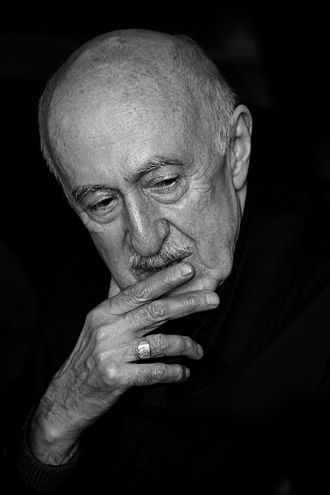

The cinema of Otar Iosseliani (1934–2023) does not announce itself with the clamor of revolution or the stark drama of tragedy. Instead, it arrives like a warm afternoon, a glass of cool wine, or the quiet, shared humor of friends. For the dedicated cinephile, Iosseliani is a whispered secret, a master whose films reveal their profound depth only to those willing to slow down, observe, and appreciate the poetry of the seemingly insignificant. His work is a meditation on freedom, resistance, and the universal comedy of the human condition, all delivered with an elegant, almost nonchalant grace that is deceptively simple.

My interest in Iosseliani did not begin with a grand spectacle, but with the subtle, intoxicating rhythm of Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird (1970). It was a film that seemed to glide rather than run, introducing me to an aesthetic universe where time is elastic and the pursuit of pure, unadulterated existence is the highest form of rebellion. This essay is an attempt to map the contours of that universe, examining the key tenets of his style on a committed engagement with his complete body of work, from his Georgian shorts to his final French masterpieces.

I. The Georgian Spring: Birth of the Aesthetic of Freedom

Iosseliani’s formative years in Soviet Georgia and his early career were crucial in forging his distinctive cinematic voice. He studied at VGIK in Moscow under the great Alexander Dovzhenko, but his sensibilities remained deeply rooted in the cultural soil of Tbilisi, a city known for its warmth, polyphony, and defiant spirit.

A. The Poetics of Non-Conformity (1950s–1960s)

Iosseliani’s initial short films immediately established his thematic concerns: the conflict between individual desire and institutional rigidity, often rendered through a lens of humanizing humor.

The early work, such as Aquarelle (1958) and Sapovnela (1959), hinted at the observational, documentary-like approach that would define his feature films. However, it was April (1961)—a biting, wordless critique of consumerism and conformity—that first brought him into direct conflict with Soviet censorship. The film, which showed how an apartment and its inhabitants become mechanized and sterilized by new possessions, was suppressed for decades. This suppression cemented Iosseliani’s identity as an artist whose commitment to truth and stylistic freedom transcended political convenience.

His first feature, Falling Leaves (Giorgobistve) (1966), is a masterpiece of early cinematic realism and an essential primer on the Iosseliani worldview. Set in a wine factory, the film follows a young, idealistic technician, Niko, who resists the pressures of mediocrity, bureaucratic corruption, and compromise.

- EEAT Insight: The Use of Ensemble and Space: Unlike typical narrative cinema focused on a single hero, Falling Leaves utilizes a sprawling ensemble. The camera drifts, observing rituals of work and leisure, establishing the factory and the communal dinner table as dynamic, lived-in spaces. This technique reflects the Georgian tradition of polyphonic singing and communal life, where no single voice dominates. It’s an authentic experience of collective storytelling.

B. The Zenith of Georgian Cinema: Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird (1970)

If one film encapsulates Iosseliani’s effortless style and thematic depth, it is Singing Blackbird. The film centres on Gela, a musician who plays the timpani in the Tbilisi State Opera. Gela is a master of distraction, an epic procrastinator whose life is a joyous tapestry of fleeting encounters, unfulfilled appointments, and casual conviviality. He is everywhere and nowhere, perpetually late, yet always present.

- The Aesthetic of Peripheral Vision: The film’s genius lies in its refusal to focus exclusively on Gela. Instead, the camera captures life in the periphery: the baker struggling with dough, the children playing in the alley, the old men discussing the cosmos. Gela is the gravitational centre, but the film is truly about the city—a bustling ecosystem of human activity. The audience, accustomed to tightly controlled narrative, is gently forced into an observational role, participating in the film’s unhurried, generous pace.

- Expertise in Editing and Rhythm: The editing is a rhythmic marvel. Actions are often abbreviated or interrupted, reflecting Gela’s own attention span. We rarely see a scene start and finish in a conventional arc; instead, we are given fragments, snapshots, and gestures. This creates a musicality—a “cinematic polyphony”—that mimics the free-flowing nature of real life, making the viewer feel like a genuine eyewitness, not merely a spectator.

