Introduction

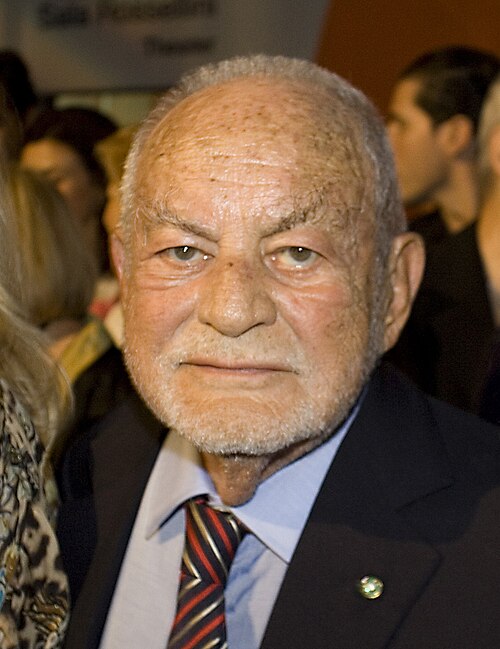

In the entire history of film, few can claim a career as wide, varied, and influential as that of Dino De Laurentiis. Born Agostino De Laurentiis on August 8, 1919 in Torre Annunziata, near Naples, he emerged from humble roots—helping sell his father’s pasta as a teenager—before staking his claim in the cinematic world. Over a career spanning nearly seven decades, he produced or co-produced more than 500 films, worked in Italy and Hollywood, navigated neorealism, epic spectacles, art-house auteurs and mainstream blockbusters. His life and work reflect not just the trajectory of one man, but the evolution of world cinema in the 20th century: from war-torn Italy to global media empires. He received the Academy’s Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award in 2001 as acknowledgement of his lifelong impact.

In this detailed examination—crafted in the voice of a film-historian—I will trace De Laurentiis’s early formation, his key partnerships and roles in Italian cinema, the structure of his producing strategy, his most significant films and collaborations, his achievements (including Oscars and other honours), and finally assess his legacy and lessons for today’s film professionals.

Early Life and Foundations

Born into the industrial outskirts of Naples, Dino was the third of seven children in a family whose income derived from pasta manufacturing. By his early teens he was selling spaghetti door-to-door, an experience he later described as his introduction to negotiation, logistics and showmanship. He then moved to Rome to attend the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in 1937–38, taking roles as actor, assistant director and prop man—a hands-on apprenticeship in cinema. By 1941 he founded his first production company, Realcine (sometimes stylized as Cine Real), which marked the beginning of his shift from technique to production leadership.

The war years interrupted film production and disrupted Italy’s studio system, but post-1945 proved fertile ground for innovation. De Laurentiis’s early producer credits at Lux Films included titles such as Il bandito (1946) and La figlia del capitano (1947), often under his elder brother Luigi’s assistance. But the breakthrough came with Riso amaro (Bitter Rice, 1949) directed by Giuseppe De Santis, a film that married neorealist subject matter (rice-field workers) with more commercial melodramatic elements, and announced De Laurentiis’s ambition: a cinema rooted in social reality, yet designed for mass and international appeal.

These early years taught him three crucial lessons that would underpin his career:

- Hybridisation of art and commerce: He believed film must speak to everyday reality but also attract audiences.

- International orientation: Even modest Italian films were conceived with foreign markets in mind.

- Scale and ambition: His sights were rarely confined to Italy alone; he aspired to global projects.

Role in Italian Cinema and the Post-War Resurgence

De Laurentiis entered film production at a transformative moment. In the immediate post-war period, Italian cinema was looking to rebuild, redefine itself, and to tell stories that resonated with the new realities of a devastated nation. The movement known as Italian Neorealism (films shot on location, non-professional actors, themes of poverty, war, reconstruction) became the dominant force for a time. De Laurentiis, rather than restricting himself to strict neorealist purity, saw opportunity in collaboration with neorealist directors and in broadening those themes for broader audiences.

