Among cinema’s most transformative forces, Italian Neorealism fundamentally reshaped not only the trajectory of Italian filmmaking but revolutionized the entire global cinematic landscape as one of the medium’s most influential and enduring movements. Emerging from the ashes of World War II, this revolutionary approach to storytelling rejected the artificiality of studio productions in favor of authentic portrayals of everyday life, social struggle, and human dignity. More than a mere aesthetic choice, Neorealism represented a moral and political commitment to truth-telling that would inspire filmmakers across the globe for decades to come.

The Genesis of a Movement

The roots of Italian Neorealism can be traced to the complex social and political circumstances of 1940s Italy. Following the fall of Mussolini’s fascist regime in 1943 and the subsequent German occupation, Italy found itself devastated by war, occupation, and civil conflict. Cities lay in ruins, the economy was shattered, and society was fractured along political and class lines. Traditional institutions, including the film industry, were in chaos.

During the fascist period, Italian cinema had been dominated by the so-called “white telephone” films—escapist entertainments featuring wealthy characters in luxurious settings, often imported from Hollywood or produced in imitation of American and German models. These films, while sometimes technically proficient, bore little resemblance to the reality of Italian life and served primarily as propaganda tools for the regime. The fall of fascism created both a practical necessity and an artistic opportunity for a new kind of cinema.

The theoretical foundations of Neorealism had been laid even before the war’s end. Film critic and theorist Cesare Zavattini, who would become the movement’s primary intellectual voice, had been advocating for a cinema that would abandon artificial plots and theatrical conventions in favor of direct observation of reality. As early as 1942, he wrote about the need for films that would “follow a man with a camera” and capture the poetry of everyday existence.

The movement’s first recognizable work emerged in 1943 with Luchino Visconti’s “Ossessione,” an unauthorized adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel “The Postman Always Rings Twice.” While not yet fully embodying all the characteristics that would define mature Neorealism, the film’s use of real locations, natural lighting, and focus on working-class characters marked a decisive break from the conventions of fascist-era cinema.

Defining Characteristics and Aesthetic Principles

Italian Neorealism was never a formal movement with manifestos or rigid rules, but rather a shared sensibility that emerged organically from the specific conditions of post-war Italy. Nevertheless, certain characteristics became associated with Neorealist films, though individual directors interpreted these elements with considerable freedom.

Perhaps most importantly, Neorealist films rejected the artificial environments of film studios in favor of real locations. Directors shot in the streets, in actual homes, in bombed-out buildings, and in the countryside. This choice was initially driven by practical considerations—many studios had been destroyed or damaged during the war—but it became a fundamental aesthetic principle. The use of real locations lent an immediacy and authenticity to the films that studio sets could never achieve.

The movement also embraced the use of non-professional actors, often casting people who had actually lived through the experiences depicted on screen. This approach served multiple purposes: it created more naturalistic performances, it was economically necessary given the limited budgets available, and it reinforced the films’ connection to authentic social reality. Professional actors, when used, were expected to adopt a more naturalistic style that avoided theatrical gestures and mannered delivery.

Neorealist cinematography typically employed natural lighting whenever possible, avoiding the elaborate lighting schemes of traditional studio productions. This approach, combined with the use of real locations, created a documentary-like visual style that suggested objective observation rather than artistic manipulation. Camera movements were generally functional rather than expressive, serving to follow the action rather than to create visual effects.

The narrative structure of Neorealist films often departed from classical Hollywood conventions. Rather than following tightly constructed plots with clear beginnings, middles, and ends, many Neorealist works adopted an episodic structure that reflected the randomness and uncertainty of real life. Stories might end ambiguously, without clear resolution, mirroring the open-ended nature of actual human experience.

Thematically, Neorealist films focused on the struggles of ordinary people, particularly the working class and the poor. Common subjects included unemployment, poverty, family dissolution, and social injustice. The films often depicted characters caught between traditional values and the dislocations of modern life, struggling to maintain dignity and human connection in difficult circumstances.

The Master Filmmakers

Three directors are universally recognized as the founding fathers of Italian Neorealism: Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Luchino Visconti. Each brought a distinctive approach to the movement while sharing its fundamental commitment to authentic representation.

