One of the most admired works of film is the Godfather trilogy, a soaring example of narrative that surpasses genre conventions to become something far more than the sum of its parts. Directed by Francis Ford Coppola and based on Mario Puzo’s bestselling novel, these three films—released in 1972, 1974, and 1990—chronicle the rise and fall of the Corleone crime family across five decades of American history. More than mere gangster films, they constitute an epic meditation on power, family, tradition, and the corruption of the American Dream.

Origins and Development

The genesis of The Godfather began with Mario Puzo’s 1969 novel, a work that emerged from the author’s desperate financial circumstances. Puzo, struggling with gambling debts and seeking commercial success, crafted a story that would become one of the best-selling novels of all time. The book’s blend of family saga and crime thriller struck a chord with readers, selling over nine million copies and spending 67 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list.

Paramount Pictures acquired the film rights to Puzo’s novel, initially viewing it as a low-budget exploitation film. The studio’s executives were skeptical about the project’s potential, seeing it merely as another entry in the gangster genre that had been largely dormant since the 1930s and 1940s. However, the involvement of Francis Ford Coppola as director would transform this modest project into something extraordinary.

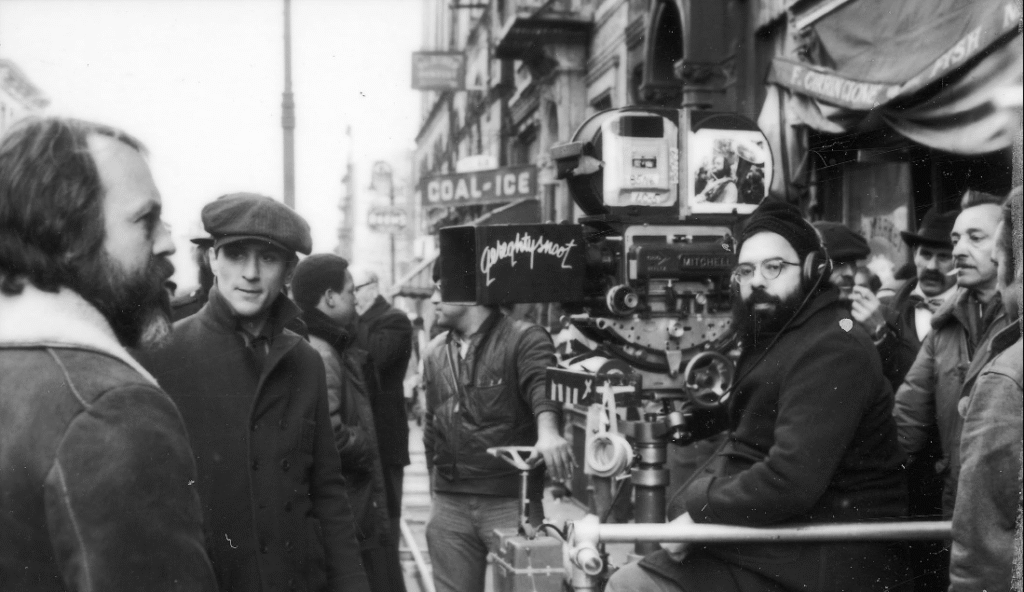

Coppola, then a young director with only a few films to his credit, was not Paramount’s first choice. The studio had approached several established directors, including Arthur Penn and Costa-Gavras, who declined the project. Coppola himself was initially reluctant, viewing the material as potentially exploitative. However, his perspective changed when he recognized the story’s deeper themes about family, power, and the immigrant experience in America.

The collaboration between Coppola and Puzo proved to be one of cinema’s most fruitful partnerships. Together, they adapted the sprawling novel into a screenplay that would preserve the book’s epic scope while creating a distinctly cinematic narrative. Their approach was meticulous, with both men committed to creating an authentic portrayal of Italian-American culture and the world of organized crime.

The First Film: A New Standard for Cinema

Released on March 24, 1972, The Godfather immediately established itself as something extraordinary. The film opens with one of cinema’s most iconic scenes: the wedding of Don Vito Corleone’s daughter Connie, intercut with the don receiving visitors in his darkened study. This masterful sequence, lasting nearly half an hour, introduces the audience to the Corleone family’s world while establishing the film’s central themes of loyalty, respect, and the complex moral universe that governs the characters’ lives.

Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Don Vito Corleone became the stuff of legend. His transformation into the aging patriarch was complete, from the cotton balls stuffed in his cheeks during auditions to the raspy, measured delivery that would become synonymous with the character. Brando’s performance was both intimidating and sympathetic, creating a character who commanded respect while revealing the humanity beneath the fearsome exterior.

Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone represented the heart of the trilogy’s narrative arc. Initially reluctant to join the family business, Michael evolves from war hero and college graduate to ruthless don, embodying the film’s exploration of how power corrupts even the most principled individuals. Pacino’s subtle performance charts Michael’s transformation with remarkable precision, showing how circumstances and choices gradually erode his moral foundations.

The supporting cast was equally exceptional, featuring James Caan as the hot-headed Sonny, Robert Duvall as the loyal consigliere Tom Hagen, and Diane Keaton as Kay Adams, Michael’s girlfriend who represents the legitimate world he ultimately abandons. Each performance contributed to the film’s rich tapestry of characters, creating a lived-in world that felt authentic and lived-in.

Coppola’s direction was marked by its attention to detail and commitment to authenticity. Every aspect of the production, from Gordon Willis’s shadowy cinematography to the period-accurate costumes and sets, was designed to immerse viewers in the Corleones’ world. The director’s decision to shoot many scenes in low light, earning Willis the nickname “The Prince of Darkness,” created an atmosphere of moral ambiguity that perfectly suited the story’s themes.

The film’s pacing was deliberately measured, allowing scenes to develop naturally and giving weight to every moment. This approach, unusual for the time, helped establish The Godfather as a new kind of American epic, one that valued character development and thematic depth over action and spectacle.

The Godfather Part II: Expanding the Vision

Released in 1974, The Godfather Part II represented an unprecedented achievement in sequel filmmaking. Rather than simply continuing the story, Coppola and Puzo created a complex narrative structure that told two interconnected stories: Michael Corleone’s continued descent into darkness in the 1950s, and the rise of his father Vito as a young man in early 20th-century America.

The parallel structure allowed the filmmakers to explore themes of legacy and repetition while contrasting the different paths taken by father and son. Robert De Niro’s portrayal of the young Vito Corleone was a masterpiece of performance, capturing Brando’s essence while creating a distinct character. De Niro’s Vito is driven by necessity and a desire to protect his family, his violence serving clear purposes within a moral framework he never abandons.

In contrast, Pacino’s Michael in Part II has become isolated and paranoid, his power built on fear rather than respect. The film shows how Michael’s pursuit of legitimacy and expansion has cost him everything he claimed to be protecting. His relationship with his wife Kay deteriorates, culminating in her devastating revelation about their lost child, while his treatment of his brother Fredo represents the ultimate betrayal of family bonds.

The film’s exploration of American history was equally sophisticated. The young Vito’s story takes place against the backdrop of early 20th-century immigration, showing how poverty and discrimination drove many Italian immigrants toward organized crime as one of the few available paths to prosperity and respect. The sequences set in Sicily and Little Italy are filmed with a golden, nostalgic quality that contrasts sharply with the cold, sterile world Michael inhabits in 1950s Nevada and Cuba.

Part II’s climax, featuring the attempted assassination of Michael in his Lake Tahoe compound, serves as both thrilling action sequence and symbolic representation of his isolation. Surrounded by enemies and unable to trust even his closest associates, Michael has achieved the power he sought while losing everything that made that power meaningful.

The film’s final scene, showing Michael alone after ordering the murder of his own brother, represents one of cinema’s most powerful endings. The parallel cutting between past and present, showing the warmth of the Corleone family’s earlier gatherings contrasted with Michael’s current isolation, creates a devastating portrait of how the pursuit of power can destroy the very things it claims to protect.

Technical Mastery and Visual Style

The Godfather trilogy’s technical achievements were as groundbreaking as its narrative innovations. Gordon Willis’s cinematography created a visual style that became synonymous with serious American filmmaking. His use of darkness and shadow was not merely atmospheric but thematically significant, reflecting the moral ambiguity that permeates the characters’ world.

Willis’s approach to lighting was revolutionary for its time. Rather than ensuring that every face was clearly lit, as was standard practice, he allowed shadows to obscure features, forcing viewers to lean in and pay closer attention. This technique created an sense of intimacy and complicity, making audiences feel as though they were eavesdropping on private conversations in a dangerous world.

The production design, led by Dean Tavoularis, was equally meticulous. Every detail, from the Corleone family compound to the restaurants and nightclubs where key scenes unfold, was researched and crafted to reflect the authentic world of mid-20th-century organized crime. The attention to period detail extended to costumes, cars, and even the smallest props, creating a complete and believable world.

Nino Rota’s musical score became as iconic as any element of the films. The main theme, with its haunting melody played on solo trumpet, perfectly captured the tragic nature of the Corleone saga. Rota’s music enhanced the emotional impact of key scenes while never overwhelming the drama, demonstrating the power of restraint in film scoring.

