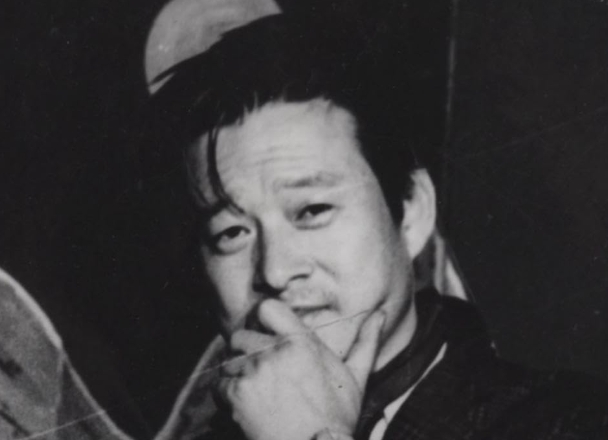

When we speak of Korean cinema’s golden age, we inevitably arrive at the towering figure of Shin Sang-ok—a director whose life story reads like something lifted from one of his own melodramas, except no screenwriter would dare pen something so audacious. Born sometime between 1925 and 1926 in Chongjin, in what is now North Korea, Shin would go on to direct approximately 74 films across five decades, establishing himself as the architect of Korean cinema’s most fertile period and earning the sobriquet that still resonates today: the “Prince of South Korean Cinema.”

For those of us who have spent years excavating the hidden treasures of Asian cinema, Shin Sang-ok represents something rare—a filmmaker who possessed both the commercial instincts of a Hollywood mogul and the artistic vision of an auteur. He wasn’t just making films; he was building an entire industry from the ground up, one frame at a time.

The Making of a Mogul: Early Years and Artistic Formation

Shin’s journey into cinema began in the aftermath of colonization. After studying at Tokyo Fine Arts School (the predecessor of what became Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music), he returned to Korea and found himself working as an assistant production designer on Choi In-kyu’s landmark film “Viva Freedom!” in 1946—the first Korean film produced after independence from Japan. This wasn’t merely an auspicious beginning; it was a baptism into a cinema that was discovering itself, finding its voice in the rubble of occupation.

But it was the 1950s and 1960s—that glorious, tumultuous period—when Shin truly came into his own. The Korean War had left the nation devastated, its cities reduced to ash and memory. Yet from this desolation emerged a cinema of remarkable vitality, and Shin was at its vanguard. He worked with ferocious energy, often directing two or more films per year, establishing a work ethic that would define his career and, arguably, his entire generation of Korean filmmakers.

Shin Films: Building a Kingdom

In founding Shin Films, Shin wasn’t content to be merely a director. He understood, perhaps before anyone else in Korea, that cinema needed infrastructure. During the 1960s alone, his production company churned out around 300 films. This wasn’t assembly-line filmmaking—though the output suggests it might have been—but rather a systematic attempt to create a sustainable Korean film industry that could compete internationally.

The company became known as the “Kingdom of Film,” and advertisements from 1962 show its building crowned with an incense burner symbol, projecting both cultural authenticity and modern ambition. This duality—between tradition and modernity, East and West—would become the defining tension in many of Shin’s greatest works.

The Masterworks: A Cinema of Contrasts

“A Flower in Hell” (1958)

If there’s one film that encapsulates Shin’s ability to merge genre with social commentary, it’s “A Flower in Hell” (Jiokhwa). Shot in stark black-and-white, the film follows Yeong-shik, a petty criminal surviving in post-war Seoul by stealing U.S. military supplies and selling them on the black market. His girlfriend, Sonya—played with magnetic intensity by Choi Eun-hee, Shin’s wife and muse—is a prostitute catering to American soldiers.

What makes this film extraordinary, even by today’s standards, is its refusal to moralize. Shin lived with a sex worker during the Korean War (for reasons of convenience, as housing was scarce), and this experience informed his remarkably neutral stance toward the profession. He doesn’t condemn these women for their choices, nor does he sentimentalize their circumstances. Instead, he presents them as products of their environment—flowers growing in hell, if you will.

