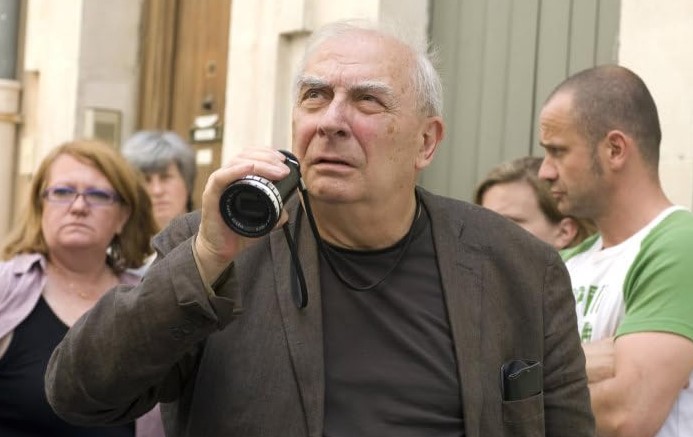

Claude Chabrol (1930-2010) stands as one of the most prolific and influential directors of the French New Wave movement, earning recognition as a master craftsman who bridged the gap between classical Hollywood cinema and modernist European filmmaking. Over a career spanning more than five decades, Chabrol directed over 50 films, establishing himself as France’s premier chronicler of bourgeois psychology and social dynamics. His meticulous attention to character development, sophisticated understanding of genre conventions, and keen eye for the dark undercurrents of middle-class life made him both a commercial success and a critical darling throughout his extensive career.

Early Life and Formation

Born on June 24, 1930, in Sardent, a small commune in the Creuse department of central France, Claude Henri Jean Chabrol grew up in a middle-class family that would later provide rich material for his cinematic explorations. His father was a pharmacist, and his mother came from a bourgeois background—circumstances that gave young Claude intimate knowledge of the social milieu he would later dissect with surgical precision in his films.

Chabrol’s path to cinema began during his university years in Paris, where he studied literature and law at the Sorbonne. However, his true passion lay in film, and he became a regular attendee at the Cinémathèque Française, where he encountered the works of international masters and developed his sophisticated understanding of cinema history. It was during this period that he began writing film criticism for Cahiers du Cinéma, the influential magazine founded by André Bazin that would become the intellectual breeding ground for the French New Wave movement.

As a critic, Chabrol demonstrated the analytical rigor and deep appreciation for cinema that would characterize his directorial work. He wrote extensively about American directors like Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Fritz Lang, developing particular admiration for Hitchcock’s mastery of suspense and psychological complexity. This influence would prove crucial in shaping Chabrol’s own directorial style, earning him the moniker “the French Hitchcock” throughout his career.

The Birth of the New Wave

Chabrol played a pivotal role in launching the French New Wave movement, becoming the first of the Cahiers du Cinéma critics to transition successfully to feature filmmaking. In 1958, he directed “Le Beau Serge” (Bitter Reunion), which is widely considered the first true New Wave film. The project was made possible by an inheritance from his first wife, allowing him the financial independence to create cinema on his own terms.

“Le Beau Serge” exemplified the New Wave’s revolutionary approach to filmmaking. Shot on location in Sardent, Chabrol’s hometown, the film employed natural lighting, handheld cameras, and non-professional actors alongside established performers. The story of a young man returning to his provincial hometown to help his alcoholic childhood friend demonstrated Chabrol’s interest in psychological realism and social observation that would define his career.

The film’s success was followed immediately by “Les Cousins” (The Cousins) in 1959, which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. These early works established Chabrol as a major voice in international cinema and helped define the aesthetic and thematic concerns of the New Wave movement. Unlike some of his contemporaries who would later abandon or modify their New Wave principles, Chabrol remained committed throughout his career to the movement’s emphasis on personal authorship, location shooting, and intimate character studies.

