The cinematic landscape of the 1960s and 1970s witnessed a seismic shift in West Germany, a cultural and artistic eruption that would come to be known as the “New German Cinema” (Neuer Deutscher Film). More than just a collection of films, it was a movement, a rebellion against the stagnant and commercially driven filmmaking of the post-war era. It was a generation of young, fiercely independent filmmakers who, armed with little more than a burning desire to confront their nation’s unassimilated past, critique its present, and forge a new cinematic language, irrevocably altered the course of German and international cinema.

Emerging from the ashes of World War II and the subsequent economic phenomenon (Wirtschaftswunder), West German society grappled with a collective amnesia, a reluctance to confront the horrors of the Nazi regime and its lingering shadows.

The mainstream cinema of the time often offered escapist entertainment, saccharine Heimatfilme (homeland films) that romanticized an idealized past and glossed over the complexities of national identity. It was against this backdrop of artistic and societal complacency that the New German Cinema defiantly announced its arrival.

The seeds of this cinematic revolution were sown on February 28, 1962, at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival. A group of 26 young filmmakers, including Alexander Kluge, Edgar Reitz, Peter Schamoni, and Haro Senft, issued a bold manifesto. “The old cinema is dead,” it declared. “We believe in the new cinema.” This Oberhausen Manifesto was a galvanizing call to arms, rejecting the commercialism and artistic stagnation of the established film industry and demanding a cinema that was intellectually rigorous, socially relevant, and artistically innovative. They envisioned a cinema that would engage with the complexities of German history and contemporary society, a cinema that would be auteur-driven, with the director as the central creative force.

The Oberhausen Manifesto, though symbolic, laid the groundwork for the movement. It articulated the frustrations of a generation yearning for a cinema that reflected their experiences and concerns. These young filmmakers, many of whom had been children during the war, felt a profound disconnect from the narratives being presented on screen. They sought to excavate the buried truths of the past, to understand the silence surrounding the Nazi era, and to critically examine the burgeoning consumer culture and political landscape of West Germany.

The initial years following the Oberhausen Manifesto were characterized by struggle and limited resources. The established film industry largely ignored the demands of the young filmmakers. However, the spirit of the manifesto and the growing international recognition of some early works began to garner attention. Crucially, in 1965, the Kuratorium Junger Deutscher Film (Young German Film Board) was established. Funded by the federal states, this institution provided crucial financial support for first-time filmmakers, operating on a loan basis. This marked a significant turning point, providing the nascent movement with the means to produce their unconventional and often politically charged films.

The late 1960s and the 1970s witnessed the true flourishing of the New German Cinema. A diverse array of directorial voices emerged, each with their unique style and thematic concerns, yet united by a shared commitment to artistic integrity and social critique. This period saw the rise of filmmakers who would become internationally renowned, leaving an indelible mark on cinematic history.

Key Figures and Their Contributions:

- Alexander Kluge: Often considered the intellectual father figure of the New German Cinema, Kluge’s work was characterized by its experimental narrative structures, essayistic style, and rigorous engagement with history, politics, and the role of media. His films, such as “Yesterday Girl” (1966) and “Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed” (1968), challenged conventional storytelling, employing montage, intertitles, documentary footage, and philosophical voiceovers to provoke critical reflection. Kluge’s background in law and his association with the Frankfurt School’s critical theory deeply influenced his cinematic approach. He saw cinema as a tool for intellectual inquiry and social commentary, dissecting the complexities of German identity and the mechanisms of power.