The film’s climax is genuinely haunting, with a character trudging through mud and fog in sequences that feel more akin to horror or film noir than melodrama. Critics have noted its kinship with American outsider cinema—particularly Sam Fuller and Edgar Ulmer—but also with the anti-imperialist modernism of Nagisa Oshima. The film wasn’t fully appreciated upon its release, but decades later, it’s recognized as one of the first Korean films to grapple honestly with American military presence and its corrosive effect on Korean society.

The cinematography alone is worth the price of admission—Gang Beom-gu’s camera work captures Seoul as a city of shadows and desperation, where American neon signs cast garish light on Korean poverty. And that final shot, one of the most iconic in Korean cinema history, crystallizes everything the film has been building toward: a moment of violence born from jealousy and desperation, set against the indifferent landscape of post-war survival.

“Mother and a Guest” (1961)

If “A Flower in Hell” represents Shin’s engagement with Korea’s traumatic present, “Mother and a Guest” (Sarangbang Sonnimgwa Eomeoni) finds him turning toward the quieter devastations of tradition. This is Shin in a more contemplative mode, adapting Joo Yo-seob’s beloved 1930s novel about a young widow (again Choi Eun-hee, luminous and restrained) whose moral strictures are challenged when a male boarder, Mr. Han, arrives at her household.

The film is narrated by the widow’s six-year-old daughter, Ok-hee, whose innocent perspective allows us to see the adult world with fresh eyes—much like Satyajit Ray’s “Pather Panchali” or, decades later, Yoon Ga-eun’s intimate character studies. What emerges is a portrait of a society at a crossroads, torn between Confucian ideals of female chastity and the modern recognition that widows, too, deserve happiness.

Choi Eun-hee’s performance is nothing short of remarkable. There’s a scene where she parades before a mirror wearing Mr. Han’s hat, briefly free from society’s gaze, allowing herself a moment of playful irreverence. It’s a small gesture, but it contains multitudes—all the desire and frustration of a woman trapped by propriety. This is classical Hollywood-style montage in service of deeply Korean concerns, and it’s executed with such delicate precision that the film has rightfully earned its status as one of the greatest Korean cinema classics.

The film ran into an interesting problem during production: Shin’s initial cut, faithful to the source material, barely exceeded an hour—too short for theatrical release. Rather than pad the runtime with filler, Shin added subplots and visual parallels that enriched the narrative tapestry. The result is a film that breathes, that allows its characters room to exist in contemplative spaces between dialogue.

The Collaborative Partnership: Shin and Choi

You cannot discuss Shin Sang-ok without discussing Choi Eun-hee. They married in 1954, and together they became Korean cinema’s golden couple—he behind the camera, she in front of it. Choi was already established as one of the “troika” of Korean actresses, alongside Kim Ji-mee and Um Aing-ran, but her collaborations with Shin elevated her to something more: the embodiment of Korean womanhood in transition.

In film after film—”A Romantic Papa” (1960), “Seong Chun-hyang” (1961), “Prince Yeonsan” (1961), “The Red Scarf” (1964)—Choi played women caught between tradition and modernity, between duty and desire. She had an extraordinary capacity for suggesting interior life through minimal expression, a skill that served Shin’s often elliptical storytelling perfectly.

“Mother and a Guest” earned her particular acclaim, cementing her association with the image of the Korean mother—self-sacrificing yet complex, traditional yet yearning. When the film won Best Picture at the 9th Asia Pacific Film Festival, it was as much a testament to Choi’s performance as to Shin’s direction.

The 1960s: Cinemascope and Color

Shin was always technically ambitious, never content to rest on his laurels. With “Seong Chun-hyang” (1961), he brought color cinemascope to Korean historical films for the first time. The adaptation of the classic pansori tale ran for 75 days in Seoul and drew approximately 400,000 viewers—an astonishing figure considering Seoul’s population was only 2.5 million at the time.

