Introduction — From Ignorance to Revelation

For years I considered myself a curious, open-minded cinephile. I devoured films from Hollywood to the furthest corners of world cinema, from Italian neorealism to Japanese post-war masters, from New Hollywood rebels to the slow cinema of the Far East. And yet, for reasons I can no longer fully justify, Romanian cinema remained a blind spot. It lingered on the periphery of my cinematic consciousness — acknowledged in festival headlines, respected in theory, but rarely explored with genuine attention.

That distance collapsed the moment I encountered the films of Cristian Mungiu.

What I expected to be austere, socially rigid exercises in realism turned out to be something far more affecting: films of moral tension, emotional precision, and human vulnerability, stripped of ornament yet devastatingly alive. Mungiu did not merely introduce me to Romanian cinema; he dismantled my assumptions about it. Through his work, I discovered a cinema of conscience — one that observes rather than judges, and confronts rather than consoles.

Cristian Mungiu: Formation of a Filmmaker

Cristian Mungiu was born in 1968 in Iași, a culturally rich city in northeastern Romania. His early academic path did not immediately point toward cinema; he studied English literature and worked as a teacher and journalist. This background matters. Mungiu’s films carry the imprint of someone deeply attuned to language, nuance, and social observation — qualities that would later become central to his cinematic voice.

Eventually, Mungiu enrolled at the National University of Theatre and Film in Bucharest, graduating in the late 1990s. His early short films already suggested an interest in realism, ethical tension, and understated drama. But unlike many debut filmmakers, Mungiu never rushed into stylistic excess. His career would unfold slowly, deliberately, with each feature film feeling less like a product and more like a carefully weighed moral inquiry.

A Cinema of Stillness and Moral Weight: Mungiu’s Style

Observational Realism and the Tyranny of Time

One of the defining characteristics of Mungiu’s cinema is his relationship with time. He favors long, uninterrupted takes that resist the nervous cutting patterns of contemporary cinema. These extended shots are not aesthetic indulgences; they are ethical tools. By refusing to cut away, Mungiu forces the viewer to remain inside uncomfortable situations, mirroring the characters’ own inability to escape their circumstances.

Time in Mungiu’s films is not compressed or dramatized — it is endured.

This endurance creates an almost documentary intimacy. Scenes unfold with the weight of real life: pauses linger, silences accumulate meaning, and moments that might be glossed over in conventional cinema become emotionally decisive.

Minimalism Without Coldness

Visually, Mungiu’s films are restrained. Camera movement is sparse, compositions are functional, and lighting is naturalistic. Yet this minimalism never feels sterile. On the contrary, it heightens emotional engagement by stripping away distraction. The absence of non-diegetic music further reinforces this approach. When sound exists, it belongs to the world of the film — footsteps, murmurs, traffic, the hum of everyday life.

This aesthetic humility allows performance to take center stage. Actors in Mungiu’s films do not perform for the camera; they exist within it. Faces become landscapes of hesitation, fear, resignation, and suppressed desire.

Moral Ambiguity as Narrative Engine

Perhaps the most defining feature of Mungiu’s cinema is its moral ambiguity. His films are not interested in heroes or villains. Instead, they explore how ordinary people navigate compromised systems — political, religious, social, and familial.

Mungiu does not offer moral conclusions. He presents situations in all their complexity and leaves judgment suspended. This refusal to moralize is what gives his work such lasting power. The questions linger long after the film ends.

Occident (2002): A Modest Beginning with Hidden Depths

Mungiu’s debut feature, Occident, arrived quietly, without the seismic impact of his later films. Structurally playful and tonally lighter, it explores interconnected stories of Romanians contemplating life in the West. On the surface, the film carries a gentle irony, even humor, but beneath it lies an early exploration of disillusionment, aspiration, and identity.

While Occident lacks the formal severity of Mungiu’s mature work, it already reveals his fascination with people caught between choices, between worlds, and between ideals and reality. In hindsight, it feels like a filmmaker testing his voice before committing fully to the stark realism that would later define him.

