Introduction: Loving Cinema’s Quiet Architects

French cinema is often narrated through a familiar constellation of names: Renoir, Carné, Bresson, Godard, Truffaut, Melville. Their films anchor textbooks, retrospectives, and festival programs. Yet beyond these canonical figures exists another lineage — filmmakers who worked within the industry’s commercial core, shaped popular taste, discovered new tones and rhythms, collaborated with the greatest stars of their era, and yet remained curiously absent from the pantheon of auteurs. Georges Lautner belongs emphatically to this lineage.

For the cinephile who loves French cinema not only in its modernist ruptures but in its popular traditions, Lautner represents something essential: a director who mastered genres, invented tones, navigated between comedy and crime, and understood actors with rare intuition. He was neither a theoretician nor a manifesto writer. He did not court the Nouvelle Vague nor seek critical provocation. Instead, he built a body of work that reflected the evolving moods of postwar France — cynical, playful, disenchanted, violent, absurd — and offered some of the most memorable performances of Jean Gabin, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Alain Delon, and Lino Ventura.

To admire Lautner is, in a way, to admire the invisible infrastructure of French cinema: the artisans who kept studios alive, shaped stars’ careers, and created films that audiences returned to year after year. His cinema may not be experimental, but it is alive — rhythmical, ironic, stylish, and deeply rooted in French sensibility.

This is not an attempt to elevate Lautner artificially into the ranks of canonical auteurs. It is rather an effort to understand why his films matter, how his collaborations shaped the careers of legendary actors, and why filmmakers like him — prolific, adaptable, commercially successful yet critically overlooked — deserve renewed attention from those who care about cinema as both art and industry.

Origins: Inheriting a Cinema Legacy

Georges Lautner was born in 1926 into cinema almost by destiny. His father, Pierre Chenal, was himself a respected filmmaker of the 1930s and 1940s, associated with poetic realism and socially conscious drama. Growing up in this environment, Lautner absorbed cinema not as abstraction but as daily practice: sets, scripts, actors, producers, compromises.

Unlike many directors who arrived through criticism, theater, or cine-clubs, Lautner learned filmmaking from inside the machine. He worked as assistant director, observing how films were assembled under pressure, how stars behaved, how scripts changed during production, how budgets shaped aesthetics. This practical apprenticeship would mark his entire career. He was never seduced by theory. He trusted instinct, timing, and craft.

His early career unfolded in the 1950s, a transitional moment for French cinema. The old studio system was still alive, but new voices were emerging. The Nouvelle Vague would soon disrupt hierarchies and aesthetics. Lautner entered this world not as a rebel but as a professional — a director prepared to serve genres, stars, and audiences.

His first features already revealed a central trait: flexibility. Lautner could handle crime, comedy, melodrama, and hybrid forms with equal ease. This adaptability would later become both his strength and his curse. It allowed him to survive decades in a volatile industry, but it also prevented critics from attaching a single “signature” to his name.

A Cinema of Genre and Tone

To understand Lautner’s importance, one must first understand his relationship to genre. Unlike the auteurs of the Nouvelle Vague, who often dismantled genres, Lautner embraced them — but with irony, elasticity, and invention.

His films move freely between polar (French crime film), farce, thriller, and black comedy. Often, they combine these modes in unstable mixtures, producing tonal shifts that feel daring even today. Violence coexists with humor; grotesque caricature interrupts suspense; melancholy surfaces beneath bravado.

This tonal hybridity became one of Lautner’s signatures, even if critics rarely named it as such. He was fascinated by contradiction: tough men behaving foolishly, criminals speaking in poetry, aging gangsters confronting absurdity. In this sense, Lautner was closer in spirit to Italian commedia all’italiana or to the bitter comedies of Dino Risi than to the ascetic seriousness of Bresson or Melville.

What distinguishes Lautner is not visual radicalism but narrative rhythm and dialogue. His films breathe through timing: pauses, interruptions, reversals. He understood how to orchestrate scenes around actors’ physical presence and vocal cadence. This made him a director of performers above all.

Jean Gabin: The Aging Titan and the Bitter Smile

Perhaps no collaboration illustrates Lautner’s sensibility better than his work with Jean Gabin. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Gabin was no longer the tragic proletarian hero of poetic realism. He had become an aging titan — authoritative, weary, ironic.

Lautner understood that Gabin’s power now lay in his contradictions: strength mixed with resignation, dignity with sarcasm. Films such as Le Pacha (1968) transform Gabin into a mythic yet human figure — a gangster king confronting betrayal, generational change, and his own mortality.

In Le Pacha, Lautner balances crime drama with dry humor and political undertones. Gabin’s presence dominates the film, yet Lautner surrounds him with younger, more cynical figures, creating a portrait of a man out of time. The famous line “Quand on mettra les cons sur orbite, t’as pas fini de tourner” became part of French popular culture — a testament to Lautner’s ear for dialogue and Gabin’s mastery of delivery.

Rather than glorifying Gabin, Lautner humanized him. He allowed cracks in the monument. This approach would later define his collaborations with other stars, always seeking the fragile beneath the iconic.

Lino Ventura: The Ethics of Violence

If Gabin embodied the past, Lino Ventura embodied moral tension. Ventura’s screen persona combined physical power with introspective restraint. Lautner recognized in him a perfect vessel for ambiguous masculinity.

