Introduction

Michael Haneke is one of the most provocative and uncompromising auteurs in contemporary cinema. Born on March 23, 1942, in Munich, Germany, and raised in Austria, Haneke has crafted a body of work that interrogates the moral and psychological decay of modern society. His films are characterized by their austere visual style, meticulous framing, and unflinching depictions of violence—both physical and emotional. Unlike many filmmakers who use violence for spectacle, Haneke employs it as a tool for critique, forcing audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about human nature, media desensitization, and societal complicity.

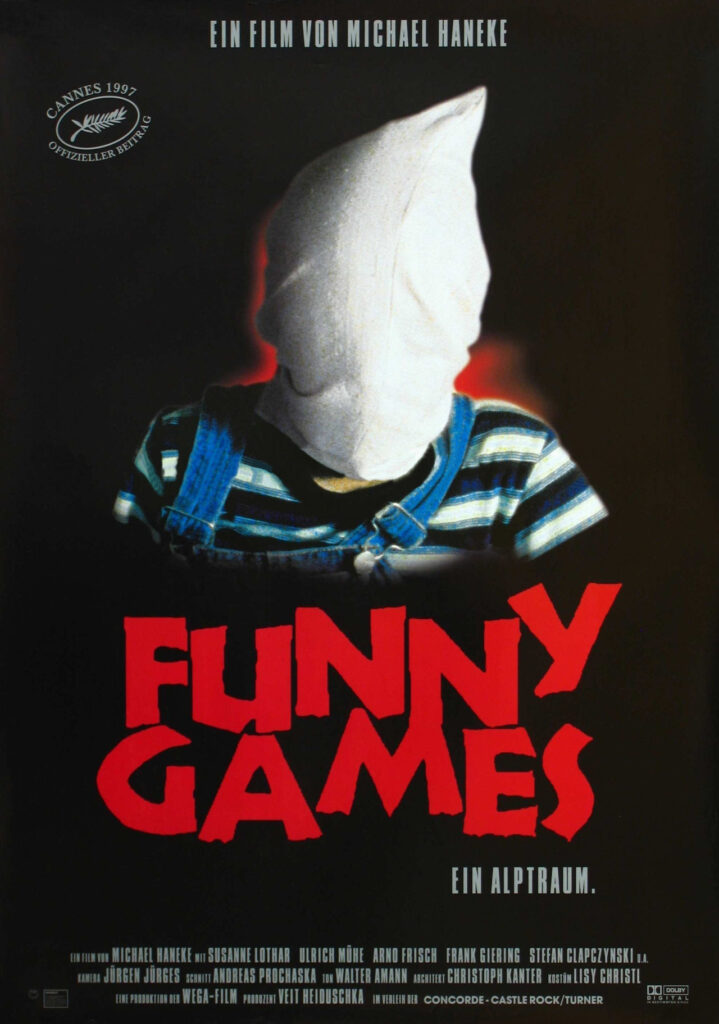

Haneke’s filmography spans over four decades, including masterpieces like Caché (2005), Amour (2012), The White Ribbon (2009), Funny Games (1997/2007), and The Seventh Continent (1989). His work has earned him numerous accolades, including two Palmes d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, making him one of the most decorated European filmmakers of his generation.

This article will explore Haneke’s filmmaking style, his unique approach to violence, his narrative techniques, his major works, and his lasting influence on cinema.

Haneke’s Filmmaking Style: Clinical Precision and Emotional Detachment

Haneke’s directorial approach is marked by a deliberate coldness, often described as “clinical” or “Kubrickian.” His films avoid conventional emotional manipulation, opting instead for a detached, almost anthropological observation of human behavior. Key elements of his style include:

1. Long Takes and Static Shots

Haneke frequently employs long, uninterrupted takes, forcing the audience to sit with discomfort. Scenes unfold in real-time, heightening tension without resorting to rapid editing. In Caché, a single static shot of a Parisian street becomes unbearably suspenseful as the viewer scans the frame for hidden threats.

2. Off-Screen Violence

Unlike Hollywood’s graphic depictions, Haneke often leaves violence off-screen, making it more disturbing through implication. In Funny Games, the brutal murder of a child occurs just outside the frame, with only the sound of a gunshot confirming the act. This technique forces the audience’s imagination to fill in the gaps, making the violence more psychologically impactful.

3. Brechtian Distancing

Haneke employs Brechtian techniques to prevent emotional immersion, reminding viewers they are watching a constructed reality. In Funny Games, one of the killers breaks the fourth wall, addressing the audience directly: “You’re on their side, aren’t you?” This shatters the illusion of passive spectatorship, implicating the viewer in the film’s violence.

