Introduction

Cinema Novo, meaning “New Cinema,” emerged in Brazil in the late 1950s and flourished through the 1960s and 1970s. Much more than a cinematic style, it was a cultural and political movement that challenged both aesthetic norms and social injustices. Strongly influenced by Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave, Cinema Novo became the voice of the marginalized, the poor, and the oppressed in Brazilian society. It was a call to arms against imperialism, poverty, and the escapism of commercial cinema.

With roots in a tumultuous political landscape and deep social inequality, Cinema Novo redefined not only Brazilian cinema but also the relationship between art and politics. This article will examine the origins, stylistic characteristics, key figures, phases, and legacy of Cinema Novo.

Historical and Political Context

Brazil in the mid-20th century was marked by deep disparities between rich and poor, urban elites and rural peasants, and a ruling class resistant to social reform. The country experienced intense political fluctuations, including the populist government of Getúlio Vargas, the conservative backlash that followed, and the 1964 military coup that led to a dictatorship.

The Brazilian film industry, until then, had largely been dominated by escapist fare. Studios like Atlântida churned out popular comedies and musicals, offering fantasy rather than reflecting the harsh realities of life for most Brazilians. Cinema Novo emerged as a radical alternative. It sought to depict the “aesthetics of hunger”—a term coined by Glauber Rocha—by portraying poverty, underdevelopment, and the resilience of the Brazilian people.

Origins and Philosophical Foundations

The genesis of Cinema Novo can be traced to the late 1950s and early 1960s when a group of young filmmakers began to rebel against the artificiality and commercialism of mainstream Brazilian cinema. They were deeply influenced by:

- Italian Neorealism: With its emphasis on non-professional actors, location shooting, and social themes.

- French New Wave: With its experimental techniques and emphasis on auteur filmmaking.

- Marxist Theory: Especially the belief that cinema should be an instrument of social critique.

These filmmakers—many of whom came from middle-class backgrounds and were university-educated—believed that cinema should serve a national and political purpose. It should show the Brazil that had been ignored or distorted in popular culture.

The Aesthetics of Hunger

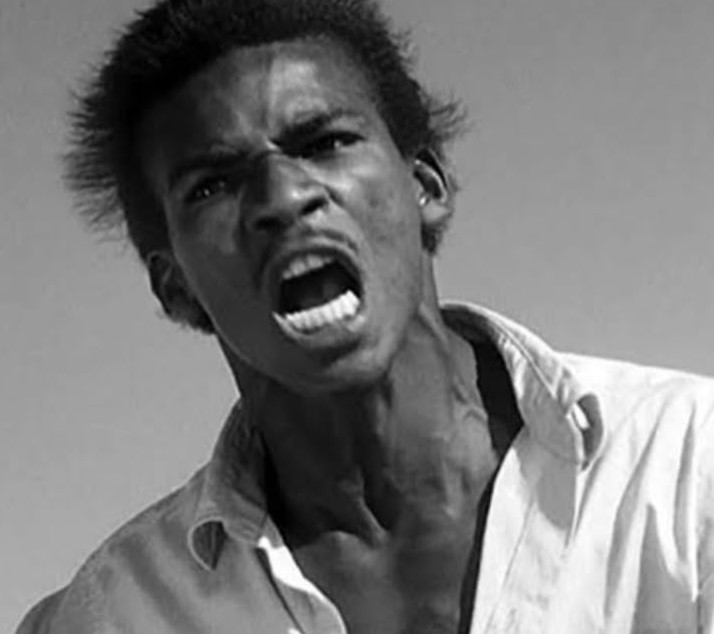

Glauber Rocha, arguably the most influential figure of the movement, wrote in his seminal essay “An Aesthetics of Hunger” (1965) that the misery of Latin America should not be hidden or beautified. Instead, it should be embraced as a source of artistic and political expression. According to Rocha:

“Only when we are able to accept—without shame—our condition of hungry beings, will we be able to create a revolutionary cinema.”

This aesthetic manifested through:

- Handheld cameras and rough editing

- Natural lighting and on-location shooting

- Non-professional actors and real settings

- Symbolism and surreal imagery to highlight political oppression

Cinema Novo films did not aim to entertain but to provoke. They were a form of protest against both foreign imperialism and domestic corruption.