Their collaborations often revolve around men trapped between loyalty and survival, honor and betrayal. Lautner stages violence not as spectacle but as consequence. In films such as Les Tontons Flingueurs (1963) — his most famous work — Ventura plays against type, blending toughness with comedic timing.

Les Tontons Flingueurs occupies a unique place in French cinema. On the surface, it is a gangster comedy, filled with outrageous dialogue, caricatured criminals, and absurd situations. Yet beneath the farce lies a meditation on family, aging, and the exhaustion of outlaw mythology.

The film’s legendary kitchen scene — a drunken confrontation between aging gangsters — epitomizes Lautner’s art. Violence dissolves into comedy, masculinity into vulnerability. The dialogue, written by Michel Audiard, sparkles with wit, but Lautner’s direction gives it rhythm and space. The actors’ bodies, gestures, silences matter as much as the words.

The film’s enduring popularity in France is no accident. It captures a moment when gangster cinema could laugh at itself without losing its edge. Lautner achieved something rare: a cult classic that is also mainstream, literary yet popular, cynical yet affectionate.

Jean-Paul Belmondo: Energy, Irony, and Youth

Belmondo’s collaborations with Lautner belong to a different register. Where Gabin and Ventura embodied weight and experience, Belmondo brought speed, insolence, and athletic grace.

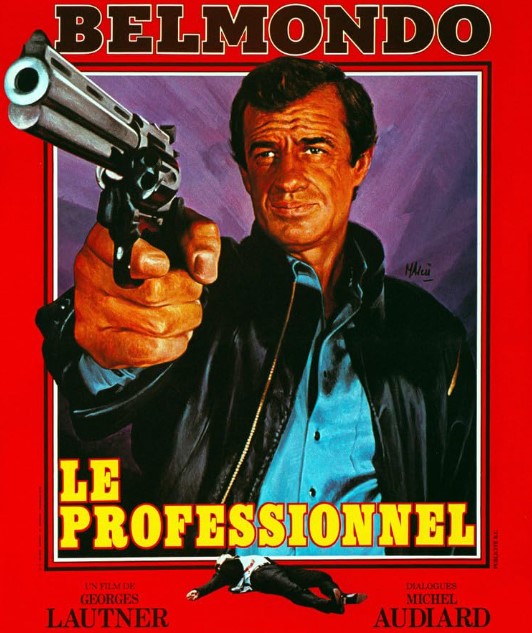

Lautner used Belmondo not simply as an action hero but as a vector of modernity. Films like Le Professionnel (1981) — though late in Lautner’s career — show his ability to adapt to new rhythms: international intrigue, Cold War paranoia, sleek choreography.

In Le Professionnel, Belmondo’s character is both spy and sacrificial figure, betrayed by institutions he once served. Lautner stages the film with classical clarity but infuses it with melancholy. Ennio Morricone’s iconic score, the tragic ending, and Belmondo’s weary charisma transform what could have been a conventional thriller into a meditation on loyalty and abandonment.

Here again, Lautner’s talent lies in tonal balance. He allows action to coexist with fatalism, spectacle with introspection. Belmondo is heroic, but the heroism feels exhausted, almost obsolete.

Alain Delon: Cool, Cruel, and Enigmatic

Alain Delon, perhaps the most enigmatic of French stars, required a director capable of harnessing his icy charisma without suffocating it. Lautner proved to be one of those directors.

Their collaborations reveal Delon not only as icon but as actor of moral opacity. Lautner places Delon in narratives where beauty becomes dangerous, where silence speaks louder than action. Unlike Melville, who turned Delon into an abstract symbol, Lautner keeps him anchored in psychological and social contexts.

In Lautner’s universe, Delon is never entirely mythic. He belongs to a world of corrupt institutions, criminal networks, and fragile alliances. The director’s pragmatic realism tempers the star’s perfection, introducing cracks in the mirror.

This balance between glamour and decay is one of Lautner’s most subtle achievements. He understood that French stardom was itself a genre — one that needed to be staged, questioned, and sometimes mocked.

Dialogue as Architecture: The Audiard Partnership

No discussion of Lautner can avoid Michel Audiard. Their collaboration stands among the most fruitful director–screenwriter partnerships in French popular cinema.

Audiard’s dialogue is legendary: sharp, vulgar, poetic, philosophical, streetwise. But dialogue alone does not create cinema. What Lautner brought was architectural intelligence. He knew where to place lines, when to interrupt them, how to let actors breathe between insults and aphorisms.

In Les Tontons Flingueurs, Le Pacha, and several other films, the dialogue becomes musical. Insults become arias, metaphors become weapons. Yet Lautner never lets language dominate image. He frames conversations dynamically, choreographs bodies in space, uses props, glances, and silences to enrich meaning.

This synergy explains why many Audiard lines are inseparable from Lautner’s staging. Remove the rhythm, the blocking, the facial reactions, and the words would lose half their meaning

Conclusion: Why Lautner Matters

To write about Georges Lautner today is not to correct history but to enrich it. He was not a neglected genius in the romantic sense. He was something rarer: a director who understood cinema as living practice, who respected audiences without flattering them, who shaped stars without imprisoning them, who balanced laughter and despair with instinctive grace.

His place may remain in the shadows, but it is a luminous shadow — one that reveals the complexity of French cinema beyond its monuments. For those who love cinema not only as theory but as experience, Lautner is not a footnote. He is a companion.

And perhaps that is the highest tribute one can offer.