Directorial Style and Cinematic Philosophy

Chabrol’s directorial style was characterized by its sophisticated blend of classical narrative techniques and modernist sensibilities. He possessed an exceptional ability to work within genre conventions while simultaneously subverting them, creating films that satisfied both popular audiences and critical observers. His visual style was notably restrained and elegant, favoring carefully composed shots and subtle camera movements over flashy techniques.

One of Chabrol’s greatest strengths was his direction of actors. He had an remarkable ability to draw naturalistic performances from his cast, often working repeatedly with the same performers who understood his methods and vision. His films featured extended dialogue scenes that revealed character through conversation and behavior rather than exposition, requiring actors who could convey psychological complexity through subtle means.

Chabrol’s color palette and production design consistently reflected his themes. He often employed warm, muted tones to create an atmosphere of bourgeois comfort that masked underlying tensions and conflicts. His attention to domestic details—furniture, clothing, food, and social rituals—provided rich visual context that reinforced his psychological explorations. These elements combined to create what critics have termed “Chabrolian” cinema: psychologically acute, visually sophisticated, and thematically complex.

The director’s approach to suspense was heavily influenced by Alfred Hitchcock, but Chabrol developed his own distinctive methods. Rather than relying on external threats or elaborate plot mechanisms, he generated tension through character relationships and social dynamics. His suspense emerged from the psychological pressures within seemingly normal situations, making his films particularly unsettling because they suggested that danger and corruption could emerge from the most ordinary circumstances.

Major Works and Career Highlights

The Breakthrough Period (1958-1962)

Following his initial successes, Chabrol continued to establish his reputation with a series of films that explored different aspects of French society. “À double tour” (Web of Passion, 1959) was his first film in color and demonstrated his growing visual sophistication. “Les Bonnes Femmes” (The Good Time Girls, 1960) examined the lives of young working women in Paris, combining social observation with psychological insight in a way that would become characteristic of his mature work.

The Commercial Period (1962-1967)

During the mid-1960s, Chabrol made several commercially oriented films that allowed him to refine his craft while maintaining his independence. Works like “The Tiger Loves Fresh Meat” (1964) and “Our Agent Tiger” (1965) were commercial thrillers that demonstrated his versatility, though critics sometimes dismissed them as compromises to his artistic vision. However, these films allowed Chabrol to experiment with different genres and maintain the financial stability necessary for his more personal projects.

The Mature Masterpieces (1968-1975)

The late 1960s marked the beginning of Chabrol’s most celebrated period. “Les Biches” (The Does, 1968) established his collaboration with actress Stéphane Audran, who became both his creative partner and his wife. The film’s exploration of a ménage à trois among wealthy characters in St. Tropez demonstrated Chabrol’s mastery of psychological complexity and social observation.

“The Butcher” (Le Boucher, 1970) is widely considered Chabrol’s masterpiece and one of the finest achievements of the New Wave movement. Set in a small village in Périgord, the film tells the story of a subtle relationship between a schoolteacher (Stéphane Audran) and a local butcher (Jean Yanne) against the backdrop of a series of murders. The film’s exploration of violence, desire, and social respectability exemplifies Chabrol’s ability to find profound themes in simple stories.

“Just Before Nightfall” (Juste avant la nuit, 1971) continued his examination of bourgeois morality through the story of a man who confesses to murdering his mistress. “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” period also saw “Wedding in Blood” (Les Noces rouges, 1973), which examined adultery and murder among middle-class characters with characteristic psychological acuity.

Later Career and Continued Excellence (1976-2010)

Chabrol’s later career demonstrated remarkable consistency and continued innovation. “Violette Nozière” (1978) starred Isabelle Huppert as a real-life figure who poisoned her parents, beginning a significant collaboration between director and actress that would span multiple films. Huppert became one of Chabrol’s most important interpreters, appearing in eight of his films and bringing psychological complexity to his exploration of female characters.

“Story of Women” (Une affaire de femmes, 1988) reunited Chabrol with Huppert in the story of a woman executed for performing abortions during World War II. The film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and demonstrated Chabrol’s continued ability to find contemporary relevance in historical subjects.

