Introduction: The Master of Iranian Cinema

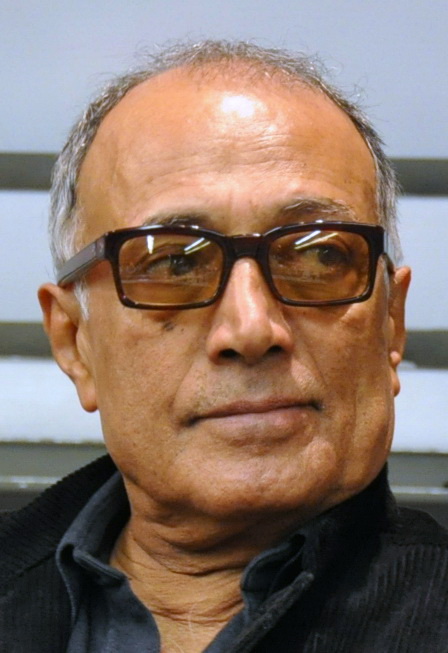

Abbas Kiarostami (1940–2016) remains one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema, not just within Iran but across the global cinematic landscape. His films, characterized by their poetic minimalism, philosophical depth, and innovative narrative structures, have left an indelible mark on world cinema. Kiarostami’s work transcends conventional storytelling, blending reality and fiction in ways that challenge viewers to engage deeply with the medium.

His influence extends to legendary directors like Andrei Tarkovsky and Robert Bresson, though interestingly, Kiarostami himself was also shaped by their works, creating a reciprocal artistic dialogue. This article explores Kiarostami’s unique style, his thematic preoccupations, his major films, his legacy, and his impact on cinema—both as an influencer and as someone influenced by the greats who came before him.

1. The Evolution of Kiarostami’s Style

1.1. Early Works and Documentary Influences

Kiarostami began his career in the 1960s as a graphic designer and illustrator before moving into filmmaking. His early work at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) shaped his approach, emphasizing simplicity, authenticity, and a focus on young protagonists.

Films like The Bread and Alley (1970) and The Traveler (1974) showcase his early style—naturalistic performances, non-professional actors, and a keen observation of everyday life. His documentary-like approach blurred the line between fiction and reality, a technique he would refine throughout his career.

1.2. The Koker Trilogy: A Turning Point

The Koker Trilogy—comprising Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987), And Life Goes On (1992), and Through the Olive Trees (1994)—marked a significant evolution in Kiarostami’s style. These films, set in the rural Koker region after a devastating earthquake, intertwine fiction and reality, often breaking the fourth wall.

- Where Is the Friend’s House? is a deceptively simple story about a boy trying to return his friend’s notebook, but it carries profound themes of duty and moral responsibility.

- And Life Goes On (also known as Life and Nothing More) follows a filmmaker (a stand-in for Kiarostami) searching for the child actors from the first film after the earthquake, blending documentary and fiction.

- Through the Olive Trees further deconstructs filmmaking by depicting the making of And Life Goes On, creating layers of meta-narrative.

This trilogy exemplifies Kiarostami’s fascination with the nature of cinema itself—how stories are constructed, how reality is framed, and how viewers engage with the medium.

1.3. The Palme d’Or and International Acclaim: Taste of Cherry (1997)

Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, is a meditative exploration of life and death. The film follows a man driving through the Iranian countryside, seeking someone to bury him after his planned suicide. The minimalist dialogue, long takes, and open-ended conclusion epitomize Kiarostami’s style—inviting contemplation rather than providing easy answers.

1.4. Later Works: Experimentation and Digital Cinema

In his later years, Kiarostami embraced digital filmmaking, experimenting with form in films like Ten (2002), shot entirely inside a car with fixed cameras, and Certified Copy (2010), a European production starring Juliette Binoche that plays with the concept of authenticity in art and relationships. His final film, 24 Frames (2017), released posthumously, is a series of meticulously composed vignettes, each based on a single photograph—a fitting farewell from a director who always sought to capture the poetry in stillness.

