In the sprawling landscape of mid-20th-century European cinema, certain films achieve iconic status not because they challenge the medium’s conventions or shatter artistic boundaries, but because they resonate culturally, emotionally, and historically in a way few others do. Ernst Marischka’s Sissi trilogy—Sissi (1955), Sissi – The Young Empress (1956), and Sissi – Fateful Years of an Empress (1957)—belongs to that rare class of cinematic works that, while often critiqued for their romanticized depictions and near-fairy-tale sensibilities, nevertheless occupy an enduring place in the canon of European film.

For many cinephiles, especially those enchanted by historical dramas outside the Hollywood mainstream, this trilogy is both a cultural artifact and a living myth—a vision of royalty that juxtaposes personal romance with the grandeur of imperial Austria. In this article, we explore this trilogy not merely as nostalgic entertainment, but as a cinematic phenomenon with implications for performance, identity, and post-war European imagination.

I. Origins and Context: Post-War Cinema and Heimatfilm Sensibilities

At its core, the Sissi trilogy is a product of its time—emerging in post-World War II Austria and Germany when audiences craved narratives that soothed, idealized, and healed. The “Heimatfilm” genre, which flourished in the 1950s, emphasized idyllic landscapes, moral clarity, family loyalty, and pastoral beauty. Within this context, the Sissi films distinguished themselves by blending romantic melodrama with historical pageantry.

Ernst Marischka (1893–1963), the trilogy’s writer, director, and (with Karl Ehrlich) producer, took a figure rooted in complex European history—Empress Elisabeth of Austria—and transformed her into a near-mythic heroine whose life unfolds in Technicolor splendor. Rather than grapple with the darker facets of Elisabeth’s life (which included personal tragedy, anorexia, depression, and political tension), Sissi elects a more rhapsodic narrative: a coming-of-age tale set against ornate court rituals, scenic lakes, and the youthful innocence of first love.

This aesthetic choice is crucial to understanding why the trilogy resonates: it is not striving for rigorous biography or historiographic fidelity. Instead, it crafts an aspirational vision of a young woman whose resilience and charm seem to transcend the strictures of her environment.

II. Sissi (1955): The Fairytale Begins

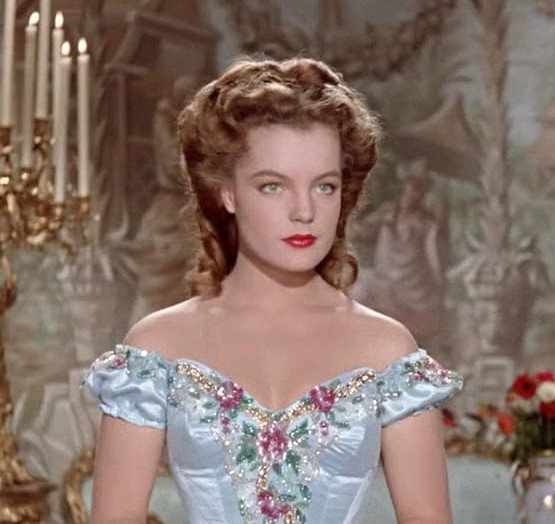

The first film in the trilogy introduces us to Princess Elisabeth of Bavaria—affectionately “Sissi”—a free-spirited sixteen-year-old whose spontaneous joy in life defies the rigid expectations of her aristocratic milieu. Romy Schneider’s performance, youthful and radiant, infuses Sissi with a blend of impetuosity and empathy that would become the emotional center of all three films.

From the outset, the film’s strengths lie not in historical precision but in its visual and emotional palette. Shot in vibrant Agfacolor with opulent costume design and framed by Austria’s natural beauty, Marischka sets out a world where romance feels inevitable and destiny seems poised to sweetly bend to youthful will. Schneider’s Sissi is both a historical figure and an archetype: the innocent heroine who wins her destiny as much through personal magnetism as through narrative necessity.

The film’s plot hinges on a classic tropic surprise. Intended to facilitate her sister’s alliance with Emperor Franz Joseph I, Sissi instead captivates him by happenstance. The film revels in the playful tension between societal expectations and personal desire, with courtly rituals rendered less as restrictive formalities and more as potential sites of poetic liberation.