Phases of Cinema Novo

Cinema Novo is generally divided into three phases:

First Phase (1960–1964): The Awakening

This phase emphasized realism and social critique. Influenced by neorealism, the films focused on rural poverty, class struggle, and the need for revolution. Key works include:

- “Barravento” (1962) by Glauber Rocha: Set in a fishing village, the film addresses Afro-Brazilian traditions and class oppression.

- “Vidas Secas” (1963) by Nelson Pereira dos Santos: Based on Graciliano Ramos’s novel, it captures the despair of a peasant family in the drought-stricken Northeast.

- “Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol” (Black God, White Devil, 1964) by Glauber Rocha: A revolutionary film that blends realism with religious allegory.

Second Phase (1964–1968): Radicalization

After the 1964 military coup, Cinema Novo became more allegorical and stylistically experimental. The censorship that followed the coup forced filmmakers to encode their political critiques in symbolism and metaphor.

- “Terra em Transe” (Entranced Earth, 1967) by Glauber Rocha: A political allegory exploring the manipulation of power in a fictional Latin American country.

- “O Desafio” (The Challenge, 1965) by Paulo César Saraceni: Depicts the conflict between revolution and complacency.

- “O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro” (Antonio das Mortes, 1969) by Glauber Rocha: A psychedelic Western exploring themes of messianism and justice.

Third Phase (1968–1972): Fragmentation and Commercialization

As state repression increased and censorship became stricter, Cinema Novo began to decline. Some filmmakers moved into more commercial territory, others left the country, and some transitioned into television and theater. The radical core of the movement dissipated, but its spirit endured.

Key Figures

Glauber Rocha

Rocha was the intellectual and spiritual leader of Cinema Novo. His fusion of revolutionary politics and avant-garde aesthetics made him a polarizing but crucial figure. His films, essays, and activism defined the movement’s ideological core.

Nelson Pereira dos Santos

A pioneer who laid the groundwork for Cinema Novo, his film Rio 40 Graus (1955) was a precursor to the movement. His later works like Vidas Secas became milestones in political cinema.

Ruy Guerra

A Mozambican-born director who contributed key works like Os Fuzis (The Guns, 1964), which portrays a confrontation between soldiers and starving peasants.

Leon Hirszman and Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

Both contributed significantly to the movement’s diversity in style and theme. Andrade’s Macunaíma (1969) introduced satirical and surreal elements, while Hirszman’s São Bernardo (1972) explored capitalist alienation.

Legacy and Influence

Cinema Novo profoundly influenced not only Latin American cinema but also global cinematic movements. Its legacy can be traced through:

- Tropicalismo and Marginal Cinema: These movements built upon the foundation of Cinema Novo by embracing even more radical forms.

- Contemporary Brazilian Directors: Filmmakers like Kleber Mendonça Filho (Aquarius, Bacurau) and Anna Muylaert (The Second Mother) inherit its social critique.

- Global Impact: Its emphasis on auteurship, social justice, and anti-colonial narratives inspired filmmakers across Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe.

The movement also inspired a wave of academic studies and retrospectives, keeping its ideals alive in the discourse of world cinema.

Criticisms and Limitations

Despite its achievements, Cinema Novo faced criticism for several reasons:

- Accessibility: Its allegorical style and avant-garde techniques often alienated general audiences.

- Representation: While it aimed to depict the poor, critics argue it sometimes did so through a paternalistic lens.

- Gender Issues: Women were often sidelined or portrayed in stereotypical roles.

However, these critiques also prompted important dialogues within Brazilian society and the global film community, pushing the boundaries of what political cinema could be.

Conclusion

Cinema Novo was not just a cinematic revolution; it was a political and cultural insurgency that redefined the purpose and power of film. In a nation plagued by inequality, dictatorship, and cultural domination, these filmmakers dared to imagine a cinema that could be both beautiful and revolutionary. They saw film as a weapon of liberation—a mirror held up to a fractured nation.

Through its powerful visual language and uncompromising commitment to social justice, Cinema Novo left an indelible mark on both Brazilian and global cinema. It remains a potent example of how art can confront power, and how the stories of the oppressed can become the foundation for a more equitable and humane cinematic tradition.