play but whose presence clarifies the political dynamics at work. These additions transform the tragedy from a family drama into a broader examination of how political and military power corrupts and destroys, how religious authority can be manipulated for political ends, and how individuals become trapped by forces beyond their control.

The film’s approach to its mythological subject matter is notably realistic, almost documentary-like in its attention to physical detail. The Greek soldiers at Aulis are depicted not as heroic warriors but as grimy, restless men waiting interminably for action, fighting among themselves for food and entertainment. This grounded realism makes the fantastic elements of the story—the divine intervention, the prophecy, the sacrifice—more rather than less powerful, because they emerge from a world that feels tangibly real. Cacoyannis deliberately leaves ambiguous whether the gods truly demand Iphigenia’s sacrifice or whether Calchas and Odysseus are manipulating religious belief for political purposes, a question that resonates with modern secular audiences while remaining true to the source material’s exploration of divine will versus human agency.

The performances in Iphigenia are uniformly excellent, with Kostas Kazakos bringing genuine anguish and complexity to Agamemnon, a man trapped between paternal love and political necessity. Irene Papas, now playing Clytemnestra (the mother of the Electra she had portrayed fifteen years earlier), delivers what may be her finest work in the trilogy, channeling a mother’s fury and despair with devastating intensity. But the revelation of the film is young Tatiana Papamoschou, only thirteen years old during filming, whose portrayal of Iphigenia moves from innocent joy to confusion to terror to noble acceptance with astonishing maturity and emotional depth.

The cinematography by Giorgos Arvanitis captures the rugged beauty of the Greek landscape, using natural light to create images of extraordinary power. The film’s visual language combines the stark contrasts of Electra with a more fluid camera style that emphasizes the characters’ emotional states. The sequence in which Iphigenia attempts to escape, running through the forests like a hunted animal in parallel to the sacred deer killed at the film’s opening, demonstrates Cacoyannis’ complete mastery of cinematic storytelling, conveying complex ideas and emotions through pure visual means.

The film’s conclusion remains one of the most devastating in all of cinema. Cacoyannis makes the crucial decision to render Iphigenia’s fate ambiguous. In Euripides’ original play, a messenger reports that the goddess Artemis miraculously substituted a deer for Iphigenia at the moment of sacrifice, saving the girl’s life. Cacoyannis omits this consoling resolution, instead showing us only clouds and mist, followed by Agamemnon’s shocked, grief-stricken face. The ambiguity forces viewers to confront the horror of child sacrifice without the comfort of divine intervention, making the tragedy’s critique of war and political ambition all the more powerful.

Iphigenia received widespread critical acclaim and numerous awards, including nominations for the Palme d’Or at Cannes and for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. It won Best Film at the Thessaloniki Film Festival, where Papamoschou also received Best Actress honors. The film was recognized not only as a superb adaptation of Greek tragedy but as a major cinematic achievement in its own right, cementing Cacoyannis’ reputation as one of the great auteurs of world cinema.

The Trilogy as a Unified Vision

Viewed together, the three films of Cacoyannis’ Trojan Trilogy form a remarkably coherent artistic statement despite their fifteen-year span and varying production circumstances. The chronological order of the stories—Iphigenia as prequel, The Trojan Women depicting the war’s end, and Electra showing the aftermath—creates a sweeping narrative arc that encompasses the entire Trojan War cycle and its consequences. Thematically, the films explore recurring concerns: the futility and horror of war, the abuse of political and religious authority, the suffering of women in patriarchal society, and the inescapable chains of fate and vengeance.

The presence of Irene Papas in all three films, playing different roles, provides a remarkable through-line that emphasizes the cyclical nature of tragedy in the House of Atreus. She is the vengeful daughter in Electra, the war prize Helen in The Trojan Women, and the bereaved mother Clytemnestra in Iphigenia. This progression reflects the various faces of female suffering and agency in Greek tragedy, while Papas’ commanding presence ensures that these women are never merely victims but complex individuals struggling against overwhelming forces.

Cacoyannis’ approach to filming Greek tragedy influenced numerous filmmakers who would tackle similar material. His emphasis on location shooting, natural light, and minimal dialogue in favor of visual storytelling demonstrated that ancient drama could be adapted for cinema without resorting to stagey theatrical conventions or Hollywood spectacle. Directors like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Lars von Trier would later explore Greek tragedy on film, but none would create a body of work as sustained and coherent as Cacoyannis’ trilogy.

The Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

More than four decades after the completion of the trilogy, these films remain startlingly relevant. Their exploration of war’s devastating impact on civilians, the manipulation of religious sentiment for political ends, the sacrifice of the innocent for abstract causes, and the cycles of violence that perpetuate themselves across generations speak directly to contemporary global conflicts. The trilogy’s portrayal of women as both victims of patriarchal violence and as agents who resist, endure, and occasionally exact their own terrible vengeance, resonates with ongoing discussions of gender, power, and justice.

The films also serve as an important bridge between classical tradition and modern cinema, demonstrating that ancient texts need not be fossilized museum pieces but living works that can speak powerfully to contemporary audiences when adapted with intelligence, respect, and artistic vision. Cacoyannis showed that faithfulness to the spirit of the original need not mean slavish adherence to every detail, and that thoughtful adaptation can illuminate rather than obscure the essential truths of ancient tragedy.

From a technical standpoint, the trilogy showcases the evolution of film language over a crucial fifteen-year period in cinema history, from the late era of black-and-white cinematography through the maturation of color film technology. The aesthetic differences between the three films reflect broader changes in international cinema during this period, yet Cacoyannis maintained his distinctive authorial voice throughout, never succumbing to passing trends or commercial pressures to dilute his vision.

Conclusion: A Monument of World Cinema

Michael Cacoyannis’ Trojan Trilogy stands as one of the supreme achievements of art cinema, a body of work that successfully translates the power and profundity of ancient Greek tragedy into cinematic form. The three films—Electra, The Trojan Women, and Iphigenia—represent different approaches to the challenge of adaptation, from the intimate authenticity of Electra to the international scope of The Trojan Women to the mature synthesis achieved in Iphigenia. Together, they form a coherent artistic statement that honors the classical tradition while speaking urgently to modern concerns.

The trilogy’s achievement is all the more remarkable for having been realized over such an extended period, during which Cacoyannis navigated commercial success, political exile, and changing production circumstances without losing sight of his artistic vision. His collaboration with actors like Irene Papas, cinematographers like Walter Lassally and Giorgos Arvanitis, and composer Mikis Theodorakis produced works of rare beauty and power that continue to move and provoke audiences decades after their creation.

For students of cinema, the trilogy offers invaluable lessons in adaptation, visual storytelling, and the possibilities of location shooting. For lovers of Greek tragedy, it provides the most successful cinematic realization of Euripides’ vision. For general audiences, it offers an accessible entry point into the world of ancient drama, demonstrating that these two-thousand-year-old stories still possess the power to move, shock, and illuminate. Michael Cacoyannis’ Trojan Trilogy is not merely a great achievement of Greek cinema but a treasure of world cinema, worthy of standing alongside the greatest works of the medium.

As we continue to grapple with war, violence, injustice, and the eternal questions of fate and free will, the trilogy remains as relevant as ever. Cacoyannis understood that Greek tragedy endures not because it offers easy answers or comforting resolutions, but because it forces us to confront the most difficult aspects of human existence with unflinching honesty. In bringing these ancient works to life on film, he created something truly timeless—a cinematic monument that honors the past while speaking directly to the present, ensuring that the voices of Euripides and the tragic women of Troy, Mycenae, and Aulis continue to be heard across the centuries.