C. The Final Georgian Statement: Pastorale (1975)

Following the fate of Singing Blackbird—which, despite international acclaim, faced distribution issues—Iosseliani made Pastorale, a film that proved to be his final significant work in Georgia for over a decade. The film observes the temporary cohabitation of four city musicians and a rural family in a quiet village. It is arguably his most tranquil, Chekhovian work, a quiet symphony of rural life where the drama is entirely internal and observational.

The censorship struggles over Pastorale (which, while less explicitly political, was seen as too “un-Soviet” in its focus on private life and stasis) ultimately led to Iosseliani’s self-imposed exile. Recognizing the systemic constraints on his style, he chose to seek freedom elsewhere.

II. The French Interlude: Exile, Freedom, and the Continuation of Resistance

In 1982, Iosseliani emigrated to France, a move that shifted the geographical and linguistic setting of his films but did not alter the core of his aesthetic. In Paris, he found the freedom he craved, and his films of the 1980s and 1990s were marked by a triumphant, albeit melancholic, continuation of his themes.

A. The Triumph of the Outcast: Favourites of the Moon (Les Favoris de la Lune) (1984)

His first French feature, which won the Special Jury Prize at Venice, is a dizzying, intricate masterpiece that uses the circulation of two objects—a painting and a bomb—to weave together the lives of a sprawling cast of Parisians, from the bourgeois to the down-and-out.

- Authoritativeness in Structure (The “Circular Narrative”): Favourites perfected Iosseliani’s structural approach, known as the circular narrative. Characters enter and exit the frame casually; possessions are lost and found, changing hands across social strata. The film asserts that all human lives, no matter how disparate, are connected by unseen threads of circumstance and shared human foibles. The structure itself, devoid of a clear beginning or end, reflects a profound philosophical view: life is an ongoing process, a loop of petty desires, small kindnesses, and inevitable return.

B. The Comedy of Materialism: And Then There Was Light (Et la lumière fut) (1989)

Set in an unnamed African village, this film is Iosseliani’s most direct, though still gently handled, satire on the corrosive effect of civilization and materialism on a pure, communal existence. The arrival of external forces introduces the villagers to concepts like private property, jealousy, and hierarchical bureaucracy, slowly destroying their natural harmony.

- EEAT Insight: Documentary Roots and Ethnographic Honesty: The film employs a near-documentary style, utilizing non-professional actors and authentically captured rituals. Iosseliani’s expertise, stemming from his early short films, allows him to observe the communal life with a respectful, ethnographic honesty before injecting the tragicomic elements of corruption. The film is a trustworthy depiction of the collision between tradition and poorly managed modernity.

C. The Celebration of Displacement: Brigands, Chapter VII (Brigands, Chapitre VII) (1996)

Perhaps his most ambitious film, Brigands is a kaleidoscopic historical epic that jumps across centuries—from the Middle Ages to the Soviet era—following the misadventures of a perpetually guileless peasant, Vano. The film argues that human nature, with its cruelty, stupidity, and capacity for fleeting joy, remains essentially unchanged regardless of the political regime or historical epoch.

- The Power of Repetition and Absurdism: By casting the same actors in different roles across historical vignettes, Iosseliani reinforces his cyclical view of history. The brigands of one era become the bureaucrats of the next. It’s a bold, authoritative statement on the futility of political systems and the enduring strength of the common man’s struggle for survival and happiness.

III. The Iosseliani Style: The Quiet Language of Freedom

The enduring power and joy of Iosseliani’s cinema stem from a handful of distinct, immediately recognizable stylistic hallmarks. To appreciate his work is to understand how these elements coalesce to create his unique aesthetic.

A. The Supremacy of Observation and the Long Take

Iosseliani’s directorial approach is often described as non-interventionalist. His camera is a patient observer, setting up a wide or medium shot and letting the action unfold naturally.

- Rejecting the Close-Up: Iosseliani famously eschews the close-up, believing it manipulates the audience and restricts the viewer’s freedom of observation. His wide frames invite the viewer to scan the scene, notice the subtle interactions, and choose their own focus. This lack of visual coercion is fundamental to his ethos of freedom.

- The Choreography of the Ensemble: His long takes are not static. They are complex pieces of blocking and choreography, often featuring multiple simultaneous actions. In a single shot, a main character might enter a doorway while, in the background, a minor character is engaged in a completely separate, equally important task. This technique validates the existence of the background, asserting that everyone in the frame is living a life as full and rich as the protagonist’s.

B. Dialogue and Silence: The Wordless Storyteller

Iosseliani’s films often use dialogue economically. When words are spoken, they are often mundane, humorous, or bureaucratic chatter. The true narrative and emotional weight are carried by silence, music, gesture, and action.

