There are filmmakers who push boundaries, and then there is Andrzej Żuławski—a Polish director who didn’t just cross cinematic lines but set them ablaze with operatic fury. For those of us wandering through the labyrinth of European arthouse cinema, seeking out the most uncompromising and eccentric auteurs, Żuławski stands as a towering, often terrifying figure. His films don’t merely demand attention; they assault the senses, leaving viewers exhilarated, exhausted, and fundamentally changed.

My own journey into Żuławski’s filmography began, as it does for many, with the cult phenomenon that is Possession. But to understand the full scope of this director’s achievement, one must dive deeper into a career marked by political persecution, aesthetic extremism, and an unwavering commitment to emotional authenticity taken to hysterical extremes.

The Making of a Cinematic Radical

Born in Lwów, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine) in 1940, Andrzej Żuławski came of age in a country still reeling from World War II’s devastation and firmly under Soviet influence. He studied cinema in France before returning to Poland, where he would create some of his earliest and most politically charged works. This geographical and political tension—between East and West, between artistic freedom and state censorship—would become a defining characteristic of his career and artistic vision.

Żuławski’s background in both Polish and French cinema gave him a unique perspective. He absorbed the formal experimentation of the French New Wave while maintaining the philosophical weight and historical consciousness of Eastern European cinema. Yet he transcended both traditions, creating something entirely his own: a cinema of possessed bodies, hysterical performances, and spaces that seem to warp under the pressure of human emotion.

The Żuławski Style: Aesthetics of Hysteria

Before examining individual films, we must understand what makes a Żuławski film immediately recognizable. His stylistic signatures are so distinctive that even a single frame can announce his authorship.

The Camera as Emotional Accomplice

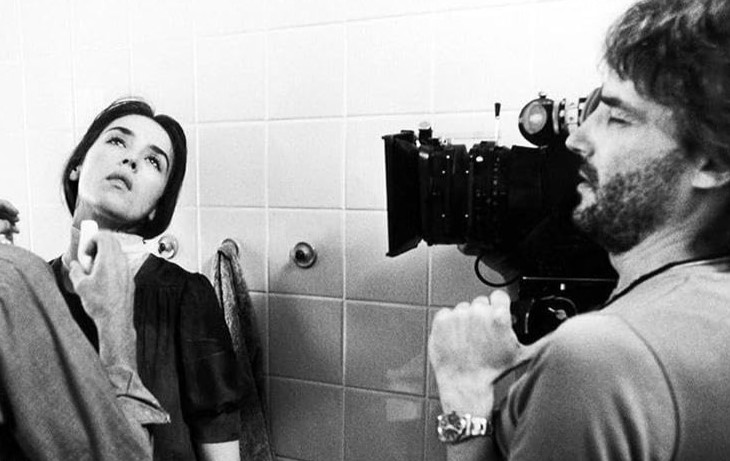

Żuławski’s camera never observes passively. It’s a participant in the emotional violence unfolding onscreen, employing restless, prowling movements that suggest a predator circling wounded prey. His cinematographers—most notably Bruno Nuytten on Possession and Andrzej J. Jaroszewicz on his Polish films—create tracking shots that follow characters through architectural spaces with an almost supernatural prescience, as if the camera knows where the emotional explosion will occur before the actors themselves do.

The fish-eye lenses, extreme close-ups, and vertiginous angles aren’t mere stylistic flourishes. They’re essential to Żuławski’s project of externalizing interior states. When a character’s world is collapsing, the physical world itself must appear to buckle and distort. His films exist in a constant state of visual emergency.

Performances on the Edge of Sanity

No discussion of Żuławski’s style can avoid his direction of actors. He pushed performers to the absolute limits of emotional endurance, demanding a level of commitment that many found traumatic. His actors don’t simply portray emotion; they seem to channel it directly from some raw, unmediated source.

The performances in Żuławski’s films are characterized by sudden shifts in register, from whispered tenderness to screaming rage within seconds. Characters laugh when they should cry, dance when they should flee. This creates a sense that we’re watching people whose emotional circuitry has been fundamentally rewired by trauma, obsession, or transcendence.

