There is a moment—often late, often unexpected—when a cinephile realizes that cinema is not always something to be watched. Sometimes it must be listened to. Sometimes it must be entered, like a ritual, without the protective armor of plot, psychology, or conventional narrative logic. My encounter with Carlos Saura’s Flamenco Trilogy—Blood Wedding (1981), Carmen (1983), and El Amor Brujo (1986)—was such a moment.

These films do not announce themselves as revolutions. They do not shout their intentions. Instead, they invite, patiently and insistently, a recalibration of how one perceives cinema itself. Saura does not merely film dance. He dismantles cinema’s illusionism and rebuilds it as a space where music, movement, memory, and identity coexist without hierarchy.

To approach the Flamenco Trilogy is to approach cinema at its most stripped and concentrated—where form becomes content, and performance becomes narrative. These are not adaptations in the traditional sense, nor are they musicals, nor are they documentaries. They exist somewhere between rehearsal and performance, between myth and embodiment, between Spain’s cultural memory and modernist abstraction.

For a cinephile already fluent in stylized cinema—Bergman’s theatrical spaces, Godard’s self-awareness, Fellini’s ritualized bodies—Saura’s trilogy offers something both familiar and startlingly new: cinema as corporeal thought.

Carlos Saura Before Flamenco: Memory, Repression, and the Body

To understand why the Flamenco Trilogy feels so radical, one must first understand the filmmaker behind it. Carlos Saura emerged as one of the most important Spanish directors during the final decades of Franco’s dictatorship, a period in which direct political critique was dangerous, if not impossible. Saura’s early films—The Hunt, Peppermint Frappé, Cría Cuervos—developed a language of metaphor, memory, and psychological displacement to address trauma, repression, and identity.

Even before flamenco entered his cinema, Saura was obsessed with the body as a carrier of history. His characters often move through spaces haunted by the past, performing rituals they do not fully understand. Time collapses. Childhood memories intrude into adult consciousness. The present is never autonomous.

What the Flamenco Trilogy does is radicalize this impulse. Saura abandons psychological realism almost entirely and transfers meaning directly into movement, rhythm, and gesture. Where his earlier films used symbolism to represent repression, the flamenco films allow repression, desire, and conflict to be embodied.

This shift marks a turning point not only in Saura’s career but in European art cinema more broadly. He stops using cinema to explain inner states and starts using cinema to host them.

Flamenco as Cultural Memory

Flamenco is not merely a dance form. It is an archive of suffering, resistance, love, jealousy, exile, and survival. Born from the cultural intersections of Andalusian, Romani, Moorish, Jewish, and working-class Spanish traditions, flamenco carries within it centuries of unrecorded history.

Saura understands this intuitively. He does not treat flamenco as folklore to be preserved or as spectacle to be consumed. He treats it as a language—one capable of expressing what spoken language cannot.

In the Flamenco Trilogy, flamenco becomes a narrative system. Feet replace exposition. Guitar replaces dialogue. Breath replaces montage.

This is not decorative. It is structural.

Blood Wedding (1981): Tragedy Without Psychology

The first film of the trilogy, Blood Wedding, announces Saura’s intentions with remarkable clarity. Based on Federico García Lorca’s play, the film discards almost everything traditionally associated with adaptation. There are no realistic sets, no illusion of period authenticity, no psychological backstory offered through dialogue.

Instead, Saura stages the film as a rehearsal that gradually becomes a performance. Dancers warm up. Costumes are donned in front of the camera. Musicians tune their instruments. The artificiality is not hidden—it is foregrounded.

This self-consciousness is crucial. Saura refuses to pretend that cinema can recreate reality. Instead, he allows cinema to become a space of transformation.

The narrative—an inevitable love triangle ending in death—is not acted so much as enacted. The dancers do not portray characters with interior monologues; they embody forces: desire, duty, honor, inevitability.

What strikes a cinephile encountering Blood Wedding is how little is lost by the absence of conventional drama—and how much is gained. The emotions are not diluted by explanation. They are intensified by abstraction.

The climactic duel, danced rather than staged, does not attempt to convince us of its realism. It convinces us of its truth. This is tragedy not as psychology but as fate.

In Blood Wedding, Saura establishes the trilogy’s foundational principle: cinema does not need realism to be real.