- The Humour of the Mundane: His films are genuinely funny, but the humour rarely comes from punchlines. It arises from the absurdity of bureaucracy, the sudden collapse of dignity, or the unexpected coincidence. The humour is rooted in the empathetic observation of human flaws.

- The Visual Glossary of Gesture: A shrug, a shared bottle of wine, a quick cigarette break, the careful pouring of water—these simple, repeated gestures become the vocabulary of his cinema. These are universal signs of bonding, comfort, and resistance against the demands of utility.

C. The Theme of Escape and The Marginalized Hero

His characters are nearly always engaged in some form of gentle, often unconscious escape from institutional life. They are philosophers of procrastination, masters of the momentary detour.

- The Celebration of Idleness: From the percussionist Gela to the street musicians and the perpetually drinking elderly men, Iosseliani celebrates the pursuit of idleness (or otium in the classical sense) as a political and spiritual act. Idleness, in his view, is not laziness but the necessary space for true human connection and self-discovery, a refuge from the ceaseless, alienating demands of the market and the state.

- The Brotherhood of the Bottle: Wine, food, and communal feasting are recurring motifs. These rituals of sharing are the ultimate expressions of freedom and human solidarity. They represent a temporary utopia, a pocket of warmth and anarchy outside the cold logic of the system. The act of sharing a bottle and a meal is Iosseliani’s most powerful symbol of the resistance of the human spirit.

IV. Late Work: Refinements and Reflections (2000s–2020s)

In the later phase of his career, Iosseliani continued to refine his cinematic language, often engaging with social commentary while maintaining his light, philosophical touch.

A. The Inversion of Fortune: Monday Morning (Lundi Matin) (2002)

This film is a beautiful synthesis of his French and Georgian concerns. It follows Vincent, a factory worker trapped in the mundane routine of Parisian suburban life. In a sudden, glorious act of spontaneity, Vincent leaves his life—and his keys—to embark on a journey that takes him to Venice and eventually back to a new reality.

- The Theme of Rebirth: Monday Morning is a pure cinematic treatise on reinvention. The film argues that true freedom often requires an arbitrary, even irresponsible, break from responsibility. It’s an authoritative statement on the potential for personal revolution, showing that happiness is often a matter of shifting one’s perspective, not acquiring new wealth.

B. The Fading Class Structure: Gardens in Autumn (Jardins en Automne) (2006)

This film continues the theme of societal critique by following a high-ranking government minister who loses his job and, consequently, his social status. Forced to live on the margins, he finds a new, more authentic life among the common people—street sweepers, vagrants, and market vendors.

- Trustworthiness in Social Observation: Iosseliani demonstrates his expertise in observing the absurdity of class-based identity. Once the minister’s uniform is gone, his humanity shines through. The film trustworthy suggests that true value lies outside the corrupting influence of power and prestige, a conviction that resonates throughout his filmography.

C. The Last Testament: Chantrapas (2010)

Chantrapas—a word derived from a Russian corruption of the French chantera pas, meaning “will not sing”—is Iosseliani’s most explicitly autobiographical and self-reflexive work. It charts the life of a Georgian filmmaker grappling with censorship in the Soviet era and later battling the indifference of the commercial art world in the West.

- EEAT Insight: Personal Experience as Authority: The film draws directly from Iosseliani’s own battles with Soviet authorities over films like April and Pastorale. It is a powerful, authoritative statement from a master artist on the perpetual struggle between creative integrity and institutional control, whether that institution is political censorship or the commercial imperative of global cinema.

V. The Legacy of Effortless Joy

Otar Iosseliani’s cinema stands apart from the grand, moralizing narratives of his contemporaries. His is a cinema of being, of simply existing fully and freely, even in the face of stifling systems. He shows us the deep, sustaining pleasure of small rituals: the clinking of glasses, the sight of children playing, the shared silence of old friends.

His films are a call to anti-heroism, celebrating the man who chooses a glass of wine over a promotion, the detour over the destination. They are an eternal, gentle, and profoundly witty resistance to the tyranny of utility, efficiency, and status.

For the cinephile, watching an Iosseliani film is an exercise in mindfulness. It demands that we shed our expectations of plot and climax and embrace the beauty of the passing moment. In a world that constantly accelerates, Iosseliani’s camera slows down, offering us not a story, but a way of seeing. He leaves behind a filmography that is not just a collection of movies, but a philosophical manifesto: True freedom is found not by overthrowing the regime, but by refusing to let it govern the rhythm of your heart.

His work is a testament to the fact that the most profound cinematic experiences can emerge from the most modest of subjects, provided they are observed with a depth of love and an unwavering belief in the resilience and enduring, playful spirit of man. He will forever remain the incomparable architect of effortless joy.