Michael Cacoyannis (1922–2011) is one of the most significant filmmakers to emerge from Greece—yet calling him merely a “Greek filmmaker” feels like a limitation. His cinema is a bridge: between classical tragedy and modern storytelling, between Cypriot roots and international acclaim, between the intimate emotional landscapes of the Mediterranean and the grand narratives of universal human experience. To watch his films today is to see Greek cinema in its purest—and paradoxically most global—form.

Cacoyannis belongs to that rare generation of directors who drew deeply from their national culture yet spoke with a voice that the world instantly understood. And while many cinephiles know him primarily through Zorba the Greek (1964), the reality is richer, more textured, and more ambitious. His body of work—particularly his iconic trilogy of Greek tragedies and his collaborations with Irene Papas—remains a monumental pillar of both Greek art and world cinema.

This article explores his life, his vision, his achievements, and his lasting impact with the depth and nuance he deserves.

I. Early Life: A Mediterranean Identity Shaped by Movement

Michael Cacoyannis was born in Limassol, Cyprus, at a time when the island was still under British rule. His upbringing was steeped in Greek language and culture, but life in Cyprus brought a rich blend of influences—colonial British administration, Mediterranean multiculturalism, Orthodox tradition, and the Cypriot spirit of storytelling.

This hybrid identity is key to understanding Cacoyannis.

His cinema is proudly Greek yet cosmopolitan, passionate yet disciplined, emotional yet philosophical. His early life created a filmmaker who could straddle two worlds: the local and the universal.

During World War II, he moved to England to study law, but London during wartime exposed him to theater, radio, and the power of dramatic storytelling. He eventually abandoned law for the arts, joining the Old Vic School in London—a crucial shift. British theatrical training sharpened his dramatic instincts and taught him structure. Greek culture, which he carried naturally, gave him soul.

The combination is visible in every frame he ever shot.

II. From Theater to Film: A New Voice in Greek Cinema

When Cacoyannis moved to Greece in the early 1950s, the country’s film industry was limited, often dominated by melodramas, comedies, and local popular cinema. Greek directors who sought international recognition were few and often lacked state support.

Cacoyannis entered the scene with a different ambition.

He wanted to create Greek stories that resonated globally—not by diluting their Hellenic identity, but by presenting it with artistic conviction and authenticity. His debut feature, Windfall in Athens (1954), achieved modest success, but it was his second film, Stella (1955), that marked him as a force.

“Stella”: A New Kind of Greek Tragedy

Starring Melina Mercouri, Stella is both modern and mythic. It takes a familiar theme—love, pride, and fate—and presents it with boldness and cinematic clarity. The story of an independent nightclub singer who refuses to submit to societal expectations, even at great personal cost, felt like a modern-day Greek tragedy, wrapped in realism but elevated by symbolism.

The film premiered at Cannes, gaining international attention.

Greek cinema had a new ambassador.

III. Before Zorba: The Foundation of a Master

Before reaching global fame with Alexis Zorbas, Cacoyannis developed a strong portfolio of films that established his thematic concerns:

- the tension between fate and choice

- the burden of family

- the oppressive weight of tradition

- the Mediterranean landscape as emotional environment

“A Girl in Black” (1956)

Shot on Hydra, this film is one of the jewels of Greek cinema’s early art movement. It portrays a young woman (Eleni Zafeiriou) persecuted by gossip and tragedy in a small island community. The film’s naturalistic style and sharp social commentary were groundbreaking for the era.

“A Matter of Dignity” (1958)

A portrait of a bourgeois Athenian family collapsing under financial pressure, this film showcased Cacoyannis’s ability to move fluidly between the personal and the social. It offered a harsh critique of class pretensions within Greece—a theme that would recur in his work.