His regular collaborators—Romy Schneider, Isabelle Adjani, Sophie Marceau, and his wife Małgorzata Braunek—gave career-defining performances under his direction, often citing the experience as both the most challenging and rewarding of their careers.

Architectural Brutalism and Emotional Decay

Żuławski’s settings are never merely backdrops. The director had an uncanny ability to find locations—particularly examples of brutalist and modernist architecture—that seemed to embody psychological states. Empty apartments become prisons of the mind. Metro stations transform into liminal spaces where human identity dissolves. Even beautiful historical buildings take on a sinister quality, their elegance corrupted by the emotional violence they contain.

This is especially pronounced in Possession, where the sterile Berlin apartment and the decaying buildings near the Wall become physical manifestations of Mark and Anna’s disintegrating marriage.

The Early Polish Period: Rebellion and Censorship

The Third Part of the Night (1971)

Żuławski’s feature debut is not for the faint of heart. Set during the Nazi occupation of Poland, it follows a man whose family has been murdered joining a typhus research unit where human subjects are used to cultivate the disease in lice. The film is less a conventional war narrative than a hallucinatory descent into trauma and guilt.

Already, Żuławski’s mature style is visible. The camera refuses stable perspectives, events unfold in a nightmarish logic rather than linear narrative, and the protagonist seems to move through a world that’s fundamentally hostile to human meaning. The film draws on Żuławski’s father’s actual experiences during the war, giving it an autobiographical weight that intensifies its horror.

Critics were divided, but those who understood what Żuławski was attempting recognized the arrival of a significant new voice. This wasn’t cinema as entertainment or even as conventional art—it was cinema as exorcism.

The Devil (1972)

His follow-up examined political and religious oppression in 18th-century Poland through the story of a man imprisoned and tortured by a corrupt system. The parallels to contemporary Poland under Communist rule were obvious enough that authorities banned the film, and it wouldn’t be seen in its complete form until decades later.

The Devil shows Żuławski developing his interest in how power structures warp human behavior and identity. The film’s protagonist is broken down and reconstituted by his tormentors, a theme that would recur throughout Żuławski’s work: the self as something unstable, constantly under assault from external forces.

On the Silver Globe (1977-1988): The Interrupted Masterpiece

Here we arrive at one of cinema’s great tragedies and triumphs. Na srebrnym globie was Żuławski’s adaptation of his great-uncle Jerzy Żuławski’s science fiction trilogy about cosmonauts who crash-land on a distant planet and, over generations, create a new civilization that devolves into mysticism and tyranny.

Żuławski began filming in 1976 with massive ambition. The production was enormous by Polish standards, filmed in the Gobi Desert and the Caucasus Mountains, with elaborate costumes and makeup creating an alien world that feels genuinely otherworldly. The director was crafting nothing less than a creation myth, exodus narrative, and political allegory simultaneously—a grand statement about how humanity carries its capacity for both transcendence and oppression wherever it goes.

Then, in 1977, with the film approximately 80 percent complete, Polish authorities shut down production. The stated reason was economic, but the true motivation was almost certainly political. Żuławski’s uncompromising vision and the film’s obvious commentary on totalitarianism made it dangerous to the regime.

The director fled to France, and the incomplete footage sat in vaults for years. When Żuławski finally returned to Poland in the more liberal 1980s, he completed the film in a remarkable way: he filmed himself wandering through contemporary Poland with a handheld camera, narrating what the missing scenes would have shown. These documentary-style insertions are woven throughout the existing footage.

The result is unlike anything else in cinema. On the Silver Globe is simultaneously a completed film and a permanent fragment, a science fiction epic and a documentary about its own impossibility. The rough footage of 1980s Poland, with Żuławski’s voice describing scenes that were never filmed, creates a haunting meditation on artistic ambition, political oppression, and the gap between vision and reality.

