Introduction

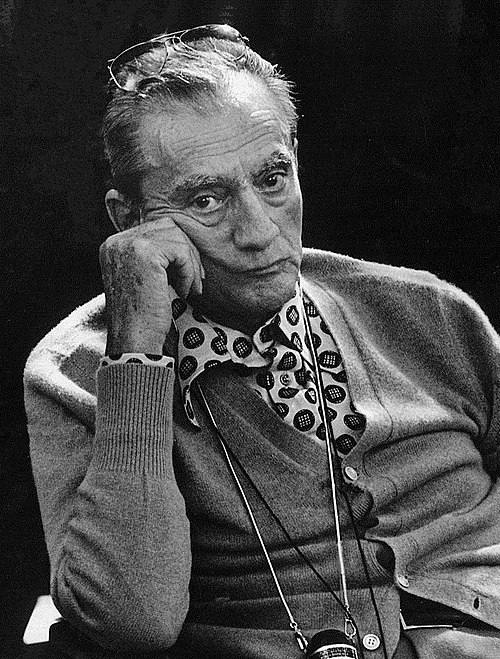

Among the great names of world cinema, Luchino Visconti di Modrone (1906–1976) holds a singular place. Born into an aristocratic Milanese family, Visconti combined a background of privilege and cultural refinement with a radical political and artistic vision. Over a career spanning three decades, he directed some of the most ambitious and aesthetically sophisticated films in Italian and European cinema.

Visconti’s work defies easy categorization. He was a founder of Italian Neorealism, directing one of its earliest and most influential films, Ossessione (1943). Yet he soon expanded beyond the movement, developing a highly personal style that combined operatic grandeur with acute psychological realism. His films oscillate between intimate portrayals of working-class struggle and lavish depictions of aristocratic decadence, but always with a consistent eye for the forces of history, class, and desire.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Visconti’s career, his role in shaping Neorealism, his stylistic evolution, his most successful films, and his enduring impact on cinema.

Early Life: An Aristocrat with Radical Leanings

Luchino Visconti was born on November 2, 1906, into one of Italy’s most distinguished noble families. The Visconti lineage dated back to the rulers of Milan in the Middle Ages, and his father was the Duke of Modrone. The family owned palaces in Milan and estates in Lombardy. Luchino grew up surrounded by wealth, music, and art.

From an early age, Visconti was immersed in culture. He studied music, particularly opera, and developed a passion for theater. He was also drawn to literature, especially French and Russian novelists. His refined upbringing, however, was coupled with a rebellious spirit. By the 1930s, Visconti had gravitated toward leftist politics, sympathizing with the anti-fascist cause despite his aristocratic background.

His entry into cinema came when he moved to Paris in the late 1930s, where he worked as an assistant to Jean Renoir, one of the great humanist directors of French cinema. Renoir’s influence—his blend of realism, compassion, and political awareness—left a lasting mark on Visconti.

The Birth of Italian Neorealism

Visconti’s directorial debut, Ossessione (1943), is widely considered the first true film of Italian Neorealismo. Based loosely on James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, the film tells the story of a drifter and a married woman who embark on a passionate affair that leads to murder.

What set Ossessione apart was its raw realism. Shot on location in the Po Valley, it rejected the glossy artifice of Fascist-era “white telephone” films. Its characters were poor, sweaty, morally ambiguous, and entirely human. The film’s sensuality and frank portrayal of adultery shocked Italian audiences and outraged Fascist censors, who tried to suppress it.

Ossessione was more than a crime story: it was a revelation of Italy’s hidden social realities, filmed with an earthy intimacy that would define Neorealism. Alongside Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) and De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), Visconti’s debut laid the foundations for a movement that redefined cinema after the war.

Neorealist Masterpiece: La terra trema (1948)

Visconti’s second feature, La terra trema (The Earth Trembles), is another cornerstone of Neorealism. Shot in a Sicilian fishing village with non-professional actors speaking in dialect, it depicts the struggles of poor fishermen exploited by wholesalers.

The film is monumental in scale and ambition. Drawing inspiration from Giovanni Verga’s novel I Malavoglia, Visconti combined ethnographic detail with Marxist analysis. He portrays the villagers’ poverty with compassion but also frames their plight within larger structures of class and exploitation.

Unlike De Sica’s more universal humanism, Visconti’s Neorealism was explicitly political, shaped by his Marxist convictions. He emphasized not just the hardships of the poor but the systemic forces that perpetuated inequality.

Though La terra trema was not a commercial success, it remains one of the purest expressions of Neorealist theory and practice.

Stylistic Evolution: From Realism to Operatic Spectacle

By the 1950s, Visconti began moving beyond the strict tenets of Neorealism. His background in theater and opera increasingly shaped his films, which became more stylized, ornate, and psychologically complex.

Senso (1954)

A turning point was Senso, a lavish historical melodrama set during the Austrian occupation of Italy in the 1860s. The film tells the story of an aristocratic woman (Alida Valli) who has a doomed love affair with an Austrian officer (Farley Granger).