IV. “Alexis Zorbas”: The Masterpiece That Changed Everything

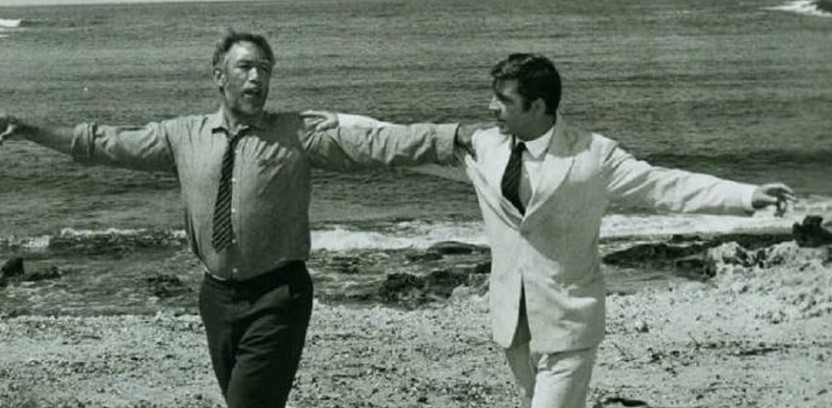

When Zorba the Greek (or Alexis Zorbas, as it’s known in Greek) premiered in 1964, it was more than a film. It was a cultural moment—one that shaped global perceptions of Greece for generations. Even today, the iconic image of Anthony Quinn dancing on the beach remains one of cinema’s most enduring visual metaphors for resilience, freedom, and the complexity of the human spirit.

Adapting Kazantzakis

Kazantzakis’s novel is philosophical, introspective, and dense with metaphysical reflection. Cacoyannis brilliantly streamlined the narrative without losing its soul. He turned complex internal dialogues into cinematic action, allowing images to carry existential weight.

The Craftsmanship Behind the Masterpiece

Casting

- Anthony Quinn: Quinn’s Zorba is larger-than-life yet authentically grounded. Cacoyannis knew Quinn’s intensity could carry the character’s mix of joy and sorrow.

- Alan Bates: As the introverted writer, Bates becomes the perfect counterbalance to Quinn’s fiery energy.

- Irene Papas: In the crucial role of the widow, Papas embodied dignity, sensuality, and tragic inevitability. Her performance is one of the film’s emotional pillars.

Cinematography

Walter Lassally’s black-and-white photography is a study in contrasts—sunlight and shadow, freedom and repression, hope and destruction.

Music

Mikis Theodorakis’s score, especially the legendary “Zorba’s Dance,” gave the film its heartbeat. Cacoyannis’s skill was not only in directing actors but in orchestrating all the artistic elements into a cohesive emotional experience.

Oscar Nominations & Global Recognition

Zorba the Greek earned seven Academy Award nominations, including:

- Best Director (Michael Cacoyannis)

- Best Picture

- Best Actor (Anthony Quinn)

- Best Supporting Actress (Lila Kedrova, who won)

This was an unprecedented moment in Greek cinema. A filmmaker from Cyprus, working largely outside Hollywood, had created a global sensation rooted in Greek culture. The film also won Lassally an Oscar for Best Cinematography.

More importantly, it placed Greek cinema on the international map in a way no film had before.

V. Irene Papas: A Collaboration of Fire and Soul

Few director-actor partnerships in European cinema carry the emotional charge of Cacoyannis and Irene Papas. Their collaboration spanned decades and produced some of the most unforgettable portrayals of female strength, vulnerability, and tragic depth in 20th-century film.

Papas had a presence that was almost mythical. Her face—angular, expressive, timeless—carried the weight of ancient tragedy. Cacoyannis understood this instinctively. He used her not simply as an actress, but as an emblem of Hellenic womanhood.

Major Collaborations

- “Electra” (1962)

Papas delivers one of her greatest performances as Euripides’ Electra. Her fury, grief, and moral conviction radiate through the screen. - “Zorba the Greek” (1964)

As the widow, Papas’s silent dignity and tragic fate serve as the film’s emotional hinge. - “The Trojan Women” (1971)

Alongside Katharine Hepburn and Vanessa Redgrave, Papas stands out with raw emotional energy. - “Iphigenia” (1977)

Here Papas plays Clytemnestra, a mother torn between duty, love, and divine manipulation.

Their collaborations embody the fusion of ancient Greek drama with modern cinematic language.

Thematic Synergy

Cacoyannis’s themes—fate, sacrifice, the cruelty of social judgment—found their perfect vehicle in Papas. She became the tragic conscience of his filmography.

VI. The Greek Tragedy Trilogy: Cinema Meets Antiquity

If Zorba made Cacoyannis a global name, his trilogy of Greek tragedies made him a cultural monument.