The film’s ambition is staggering. The sequences that exist are visually overwhelming—tribal rituals in alien landscapes, elaborate costumes that suggest both primitiveness and sophistication, and performances of extraordinary intensity. The cosmonauts’ descendants create a religion around distorted memories of Earth, led by a Messiah figure whose teachings become increasingly tyrannical. It’s a story about how utopian visions inevitably curdle into oppression, told with operatic grandeur.

The narrative follows Jacek, the grandson of the original cosmonauts, who returns from Earth and becomes enmeshed in this society’s power struggles. His relationship with Aza, a woman from the planet’s indigenous population, provides the emotional core, but this is not a conventional romance. Like all Żuławski relationships, it’s marked by obsession, miscommunication, and the impossibility of true connection.

On the Silver Globe has achieved legendary status among cinephiles. It’s frequently cited alongside Jodorowsky’s unmade Dune and Welles’s unfinished projects as one of cinema’s great “what ifs,” though unlike those films, this one exists in a form that, while incomplete, is still experienceable and extraordinary. The film runs nearly three hours and demands complete submission to its fractured, mythic logic.

For those exploring Żuławski’s work, On the Silver Globe represents his most ambitious statement—a science fiction epic that’s really about Polish history, Catholic mysticism, colonial exploitation, and the human need to create meaning in a meaningless universe. It’s essential viewing, even in its compromised form.

Possession (1981): A Masterpiece of Marital Horror

And now we arrive at the film that has secured Żuławski’s place in cinema history: Possession, a work so extreme, so uncompromising in its vision that it remains shocking more than four decades after its creation.

On its surface, Possession tells a simple story: Mark (Sam Neill), a spy returning from an overseas assignment, discovers that his wife Anna (Isabelle Adjani) wants a divorce. She’s having an affair, she tells him, though the nature and extent of her infidelity become increasingly disturbing as the film progresses. As Mark investigates, he descends into obsession and violence, while Anna’s behavior becomes more erratic and inexplicable.

But Possession is not a domestic drama. It’s a horror film, a political allegory, a religious meditation, and a relationship autopsy all at once. Żuławski shot the film in West Berlin, with the Wall visible in many exterior shots—that concrete embodiment of division running through the city becomes a physical manifestation of the split between Mark and Anna, between past and present, between human and something beyond human.

The Performances That Defined an Era

Isabelle Adjani’s performance as Anna is legendary. She throws herself into the role with terrifying commitment, her body contorting, her voice shifting registers, her eyes reflecting genuine madness. The famous miscarriage scene in the subway—where Anna, fleeing from Mark, undergoes some kind of supernatural transformation—is one of cinema’s most disturbing sequences. Adjani writhes on the ground, screaming, bleeding, birthing something that we don’t yet understand. It’s not acting in any conventional sense; it’s something more primal.

Adjani later said the role was so emotionally demanding that she needed years to recover from it. She won the Best Actress award at Cannes, an acknowledgment that what she achieved went far beyond typical screen performance.

Sam Neill, primarily known for more conventional roles, matches Adjani’s intensity. His Mark is a man unraveling in real-time, his military bearing and masculine composure giving way to hysteria and violence. The scenes where Mark confronts Anna’s lover Heinrich (Heinz Bennent) are almost unbearable in their emotional nakedness—grown men screaming, weeping, reduced to wounded animals.

The Creature and the Doppelgängers

As the film progresses, it’s revealed that Anna has been visiting a rented apartment where she’s been caring for—and having sex with—a tentacled creature that she’s apparently creating through some kind of mystical process. The creature, designed by Carlo Rambaldi (who also created E.T.), is genuinely disturbing, all writhing flesh and inhuman anatomy.

Meanwhile, Mark begins a relationship with Helen, his son’s teacher, who is revealed to be a perfect double for Anna, played also by Adjani. The doubling extends further: the creature, as it evolves, begins to resemble Mark. These doppelgängers suggest that Mark and Anna are each trying to create idealized versions of their partner—versions that will perfectly satisfy their needs without the complications of actual human identity.