The success proved that Korean cinema could compete not just artistically but commercially. Shin later reflected on this moment, stating it gave him confidence that film could function as a genuine enterprise in Korea, not merely an art form but a viable industry. This conviction drove him to push boundaries further with “Prince Yeonsan” (1961), released in two parts, showcasing the spectacular potential of color and cinemascope in recreating historical palace scenes.

“The Red Scarf” (1964) represents another milestone—the first Korean film to employ aerial cinematography. Set during the Korean War and focusing on air force officers, it was a technical marvel that became a massive hit not just in Korea but throughout Southeast Asia. At the 11th Asia Pacific Film Festival, it earned awards for best director, editing, and acting. Taiwanese president Chiang Ching-kuo even personally requested that Shin make a similar film for Taiwan.

These weren’t vanity projects. Shin understood that spectacle serves narrative, that technical innovation could expand the vocabulary of Korean cinema. He was building a filmmaking tradition in real-time, proving that Korean directors could master any format, any genre.

The Decline: Political Interference and Personal Turmoil

But the 1970s brought a harsh reversal of fortune. South Korea’s cinema industry suffered under the increasingly repressive Park Chung-hee regime, which viewed film primarily as a propaganda tool. Strict censorship and constant government interference stifled creativity, and even Shin—who had thrived through sheer prolific output—found himself struggling.

The breaking point came in 1975 when Shin, characteristically fearless, announced his intention to film the Jeon Tae-il self-immolation incident—a defining moment in Korean labor history. The government was not amused. When Shin defiantly inserted Oh Soo-mi’s censored topless scene from “Rose and Wild Dog” into the film’s trailer, Park Chung-hee’s regime responded with fury. Shin Films’ license was revoked in 1978.

On a personal level, things were equally turbulent. Shin’s affair with actress Oh Soo-mi, which resulted in two children, became public in 1976, leading to divorce from Choi Eun-hee. It was a scandal that rocked Korean cinema—not just the dissolution of a marriage, but the symbolic end of an era.

Most of Shin’s films from this period were commercial failures. He traveled internationally, desperately seeking financing, trying to salvage his career. It was during one of these trips that the unthinkable happened.

The Kidnapping: Cinema’s Strangest Chapter

In January 1978, Choi Eun-hee traveled to Hong Kong, lured by promises of new business opportunities. She was kidnapped, drugged, and transported by speedboat to North Korea. Her captor was Kim Jong-il—not yet the Supreme Leader, but already obsessed with cinema and convinced that North Korean film needed international credibility.

Choi was housed in a luxury villa, toured Pyongyang, and attended films and operas with Kim Jong-il, who genuinely respected her artistic opinions. But she had been kidnapped, held against her will, subjected to ideological indoctrination. She wouldn’t learn for five years that she had been used as bait.

Six months later, in July 1978, Shin Sang-ok went to Hong Kong searching for his ex-wife. Despite their divorce, she remained his creative partner, his friend. What he found instead was a trap. North Korean agents kidnapped him too, chloroforming him and spiriting him away.

Unlike Choi, Shin’s initial treatment was harsh. After two failed escape attempts, he spent over two years in a prison camp, enduring “re-education” in North Korean ideology. It was a brutal experience designed to break his will and remake him as a loyal servant of the regime.

The Pyongyang Years: Forced Creativity

On March 7, 1983, Shin and Choi were reunited at a party hosted by Kim Jong-il. Neither had known the other was in North Korea. The reunion was emotional, surreal, orchestrated. Shortly afterward, at Kim’s suggestion, they remarried.

Kim Jong-il, it turned out, was a genuine cinephile. His personal film library contained over 15,000 films from around the world. He assigned Shin and Choi to watch and critique four films daily. While most were from Communist bloc countries, Hollywood films occasionally appeared. Kim wanted to understand why Western cinema succeeded where North Korean propaganda failed.

In an extraordinary act of foresight, Choi and Shin began secretly recording their conversations with Kim, understanding they would need proof of their coercion if they ever escaped. In one recording from October 1983, Kim speaks candidly about orchestrating their kidnappings to improve North Korean cinema. These tapes, later made public, provided irrefutable evidence of their captivity.

