Introduction

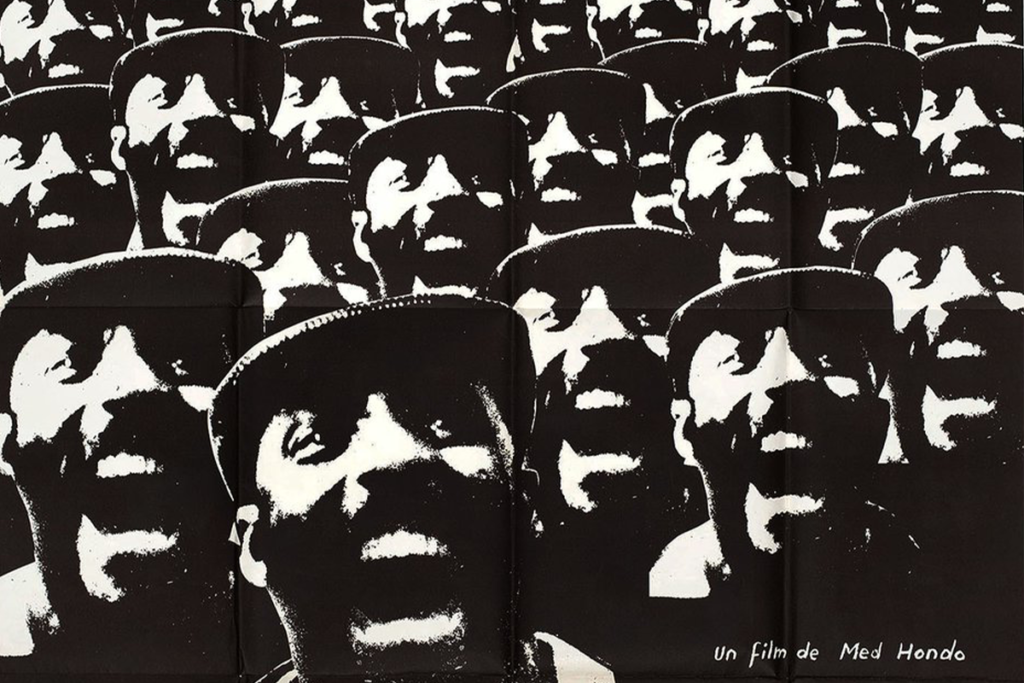

Third Cinema, a radical and politically charged film movement, emerged in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s as a response to colonial oppression, neocolonialism, and cultural imperialism. Unlike Hollywood’s First Cinema (commercial, entertainment-driven films) and European auteur-driven Second Cinema, Third Cinema sought to decolonize the screen, empower marginalized voices, and inspire revolutionary change.

This article explores the origins, key filmmakers, ideological foundations, and lasting impact of Third Cinema in Latin America. By analyzing seminal films and manifestos, we will uncover how this movement redefined cinema as a tool for liberation rather than passive consumption.

1. Historical and Political Context of Third Cinema

1.1. Postcolonial Struggles and Neocolonialism

Latin America’s history of colonization, dictatorship, and economic dependency created fertile ground for Third Cinema. After gaining independence in the 19th century, many Latin American countries remained economically dominated by foreign powers, particularly the United States. The mid-20th century saw U.S.-backed coups (e.g., Guatemala in 1954, Chile in 1973) and the rise of military dictatorships, fueling anti-imperialist resistance.

1.2. The Cuban Revolution’s Influence

The 1959 Cuban Revolution, led by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, became a symbol of anti-imperialist struggle. Cuban cinema, particularly the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), played a crucial role in shaping Third Cinema by producing films that aligned with revolutionary ideals.

1.3. The Rise of Leftist Movements

Across Latin America, Marxist and socialist movements gained momentum. Filmmakers, inspired by thinkers like Frantz Fanon, Paulo Freire, and Karl Marx, sought to create a cinema that would educate, mobilize, and challenge dominant power structures.

2. Defining Third Cinema: Manifestos and Theories

2.1. “Towards a Third Cinema” (1969) by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino

The most influential manifesto of the movement, Towards a Third Cinema, was written by Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino. They defined Third Cinema as:

- A cinema of liberation: Opposed to Hollywood’s escapism and European individualism.