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder: A prolific and controversial figure, Fassbinder was a force of nature within the New German Cinema. In his short but intensely creative life, he directed over 40 films, television series, and theatrical productions. His work was characterized by its raw emotional intensity, theatrical stylization, and unflinching exploration of marginalized individuals and societal power structures. Fassbinder’s films often focused on themes of alienation, oppression, and the corrosive effects of capitalism on human relationships. From the melodrama of “Ali: Fear Eats the Soul” (1974), which explored the prejudice faced by an older German woman who marries a younger Moroccan guest worker, to the epic historical sweep of “Berlin Alexanderplatz” (1980), a 14-part television adaptation of Alfred Döblin’s novel, Fassbinder’s work was both deeply personal and fiercely political. He drew inspiration from Hollywood melodramas but subverted their conventions to expose the underlying social and psychological tensions. His confrontational style and exploration of taboo subjects often sparked controversy, but his impact on cinema as a medium for social and emotional excavation remains undeniable.

- Werner Herzog: A visionary and often eccentric filmmaker, Herzog is known for his adventurous and often perilous productions, his fascination with extreme landscapes and the human condition under duress, and his unique blend of documentary and fiction filmmaking. Films like “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” (1972) and “Fitzcarraldo” (1982), both starring the volatile Klaus Kinski, are testaments to Herzog’s relentless pursuit of his artistic vision, often pushing the boundaries of filmmaking and the physical and mental endurance of his cast and crew. His documentaries, such as “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser” (1974) and “Grizzly Man” (2005), explore themes of isolation, madness, and the complex relationship between humanity and nature. Herzog’s films are characterized by their poetic imagery, philosophical depth, and a sense of awe and wonder at the strangeness of existence.

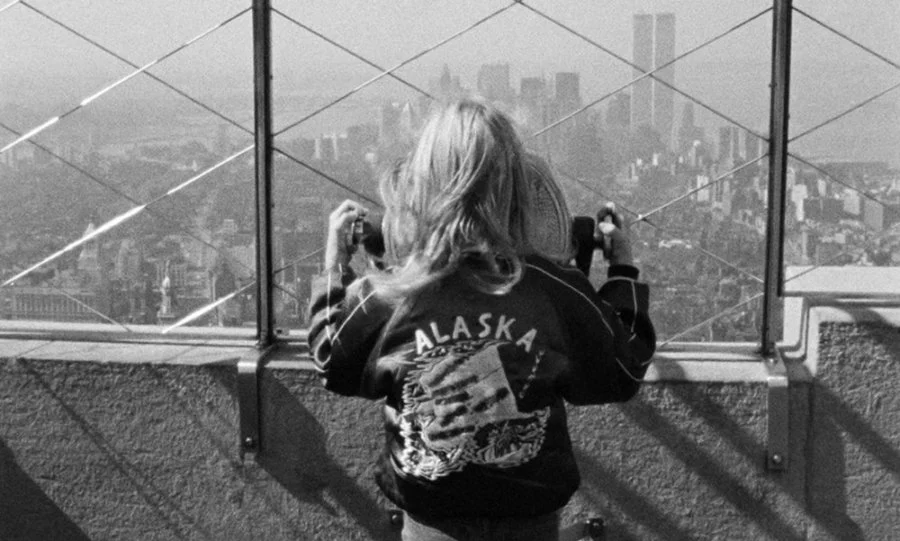

- Wim Wenders: A more introspective and melancholic voice within the movement, Wenders explored themes of alienation, identity, and the search for meaning in a fragmented modern world. His early road movies, such as “Alice in the Cities” (1974) and “Kings of the Road” (1976), captured a sense of post-war displacement and the search for connection across a changing landscape. Wenders’s work often engaged with American popular culture, particularly music and cinema, reflecting a complex relationship between Germany and the United States. His later international successes, such as “Paris, Texas” (1984) and “Wings of Desire” (1987), further cemented his reputation as a filmmaker with a unique visual style and a deep understanding of human emotions.

- Margarethe von Trotta: A crucial female voice within the New German Cinema, von Trotta’s work often focused on the experiences of women in a patriarchal society, exploring themes of sisterhood, political activism, and the personal consequences of political ideologies. Her films, such as “The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum” (1975), co-directed with Volker Schlöndorff, which examined the media’s destructive power, and “Marianne and Juliane” (1981), which explored the divergent paths of two sisters involved in the radical left, offered important feminist perspectives within the movement. Von Trotta’s work challenged traditional gender roles and provided nuanced portrayals of women’s struggles and resilience.