III. Sissi – The Young Empress (1956): Marriage and Its Discontents

The second installment shifts from romantic courtship to the complexities of imperial life. Sissi, now empress, finds the palace environment stifling and at odds with her temperament. The mother-in-law, Archduchess Sophie, embodies the austere traditions that Sissi’s vivacity seems destined to upend.

Here, the film traces an arc familiar to audiences across eras: youthful idealism confronting the pragmatic realities of duty and expectation. Schneider’s Sissi continues to embody warmth and vivacity, but the film allows viewers to see how these traits adapt—or struggle—within the glittering cage of monarchy.

Critically, The Young Empress adds dimension to the trilogy by shifting from the whimsy of romance toward interpersonal negotiation. The dynamic between Sissi and Sophie serves not only as a narrative friction but as a commentary—intentional or otherwise—on women’s roles within power structures. Even in a narrative suffused with lyricism, we see glimpses of constraint and resistance.

IV. Sissi – Fateful Years of an Empress (1957): Complexity and Departure

The trilogy’s final chapter extends both narrative scope and emotional depth. In Sissi – Fateful Years of an Empress, the titular character seeks solace from courtly rigidities in the Hungarian countryside, where her affection for Hungarian culture and its people becomes a defining motif of her later years.

This film diverges from the simplicity of the first two by introducing more nuanced themes: the tension between personal desire and imperial duty, the emotional toll of chronic illness, and the strain of public expectation versus private fulfillment. While these films remain unabashedly romanticized, this third installment situates Sissi’s internal world against a broader geopolitical rhythm.

The narrative also depicts Sissi’s negotiation with her identity as both a sovereign and a woman shaped by emotional fidelity. Her resolve to balance love, duty, and self-determination foregrounds elements that subsequent historical dramas would later explore with harsher realism—but here they are presented with Marischka’s signature lyricism.

V. Performance and Legacy: Romy Schneider’s Enduring Sissi

Any discussion of the Sissi trilogy must emphasize Romy Schneider’s performance. Schneider, then in her late teens and early twenties, embodied the character with an ease that transcended the potentially cloying material. Her physical presence—wide-eyed, expressive, and luminous—made Sissi a cinematic icon across German-speaking Europe.

Yet this role, so defining, also became something Schneider wrestled with in her career. The youthful romanticism that made her portrayal beloved to audiences also risked typecasting her. Nonetheless, her work here is a masterclass in sustaining charm without tipping into mere coquettishness—a balance that provides the trilogy with its emotional core.

VI. Cultural Impact and Continued Relevance

The Sissi films have endured in ways that surprise even seasoned cinephiles. In Austria and Germany, they are perennial holiday viewing, embedded in cultural memory as nostalgic winter staples. Their continued broadcast and reissues testify to a narrative appeal that transcends minimalist realism, preferring emotional resonance and visual beauty.

That the films were later edited into a condensed feature (Forever My Love, released in North America in 1962) speaks to both their flexibility and their international appeal, even if this version lost much of the narrative texture of the original trilogy.

Moreover, the trilogy helped inspire later works engaging with the myth of Sisi, including musicals and miniseries that explore her life with varying degrees of historical scrutiny. While the Marischka films rarely appear on lists of global cinematic masterpieces, they remain pivotal for students of European period drama precisely because they reveal not just a story but a cultural longing for harmony, beauty, and grace after tumultuous decades.

VII. Conclusion: A Trilogy Worth Re-Evaluating

Ernst Marischka’s Sissi trilogy is more than a romantic costume piece—it is a cinematic window into post-war European aspirations, gendered narrative frameworks, and the interplay between historical mythmaking and personal identity. While its view of Empress Elisabeth may be idealized, its impact on cinema and audience imagination is undeniable.

For cinephiles seeking less conventional trilogies—works that defy arthouse minimalism yet carry emotional and cultural weight—the Sissi films reward repeated viewing. Their combination of performance, period detail, and narrative warmth ensures they remain not just artifacts of their decade, but enduring companions for anyone curious about how film shapes, sustains, and re-imagines historical memory.