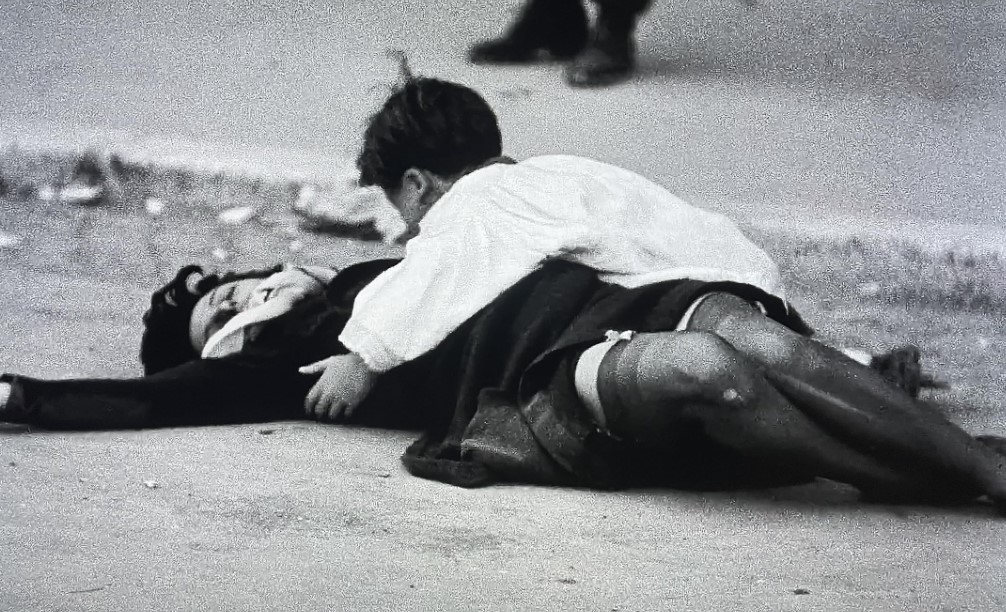

Roberto Rossellini emerged as Neorealism’s most prominent voice with his “War Trilogy”: “Rome, Open City” (1945), “Paisan” (1946), and “Germany Year Zero” (1948). These films, particularly “Rome, Open City,” established many of the movement’s key characteristics. Shot on location in Rome with a mixture of professional and non-professional actors, the film depicted the Italian resistance to Nazi occupation with unprecedented realism and emotional power. Rossellini’s approach was characterized by a sense of immediacy and spontaneity, as if the camera were simply recording events as they unfolded.

“Rome, Open City” was revolutionary not only in its style but in its content. The film presented a complex view of the resistance that avoided simple heroism, showing both the courage and the vulnerability of ordinary people under extreme circumstances. The famous torture scene, in which the priest Don Pietro is interrogated by the Gestapo, demonstrated Rossellini’s ability to combine documentary-like observation with intense dramatic power.

Vittorio De Sica, working closely with screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, created some of Neorealism’s most celebrated and influential works. “Shoeshine” (1946) told the story of two Roman boys whose friendship is destroyed by poverty and social injustice. “Bicycle Thieves” (1948) followed a working-class father whose bicycle—essential to his job—is stolen, forcing him into a desperate search through the streets of Rome. “Umberto D.” (1952) portrayed an elderly pensioner facing eviction and contemplating suicide.

De Sica’s films were characterized by their deep humanism and their focus on social injustice. Unlike some other Neorealist directors, De Sica and Zavattini were explicitly committed to using cinema as a tool for social criticism and reform. Their films demonstrated how individual suffering was connected to broader social problems, arguing implicitly for political change.

Luchino Visconti brought a more complex and sometimes contradictory approach to Neorealism. His “La Terra Trema” (1948), based on Giovanni Verga’s novel “I Malavoglia,” depicted the struggles of Sicilian fishermen against economic exploitation. Shot entirely on location in Sicily using local fishermen as actors, the film embodied many Neorealist principles while also displaying Visconti’s distinctive visual sophistication and political consciousness.

Visconti’s aristocratic background and Marxist politics created a unique perspective within Neorealism. His films combined detailed social observation with a more overtly political analysis than those of his contemporaries. “La Terra Trema” was conceived as the first part of a trilogy examining the exploitation of fishermen, miners, and peasants, though the other parts were never completed.