- Volker Schlöndorff: Known for his literary adaptations and his engagement with historical and political themes, Schlöndorff’s work often bridged the gap between art-house cinema and a wider audience. His adaptation of Günter Grass’s “The Tin Drum” (1979) achieved international acclaim and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, bringing the New German Cinema to a global audience. Schlöndorff’s films often combined historical context with personal narratives, exploring the impact of larger political forces on individual lives.

Common Themes and Stylistic Characteristics:

While the individual filmmakers of the New German Cinema possessed distinct artistic visions, their work collectively engaged with several recurring themes and often shared certain stylistic characteristics:

- Confronting the Past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung): A central concern of the movement was the need to come to terms with Germany’s Nazi past. Filmmakers directly or indirectly addressed the silence and denial surrounding this period, exploring its lingering effects on contemporary society. Films like Fassbinder’s “The Marriage of Maria Braun” (1979), which allegorically used the story of a woman’s survival in post-war Germany to reflect the nation’s economic recovery and moral ambiguities, and Edgar Reitz’s later epic “Heimat” cycle (1984-2013), which meticulously chronicled the lives of ordinary people in a small German village across decades, exemplified this engagement with history.

- Critique of Contemporary Society: The New German Cinema was deeply critical of the consumerism, political conservatism, and social inequalities of post-war West Germany. Films often depicted alienation, the emptiness of material success, and the struggles of marginalized groups. Fassbinder’s searing social critiques, for instance, often exposed the hypocrisy and brutality underlying seemingly normal bourgeois life.

- The Auteur as Central Creative Force: Inspired by the French New Wave, the New German Cinema championed the director as the primary artistic visionary, responsible for all aspects of the film’s creation. This emphasis on the auteur led to highly personal and stylistically distinctive works.

- Experimentation with Narrative and Form: Rejecting the conventions of traditional storytelling, many New German Cinema filmmakers experimented with fragmented narratives, non-linear timelines, unconventional editing techniques, and the blurring of genres. Kluge’s essayistic films, Herzog’s blend of documentary and fiction, and Fassbinder’s theatrical stylization all demonstrated this commitment to formal innovation.

- Low-Budget Productions and Independent Spirit: Often working with limited financial resources, the filmmakers of the New German Cinema embraced an independent spirit, often challenging the established production and distribution systems. The initial support from the Kuratorium Junger Deutscher Film was crucial in enabling these low-budget but artistically ambitious projects.

- Political Engagement: Many filmmakers were deeply engaged with the social and political movements of the 1960s and 1970s, including student protests, the rise of feminism, and debates about Germany’s role in the world. Their films often reflected these concerns, addressing issues of political radicalism, social justice, and the complexities of national identity in a divided Germany.

- Influence of International Cinema: The New German Cinema was influenced by international movements like Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave, adopting their spirit of social realism and formal experimentation while forging its own distinct aesthetic and thematic concerns.

The Fragmentation and Legacy of the Movement:

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the cohesive energy of the New German Cinema began to wane. Several factors contributed to this shift. The initial sense of collective purpose that had united the filmmakers began to dissipate as individual careers and artistic visions diverged. Some directors, like Wenders and Schlöndorff, achieved greater international success and moved towards larger-budget productions, sometimes with American studio involvement. Others, like Fassbinder, remained fiercely independent but faced increasing critical backlash and financial difficulties.

Furthermore, the political and cultural landscape of West Germany was changing. The radicalism of the 1960s and 1970s gave way to a more conservative climate in the 1980s. Funding structures for independent filmmaking also evolved, and the initial impetus for a unified “new cinema” gradually faded.