With its operatic tone, sumptuous costumes, and rich color cinematography, Senso marked Visconti’s embrace of spectacle and melodrama. At the same time, it retained his Marxist perspective, using the personal tragedy of its characters to comment on class betrayal and the failures of the Italian aristocracy.

Critics were divided, but Senso proved that Visconti could combine political critique with aesthetic grandeur, inaugurating a new phase of his career.

Rocco e i suoi fratelli (Rocco and His Brothers, 1960)

Visconti’s Rocco e i suoi fratelli blends Neorealist elements with operatic melodrama. The film follows a poor southern Italian family that migrates to Milan in search of work. Through the struggles of the five brothers—especially Rocco (Alain Delon) and Simone (Renato Salvatori)—the film explores themes of migration, family bonds, violence, and social disintegration.

With its mix of gritty realism and heightened emotional intensity, Rocco epitomizes Visconti’s mature style. It also introduced Visconti to international audiences, influencing directors from Francis Ford Coppola to Martin Scorsese.

Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1963)

Perhaps Visconti’s greatest masterpiece, Il Gattopardo, adapts Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel about the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy during the Risorgimento. Starring Burt Lancaster, Claudia Cardinale, and Alain Delon, the film is a meditation on history, class, and the inevitability of change.

Visconti, himself an aristocrat, imbues the film with a poignant awareness of his class’s decline. The famous ballroom sequence—nearly an hour long—is one of the most stunning set pieces in film history, encapsulating both the beauty and decadence of a world on the verge of extinction.

Winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes, The Leopard cemented Visconti’s reputation as a cinematic painter of history.

Later Films: Decadence and Death

In his later career, Visconti turned increasingly to themes of decline, corruption, and mortality.

- La caduta degli dei (The Damned, 1969): A lurid, operatic tale of a German industrial family’s complicity in Nazism.

- Morte a Venezia (Death in Venice, 1971): A haunting adaptation of Thomas Mann’s novella, starring Dirk Bogarde as an aging composer obsessed with youthful beauty.

- Ludwig (1972): A four-hour portrait of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, exploring madness, beauty, and political futility.

- Gruppo di famiglia in un interno (Conversation Piece, 1974): A chamber drama about an aging intellectual confronted by disruptive intruders, reflecting Visconti’s own frailty late in life.

These films, often criticized as decadent or excessive, are in fact consistent with Visconti’s lifelong fascination with the intersection of beauty, history, and decay.

Themes and Style

Visconti’s cinema is characterized by several recurring features:

- Class Consciousness: From fishermen in Sicily to aristocrats in Palermo, Visconti consistently examined the structures of class and the passage of history.

- Operatic Aesthetics: A lover of opera, Visconti infused his films with grandeur, spectacle, and heightened emotion.

- Historical Vision: His works often portray social transformation, the decline of old orders, and the emergence of new forces.

- Psychological Depth: Even in large-scale spectacles, he remained attentive to intimate emotions, desires, and conflicts.

- Realism and Artifice: Visconti uniquely combined documentary-like realism with highly stylized mise-en-scène, bridging Neorealism and operatic cinema.

Visconti and Neorealism: Contribution and Departure

Visconti was both a pioneer and a departure point for Neorealism. His Ossessione and La terra trema were foundational texts of the movement, but he soon broke with its constraints, seeking to merge realism with spectacle and to explore the psychological and historical dimensions of his subjects.

His divergence from strict Neorealism reflects his complex identity: an aristocrat turned Marxist, a realist with an operatic sensibility, a historian with a flair for melodrama.

International Recognition and Influence

Visconti’s films won major awards, including the Palme d’Or (The Leopard), Golden Lion (Bellissima, 1951, shared), and Academy Award nominations. More importantly, his influence spread worldwide:

- Martin Scorsese cited Rocco and His Brothers as a formative influence.

- Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather owes much to The Leopard’s depiction of family, tradition, and power.

- Bernardo Bertolucci and Pier Paolo Pasolini drew from Visconti’s combination of politics and aesthetics.

- German New Wave directors admired The Damned for its fearless depiction of history and decadence.

Legacy and Death

Visconti suffered a stroke in 1972, which left him partially paralyzed, but he continued to work until his death in 1976. He died in Rome on March 17, 1976, at the age of 69.

His legacy is immense: he bridged Neorealism and modernist spectacle, influenced generations of filmmakers, and left behind a body of work that remains essential for understanding the evolution of cinema in the 20th century.

Conclusion: The Aristocrat of Decay and Desire

Luchino Visconti was a paradox: an aristocrat who championed the poor, a realist who reveled in artifice, a Marxist who mourned the passing of his own class. His films reflect this tension, oscillating between gritty realism and sumptuous melodrama, between social critique and aesthetic indulgence.

More than any other Italian director, Visconti understood cinema as a theater of history, where the fates of individuals are bound to the rise and fall of classes, empires, and ideals. His films confront beauty and mortality, desire and decay, with unmatched rigor and elegance.

Today, nearly half a century after his death, Luchino Visconti remains not only one of the greatest Italian directors but also one of the central figures in world cinema—a filmmaker who gave us both the intimacy of a poor fisherman’s struggle and the grandeur of an aristocratic ballroom, always with the same deep compassion for the human condition.