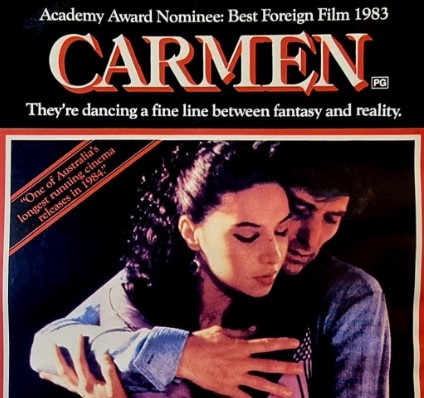

Carmen (1983): Cinema Becomes a Mirror

If Blood Wedding is austere and ritualistic, Carmen is playful, reflexive, and dangerously seductive. It is also the most overtly cinematic film in the trilogy, and perhaps the most intellectually thrilling.

Here, Saura introduces a layered narrative: a flamenco troupe rehearses a dance adaptation of Carmen, and gradually, the relationships between the dancers begin to mirror the story they are performing. Fiction bleeds into reality. Performance becomes destiny.

This structure is not a gimmick. It allows Saura to explore one of cinema’s deepest questions: where does representation end, and where does lived experience begin?

Carmen is a film about desire as performance and performance as desire. The titular figure is not simply a character; she is an archetype that consumes those who attempt to possess her. The dancer playing Carmen becomes Carmen—not because the script demands it, but because the myth demands embodiment.

For a cinephile attuned to modernist cinema, Carmen resonates with Pirandello, with Godard’s meta-narratives, with Fassbinder’s use of theatricality to expose emotional power structures. Yet Saura’s approach is distinct. He does not intellectualize reflexivity. He dances it.

The camera moves with the dancers, not to embellish them, but to submit to their rhythm. Editing follows breath and footwork rather than narrative beats. Music dictates time.

Carmen is cinema discovering that it can think through the body.

El Amor Brujo (1986): Cinema as Possession

The final film of the trilogy, El Amor Brujo, feels darker, more elemental, and more spiritual than its predecessors. Drawing from Manuel de Falla’s ballet, the film enters a realm of haunting and possession.

Here, flamenco becomes not just expression, but invocation. Ghosts are not metaphors; they are forces that inhabit the space of the dance. Love is not a choice; it is a curse.

What distinguishes El Amor Brujo is its emotional rawness. Where Blood Wedding is formal and Carmen is reflexive, this film feels almost primal. The choreography is less ornamental, more percussive. The music is ritualistic. The space feels enclosed, claustrophobic, charged.

Saura’s cinema here abandons even the minimal scaffolding of rehearsal and performance. The film exists in a liminal zone—neither stage nor reality, neither myth nor psychology.

For the cinephile, El Amor Brujo feels like the logical endpoint of Saura’s experiment. Cinema has been stripped of narrative justification. What remains is pure intensity.

This is cinema as trance.

Style as Ethics

One of the most striking aspects of Saura’s Flamenco Trilogy is its ethical dimension. These films do not exploit flamenco as exotic spectacle. They do not explain it for outsiders. They demand respect through immersion.

Saura collaborates closely with dancers and musicians, allowing their art to dictate cinematic form rather than bending it to narrative convenience. This is not auteurism as domination, but as listening.

The camera is rarely aggressive. It does not cut to impose meaning. It observes, follows, waits. In doing so, Saura aligns himself with a lineage of filmmakers who treat cinema as an act of attention rather than control.

For cinephiles accustomed to the director as omnipotent architect, this humility is revelatory.

The Trilogy’s Place in Film History

The Flamenco Trilogy occupies a unique position in art cinema. It does not belong neatly to musical cinema, experimental cinema, documentary, or narrative fiction. It exists between categories, and in doing so, expands them.

Its influence can be felt in later dance films, performance documentaries, and hybrid forms that reject rigid classification. More importantly, it demonstrates that national culture need not be confined to realism or folklore to be authentic.

Saura’s films show that tradition can be modern without dilution, and that modernism need not reject the past to be radical.

For Spanish cinema, the trilogy marks a moment of cultural reclamation—an assertion of identity after decades of repression. For world cinema, it offers a model of how form itself can carry historical memory.

Discovering Saura as a Cinephile

Encountering Saura’s Flamenco Trilogy as a cinephile already versed in stylized cinema is both grounding and destabilizing. It confirms that cinema can still surprise—not through novelty, but through sincerity of form.

These films do not ask to be decoded. They ask to be felt. They do not explain flamenco. They trust it.

In an era saturated with images, Saura reminds us that cinema’s deepest power lies not in spectacle, but in presence.

Watching the Flamenco Trilogy is not about learning a story. It is about learning how to watch differently—how to listen with the eyes, how to accept that meaning sometimes arrives through rhythm, not reason.

That lesson lingers long after the final footstep fades.