However, the impact and legacy of the New German Cinema are profound and enduring. It revitalized German cinema, bringing it back to international prominence for the first time since the Weimar era. It fostered a generation of fiercely original and intellectually engaged filmmakers who challenged conventions and tackled complex social and historical issues. Their innovative approaches to narrative, form, and thematic content influenced filmmakers around the world.

The New German Cinema also played a crucial role in Germany’s coming to terms with its past. By directly addressing the silences and evasions surrounding the Nazi era, these filmmakers contributed to a more critical and nuanced understanding of national identity. Their work sparked public debate and encouraged a deeper engagement with the complexities of German history.

Moreover, the movement paved the way for future generations of German filmmakers, demonstrating that artistic integrity and social relevance could coexist. The spirit of independence and the commitment to auteur filmmaking fostered during the New German Cinema continue to resonate in contemporary German cinema.

In conclusion, the New German Cinema was more than just a cinematic trend; it was a cultural and artistic phenomenon that reflected a nation grappling with its past and seeking to define its future. The audacious voices of Kluge, Fassbinder, Herzog, Wenders, von Trotta, Schlöndorff, and their contemporaries created a body of work that was challenging, provocative, and ultimately transformative. Their films remain a vital testament to the power of cinema to engage with history, critique society, and push the boundaries of artistic expression, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of world cinema. The “new cinema” they envisioned became a reality, and its echoes continue to resonate in the films of today.

The exploration of the New German Cinema extends beyond the major figures, encompassing a wider array of talent and diverse perspectives that contributed to the richness and complexity of the movement. While the aforementioned directors often receive the most attention, acknowledging the contributions of others provides a more complete picture of this pivotal era in German film history.

Expanding the Landscape: Other Notable Filmmakers:

- Edgar Reitz: While perhaps best known for his monumental “Heimat” cycle, Reitz was a signatory of the Oberhausen Manifesto and a significant figure in the early years of the New German Cinema. His first feature film, “Mahlzeiten” (1967), explored themes of alienation and the breakdown of relationships in post-war Germany, aligning with the movement’s critical examination of contemporary society. Reitz’s later work, particularly the “Heimat” films, though produced later, can be seen as a continuation of the New German Cinema’s commitment to exploring German history and identity through personal narratives.

- Hans-Jürgen Syberberg: An often controversial and highly individualistic filmmaker, Syberberg’s work was characterized by its theatricality, historical allegories, and experimental use of puppets and backdrops. His epic films, such as “Ludwig II: Requiem for a Virgin King” (1972) and the seven-hour “Hitler: A Film from Germany” (1977), offered highly stylized and often unsettling meditations on German history, mythology, and the rise of fascism. Syberberg’s unique and often challenging aesthetic placed him somewhat outside the mainstream of the New German Cinema, but his ambitious projects and willingness to confront difficult historical subjects aligned with the movement’s broader aims.

- Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet: This radical filmmaking duo, working collaboratively, developed a highly rigorous and intellectually demanding cinematic style. Their films, often adaptations of literary or operatic works, were characterized by their long takes, minimalist staging, and emphasis on the materiality of film itself. Works like “Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach” (1968) and “Moses and Aaron” (1975) challenged conventional narrative and audience expectations, demanding an active and critical engagement from the viewer. Their uncompromising artistic vision and rejection of commercial cinema positioned them as important, albeit often marginalized, figures within the New German Cinema landscape.

- Helma Sanders-Brahms: Another significant female voice, Sanders-Brahms’s films often explored the experiences of women in post-war Germany, blending personal narratives with broader social and political contexts. Films like “Germany, Pale Mother” (1980), a semi-autobiographical account of a woman’s life during and after the war, offered a powerful and often overlooked perspective on German history and the impact of conflict on individual lives. Her work contributed to the feminist interventions within the New German Cinema, highlighting women’s perspectives and challenging patriarchal structures.

