The French New Wave, or La Nouvelle Vague, stands as one of the most influential movements in the history of cinema. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing through the 1960s, this revolutionary wave of filmmaking broke away from the conventions of traditional cinema, redefining storytelling, aesthetics, and the role of the filmmaker. Spearheaded by a group of young critics-turned-directors—most notably François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, Claude Chabrol, and Éric Rohmer—the French New Wave challenged the rigid structures of the French film industry and inspired a global rethinking of what cinema could be. Its impact resonates today, influencing modern filmmakers, shaping cinematographic techniques, and leaving an indelible mark on the art form.

This article delves into every aspect of the French New Wave: its historical context, defining characteristics, key contributors, thematic preoccupations, and innovative techniques. Most importantly, it examines how this movement continues to influence contemporary cinema, from indie auteurs to Hollywood blockbusters.

Historical Context: The Seeds of Rebellion

The French New Wave did not emerge in a vacuum. Post-World War II France was a nation in flux, grappling with reconstruction, shifting cultural values, and a burgeoning youth culture. The French film industry of the 1940s and 1950s, often referred to as the “Tradition of Quality,” was dominated by lavish literary adaptations, studio-bound productions, and a polished, predictable aesthetic. These films, while technically proficient, were seen by many as formulaic and disconnected from the realities of modern life.

Enter the Cahiers du Cinéma, a film journal founded in 1951 by André Bazin, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, and others. This publication became the intellectual breeding ground for the New Wave. Young critics like Truffaut, Godard, and their peers used Cahiers as a platform to critique the staid French cinema of their time while championing directors they admired—both French (Jean Renoir, Robert Bresson) and international (Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks). They argued for the auteur theory, a concept popularized by Truffaut in his 1954 essay “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” which posited that a film’s director should be its primary creative force, imprinting a personal vision onto the work.

The late 1950s provided fertile ground for this rebellion. Technological advancements, such as lightweight cameras (e.g., the Éclair Cameflex) and portable sound equipment, made filmmaking more accessible. Meanwhile, a restless postwar generation sought art that reflected their experiences—alienation, freedom, and existential uncertainty. The French New Wave was born from this convergence of ideas, technology, and cultural upheaval.

Defining Characteristics: Breaking the Mold

The French New Wave was less a cohesive movement with a manifesto than a shared ethos among filmmakers. Its hallmarks included experimentation, spontaneity, and a rejection of cinematic norms. Here are its defining traits:

- Low-Budget, Independent Production: New Wave directors often worked outside the traditional studio system, using minimal crews, borrowed equipment, and real locations instead of sets. This DIY approach gave their films a raw, unpolished energy.

- Improvisation and Spontaneity: Scripts were often loose or incomplete, with dialogue improvised on set. Jean-Luc Godard famously wrote scenes for Breathless (1960) the morning of shooting, embracing a chaotic, in-the-moment creative process.

- Cinematic Self-Reflexivity: New Wave films frequently acknowledged their own artifice, breaking the fourth wall or referencing other movies. This meta-awareness invited audiences to engage with cinema as an art form rather than a passive escape.

- Innovative Editing: Discontinuity editing—jump cuts, abrupt transitions, and non-linear narratives—became a signature of the movement. These techniques disrupted traditional storytelling, reflecting the fragmented nature of modern life.

- Youthful Energy and Modernity: The films often centered on young protagonists navigating love, rebellion, and existential crises, set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing France.

- Personal Vision: True to the auteur ethos, each director infused their work with a distinct style and worldview, making every film a personal statement.

Key Figures: The Architects of the New Wave

The French New Wave was driven by a cadre of visionary filmmakers, each bringing unique perspectives to the movement. Below are the most prominent figures and their contributions:

- François Truffaut: Often seen as the movement’s heart, Truffaut debuted with The 400 Blows (1959), a semi-autobiographical tale of a troubled youth, Antoine Doinel. The film’s naturalistic performances, handheld camerawork, and emotional depth won the Best Director prize at Cannes and established Truffaut as a major talent. His later works, like Jules and Jim (1962), blended romanticism with formal experimentation.

