There are filmmakers who try to understand their country, and there are filmmakers who are wounded by it. Aleksey Balabanov belonged firmly to the latter category. His cinema does not observe Russia from a distance, nor does it mythologize it with comforting nostalgia. Instead, it drags the viewer into the moral rubble left behind by history, ideology, and violence. Watching Balabanov is not a pleasant experience, but it is a necessary one — especially for anyone fascinated by the darker, more uncomfortable depths of Russian cinema.

Balabanov was not interested in beauty for its own sake, nor in redemption as a narrative obligation. His films are heavy with guilt, brutality, and moral exhaustion. They feel lived-in, scarred, and deeply personal, as though each work was created not to entertain, but to survive. In that sense, Balabanov stands closer to Dostoevsky than to conventional genre filmmakers: his cinema interrogates the soul at its breaking point.

A Director Formed by Collapse

Born in Sverdlovsk in 1959, Balabanov came of age during the late Soviet period — a time already marked by stagnation, quiet despair, and ideological decay. Unlike filmmakers shaped by post-war optimism or artistic liberalization, Balabanov’s formative years were steeped in disillusionment. His military service further stripped away illusions, exposing him to institutional violence and the emptiness behind authority.

This background matters. Balabanov’s films do not merely depict violence; they understand it as systemic, banal, and deeply internalized. His characters rarely question the morality of their actions — not because they are monsters, but because moral language itself has collapsed. This is the emotional climate of post-Soviet Russia, and Balabanov captured it with an honesty that few dared to approach.

Brat: The Birth of a Broken Hero

Brat (1997) arrived at precisely the moment Russia needed — and feared — such a film. On the surface, it is a crime story: a young man, Danila Bagrov, arrives in Saint Petersburg and drifts into the criminal underworld. But Brat is not really about crime. It is about orientation. About a generation searching for rules in a world where none seem to exist anymore.

Danila is not a traditional hero. He is quiet, emotionally opaque, and capable of extreme violence without hesitation. Yet he is also sincere, loyal, and almost childlike in his sense of justice. Balabanov never explains Danila psychologically; instead, he lets him exist as a symptom of his time. This ambiguity is crucial. Brat does not ask us to admire Danila — it asks us to recognize him.

The film’s use of Russian rock music, urban landscapes, and everyday spaces gives it a documentary-like authenticity. Saint Petersburg is not romanticized; it is cold, indifferent, and morally unstable. In Brat, Balabanov created not only a cult character, but a cultural mirror — one that reflected the confusion, anger, and fragile pride of post-Soviet youth.

Brat 2: National Identity in a Global Void

If Brat was about survival, Brat 2 (2000) is about confrontation — with the outside world, with capitalism, and with Russia’s own unresolved identity. Sending Danila abroad was a bold move, and one that transformed the sequel into something far more complex than a simple continuation.

Here, Balabanov sharpens his satire. America is not portrayed as an enemy, nor as a dreamland, but as another morally hollow system driven by money and power. Danila’s naïve sense of justice clashes with global reality, exposing both the absurdity and the danger of simplistic moral codes.

What makes Brat 2 remarkable is its tonal instability. It shifts between action, irony, nationalism, and melancholy without ever settling comfortably. Balabanov understood that the Russia of the early 2000s was itself unstable — torn between resentment, aspiration, and unresolved trauma. The film’s enduring popularity speaks less to ideology than to emotional truth.

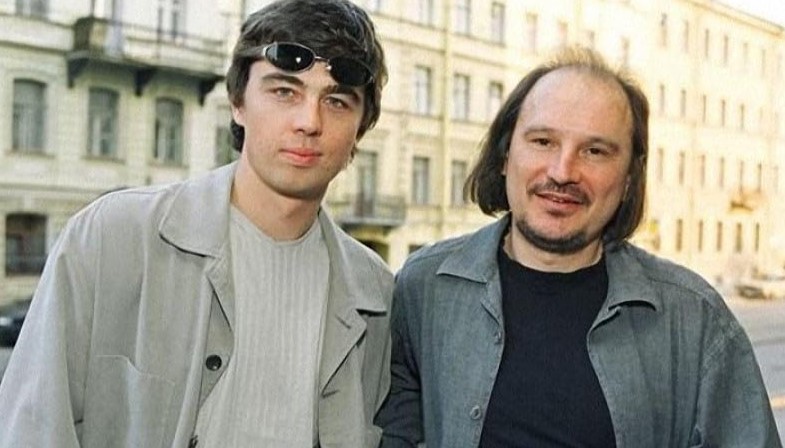

Sergey Bodrov Jr.: A Face of a Generation

It is impossible to separate Balabanov’s legacy from his collaboration with Sergey Bodrov Jr. Their fruitful bond was rare and deeply organic. Bodrov possessed a unique screen presence — introspective, restrained, and quietly magnetic. He did not perform Danila; he inhabited him.