What Possession Is Really About

Interpretations of Possession are numerous and conflicting, which is part of its genius. Żuławski himself said the film was about his own divorce, an exorcism of the pain and rage he felt. The raw emotion certainly supports this reading—no one could fake the agony these characters express.

But the film also works as an allegory for the divided Berlin in which it’s set. The Wall running through the city, the spy plot that frames the narrative, the sense of a world split between two incompatible systems—all suggest that Mark and Anna’s failing marriage represents Cold War division, with the creature as the monstrous offspring of that unnatural separation.

Religious readings are equally valid. Anna’s creature could be a false god, something she worships in place of genuine faith or connection. The film’s imagery is full of Catholic symbolism—crucifixion poses, images of saints, discussions of faith and betrayal. Mark and Anna’s relationship has the quality of a religious crisis, a loss of faith in each other that mirrors a loss of faith in anything transcendent.

Some feminist critics have read the film as an exploration of female rage and autonomy—Anna’s creation of the creature could be seen as a rejection of patriarchal definitions of womanhood, a monstrous assertion of her own desire outside the bounds of marriage and motherhood.

The genius of Possession is that all these readings coexist. It’s a film that operates on multiple registers simultaneously, refusing to collapse into a single interpretation.

Style as Substance

The film’s visual style is quintessential Żuławski. Andrzej Korzyński’s score alternates between baroque classical pieces and discordant electronic sounds. Bruno Nuytten’s cinematography employs constant camera movement—tracking shots that circle characters, handheld sequences during moments of violence, sudden zooms that violate personal space.

The editing is deliberately jarring, with scenes ending abruptly or continuing past the point where conventional films would cut away. Time becomes elastic—we’re never quite sure how much time has passed between scenes, adding to the sense of reality breaking down.

The color palette is dominated by the blues and grays of Berlin’s architecture, with violent splashes of red (blood, Anna’s clothing) and the sickly flesh tones of the creature. Even before the horror elements emerge, the film’s world looks poisoned, corrupted.

Legacy and Influence

Possession was butchered for its American release, cut by nearly 40 minutes and marketed as a monster movie, where it predictably failed. European critics were divided—some recognized it as a masterpiece, others found it excessive and pretentious. But over the decades, its reputation has grown steadily.

Contemporary filmmakers from Gaspar Noé to Ari Aster have cited it as an influence. The body horror and relationship horror of films like Antichrist, Raw, and Titane owe clear debts to Żuławski’s masterpiece. Even the recent Crimes of the Future by Cronenberg echoes Possession‘s fusion of the visceral and the philosophical.

For many cinephiles, Possession represents the ultimate art-horror film—a work that uses genre elements not for conventional scares but to explore genuine existential terror. It’s a film that respects its audience’s intelligence while refusing to comfort them, demanding active interpretation while overwhelming the senses.

The French Period: Excess and Obsession

After Possession, Żuławski remained in France, where he would create a series of films exploring similar themes of obsession, identity, and the impossibility of genuine connection.

L’Amour braque (1985)

This adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, transposed to contemporary France, stars Sophie Marceau in a role that would begin a long collaboration with Żuławski. The film applies Żuławski’s feverish style to romantic melodrama, with characters pursuing impossible loves with self-destructive intensity.

Mes nuits sont plus belles que vos jours (1989)

Pairing Sophie Marceau with Jacques Dutronc, this science fiction-tinged romance involves a computer scientist dying from a brain tumor who begins a passionate affair with a real estate agent. The premise becomes a vehicle for Żuławski’s exploration of how we perform identity, with Dutronc’s character able to read minds and Marceau’s character constantly shifting personas.

La Fidélité (1992)

Another collaboration with Marceau, this contemporary update of Madame de La Fayette‘s 17th-century novel explores a photographer’s obsessive relationships. The film divides critics—some found Żuławski’s style perfectly suited to this portrait of contemporary alienation, others felt he was repeating himself.