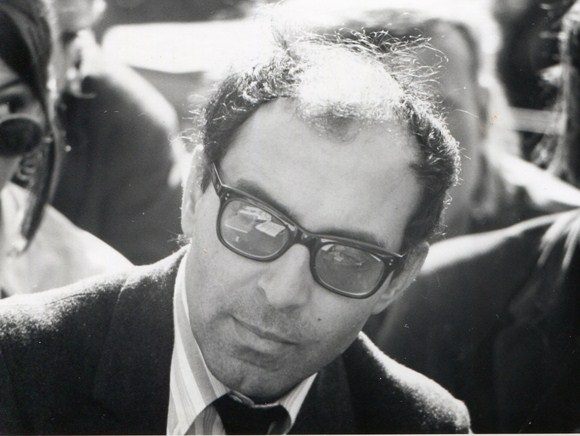

- Jean-Luc Godard: The movement’s radical provocateur, Godard redefined cinema with Breathless (1960), a stylish crime drama starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg. Known for its jump cuts, philosophical tangents, and pop culture references, the film epitomized the New Wave’s rule-breaking spirit. Godard’s prolific output—Pierrot le Fou (1965), Week-end (1967)—pushed boundaries further into political and avant-garde territory.

- Agnès Varda: Dubbed the “grandmother of the New Wave,” Varda brought a feminist and poetic sensibility to the movement. Her debut, La Pointe Courte (1955), predated the New Wave but foreshadowed its style, blending documentary and fiction. Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), a real-time portrait of a singer awaiting a medical diagnosis, showcased her lyrical approach to time and identity.

- Claude Chabrol: Often called the “French Hitchcock,” Chabrol explored psychological tension and bourgeois hypocrisy. Films like Les Cousins (1959) and Le Beau Serge (1958)—sometimes considered the first New Wave film—combined suspense with social critique.

- Éric Rohmer: Known for his cerebral, dialogue-driven films, Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s (1969) and the Six Moral Tales series emphasized moral dilemmas and human relationships over flashy visuals.

Other notable contributors included Jacques Rivette (Paris Belongs to Us, 1961), Alain Resnais (Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1959), and Louis Malle (Elevator to the Gallows, 1958), whose works intersected with New Wave ideals while retaining distinct identities.

Thematic Preoccupations: The Soul of the New Wave

The French New Wave was as much about ideas as it was about style. Its films grappled with themes that resonated with a generation coming of age in a postwar world:

- Existentialism: Influenced by philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, New Wave characters often faced existential crises, questioning meaning in a chaotic universe. Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie (1962), starring Anna Karina as a woman drifting into prostitution, exemplifies this introspective despair.

- Youth and Rebellion: The movement captured the restlessness of the late 1950s and 1960s youth culture. Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel became an icon of youthful defiance, while Godard’s anarchic protagonists flouted societal norms.

- Love and Relationships: Romantic entanglements were a recurring motif, often portrayed with a mix of tenderness and cynicism. Jules and Jim’s tragic love triangle and Breathless’s fleeting romance reflect the complexity of human connection.

- Modernity and Urban Life: Paris, with its bustling streets and cafes, was a central character in many films. The New Wave embraced the city’s vibrancy while critiquing its alienation and consumerism.

- Cinema Itself: The movement’s self-referential nature—homages to Hollywood, nods to silent films, and playful deconstructions—celebrated cinema as an evolving art form.

Stylistic Innovations: A New Visual Language

The French New Wave’s technical innovations were as groundbreaking as its themes. These techniques not only defined the movement but also reshaped cinematic grammar:

- Handheld Cinematography: Lightweight cameras allowed directors to shoot on location with fluid, dynamic movements. Raoul Coutard, Godard’s frequent cinematographer, pioneered this approach, giving films an intimate, documentary-like feel.

- Jump Cuts: Godard’s use of jump cuts in Breathless—abrupt edits within a single scene—shattered continuity, creating a jarring, modernist rhythm that mirrored the characters’ disjointed lives.

- Natural Lighting: Eschewing artificial studio lights, New Wave filmmakers embraced available light, enhancing realism. This technique was both practical (due to budget constraints) and aesthetic, grounding films in everyday environments.