Between 1983 and 1986, Shin directed seven films for Kim Jong-il, who functioned as executive producer: “An Emissary of No Return,” “Runaway,” “Love, Love, My Love,” “Salt,” “The Tale of Shim Chong,” “Breakwater,” and the cult classic “Pulgasari.” Kim gave Shin unprecedented creative freedom by North Korean standards, hoping to create films that would impress international audiences.

“Salt” won Choi Eun-hee the Best Actress award at the 14th Moscow International Film Festival, while “An Emissary of No Return” and “Salt” received recognition at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. These weren’t typical propaganda films—they contained actual artistic merit, made by a master working under impossible conditions.

“Pulgasari” (1985) has since achieved cult status. A giant-monster film clearly modeled on Godzilla, it tells the story of a metal-eating creature born from a figurine and rice fed by a blacksmith’s daughter. The monster grows enormous, eventually helping peasants overthrow a tyrannical king. The film featured Japanese special effects technicians and represented North Korea’s bizarre attempt at creating its own kaiju cinema.

There’s something deeply melancholic about watching “Pulgasari” today. Here’s Shin Sang-ok, who once commanded the heights of Korean cinema, reduced to directing a socialist Godzilla knockoff for a dictator. Yet even in captivity, his craftmanship shines through. The film is technically competent, occasionally imaginative, and carries subtle undercurrents of resistance—the tyrannical king bears uncomfortable resemblance to Kim’s regime.

The Vienna Escape

In 1986, Kim Jong-il sent Shin and Choi to Vienna to meet with potential financiers for a biographical film about Genghis Khan. It was the opening they had been waiting for eight years to find.

In Vienna, they managed to slip away from their North Korean handlers and reach the U.S. embassy, where they requested political asylum. Kim Jong-il, in a bizarre reversal, became convinced that the Americans had kidnapped them. North Korea’s official response was to claim that Shin and Choi had willingly defected to the North and had embezzled money intended for the Genghis Khan film—a transparent lie that fooled no one.

The couple lived covertly in Reston, Virginia, for two years under American protection, debriefing CIA agents about Kim Jong-il and their experiences. In 1989, they became American citizens, adopting the names Simon Sheen and Theresa Sheen.

The American Years and Return

Working as Simon S. Sheen in Los Angeles during the 1990s, Shin found himself directing films like “3 Ninjas Knuckle Up” and working as executive producer on “3 Ninjas Kick Back” and “3 Ninjas: High Noon at Mega Mountain.” These were children’s martial arts films—competent, professional, but a far cry from “A Flower in Hell” or “Mother and a Guest.”

There’s something profoundly sad about this chapter. Here was one of Asia’s greatest directors, reduced to journeyman work on franchise children’s films. Yet Shin never complained publicly. He was a professional, and he understood that in Hollywood, you took the work you could get.

In 1994, he returned to South Korea permanently, still fearful that security services might not believe his kidnapping story. That same year, he was invited to serve as a jury member at the Cannes Film Festival—a recognition of his contributions to world cinema. He continued making films in Korea, though none reached the heights of his 1960s masterworks.

Legacy and Recognition

Shin Sang-ok passed away on April 11, 2006, at age 80 (or 79, depending on conflicting birth records). He was posthumously awarded the Gold Crown Cultural Medal by President Roh Moo-hyun—South Korea’s highest honor for an artist.

In 2015, Paul Fischer published “A Kim Jong-Il Production: The Extraordinary True Story of a Kidnapped Filmmaker,” bringing Shin’s bizarre ordeal to international attention. In 2016, the documentary “The Lovers and the Despot,” directed by Robert Cannan and Ross Adam, premiered at Sundance, featuring archival footage and interviews with Choi Eun-hee, who lived until 2018.

The BBC Radio 4 drama “Lights, Camera, Kidnap!” (2017) dramatized their story, ensuring that this strangest chapter of cinema history would not be forgotten.