In 1950, he formed a partnership with Carlo Ponti—the Ponti-De Laurentiis company—under which many key films were produced. Under this banner, De Laurentiis co-produced seminal films like La Strada (1954) and Le Notti di Cabiria (1957), which both won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. He thus positioned himself not only as a commercial producer but as a contributor to art cinema’s global prestige. At the same time he continued to back popular comedies, historical epics and genre films—raising the profile of Italian cinema abroad and turning Rome into “Hollywood on the Tiber.”

The creation of his own studio complex, Dinocittà, in the early 1960s exemplified his ambition to build infrastructure as well as produce films. However, rising costs and changing production realities in Italy forced him to sell it in the early 1970s. This pivot also marked his transition from Italian-centric production to full-scale international operation.

Because of his career trajectory, De Laurentiis straddles multiple eras: the immediate post-war Italian renewal, the 1950s and 60s Mediterranean co-production boom, and the transnational blockbusters of the 1970s-80s. His influence on Italian cinema is thus both stylistic and industrial: he helped reshape financing, distribution and co-production models that endure today.

Key Collaborations and Production Philosophy

Working with Auteur Directors

De Laurentiis’s producer role cannot be reduced simply to businessman-investor; he often worked closely with directors, choosing projects, selecting casts and shaping narratives. His collaboration with Federico Fellini via La Strada and Le Notti di Cabiria is perhaps most celebrated: these films are as much a product of their director as of De Laurentiis’s capacity to finance, support and export them. In the independent spirit of mid-century Italian cinema, the producer-director relationship was crucial, and De Laurentiis mastered that dynamic.

Beyond Fellini he worked with Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, Mario Monicelli, and later Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman. His eclectic roster of directors demonstrates his breadth and his refusal to be pigeon-holed. He recognised early that cinema was changing: national cinemas were increasingly in dialogue, and the producer role needed to adjust.

Genres, Spectacles and Blockbusters

From the late 1950s onward, De Laurentiis began engaging with large-scale epics and commercial spectacles: Ulysses (1954) with Kirk Douglas, War and Peace (1956) with Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda, the space and comic-book fantasy Barbarella (1968), and later Hollywood action films such as Serpico (1973), King Kong (1976) and Conan the Barbarian (1982). In each case, his strategy involved blending European location advantages, Italian technical crews, famous stars and large audiences.

His production strategy thus had four key pillars:

- Star casting – using known Hollywood name actors or rising international stars to guarantee audience attention.

- Location and cost efficiency – leveraging lower production costs in Italy or Europe while achieving high-production values.

- Genre versatility – not limiting himself to one kind of film; his portfolio ranges from social drama to fantasy, war epic to horror.

- Global distribution mind-set – he always considered films for international markets, not just for Italy.

Business Structures and Studio Models

In 1983 he founded the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG) in North Carolina, expanding into studio ownership and global distribution. Though DEG later collapsed in 1988, it represents his ambition to not only produce films but to build vertically-integrated media operations. Even when his projects failed financially (e.g., his expensive production of Dune (1984)), his willingness to experiment and risk large sums defined his producer profile: bold, ambitious, sometimes flawed—but never cautious.

Signature Films and Milestones

To appreciate De Laurentiis’s contribution, one must examine key films that mark his career arcs—from Italian post-war realism through international co-production to modern blockbusters.

- Bitter Rice (Riso amaro, 1949): A critical success and Italian export, this film of rice-field labourers was one of his early hits, establishing his producer credentials internationally.

- La Strada (1954): Directed by Fellini, produced by Ponti-De Laurentiis, this poetic drama of a clown, a brute and a woman is now widely considered a masterpiece, winning the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

- Le Notti di Cabiria (1957): Another Fellini collaboration, continuing De Laurentiis’s alignment with auteur cinema and global prestige.