4. Ambiguity and Open Endings

Haneke’s films often refuse clear resolutions, leaving key questions unanswered. Caché ends with an enigmatic shot of two characters meeting, their relationship unexplained. This ambiguity forces active engagement, as viewers must interpret the meaning themselves.

Haneke’s Approach to Violence: A Critique of Spectatorship

Haneke’s treatment of violence is central to his work. He rejects the glorification of brutality seen in mainstream cinema, instead presenting it as banal, senseless, and deeply unsettling. His films explore how media consumption desensitizes audiences to real suffering.

1. Violence as Structural Critique

In Funny Games, Haneke critiques the audience’s appetite for on-screen brutality. The film mirrors the structure of a thriller but denies catharsis—the villains win, and the victims suffer pointlessly. The 2007 American remake, shot identically to the original, underscores Haneke’s belief that Hollywood commodifies violence for entertainment.

2. The Banality of Evil

The White Ribbon examines the roots of fascism through the lens of a pre-WWI German village. Violence here is systemic—children are abused, animals are mutilated, and cruelty is normalized. Haneke suggests that the seeds of Nazism were sown in everyday sadism and authoritarian upbringing.

3. Psychological Violence

Haneke’s most disturbing moments are often psychological. In Amour, an elderly man suffocates his dementia-stricken wife out of love—a act of mercy that is also a murder. The horror lies not in gore but in the moral ambiguity of the decision.

Haneke’s Screenwriting: Economy, Subtext, and Moral Dilemmas

Haneke’s scripts are meticulously constructed, with every line and silence serving a purpose. His writing is sparse, avoiding exposition in favor of subtext.

1. Minimalist Dialogue

Characters in Haneke’s films often speak in banalities, masking deeper tensions. In The Seventh Continent, a family’s mundane routines precede their collective suicide—their inability to articulate despair makes their actions more chilling.

2. Moral Ambiguity

Haneke refuses easy judgments. In Caché, Georges (Daniel Auteuil) may or may not be guilty of past racism, but Haneke leaves it unresolved, forcing the audience to grapple with their own biases.

3. Repetition and Ritual

Routine is a recurring motif, underscoring the emptiness of modern existence. The robotic daily rituals in The Seventh Continent mirror the characters’ emotional numbness before their shocking finale.

Masterpiece Analyses: Haneke’s Major Works

1. The Seventh Continent (1989)

Haneke’s debut feature is a harrowing study of alienation. Based on a true story, it follows a middle-class family who methodically destroy their possessions before committing suicide. The film’s cold detachment makes their actions even more unsettling.

2. Funny Games (1997/2007)

A meta-commentary on violence in media, Funny Games traps viewers in a sadistic home invasion with no escape. The film implicates the audience for deriving pleasure from fictional suffering.

3. Caché (2005)

A psychological thriller about guilt and colonial legacy, Caché follows a man terrorized by anonymous surveillance tapes. The film’s unresolved mystery critiques France’s denial of its racist past.

4. The White Ribbon (2009)

Shot in stark black-and-white, this pre-WWI drama examines the origins of fascism through village children raised under abusive discipline. The film suggests cruelty is cyclical.

5. Amour (2012)

Haneke’s most emotionally direct film, Amour depicts an elderly couple facing mortality. The film’s tenderness contrasts with its unflinching look at euthanasia, earning Haneke his second Palme d’Or.

Haneke’s Role in European Cinema and Legacy

Haneke is a defining figure of the New European Cinema, alongside Lars von Trier and the Dardenne brothers. His influence is seen in:

- The “Slow Cinema” Movement – Directors like Béla Tarr and Nuri Bilge Ceylan share Haneke’s preference for long takes and existential themes.

- Post-Haneke Thrillers – Films like Prisoners (2013) and The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) borrow his clinical approach to violence.

- Moral Cinema – Haneke’s insistence on ethical engagement has inspired filmmakers to challenge audiences rather than placate them.

Conclusion: The Uncomfortable Truths of Haneke’s Cinema

Michael Haneke’s films are not meant to entertain in the traditional sense—they are meant to unsettle, provoke, and indict. His work forces viewers to confront their own complicity in societal violence, whether through passive media consumption or historical denial. By refusing catharsis and embracing ambiguity, Haneke denies easy answers, instead demanding introspection.

In an era of escapist cinema, Haneke remains a necessary counterforce—a filmmaker who holds up a mirror to society’s darkest impulses and asks: What are you willing to see? His legacy is one of uncompromising moral inquiry, ensuring his place among cinema’s most important auteurs.