- Ulrike Ottinger: Known for her visually flamboyant and often surreal films, Ottinger explored themes of gender, sexuality, and cultural difference. Her work often featured strong female characters and challenged conventional notions of identity and representation. Films like “Madame X: An Absolute Ruler” (1977) and “Ticket of No Return” (1979) were characterized by their bold aesthetic, theatricality, and exploration of marginalized communities. Ottinger’s unique visual style and subversive themes added another layer of complexity to the New German Cinema.

The Role of Television:

Television played a complex and often crucial role in the development and dissemination of the New German Cinema. While the movement initially positioned itself in opposition to the perceived commercialism of television, the medium eventually became an important source of funding and a platform for reaching a wider audience.

Filmmakers like Fassbinder, with his epic television series “Berlin Alexanderplatz,” and Reitz, with his sprawling “Heimat” cycle, utilized the extended format of television to explore their themes in greater depth. Television co-productions became increasingly common, providing much-needed financial support for ambitious projects that struggled to find funding within the traditional film industry.

However, this relationship was not without its tensions. Filmmakers often had to negotiate creative control and content with television broadcasters, leading to compromises and sometimes conflicts. Nevertheless, television undeniably broadened the reach of the New German Cinema, bringing its often challenging and unconventional narratives into the living rooms of German viewers.

The Influence of Literature and Intellectual Thought:

The New German Cinema was deeply intertwined with contemporary German literature and intellectual discourse. Many filmmakers adapted works by prominent German authors, such as Heinrich Böll (Schlöndorff’s “The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum”) and Günter Grass (Schlöndorff’s “The Tin Drum”). These adaptations brought important literary voices and social critiques to a wider audience.

Furthermore, the movement was informed by critical theory, particularly the Frankfurt School’s analysis of power, ideology, and the role of media in shaping society. Filmmakers like Kluge explicitly engaged with these ideas in their work, using cinema as a tool for critical inquiry and social commentary. This intellectual grounding distinguished the New German Cinema from more purely entertainment-driven filmmaking.

International Reception and Influence:

Despite often struggling at the domestic box office, the New German Cinema gained significant international recognition and critical acclaim. Films by Fassbinder, Herzog, Wenders, and Schlöndorff were celebrated at international film festivals, earning awards and attracting a dedicated following among cinephiles and critics worldwide.

The movement’s innovative filmmaking techniques, its willingness to confront difficult historical and social issues, and the unique visions of its key auteurs had a profound influence on subsequent generations of filmmakers internationally. The emphasis on the director as the central creative force, the exploration of complex themes, and the experimentation with narrative and form resonated with filmmakers seeking to push the boundaries of cinematic expression.

The New German Cinema also contributed to a broader understanding of post-war Germany beyond its economic success, offering nuanced and often critical perspectives on its history, culture, and society. It challenged simplistic narratives and fostered a more complex understanding of German identity.

The Enduring Relevance:

While the period formally recognized as the New German Cinema may have concluded in the early 1980s, its spirit and influence continue to be felt in contemporary German filmmaking. The emphasis on auteur filmmaking, the willingness to engage with social and political issues, and the commitment to artistic innovation remain important aspects of German cinematic culture.

Furthermore, the themes explored by the New German Cinema – the burden of history, the complexities of national identity, the critique of social inequalities, and the search for individual meaning in a modern world – remain relevant in Germany and beyond. The films of this era offer valuable insights into the challenges and transformations of post-war Europe and continue to spark dialogue and reflection.

In conclusion, the New German Cinema was a multifaceted and dynamic movement that encompassed a diverse range of voices and artistic visions. Beyond the well-known figures, the contributions of filmmakers like Reitz, Syberberg, Straub and Huillet, Sanders-Brahms, and Ottinger, along with the complex relationship with television and the strong intellectual and literary underpinnings of the movement, paint a richer and more nuanced picture of this pivotal era in cinematic history. The international recognition and enduring influence of the New German Cinema solidify its place as a transformative force in the world of film. The legacy of its audacious spirit and commitment to a meaningful and innovative cinema continues to inspire and challenge filmmakers and audiences alike. Sources and related content