Introduction

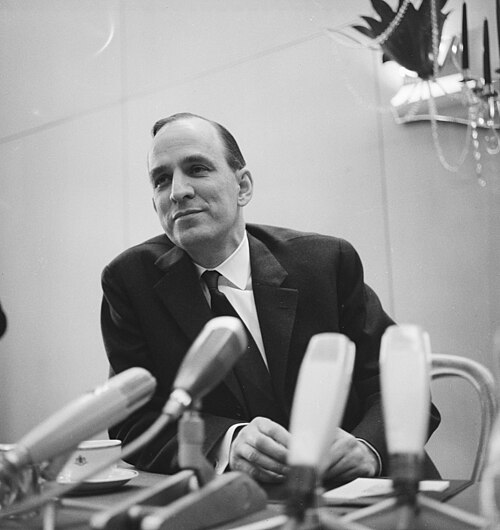

Ernst Ingmar Bergman (1918–2007) stands as one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema. A master of psychological depth, existential inquiry, and visual poetry, Bergman crafted films that explored the human condition with unparalleled intensity. Over a career spanning more than six decades, he directed over 60 films and 170 theatrical productions, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with audiences and filmmakers alike.

Bergman’s films are characterized by their stark emotional honesty, meticulous composition, and profound philosophical questions about faith, mortality, love, and identity. His influence extends beyond the realm of art-house cinema, shaping the work of directors such as Woody Allen, Andrei Tarkovsky, Lars von Trier, and Martin Scorsese. This article delves into Bergman’s life, his most significant films, his distinctive directorial style, and his lasting impact on world cinema.

Early Life and Influences

Born on July 14, 1918, in Uppsala, Sweden, Ingmar Bergman was raised in a strict Lutheran household. His father, Erik Bergman, was a conservative pastor, while his mother, Karin Åkerblom, came from an upper-middle-class family. The tension between religious austerity and emotional repression in his upbringing would later become a recurring theme in his films.

Bergman’s fascination with storytelling began in childhood. He received a film projector as a gift at the age of nine, which ignited his passion for cinema. By his teenage years, he was staging amateur theatrical productions and writing plays. He studied literature and art history at Stockholm University but soon abandoned formal education to pursue theater and film.

His early career was marked by work as a scriptwriter and assistant director at Svensk Filmindustri (SF), Sweden’s leading film studio. His first directorial effort, Crisis (1946), was a melodrama influenced by the style of 1940s Swedish cinema. Though not a critical success, it marked the beginning of a career that would redefine cinematic storytelling.

Breakthrough and Major Works

1950s: Establishing a Unique Voice

Bergman’s early films were largely conventional, but by the mid-1950s, he began developing his signature style. Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), a sophisticated romantic comedy, won international acclaim and earned him a Cannes Film Festival award. This success allowed him greater creative freedom, leading to The Seventh Seal (1957), the film that would cement his reputation as a visionary.

The Seventh Seal (1957)

Set during the Black Death, The Seventh Seal follows a disillusioned knight, Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), who plays a chess game with Death (Bengt Ekerot) while questioning the silence of God. The film’s iconic imagery—the knight on the beach, the dance of death—became emblematic of Bergman’s existential themes. It remains one of the most analyzed films in cinema history, blending medieval allegory with post-war disillusionment.

Wild Strawberries (1957)

Released the same year, Wild Strawberries is a poignant meditation on aging and regret. Professor Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström) embarks on a road trip that becomes a journey into his past, confronting lost love and personal failures. The film’s dream sequences and nonlinear narrative influenced later filmmakers like Federico Fellini and David Lynch.

1960s: Psychological and Spiritual Explorations

The 1960s marked Bergman’s most prolific and critically acclaimed period. He explored themes of faith, mental illness, and human relationships with increasing intensity.

The Virgin Spring (1960)

A brutal medieval tale of revenge and divine justice, The Virgin Spring won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Its stark depiction of violence and moral ambiguity foreshadowed the work of directors like Lars von Trier.

Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), and The Silence (1963)

These three films form Bergman’s “Faith Trilogy,” each examining the absence of God and the fragility of human connection. Through a Glass Darkly depicts a woman’s descent into schizophrenia, Winter Light portrays a crisis of faith in a small-town pastor, and The Silence explores alienation through two sisters in a war-torn country. These films solidified Bergman’s reputation as a filmmaker unafraid to confront despair.