Beyond the Founding Fathers

While Rossellini, De Sica, and Visconti established Neorealism’s foundations, numerous other directors contributed to the movement’s development and evolution. Giuseppe De Santis created powerful films about rural life and social struggle, including “Bitter Rice” (1949), which combined Neorealist techniques with elements of melodrama and spectacle. Federico Fellini began his career as a Neorealist, co-writing “Rome, Open City” and directing “Variety Lights” (1950) before developing his own distinctive style.

Pietro Germi explored themes of social justice and legal reform in films like “In the Name of the Law” (1949) and “The Path of Hope” (1950). These works demonstrated how Neorealist techniques could be applied to different genres and subject matters while maintaining the movement’s fundamental commitment to social realism.

Michelangelo Antonioni, though often associated with later developments in Italian cinema, also began within the Neorealist tradition. His early films, including “Chronicle of a Love Affair” (1950) and “The Vanquished” (1953), applied Neorealist observation techniques to the psychological exploration of middle-class characters.

The International Impact

Italian Neorealism’s influence extended far beyond Italy’s borders, inspiring filmmakers around the world and contributing to the development of various national cinema movements. The movement’s emphasis on authentic locations, non-professional actors, and social realism provided a powerful alternative to the dominant Hollywood model.

In France, the New Wave directors of the 1950s and 1960s explicitly acknowledged their debt to Neorealism. Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and others adopted Neorealist techniques while developing their own distinctive approaches to filmmaking. The French New Wave’s emphasis on location shooting, natural lighting, and personal expression can be traced directly to Neorealist innovations.

The influence of Neorealism was particularly strong in developing nations, where filmmakers found in the Italian model a way to create authentic national cinemas without the resources required for studio-based production. Directors like Satyajit Ray in India, Glauber Rocha in Brazil, and Youssef Chahine in Egypt all acknowledged their debt to Neorealist pioneers.

In the United States, Neorealism influenced the development of independent filmmaking and contributed to the emergence of more socially conscious Hollywood films in the 1960s and 1970s. Directors like Sidney Lumet, John Cassavetes, and later Martin Scorsese incorporated Neorealist techniques into their work, creating a more authentic American cinema.

The Decline and Transformation

By the mid-1950s, Italian Neorealism as a coherent movement had begun to decline. Several factors contributed to this transformation. Economic recovery in Italy reduced the immediate social urgency that had driven the movement’s creation. The film industry’s increasing commercialization made it more difficult to finance and distribute the kind of small-scale, socially conscious films that had characterized classic Neorealism.

Additionally, the movement’s major directors began to evolve in different directions. Rossellini moved toward more abstract, philosophical filmmaking with works like “Voyage to Italy” (1954). De Sica continued to make socially conscious films but increasingly incorporated elements of comedy and melodrama. Visconti developed a more operatic style that would eventually lead to elaborate historical epics.

The rise of television also changed the context for Neorealist techniques. The documentary-like style that had been revolutionary in cinema became commonplace on television, reducing its impact and novelty. Young filmmakers began to explore other approaches to authentic representation, leading to the development of new movements and styles.

However, the decline of Neorealism as a movement did not represent a complete break with its principles. Many of its techniques and concerns were absorbed into mainstream filmmaking, becoming part of the general vocabulary of cinema. The movement’s emphasis on social realism continued to influence Italian directors like the Taviani brothers, Ermanno Olmi, and Ken Loach, who adapted Neorealist principles to contemporary concerns.

Theoretical Foundations and Critical Reception

The theoretical foundation of Italian Neorealism was most thoroughly articulated by Cesare Zavattini, whose writings and interviews provided the movement’s intellectual framework. Zavattini argued that cinema should abandon artificial plots and theatrical conventions in favor of direct observation of reality. He advocated for what he called “cinema verité”—a cinema that would capture the poetry and drama inherent in everyday life.

According to Zavattini, the ideal Neorealist film would follow a man for ninety minutes without anything “happening” in the traditional dramatic sense. The camera would simply observe, and the audience would discover the profound significance of ordinary experience. This approach required a fundamental shift in how both filmmakers and audiences understood cinema’s purpose and potential.

