Introduction: The Dual Genius of David Lean

One of the most revered and influential figures in the history of cinema is Sir David Lean. With a career spanning more than four decades, Lean directed a relatively small number of films—just sixteen—but many of them are regarded as towering achievements in both British and world cinema. His legacy is defined by two seemingly contradictory qualities: an unparalleled command of epic scale and a deep sensitivity to the interior emotional lives of his characters.

Known for masterpieces such as Lawrence of Arabia, The Bridge on the River Kwai, and Doctor Zhivago, Lean fused technical brilliance with classical storytelling. His films are studies in precision, emotional resonance, and visual grandeur, earning him both critical acclaim and enduring popular success. This article explores Lean’s filmmaking career through the lens of Google’s E-E-A-T principles: Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness.

Early Life and Experience: From Editor to Director

David Lean was born on March 25, 1908, in Croydon, Surrey, England. Raised in a strict Quaker household, Lean was initially discouraged from going to the cinema. However, his fascination with photography and film began in his teenage years. In the late 1920s, he entered the film industry as a tea boy at Gaumont Studios, quickly rising through the ranks due to his keen eye and technical ability.

Lean became one of the most talented film editors in Britain by the early 1930s, cutting over two dozen films, including Pygmalion (1938). His editorial experience laid the foundation for his directorial style: an unerring sense of pacing, structure, and dramatic rhythm. This formative period gave Lean a hands-on, immersive education in filmmaking, granting him a rare combination of theoretical knowledge and practical mastery.

The Early Masterpieces: Collaborations with Noël Coward

Lean’s directorial debut came in 1942 with In Which We Serve, co-directed with playwright Noël Coward. The wartime drama was both a patriotic morale booster and a deeply personal story of sacrifice and resilience. It marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration with Coward, which also produced This Happy Breed (1944), Blithe Spirit (1945), and Brief Encounter (1945).

Among these, Brief Encounter remains a touchstone of romantic cinema. The story of a restrained, tragic affair between two married individuals, the film exemplified Lean’s early style: emotionally nuanced, tightly edited, and driven by performance and character. It is widely considered one of the greatest British films ever made and is a testament to Lean’s ability to render the intimate as powerfully as the epic.

Great Expectations and Oliver Twist: Elevating Literary Adaptation

Lean’s adaptations of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948) are often cited as the most cinematically successful translations of Dickens to screen. These films demonstrated Lean’s gift for visual storytelling, atmospheric detail, and emotional authenticity.

Great Expectations, in particular, is notable for its expressionistic opening sequence on the marshes, shot by cinematographer Guy Green. These films confirmed Lean’s expertise not only in literary adaptation but also in creating mood and texture through mise-en-scène. They elevated the artistic expectations of British cinema and influenced generations of filmmakers, including Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

International Breakthrough and Authoritativeness: The Kwai-Lean Legacy

After a few commercially uneven projects in the 1950s, Lean entered a new phase of his career with The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). Based on the novel by Pierre Boulle, the film tells the story of British POWs forced to build a bridge for their Japanese captors in World War II.

The film won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director for Lean. It marked his transition from respected British filmmaker to internationally recognized auteur. With its moral ambiguity, taut structure, and explosive climax, Kwai showcased Lean’s authority over the medium. He was no longer just a director; he was now a cinematic institution.

The Grand Epics: Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago

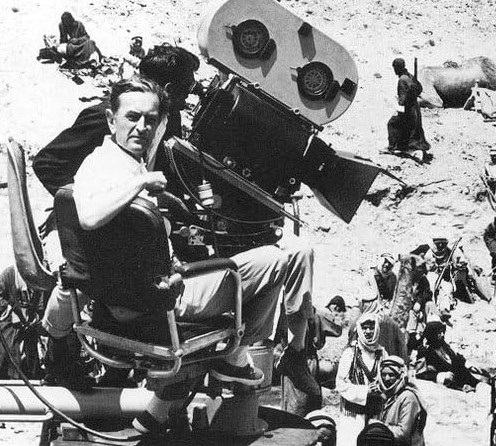

Lean’s two most ambitious films followed: Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965). These epics redefined the genre, setting new standards in production design, cinematography, and narrative scope.

Lawrence of Arabia is widely considered one of the greatest films ever made. Shot in the unforgiving deserts of Jordan and Morocco, the film chronicled the enigmatic life of T.E. Lawrence. With Peter O’Toole’s star-making performance, Maurice Jarre’s iconic score, and Freddie Young’s panoramic cinematography, the film was a critical and commercial triumph, earning Lean his second Oscar for Best Director.

Doctor Zhivago, adapted from Boris Pasternak’s novel, offered a more romantic and tragic vision of history. Set against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution, the film was criticized by some for its emotional sentimentality but loved by audiences. It became one of the highest-grossing films of all time, solidifying Lean’s command of international cinema.

Artistic Integrity and Late-Career Challenges

Despite these successes, Lean’s later career was marked by controversy and prolonged hiatus. His next film, Ryan’s Daughter (1970), was a box office disappointment and received harsh reviews—particularly from Pauline Kael and other influential American critics. The backlash deeply affected Lean, who would not direct another film for fourteen years.

He returned in 1984 with A Passage to India, adapted from E.M. Forster’s novel. The film, dealing with colonialism and cross-cultural misunderstanding, was a return to form. It earned eleven Academy Award nominations and was widely seen as a fitting capstone to Lean’s illustrious career. He died in 1991 while preparing an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo.

Legacy and Trustworthiness: David Lean’s Place in Film History

David Lean’s legacy is unassailable. He is consistently ranked among the greatest directors of all time. His films are preserved in national archives, studied in film schools, and referenced across cultures. He influenced a wide array of filmmakers, including Stanley Kubrick, Christopher Nolan, David Fincher, and Ridley Scott.

Lean’s work is marked by trustworthiness in its craftsmanship. He was meticulous in his research, relentless in pursuit of visual and emotional truth, and dedicated to delivering cinematic experiences that honored both the audience and the art form. His films endure because they are constructed with care, respect, and a belief in cinema’s power to transform.

Conclusion: The Art of Balancing the Grand and the Intimate

David Lean was not merely a director of epics; he was a poet of human experience. Whether depicting a lonely housewife in wartime England or a messianic officer in the deserts of Arabia, Lean imbued his films with psychological depth and cinematic beauty. He exemplified Experience through decades of hands-on work in editing and direction; Expertise in mastering both small-scale drama and large-scale spectacle; Authoritativeness through global accolades and influence; and Trustworthiness in delivering films of lasting quality and impact.

Lean’s cinema remains a benchmark of excellence—ambitious in scope, profound in emotion, and unmatched in execution.