Persona (1966)

Often regarded as Bergman’s masterpiece, Persona is a psychological tour de force. The film follows an actress (Liv Ullmann) who suddenly stops speaking and her nurse (Bibi Andersson), whose identities begin to merge. With its experimental structure, haunting imagery, and themes of identity and performance, Persona pushed the boundaries of narrative cinema and remains a landmark of modernist filmmaking.

1970s: Intimate Dramas and Exile

Bergman’s personal life was tumultuous in the 1970s. A tax evasion scandal in 1976 led to a self-imposed exile in Germany, where he directed The Serpent’s Egg (1977), a dark thriller set in Weimar Germany. Despite this setback, he produced some of his most emotionally raw works.

Cries and Whispers (1972)

A harrowing depiction of death and sisterly conflict, Cries and Whispers uses a palette of red and white to evoke pain and purity. The film’s unflinching portrayal of suffering earned it an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture.

Scenes from a Marriage (1973)

Originally a TV miniseries, Scenes from a Marriage dissects the disintegration of a relationship with brutal honesty. Its realistic dialogue and emotional depth influenced countless domestic dramas, including Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy.

Autumn Sonata (1978)

Starring Ingrid Bergman (no relation) and Liv Ullmann, this film explores the fraught relationship between a celebrated pianist and her neglected daughter. The confrontational performances and Bergman’s precise direction make it one of his most powerful chamber dramas.

1980s and Beyond: Final Masterpieces

Bergman announced his retirement from filmmaking after Fanny and Alexander (1982), though he continued working in theater and television.

Fanny and Alexander (1982)

A semi-autobiographical epic, Fanny and Alexander blends magical realism with family drama. The film’s lush visuals and Dickensian narrative earned it four Academy Awards, including Best Foreign Language Film. Bergman intended it as a summation of his career, weaving together themes of childhood, art, and the supernatural.

In his later years, he directed television films like Saraband (2003), a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage, before passing away on July 30, 2007, at the age of 89.

Directing Style and Techniques

Bergman’s filmmaking was marked by several distinctive elements:

1. Psychological Depth and Existential Themes

Bergman’s films often grapple with existential questions—Does God exist? What is the meaning of suffering? His characters are introspective, frequently artists or intellectuals in crisis.

2. Minimalist Aesthetics

He favored austere compositions, especially in his black-and-white films. Long close-ups, sparse landscapes, and confined spaces (like the island in Persona) heighten the emotional intensity.

3. Collaboration with Key Actors and Crew

Bergman had a repertory company of actors, including Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, Bibi Andersson, and Erland Josephson. His longtime cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, developed a naturalistic lighting style that became a hallmark of their work.

4. Use of Dreams and Memory

Films like Wild Strawberries and Persona employ dream sequences to explore subconscious fears and desires, influencing later surrealist filmmakers.

5. Chamber Drama Approach

Many of his films (Cries and Whispers, Autumn Sonata) are intimate, dialogue-driven dramas with small casts, resembling theatrical plays.

Legacy and Influence

Bergman’s impact on cinema is immeasurable. His introspective approach paved the way for European art cinema and inspired directors across genres:

- Woody Allen frequently references Bergman, particularly in Interiors (1978) and Another Woman (1988).

- Andrei Tarkovsky admired Bergman’s spiritual depth, evident in The Mirror (1975).

- Lars von Trier and the Dogme 95 movement drew from Bergman’s raw emotional honesty.

- Martin Scorsese has cited The Virgin Spring and Persona as major influences on his work.

Film festivals, retrospectives, and academic studies continue to celebrate Bergman’s oeuvre. The Ingmar Bergman Foundation preserves his archives, ensuring that future generations engage with his work.

Conclusion

Ingmar Bergman was more than a filmmaker—he was a philosopher of the human soul. His films, with their unflinching gaze at life’s darkest and most luminous moments, remain timeless. Whether through the chess game with Death in The Seventh Seal or the merging identities in Persona, Bergman’s work challenges viewers to confront their own existential dilemmas.

His legacy endures not only in the canon of great cinema but in the very way we understand storytelling, psychology, and visual art. As Bergman himself once said:

“No form of art goes beyond ordinary consciousness as film does, straight to our emotions, deep into the twilight room of the soul.”

And in that twilight room, Bergman’s voice still echoes, profound and unshaken.