- Serpico (1973): Directed by Sidney Lumet, starring Al Pacino, this American crime drama marks De Laurentiis’s full engagement with Hollywood and serious dramatic content.

- King Kong (1976): A high-cost remake of the classic 1933 film—his audacity in production scale is evident even though it divided critics.

- Blue Velvet (1986): Back in auteur territory, De Laurentiis produced David Lynch’s cult classic, showing that even in his later years he could still engage with provocative cinema.

- Hannibal (2001): A late-career commercial success, crucially securing his lasting income and demonstrating the longevity of his production enterprise.

These films illustrate the dual strands of his career: a commitment to artistic cinema (especially in Italy) and a keen sense for mass-market spectacle.

Awards, Accolades and Industry Recognition

Dino De Laurentiis’s achievements were recognised internationally. Among his honours:

- The films he produced La Strada and Le Notti di Cabiria both won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, demonstrating his early impact on world cinema.

- In 2001 he received the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, given for “consistent high quality of motion picture production.”

- He was honoured with lifetime awards at festivals and by professional bodies, such as the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement in 2003.

In addition to formal awards, his industry reputation as a creator of infrastructure (studios, production companies), a talent-spotter, and a link between Italian and American cinema solidified his position as one of film’s key producers of the 20th century.

Legacy and Critical Assessment

As a film expert might argue, De Laurentiis’s legacy lies less in a homogeneous body of work and more in his method, his ambition and his bridge-building between cinema systems. Several aspects merit emphasis:

1. Industrial Innovation

De Laurentiis exemplified the move from national cinema to transnational co-production. His ability to attract Hollywood stars to Italy, build studio facilities, and distribute globally helped change how films were financed and produced. The “Hollywood on the Tiber” phenomenon owes much to his work.

2. Cultural Intermediation

He brought Italian cinema into the global spotlight while also importing international aesthetics into Italy. His commitment to both auteur cinema and blockbuster spectacle shows a producer comfortable in both worlds—a rare trait.

3. Risk-Taking and Scale

Some of his failures (notably Dune, Waterloo, others) were spectacular, yet they underline his willingness to take on projects far beyond the safe and modest. This appetite for large scale defined his brand: if you saw the De Laurentiis name, you expected ambition.

4. Star-Making and Talent Nurturing

He helped develop careers—not just his own but those of actors like Silvana Mangano, later partnerships with directors, technicians and international stars. His role in identifying and packaging talent is a central part of his legacy.

5. Complex Critical Standing

Critics often pointed out the unevenness of his output: some masterpieces, some commercial flops. But that very unevenness is also testament to a career that refused complacency. As a historian might say: “The inconsistency is part of the point.” De Laurentiis was not a craftsman of minor perfection; he was a showman of major ambition.

Conclusion

Dino De Laurentiis remains one of the most compelling figures in film history—a producer whose name stands for ambition, diversity, internationalism and the intersection of artistry and commerce. His rise from selling pasta in Naples to producing films that shaped Italian cinema’s global reputation, and then to engaging in Hollywood blockbusters, reflects the shifts in the film industry itself.

For today’s filmmakers, producers and analysts, his career offers several lessons:

- Think globally: Production isn’t confined to local markets but encompasses international networks.

- Balance art and commerce: It’s possible to produce films with aesthetic ambition and audience appeal.

- Invest in infrastructure and talent: Your role as producer is not just transactional, but developmental.

- Embrace risk: Without risk, there is limited innovation; De Laurentiis’s failures and successes were both instructive.

- Adapt and evolve: He transitioned from Italian neorealism to Hollywood action films, showing that a long career demands flexibility.

In sum, De Laurentiis was not simply a film producer—he was a cinematic architect, a builder of bridges between nations, styles and eras. Though he passed away on November 11, 2010, at the age of 91, his imprint on cinema remains vivid. His name appears on credits that span world-famous masterpieces, genre innovations, commercial phenomena and cult classics. As long as films are made across borders, with stars, studios and global audiences, his model will remain relevant.