Balabanov trusted Bodrov completely, allowing silence, hesitation, and contradiction to exist on screen. This trust elevated both men’s work. Together, they created one of Russian cinema’s most enduring figures — not a hero to emulate, but a figure to grapple with.

Bodrov’s tragic death in 2002 marked a rupture not only in Russian cinema, but in Balabanov’s inner world. While Balabanov never turned grief into public spectacle, the shadow of loss is unmistakable in his later films. Guilt, death, and moral exhaustion become heavier, more oppressive. Cinema, for Balabanov, was no longer just a reflection of reality — it was a burden he carried.

Pro urodov i lyudey: The Perverse Origins of Modernity

With Pro urodov i lyudey (Of Freaks and Men), Balabanov turned backward in time — but only to expose the roots of contemporary moral decay. Set in early 20th-century Russia, the film explores voyeurism, exploitation, and the commodification of the human body through early pornography.

Stylistically, it is one of Balabanov’s most daring works. The sepia tones and silent-era aesthetics are not nostalgic; they are unsettling. The past, in Balabanov’s hands, is not innocent. It is already corrupt, already obsessed with control and spectacle.

This film reveals a crucial aspect of Balabanov’s worldview: modern brutality did not appear suddenly in the 1990s. It evolved. It matured. It learned how to disguise itself.

Zhmurki: Violence as Absurd Performance

Zhmurki (Dead Man’s Bluff) often surprises viewers familiar only with Balabanov’s darker works. On the surface, it is loud, chaotic, and comedic — a grotesque parody of gangster cinema. But beneath the surface, Zhmurki is one of Balabanov’s most cynical films.

Here, violence becomes farce. Death is random, meaningless, and often played for laughs. Characters kill not out of ideology or desperation, but habit. This is Balabanov diagnosing a culture that has become numb — where brutality has lost even its tragic weight.

The film’s humor is cruel, but deliberate. Balabanov is not entertaining the audience; he is exposing how easily violence can be normalized when history offers no moral anchor.

Gruz 200: Cinema at Its Most Merciless

Gruz 200 is perhaps Balabanov’s most controversial and devastating work. Set in the dying days of the Soviet Union, it portrays a world rotten to its core — not metaphorically, but viscerally. Corruption, sexual violence, moral collapse, and bureaucratic cruelty coexist without hierarchy.

This is not a film that offers catharsis. It suffocates. Balabanov strips away all illusions: nostalgia for the Soviet past, belief in authority, faith in progress. Gruz 200 suggests that the seeds of post-Soviet brutality were already present long before the system collapsed.

Many viewers reject the film, and that rejection is understandable. But for those willing to endure it, Gruz 200 stands as one of the most honest indictments of systemic evil in modern cinema.

Kochegar: The Quiet Weight of Guilt

By the time Balabanov made Kochegar (A Stoker), his cinema had grown quieter — but not gentler. The film centers on an aging man whose job is to burn bodies for the mafia. He performs his task mechanically, almost ritualistically, as though trying to erase himself.

Kochegar is a film about complicity. About how evil survives not through monsters, but through ordinary people who keep things running. The stoker is not sadistic. He is tired. And that exhaustion — moral, physical, existential — defines Balabanov’s late period.

Style: Anti-Romantic, Anti-Illusion

Balabanov’s visual style rejects ornamentation. His camera observes rather than embellishes. Violence is rarely stylized; it is abrupt, uncomfortable, and often emotionally hollow. Music, when used, functions as cultural memory rather than emotional manipulation.

His cinema exists in dialogue with Russian literary pessimism and Soviet disillusionment, but it is not nostalgic. Balabanov does not mourn lost ideals — he interrogates why they failed.

Death, Guilt, and an Unfinished Journey

Balabanov died in 2013 at the age of 54, leaving behind a body of work that feels both complete and painfully unfinished. His later years were marked by declining health and a visible emotional burden. The loss of Bodrov never left him; it lingered, silently shaping his worldview.

There is something tragically fitting about Balabanov’s early death. His cinema never suggested longevity or peace. It was forged in tension, conflict, and unresolved grief.

Legacy: A Cinema That Refuses Comfort

Today, Aleksey Balabanov stands as one of the most essential figures in Russian cinema — not because he was beloved, but because he was honest. His films continue to divide audiences, provoke debate, and resist easy classification.

For cinephiles drawn to Russian cinema not as exoticism but as moral inquiry, Balabanov is unavoidable. His work demands engagement, endurance, and reflection. It does not offer solutions — only truth, however unbearable that truth may be.