“La Cérémonie” (1995), another collaboration with Huppert alongside Sandrine Bonnaire, examined class conflict through the story of domestic servants who turn against their employers. The film won the Golden Lion at Venice and proved that Chabrol’s insights into social dynamics remained sharp and relevant.

His final films, including “The Flower of Evil” (La Fleur du mal, 2003) and “A Girl Cut in Two” (La Fille coupée en deux, 2007), continued to explore his characteristic themes with undiminished skill and psychological insight.

Exploration of Bourgeois Psychology

Perhaps no filmmaker has examined the French bourgeoisie with greater insight and consistency than Claude Chabrol. His films function as a comprehensive sociology of middle-class life, revealing the psychological tensions, moral compromises, and social pressures that define bourgeois existence. Chabrol understood that the bourgeoisie’s emphasis on respectability, material comfort, and social status created ideal conditions for psychological drama.

His characters typically inhabit comfortable domestic spaces—well-appointed homes, country estates, resort locations—that serve as stages for psychological conflicts. These settings provide visual contrast to the emotional turmoil experienced by his characters, suggesting that material comfort cannot provide psychological security or moral clarity. Chabrol’s bourgeois characters are often trapped by their own success, unable to escape the social expectations and personal compromises that define their lives.

The director’s treatment of marriage and family relationships was particularly acute. His films repeatedly examine how intimate relationships can become sources of tension, resentment, and violence when combined with social pressures and individual psychological needs. Characters in Chabrol films often lead double lives, maintaining respectable facades while harboring secret desires, resentments, and moral failures.

Money plays a crucial role in Chabrol’s psychological explorations. His characters’ relationship to wealth, property, and financial security often drives their actions and reveals their true natures. The director understood that financial considerations could corrupt personal relationships and moral decision-making, making bourgeois comfort a source of anxiety rather than satisfaction.

Technical Mastery and Collaborative Relationships

Chabrol’s technical approach to filmmaking was characterized by meticulous preparation combined with flexibility during production. He was known for his extensive pre-production work, carefully planning shots and sequences while remaining open to spontaneous discoveries during filming. This balance between preparation and improvisation allowed him to maintain high production values while capturing the naturalistic performances that defined his work.

His long-term collaborations with key creative personnel contributed significantly to his consistent quality. Cinematographer Jean Rabier worked on many of Chabrol’s most important films, helping create the elegant visual style that became synonymous with the director’s work. Their partnership produced some of the most beautifully photographed films of the New Wave period, characterized by sophisticated use of natural light and carefully composed frames that served the psychological content of the stories.

Chabrol’s work with composer Pierre Jansen created memorable scores that enhanced his films’ psychological impact without overwhelming their subtle emotional rhythms. Their collaboration produced music that supported the psychological development of characters and situations while maintaining the restrained elegance that characterized Chabrol’s overall style.

The director’s relationship with his actors was particularly important to his success. He created an atmosphere on set that encouraged natural, unforced performances while maintaining the precision necessary for his carefully constructed narratives. Many actors returned to work with Chabrol multiple times, suggesting that his collaborative approach created satisfying creative relationships that benefited both director and performers.

Legacy and Influence on World Cinema

Claude Chabrol’s influence on world cinema extends far beyond his role in launching the French New Wave movement. His sophisticated approach to genre filmmaking demonstrated that popular entertainment could achieve artistic distinction without sacrificing commercial appeal. This lesson has been absorbed by filmmakers worldwide who seek to create personal cinema within established genre frameworks.

His psychological approach to suspense has influenced generations of directors who work in thriller and crime genres. Chabrol’s demonstration that tension could emerge from character relationships rather than external plot mechanisms has become a standard technique in contemporary cinema. Directors like Brian De Palma, Roman Polanski, and more recently, Denis Villeneuve and Jordan Peele, show clear influences from Chabrol’s psychological approach to suspense.