- A weapon of revolution: Films should provoke action, not passive viewing.

- A participatory medium: Encouraging collective filmmaking and screenings in marginalized communities.

2.2. Glauber Rocha’s “Aesthetics of Hunger” (1965)

Brazilian filmmaker Glauber Rocha argued that Latin American cinema must embrace its “hunger” (hunger)—its poverty and oppression—rather than imitate European or Hollywood styles. He advocated for a raw, violent, and poetic cinema that exposed colonial brutality.

2.3. Julio García Espinosa’s “For an Imperfect Cinema” (1969)

The Cuban filmmaker rejected technical perfection, arguing that cinema should be accessible and politically urgent. Imperfect Cinema prioritized message over aesthetics, aligning with socialist ideals.

3. Key Filmmakers and Films of Third Cinema

3.1. Argentina: Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino

- Film: La Hora de los Hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces) (1968)

A four-hour documentary-essay divided into three parts, exposing Argentina’s neocolonial exploitation. It was secretly screened among activists to avoid censorship.

3.2. Brazil: Glauber Rocha

- Film: Terra em Transe (Entranced Earth) (1967)

A surreal, politically charged allegory about a poet caught in a revolutionary struggle, critiquing corruption and foreign intervention.

3.3. Cuba: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea

- Film: Memorias del Subdesarrollo (Memories of Underdevelopment) (1968)

A psychological drama about a bourgeois intellectual struggling to adapt post-revolution, questioning privilege and complicity.

3.4. Bolivia: Jorge Sanjinés

- Film: Yawar Mallku (Blood of the Condor) (1969)

Exposed the forced sterilization of Indigenous women by U.S. agencies, leading to real-world policy changes.

3.5. Chile: Patricio Guzmán

- Film: La Batalla de Chile (The Battle of Chile) (1975-1979)

A three-part documentary chronicling Salvador Allende’s socialist government and the 1973 U.S.-backed coup.

4. Aesthetic and Narrative Techniques

Third Cinema rejected conventional storytelling in favor of experimental techniques:

- Documentary hybridity: Blurring fiction and reality (La Hora de los Hornos).

- Non-linear narratives: Reflecting fragmented histories (Terra em Transe).

- Collective protagonists: Focusing on communities rather than individuals (Yawar Mallku).

- Direct audience address: Breaking the fourth wall to provoke discussion.

5. The Legacy of Third Cinema

5.1. Influence on Global Cinema

- Africa: Ousmane Sembène’s anti-colonial films.

- Asia: Kidlat Tahimik’s critiques of neocolonialism in the Philippines.

- Indigenous Cinema: Contemporary Indigenous filmmakers like Bolivian Alejandro Loayza Grisi (Utama, 2022) continue its spirit.

5.2. Modern Latin American Political Cinema

- Mexico: Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros (2000) critiques class disparity.

- Argentina: Lucrecia Martel’s Zama (2017) explores colonial alienation.

- Brazil: Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Bacurau (2019) revives Third Cinema’s militant aesthetics.

5.3. Digital Third Cinema

With YouTube and social media, activist filmmakers distribute works globally, continuing the movement’s ethos.

6. Criticisms and Challenges

- Didacticism: Some films prioritized message over artistry.

- Censorship and Repression: Many filmmakers faced exile or imprisonment.

- Commercial Pressures: Neoliberal economies made militant cinema harder to fund.

Conclusion

Third Cinema remains one of Latin America’s most vital cultural contributions, proving that film can be a weapon of resistance. By rejecting colonial narratives and empowering the oppressed, it redefined cinema’s role in society. Today, its legacy lives on in filmmakers who challenge injustice, proving that the struggle for decolonized storytelling continues.

References

- Solanas, F., & Getino, O. (1969). Towards a Third Cinema.

- Rocha, G. (1965). Aesthetics of Hunger.

- García Espinosa, J. (1969). For an Imperfect Cinema.

- Wayne, M. (2001). Political Film: The Dialectics of Third Cinema.