Szamanka (1996)

A return to Poland resulted in this provocative film about an anthropology professor’s affair with a young woman who may be a witch or shaman. The film features explicit sex scenes that stirred controversy, but beneath the provocation lies Żuławski’s continued fascination with identity, possession, and the thin line between sanity and madness.

The Late Period: Refinement Without Compromise

La Femme publique (1984)

Often overlooked, this film about an actress (Valérie Kaprisky) starring in a film adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Possessed while her director (Lambert Wilson) becomes obsessively controlling is one of Żuławski’s most reflexive works. It’s simultaneously about the making of art and the cost of creation, with the theatrical and the real bleeding together until they’re indistinguishable.

Boris Godunov (1989)

Żuławski’s television film of Mussorgsky’s opera is rarely discussed but fascinating—his operatic directorial style finally applied to actual opera, creating something that feels like the platonic ideal of a Żuławski work.

Cosmos (2015)

His final film, adapted from Witold Gombrowicz’s novel, was completed when Żuławski was already seriously ill. It’s a fitting conclusion—a story about two men in a provincial guesthouse obsessively searching for patterns and meaning in random events. The film returns to Polish locations and the philosophical weight of his early work while maintaining the visual intensity of his entire career.

Some critics found Cosmos difficult or too faithful to Gombrowicz’s deliberately frustrating novel. But as a final statement, it’s perfect—Żuławski ending where he began, in Poland, with characters desperately seeking meaning in a universe that may be fundamentally meaningless.

The Żuławski Philosophy: Meaning Through Madness

Across all these films, certain themes recur obsessively. Żuławski’s characters are perpetually seeking—for meaning, for authentic connection, for transcendence. They pursue these goals with self-destructive intensity, and they invariably fail. Yet there’s something heroic in their failure, something admirable in their refusal to accept comfortable illusions.

His films suggest that madness might be the only honest response to existence. His characters who maintain composure and rationality are often the least trustworthy, while those who embrace hysteria at least have the virtue of authenticity. In Żuławski’s universe, extreme emotion is a form of truth-telling.

The director was also fascinated by performance and identity. His characters are constantly playing roles—spy, wife, teacher, artist—and these roles come to consume them. The question of whether there’s anything beneath the roles, any authentic self, haunts his films. His use of doppelgängers in Possession and elsewhere suggests that identity might be infinitely replicable, that the self is a performance rather than an essence.

Political Dimensions: Allegory and Resistance

Though Żuławski rejected simplistic political readings of his work, the political dimensions are undeniable. His experience of censorship in Poland, his filming of Possession in divided Berlin, his repeated explorations of power and tyranny—all indicate a consciousness deeply shaped by political reality.

His films from the Polish period are particularly loaded with political meaning. The Devil is obviously about totalitarianism and torture. On the Silver Globe explores how revolutionary movements become oppressive, how utopian visions justify violence. Even his later French films, seemingly focused on personal relationships, often include class dynamics and social commentary.

But Żuławski’s politics resist easy categorization. He was anti-authoritarian without being simplistically libertarian, critical of capitalism without endorsing socialism. His films suggest a profound pessimism about human social organization—every system, in his view, eventually becomes oppressive because humans themselves are fundamentally incapable of respecting others’ freedom and dignity.

Technical Mastery in Service of Vision

It’s worth emphasizing that Żuławski’s extremity wasn’t the result of technical incompetence or accidental excess. He was a master craftsman who chose to deploy his skills in service of overwhelming his audience.

His scripts, often co-written with his partner Frederic Tuten, are dense with literary and philosophical references. His use of music demonstrates sophisticated understanding—the Baroque pieces in Possession, the modernist compositions elsewhere. His collaborations with cinematographers produced some of the most visually distinctive work in European cinema.

The man could have made conventional, accessible films had he chosen to. His refusal to do so was an artistic and ethical choice—a belief that cinema should challenge and transform rather than comfort.

Influence and Legacy

Żuławski died in 2016, and his passing was mourned by cinephiles worldwide. His influence, already significant, has grown in the years since. The recent horror renaissance, with its emphasis on elevated or art-horror, owes enormous debts to his work.