1. “Electra” (1962)

Adapted directly from Euripides, it preserves the power of ancient theater while using cinematic tools—close-ups, landscape framing, rhythm—to deepen emotional impact.

This film won the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Cinematic Transposition, marking the first major international recognition of Cacoyannis’s unique ability to modernize antiquity without distorting it.

2. “The Trojan Women” (1971)

An international co-production with a stellar cast (Hepburn, Papas, Redgrave), this film remains one of the most faithful and powerful adaptations of Euripides ever put on screen.

Shot during a period of political turbulence in Greece (the military junta era), the film’s anti-war message resonated deeply.

Its tone—somber, intense, uncompromising—showcases Cacoyannis’s capacity for moral cinema.

3. “Iphigenia” (1977)

Perhaps the most cinematic of the trilogy, Iphigenia binds ancient tragedy with political commentary. The story of a girl sacrificed for the sake of national pride mirrors the cost of war and authoritarianism.

It earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, cementing Cacoyannis’s standing as one of the foremost interpreters of Greek tragedy.

VII. Later Career and International Work

Cacoyannis’s later career saw him branching out into English-language projects and theatrical productions.

“The Day the Fish Came Out” (1967)

A satirical, colorful, experimental work, far removed from his earlier naturalistic style. Though controversial at release, it has since gained cult admiration for its boldness.

Theater Work

His theatrical productions in London, New York, and Athens—including adaptations of Shakespeare, Chekhov, and classical Greek plays—reflect his lifelong commitment to drama in all forms.

“Sweet Country” (1987)

A political drama set during the Chilean coup, showing that Cacoyannis remained globally engaged and morally driven.

VIII. Themes and Style: What Made Cacoyannis Unique?

1. The Mediterranean as Emotional Landscape

For Cacoyannis, the Aegean was not merely a backdrop—it was a character.

His locations breathe:

- the harsh cliffs of Crete

- the serene waters of Hydra

- the dusty fields of Argolis

These landscapes frame human destinies and reflect internal conflicts.

2. Women as Heroes of Tragedy

From Electra to Clytemnestra, from Irene Papas’s widow to the suffering mothers of The Trojan Women, Cacoyannis consistently placed female characters at the moral core of his narratives.

3. Tragedy as a Lens on Modern Life

His films—whether based on Euripides or not—carry the weight of myth. Choices have consequences. Pride leads to downfall. Human desire clashes with fate.

4. Moral Courage and Social Critique

Cacoyannis confronted:

- hypocrisy

- patriarchal oppression

- authoritarian power

- class structure

- nationalism

He was not a propagandist; he was a humanist.

IX. Impact and Legacy

1. Opening the Door for Greek Cinema

Before Cacoyannis, Greek films rarely traveled abroad.

After Zorba, international festivals and distributors began actively seeking Greek cinema.

Directors like Theo Angelopoulos, Pantelis Voulgaris, and later Yorgos Lanthimos benefited from the global pathways he helped shape.

2. Defining Greekness for the World

His cinema became the archetype of Greek emotional expression—passionate, tragic, life-affirming.

Yet he avoided stereotypes, presenting Greece as complex and morally challenging.

3. Elevating Ancient Drama for Modern Audiences

Cacoyannis proved that ancient Greek tragedy was not academic relic but living art. His adaptations remain benchmarks in film schools and theater programs worldwide.

4. A Model of Cultural Ambassadorship

Cacoyannis became a Greek cultural ambassador not through diplomacy but through art. His films shaped the world’s emotional connection to Greek identity.

X. Conclusion: Michael Cacoyannis’s Cinema Still Breathes

Michael Cacoyannis’s work remains as vital today as when it first premiered.

His films do not age; they resonate. His characters do not fade; they reflect our own dilemmas. His landscapes do not merely decorate; they speak.

To watch Cacoyannis today is to witness the spirit of Greek tragedy living in modern form, infused with Mediterranean passion, moral clarity, and artistic courage. It is to encounter a cinema that is both deeply national and profoundly universal.

Most importantly, his masterpiece Alexis Zorbas continues to remind viewers that life—like cinema—is a dance between joy and sorrow, freedom and fate, love and loss. And that in that dance, we discover who we truly are.

Pingback: Michael Cacoyannis’ Trojan Trilogy: A Cinematic Testament to Ancient Greek Tragedy - deepkino.com