- Long Takes and Real Time: Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7 unfolded in real time, while Rivette’s lengthy, unhurried scenes emphasized duration and contemplation.

- Sound Design: Direct sound recording, often imperfect and ambient, replaced polished studio dubbing. Asynchronous sound—where audio and visuals didn’t align—added to the experimental texture.

These innovations weren’t mere gimmicks; they reflected the movement’s ethos of freedom and authenticity, prioritizing artistic expression over technical perfection.

Impact on Modern Cinematography and Filmmakers

The French New Wave’s influence extends far beyond its 1960s heyday, permeating contemporary cinema across genres, budgets, and national boundaries. Its legacy can be seen in several key areas:

- The Rise of the Auteur: The auteur theory became a cornerstone of film studies and practice. Modern directors like Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, and Sofia Coppola embody this ideal, crafting films that bear their unmistakable signatures. Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994), with its non-linear structure and pop culture references, owes a clear debt to Godard.

- Independent Cinema: The New Wave’s low-budget, DIY ethos inspired the indie film boom of the 1990s and beyond. Directors like Richard Linklater (Slacker, 1990) and the Safdie Brothers (Uncut Gems, 2019) echo its emphasis on raw energy, improvisation, and real-world settings.

- Stylistic Experimentation: Jump cuts, handheld shots, and self-reflexivity are now staples of modern filmmaking. Music videos, commercials, and even blockbusters like Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) use rapid editing and dynamic camera work pioneered by the New Wave.

- Narrative Freedom: The movement’s rejection of linear storytelling paved the way for fragmented narratives in films like Memento (2000) by Christopher Nolan and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) by Michel Gondry, a French filmmaker whose whimsical style nods to Varda.

- Global Influence: The New Wave sparked parallel movements worldwide—Italy’s Neorealism evolved into more personal works, Japan’s New Wave (e.g., Nagisa Oshima), and America’s New Hollywood (Scorsese, Coppola). Today, filmmakers like Bong Joon-ho (Parasite, 2019) blend genre with auteurist flair, a testament to the movement’s global reach.

- Female Filmmakers: Agnès Varda’s trailblazing role opened doors for women in cinema. Directors like Greta Gerwig (Lady Bird, 2017) and Céline Sciamma (Portrait of a Lady on Fire, 2019) carry forward her legacy of intimate, female-centered storytelling.

- Cinematic Homage: Modern films often pay direct tribute to the New Wave. Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016) echoes The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) by Jacques Demy, while Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (2016) channels Rohmer’s quiet introspection.

Case Studies: New Wave in Modern Films

To illustrate the movement’s impact, consider these examples:

- Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction: The film’s playful dialogue, eclectic soundtrack, and fractured timeline recall Godard’s Breathless. Tarantino has cited the New Wave as a major influence, particularly its blend of high and low culture.

- Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003): Coppola’s use of urban alienation, natural lighting, and existential melancholy mirrors Truffaut and Varda, while her status as an auteur aligns with the movement’s ideals.

- Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express (1994): This Hong Kong masterpiece adopts the New Wave’s handheld camerawork, vibrant cityscapes, and romantic ambiguity, showing the movement’s transcultural resonance.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy

The French New Wave was more than a fleeting moment in film history; it was a seismic shift that redefined cinema as an art form. Its rejection of convention, embrace of experimentation, and celebration of the director’s voice liberated filmmakers from the constraints of tradition. Today, its influence is everywhere—from the gritty realism of indie cinema to the bold stylization of mainstream hits. As long as filmmakers seek to innovate and express personal truths, the spirit of La Nouvelle Vague will endure, proving that a small group of rebels with cameras can change the world of cinema forever.

Pingback: Jean-Luc Godard: Revolutionary Cinema and the New Wave Legacy - deepkino.com

Pingback: Claude Chabrol: Master of the French New Wave and Psychological Cinema - deepkino.com

Nice slot bro!

Pingback: Beyond the Camera: Unpacking the Director as Film’s True Author or “Auteur Theory” - deepkino.com