Directors like Robert Eggers, Julia Ducournau, and Yorgos Lanthimos are working in territory Żuławski mapped decades earlier. The fusion of horror and relationship drama in recent films directly descends from Possession. The body horror of French extremity cinema follows paths he charted.

But his influence extends beyond horror. The emotional extremity of Lars von Trier, the formal experimentation of Gaspar Noé, the genre-defying ambition of contemporary arthouse cinema—all bear Żuławski’s mark.

For actors, his films remain touchstones of what’s possible in screen performance. The idea that you can push beyond naturalism into something more primal and true continues to inspire performers willing to take risks.

Why Żuławski Matters Now

In our contemporary moment, with its algorithmic smoothing of cultural rough edges and preference for easily consumable content, Żuławski’s films feel more necessary than ever. They cannot be passively consumed. They cannot be reduced to simple messages or comfortable interpretations. They demand engagement, patience, and a willingness to be genuinely challenged.

His work reminds us that cinema can be more than entertainment or even art in the conventional sense—it can be an experience that changes how we understand ourselves and our world. His films don’t provide answers; they don’t resolve into neat theses. Instead, they create spaces where questions can be asked with maximum intensity.

For those of us pursuing European cinema’s most uncompromising voices, Żuławski represents the standard against which others must be measured. He never compromised, never softened his vision, never sought easy accessibility. He made the films he needed to make, regardless of commercial considerations or critical reception.

Approaching Żuławski: A Viewer’s Guide

For newcomers to Żuławski’s work, I recommend starting with Possession. It’s his most accessible film—which admittedly isn’t saying much—and the one that best encapsulates his themes and style. Watch it with the best sound system you can access; the film’s audio design is crucial.

From there, On the Silver Globe offers a very different but equally essential perspective on his work. The contrast between these two films—one claustrophobic and contemporary, one epic and mythic—demonstrates his range.

The early Polish films reward viewers willing to engage with their difficulty. The Third Part of the Night especially deserves more attention than it typically receives.

The French period is less essential but contains gems for those already committed to Żuławski’s vision. L’Amour braque and La Femme publique are probably the most approachable of these.

Throughout, remember that confusion and discomfort are part of the experience. Żuławski’s films aren’t puzzles to be solved but provocations to be experienced. Allow yourself to be overwhelmed. Resist the urge to pin down definitive meanings. Embrace the hysteria.

Conclusion: The Fevered Dream Continues

Andrzej Żuławski crafted a cinema unlike anyone else’s—films that exist in a perpetual state of emotional emergency, where reality bends under the pressure of human feeling, where the only honest response to existence is a scream. His work challenges every comfortable assumption about what cinema should be or do.

For those of us who believe that art should disturb, provoke, and transform rather than merely entertain, Żuławski’s films represent a pure distillation of cinema’s potential. They remind us that the medium can access dimensions of human experience that other art forms cannot reach, that the combination of performance, image, sound, and movement can create something genuinely transcendent.

His influence continues to ripple through contemporary cinema, felt in films that dare to push boundaries and refuse easy consumption. But more importantly, his actual films remain there, waiting to be discovered by each new generation of viewers willing to submit to their particular intensity.

In an era of algorithmic recommendation and content optimization, Żuławski’s cinema offers the opposite: films that cannot be easily categorized, that resist passive consumption, that demand everything from their viewers and offer in return not comfort but something rarer and more valuable—the shock of genuine artistic vision, uncompromised and uncompromising.

For those of us on this perpetual journey through European cinema’s most eccentric and essential voices, Żuławski stands as a reminder of what’s possible when a filmmaker refuses every limitation and pursues their vision with absolute commitment. His films are difficult, disturbing, and occasionally unbearable. They’re also absolutely necessary. In the controlled chaos of his cinema, we encounter not just one man’s vision but something larger—a reflection of the madness, beauty, and terror of existence itself.

The fever dream continues, waiting for anyone brave enough to enter.