Retrospectives and Restoration

In recent years, film festivals have recognized Shin’s contributions with major retrospectives. The 2017 Nantes Three Continents Film Festival featured a program titled “SHIN Sang-ok, The Korean Equation,” showcasing fourteen of his films. The San Sebastián International Film Festival has included his works in explorations of Korean cinema’s golden age.

The Korean Film Archive, with support from Naver, has been systematically restoring Shin’s films, making them available on YouTube and Blu-ray. This preservation work is crucial—many Korean films from this period have been lost to neglect and deterioration. Each restoration is an archaeological recovery, rescuing another piece of cinema history from oblivion.

Reflections on a Cinema Prince

What strikes me most about Shin Sang-ok, having spent years exploring his filmography, is his sheer versatility. He could make intimate melodramas like “Mother and a Guest” and epic historical spectacles like “Prince Yeonsan.” He could craft gritty social commentary in “A Flower in Hell” and broad comedy in “A Romantic Papa.” He worked in every genre, mastered every format available to him.

But more than technical skill, Shin possessed something rarer: a genuine understanding of Korean society in flux. His films capture a nation rebuilding itself, negotiating between tradition and modernity, between East and West. The women in his films—especially those played by Choi Eun-hee—embody these tensions with extraordinary complexity. They’re not symbols but fully realized human beings, struggling with real constraints and genuine desires.

The kidnapping story, while extraordinary, shouldn’t overshadow his artistic achievements. Yes, it’s the kind of plot twist that makes his biography read like fiction. But the real story is in the films themselves—74 of them, spanning five decades, charting the evolution of Korean cinema from post-colonial infancy to international recognition.

When film historians write about Korean cinema’s golden age, they inevitably return to Shin Sang-ok. He didn’t just participate in that golden age; he created it, frame by frame, film by film. He built the infrastructure, trained the talent, proved that Korean cinema could compete globally. Every Korean filmmaker who followed—from Im Kwon-taek to Park Chan-wook to Bong Joon-ho—walks paths that Shin first cut.

The Prince’s Kingdom

“The Prince of South Korean Cinema”—the title was well-earned. Like any prince, Shin understood that building a kingdom required more than just personal brilliance. It required vision, infrastructure, and the willingness to take risks that others deemed foolish.

When I watch “A Flower in Hell” today, I’m struck by how contemporary it feels. The moral ambiguity, the unflinching gaze at poverty and survival, the refusal to offer easy answers—these are the hallmarks of great cinema, regardless of era. The same holds true for “Mother and a Guest,” with its quiet exploration of female desire constrained by social expectation.

These films aren’t museum pieces. They’re living works that continue to speak to audiences willing to listen. They remind us that Korean cinema’s current international prominence didn’t emerge from nowhere—it has deep roots, planted by filmmakers like Shin Sang-ok who believed that Korean stories, told with Korean voices, deserved a global audience.

The tragedy of Shin’s career—the political persecution, the kidnapping, the forced exile—shouldn’t define him. What should define him is the sheer volume and quality of work he produced under conditions ranging from post-war poverty to dictatorial censorship to literal captivity. He kept making films because that’s what he was: a filmmaker, in the purest sense.

In the end, Shin Sang-ok’s greatest legacy isn’t any single film, remarkable as many of them are. It’s the model he provided of what Korean cinema could be: ambitious, technically sophisticated, artistically serious, commercially viable, and unmistakably Korean. He showed a generation of filmmakers that they didn’t have to choose between art and entertainment, between Korean tradition and international appeal.

The Prince of South Korean Cinema reigned over a golden age of remarkable creativity, and his kingdom—Korean cinema itself—continues to thrive, built on foundations he laid seven decades ago. That’s a legacy worth celebrating, worth preserving, worth revisiting in darkened theaters where his films still flicker to life, as vital and necessary as the day they were made.

For cinephiles exploring Korean cinema’s rich history, Shin Sang-ok remains essential viewing—not as a curiosity or historical footnote, but as a master craftsman whose best work stands alongside the greatest achievements of world cinema. The Prince may have departed, but his kingdom endures.