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days: Cinema as Moral Reckoning

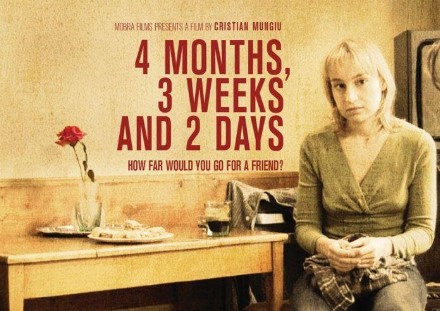

There are films that define careers, and then there are films that redefine national cinemas. 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days does both.

Set during the final years of Romania’s communist regime, the film follows two young women navigating the terrifying logistics of an illegal abortion. What makes the film extraordinary is not its subject matter alone, but how relentlessly Mungiu refuses melodrama. The horror emerges not through spectacle, but through procedure, silence, and moral erosion.

The camera observes rather than dramatizes. A hotel room becomes a site of quiet terror. A dinner table becomes a moral battlefield. The film’s most devastating moments occur not in acts of violence, but in acts of resignation.

Watching 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days for the first time was a turning point for me as a viewer. It was not simply a powerful film — it was an ethical experience. I was no longer watching Romanian cinema from a distance; I was inside it, implicated, unsettled, and transformed.

După dealuri (Beyond the Hills): Faith, Control, and Emotional Devotion

With După dealuri, Mungiu ventured into the volatile territory of faith and institutional power. Inspired by real events, the film explores the reunion of two young women, one of whom has embraced life in an isolated monastery.

What unfolds is not an attack on religion, nor a defense of it, but a tragic examination of belief systems colliding with human fragility. Mungiu’s direction is patient and restrained, allowing ideology to reveal itself through routine, ritual, and repetition.

The monastery is neither demonized nor romanticized. It is presented as a closed moral universe — one that offers meaning, but also demands submission. The tragedy of the film emerges from sincere intentions that gradually spiral into irreversible consequences.

Bacalaureat (Graduation): Corruption as Inheritance

Bacalaureat marks a shift toward contemporary urban Romania and explores a different kind of moral crisis: the quiet normalization of corruption.

The film centers on a father desperate to secure a better future for his daughter. When her chances are threatened, he begins making small compromises — favors, connections, moral shortcuts. None of them seem catastrophic on their own. Collectively, they form a devastating portrait of ethical erosion.

What makes Bacalaureat so powerful is its refusal to condemn its protagonist outright. Instead, Mungiu exposes how corruption often masquerades as pragmatism, how love can justify wrongdoing, and how entire systems sustain themselves through ordinary people choosing convenience over principle.

R.M.N. (2022): A Society Under the Microscope

R.M.N. may be Mungiu’s most overtly political film, yet it remains grounded in intimate human observation. Set in a multi-ethnic Transylvanian village, the film examines xenophobia, labor migration, and communal fear in contemporary Europe.

The title references a medical scan — a metaphor for what the film attempts to do: peer beneath the surface of polite coexistence and reveal the fractures beneath. Mungiu orchestrates group scenes with surgical precision, particularly a long town-hall sequence that feels less like cinema and more like a social autopsy.

In R.M.N., no one is entirely innocent, yet no one is reduced to caricature. Fear circulates freely — fear of outsiders, fear of loss, fear of irrelevance. Mungiu observes it all with the same moral steadiness that defines his entire body of work.

Cristian Mungiu’s Influence and Legacy

Cristian Mungiu did not merely become the most internationally recognized Romanian filmmaker of his generation; he reframed how Romanian cinema is perceived globally. His success helped draw attention to a broader movement, but his voice remains distinct — less stylistically flamboyant than some of his contemporaries, yet arguably more ethically penetrating.

Beyond Romania, Mungiu’s influence can be felt in the growing appreciation for slow, morally complex cinema that trusts audiences to engage deeply. His films remind us that realism need not be cold, and that restraint can be more devastating than excess.

Conclusion: A Belated Discovery Worth the Wait

Discovering Cristian Mungiu after years of overlooking Romanian cinema felt like uncovering a hidden wing of world cinema — one that had always been there, quietly waiting. His films do not seduce. They confront. They do not offer comfort. They demand reflection.

For a cinephile who once dismissed Romanian cinema as distant or inaccessible, Mungiu became a revelation. Through him, I learned that some of the most profound cinematic experiences are not found in spectacle, but in stillness, patience, and moral courage.

Cristian Mungiu’s cinema does not end when the screen goes dark. It stays with you — unresolved, unsettling, and unmistakably human.