The director’s examination of class dynamics and social psychology has proven particularly influential in European cinema. Filmmakers like Michael Haneke, François Ozon, and Laurent Cantet have continued Chabrol’s tradition of using intimate stories to examine broader social issues. His influence can also be seen in the work of international directors who share his interest in bourgeois psychology and social observation.

Chabrol’s consistent productivity and maintaining of artistic standards throughout a long career provides a model for filmmakers seeking to balance personal vision with professional sustainability. His ability to work within commercial constraints while preserving his artistic integrity demonstrates that auteur filmmaking need not be confined to occasional projects or limited budgets.

Critical Reception and Academic Recognition

Throughout his career, Chabrol received consistent recognition from critics and academic observers who appreciated his sophisticated approach to popular filmmaking. While some critics initially dismissed his commercial period during the 1960s, subsequent evaluation has recognized these works as important steps in his artistic development that allowed him to refine his techniques and maintain his independence.

Academic study of Chabrol’s work has revealed the consistent thematic and stylistic development that characterizes his career. Scholars have particularly noted his contribution to the development of psychological realism in cinema and his sophisticated understanding of how visual style can support narrative content. His films are regularly included in university film curricula as examples of auteur filmmaking and New Wave innovation.

International recognition of Chabrol’s achievements has grown steadily since his death in 2010. Retrospective screenings and academic conferences have helped establish his reputation as one of the most important directors of his generation. His influence on contemporary filmmaking continues to be recognized by critics and filmmakers who appreciate his unique combination of artistic sophistication and popular appeal.

The director’s work has been preserved and celebrated by film archives worldwide, ensuring that future generations will have access to his complete filmography. The Cinémathèque Française, where Chabrol first developed his love of cinema, maintains extensive collections of his work and production materials that provide valuable resources for ongoing scholarship.

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of Chabrol’s Vision

Claude Chabrol’s death in 2010 marked the end of one of cinema’s most productive and consistent careers, but his influence continues to grow as new generations of filmmakers and audiences discover his work. His unique combination of psychological insight, technical mastery, and social observation created a body of work that remains relevant to contemporary concerns about class, morality, and human nature.

The director’s exploration of bourgeois psychology speaks to ongoing questions about the relationship between material success and personal fulfillment that remain central to modern life. His examination of how social pressures and individual desires create psychological conflicts provides insights that transcend the specific French contexts of his stories.

Chabrol’s technical innovations and genre sophistication continue to influence filmmakers seeking to create popular entertainment that achieves artistic distinction. His demonstration that auteur cinema could be both personal and commercially viable provides a model for contemporary directors working within industry constraints.

Perhaps most importantly, Chabrol’s consistent commitment to his artistic vision throughout a long career demonstrates the possibility of maintaining creative integrity while adapting to changing industry conditions. His example suggests that filmmakers need not choose between artistic achievement and professional success, but can find ways to pursue both goals simultaneously.

The French New Wave movement that Chabrol helped launch transformed world cinema by demonstrating that films could be both intellectually sophisticated and emotionally engaging. Chabrol’s career-long commitment to these principles ensures his lasting place in cinema history as both an innovator and a master craftsman whose work continues to reward careful attention and critical analysis.

In an era when film culture increasingly values spectacle over psychology and action over character development, Chabrol’s patient, intelligent approach to storytelling provides a valuable alternative model for cinematic excellence. His films remind us that the most profound dramas often emerge from the most ordinary circumstances, and that careful observation of human behavior can reveal truths about society and individual psychology that more obvious approaches might miss.

Claude Chabrol’s legacy extends beyond his individual achievements to encompass his demonstration that cinema can serve as both popular entertainment and serious art. His career stands as proof that filmmakers who combine technical skill with psychological insight and social observation can create works that satisfy immediate audiences while achieving lasting artistic significance. In this respect, he remains not only a master of the French New Wave but a model for filmmakers worldwide who seek to create cinema that is both meaningful and memorable.