Zavattini’s theoretical writings emphasized the moral dimension of Neorealist practice. He argued that the movement’s techniques were not merely aesthetic choices but represented a commitment to truth-telling and social justice. By showing the reality of Italian life, particularly the struggles of the poor and working class, Neorealist films could contribute to social understanding and political change.

The critical reception of Neorealist films was complex and often divided along political lines. Left-wing critics generally celebrated the movement’s social commitment and authentic representation of working-class life. Conservative critics, particularly in Italy, sometimes criticized the films for presenting an overly negative view of Italian society that might damage the country’s international reputation.

International critics were generally more positive, recognizing the movement’s aesthetic innovations and humanitarian values. The success of films like “Bicycle Thieves” and “Rome, Open City” at international film festivals helped establish Neorealism’s reputation as a major artistic movement.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The legacy of Italian Neorealism extends far beyond its immediate historical period. The movement’s techniques and principles have been absorbed into the general vocabulary of cinema, influencing everything from documentary filmmaking to contemporary social realism. The use of real locations, non-professional actors, and natural lighting has become commonplace in both art house and commercial cinema.

More importantly, Neorealism’s moral commitment to authentic representation and social justice continues to inspire filmmakers around the world. Contemporary directors like Ken Loach, the Dardenne brothers, and Cristian Mungiu have explicitly acknowledged their debt to Neorealist principles while adapting them to contemporary concerns.

The movement’s influence can also be seen in the development of digital filmmaking technologies that have made location shooting and naturalistic production techniques more accessible to independent filmmakers. The democratization of filmmaking technology has, in some ways, fulfilled Zavattini’s vision of a cinema that could capture the poetry of everyday life without the mediation of elaborate studio apparatus.

In contemporary film criticism and theory, Neorealism is recognized as a crucial moment in cinema’s development, representing a successful challenge to the dominance of Hollywood narrative conventions. The movement demonstrated that cinema could be both artistically sophisticated and socially relevant, providing a model for engaged filmmaking that remains influential today.

Conclusion

Italian Neorealism represents one of cinema’s most significant and enduring contributions to the art form. Born from the specific circumstances of post-war Italy, the movement transcended its origins to become a universal model for authentic, socially conscious filmmaking. Its emphasis on real locations, non-professional actors, and natural lighting created a new aesthetic that challenged the dominance of studio-based production while its commitment to depicting the struggles of ordinary people provided a moral framework for engaged cinema.

The movement’s influence extends far beyond its immediate historical period, inspiring filmmakers around the world and contributing to the development of various national cinema movements. Its techniques have been absorbed into mainstream filmmaking, while its principles continue to guide directors committed to authentic representation and social justice.

Perhaps most importantly, Italian Neorealism demonstrated that cinema could be both artistically sophisticated and socially relevant, providing a model for filmmaking that remains as relevant today as it was in the 1940s. In an era of increasing social inequality and political fragmentation, the movement’s commitment to human dignity and authentic representation offers both inspiration and practical guidance for contemporary filmmakers.

The legacy of Italian Neorealism reminds us that cinema’s greatest power lies not in its ability to create spectacular illusions but in its capacity to reveal the poetry and drama inherent in everyday life. By choosing to look closely at the struggles and triumphs of ordinary people, the Neorealist directors created a cinema that was both revolutionary in its techniques and timeless in its humanity. Their work continues to inspire and challenge filmmakers to create a cinema worthy of the complexity and dignity of human experience.

Related topics:

White Telephone Films: Fascist-Era Italian Cinema and Its Glamorous Escapism – deepkino.com

Giallo Cinema: The Art of Stylish Violence and Psychological Horror in Italian Film – deepkino.com

Michelangelo Antonioni: Alienation, Modernity, and the Language of Cinema – deepkino.com

Pingback: The Trilogy of Incommunicability: Antonioni’s Quiet Earthquakes - deepkino.com

Pingback: Michelangelo Antonioni: Alienation, Modernity, and the Language of Cinema - deepkino.com

Pingback: Walking Through the Rubble: Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy and the Moral Birth of Neorealism - deepkino.com