2. Kiarostami’s Vision: Themes and Philosophical Underpinnings

2.1. The Blurring of Reality and Fiction

Kiarostami’s films often dissolve the boundaries between documentary and fiction. He frequently used non-actors, improvised dialogue, and real locations, creating a sense of authenticity. Yet, he also reminded viewers of the constructed nature of cinema, as seen in Close-Up (1990), where he reenacts the true story of a man who impersonated filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

2.2. The Journey as Metaphor

Many of Kiarostami’s films revolve around journeys—both physical and existential. The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) follows an engineer traveling to a remote village, while Taste of Cherry is a literal and metaphorical road movie about mortality. These journeys reflect broader philosophical inquiries into human existence, purpose, and perception.

2.3. The Role of the Viewer

Kiarostami believed in an active viewer. His open-ended narratives (like the ambiguous finale of Taste of Cherry) require audience participation to derive meaning. He often denied easy resolutions, forcing viewers to engage with uncertainty—an approach influenced by Persian poetry, which values suggestion over explicit statement.

2.4. Nature and Human Connection

Landscapes play a crucial role in Kiarostami’s films. The winding roads of Koker, the barren hills in The Wind Will Carry Us, and the autumnal trees in Taste of Cherry are not just backdrops but active elements that shape the narrative. His framing of nature evokes a sense of solitude, contemplation, and the sublime.

3. Kiarostami’s Influence on Andrei Tarkovsky and Robert Bresson

3.1. The Mutual Respect Between Kiarostami and Tarkovsky

Though Kiarostami emerged after Tarkovsky’s prime, the Russian filmmaker admired his work, famously saying, “Kiarostami is the greatest example of how one can resist the vulgarity of the modern world.” Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975) and Stalker (1979) share Kiarostami’s contemplative pacing and poetic imagery. Both directors explored spiritual and metaphysical themes, though Kiarostami’s approach was more grounded in realism.

3.2. Kiarostami and Bresson: Minimalism and Precision

Robert Bresson’s influence on Kiarostami is evident in their shared austerity. Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) and A Man Escaped (1956) employ minimal dialogue, restrained performances, and a focus on small, meaningful details—qualities Kiarostami refined in his own films. Both directors believed in “pure cinema,” where images and sounds carry more weight than exposition.

However, Kiarostami diverged from Bresson’s rigid formalism by incorporating more spontaneity, often allowing real-life unpredictability to shape his narratives.

4. Kiarostami’s Legacy and Global Impact

4.1. Inspiring a New Wave of Iranian Cinema

Kiarostami paved the way for Iranian filmmakers like Jafar Panahi, Asghar Farhadi, and Majid Majidi, who adopted his realist techniques while developing their own voices. His success also brought international attention to Iranian cinema, proving that profound storytelling could thrive despite political constraints.

4.2. Influence on World Cinema

Directors such as Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Carlos Reygadas have cited Kiarostami as a major influence. His emphasis on slow cinema, naturalism, and philosophical depth resonates in contemporary art-house films.

4.3. Beyond Film: Poetry, Photography, and Installation Art

Kiarostami was also a poet and photographer, and his visual artistry extended to gallery exhibitions. His multidisciplinary approach reinforced his belief in the interconnectedness of all art forms.

Conclusion: The Eternal Poet of Cinema

Abbas Kiarostami’s films are not just watched—they are experienced. His ability to find profundity in simplicity, to merge reality with artifice, and to engage viewers as active participants makes him one of cinema’s true visionaries. Though he has passed, his legacy endures in every filmmaker who dares to see the world with poetic clarity. As Jean-Luc Godard once said, “Cinema begins with D.W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami.”

His work remains a testament to the power of cinema as a medium of contemplation, connection, and timeless beauty.

Pingback: The Koker Trilogy: Abbas Kiarostami’s Humanist Cinema in the Rubble of Reality - deepkino.com