The editing, supervised by Coppola himself along with a team of skilled editors, was crucial to the films’ success. The deliberate pacing allowed scenes to breathe while building inexorable dramatic tension. The parallel editing in Part II, cutting between different time periods, required exceptional skill to maintain narrative clarity while building thematic resonance.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

The Godfather trilogy’s impact on American culture extends far beyond cinema. The films introduced phrases and concepts that became part of common discourse, from making someone “an offer he can’t refuse” to the importance of “going to the mattresses.” More significantly, the trilogy changed how Americans understood organized crime, moving beyond simple good-versus-evil narratives to explore the complex social and economic factors that create and sustain criminal enterprises.

The films’ portrayal of Italian-American culture was both celebration and critique. While some criticized the movies for perpetuating stereotypes about Italian-Americans and organized crime, others praised them for their authentic depiction of immigrant experiences and family traditions. The trilogy’s influence on subsequent portrayals of organized crime in film and television cannot be overstated, establishing conventions and expectations that continue to shape the genre.

The Godfather trilogy also marked a turning point in Hollywood’s relationship with serious filmmaking. The commercial success of these complex, deliberately paced character studies proved that audiences would embrace sophisticated narratives if they were well-crafted and authentically told. This success helped launch the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s, encouraging studios to support director-driven projects that prioritized artistic vision alongside commercial appeal.

The films’ influence on other directors has been profound and lasting. Filmmakers from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino have acknowledged their debt to Coppola’s achievement, and elements of The Godfather’s style and approach can be seen in countless subsequent films. The trilogy established new standards for epic filmmaking, showing how personal stories could illuminate broader themes about power, family, and American society.

The Third Chapter: Redemption and Resolution

The Godfather Part III, released in 1990 after a sixteen-year gap, faced the impossible task of concluding one of cinema’s greatest achievements. While generally considered the weakest entry in the trilogy, the film nonetheless provides important closure to Michael Corleone’s story while exploring themes of redemption and the possibility of escape from cycles of violence.

Set in 1979, Part III shows an aging Michael attempting to legitimize his empire while seeking redemption for his past crimes. His efforts to secure Vatican approval for a massive real estate deal bring him into conflict with corrupt church officials and rival crime families, while his relationship with his daughter Mary becomes the emotional center of the narrative.

Sofia Coppola’s performance as Mary Corleone was widely criticized, but the character’s function in the story remains important. Mary represents Michael’s attempt to create something pure and innocent in his world, making her ultimate fate all the more tragic. The film’s exploration of how children inherit the sins of their parents provides a fitting conclusion to the trilogy’s multi-generational saga.

Andy Garcia’s Vincent Mancini, Sonny’s illegitimate son, represents both continuity and change within the Corleone legacy. His hot-headed nature echoes his father’s while his loyalty to Michael demonstrates the enduring power of family bonds. Vincent’s eventual ascension to don suggests that while individuals may seek redemption, the institutions and traditions they create have their own momentum.

The film’s climax, set during a performance of the opera Cavalleria Rusticana, provides both spectacular action and thematic resolution. The parallel between the opera’s story of honor and revenge and Michael’s own situation creates layers of meaning while the assassination attempts that unfold during the performance bring the trilogy’s themes of art, culture, and violence into sharp focus.

Themes and Philosophical Depth

The Godfather trilogy’s enduring power stems from its exploration of timeless themes that resonate across cultures and generations. At its heart, the saga examines the relationship between family loyalty and moral compromise, asking whether it’s possible to protect those we love without destroying our own souls in the process.

The concept of honor runs throughout all three films, but its meaning evolves and becomes increasingly complex. Don Vito’s code of honor, while involving violence and crime, operates within clear moral boundaries and serves to protect family and community. Michael’s interpretation of honor becomes increasingly self-serving and destructive, ultimately isolating him from the very people he claims to be protecting.

The trilogy’s treatment of the American Dream is particularly sophisticated. The Corleone family’s rise represents both the promise and the corruption of American opportunity. While Don Vito achieves success and respect through his criminal enterprise, the costs of this achievement become increasingly clear as the story progresses. Michael’s pursuit of legitimacy and respectability reveals the hollow nature of power gained through violence and intimidation.

The films also examine the nature of tradition and change in American society. The Corleone family’s Sicilian traditions provide stability and identity but also perpetuate cycles of violence and revenge. The tension between old ways and new opportunities creates conflicts that drive much of the trilogy’s drama while reflecting broader changes in American society during the mid-20th century.

Performance and Character Development

The trilogy’s success rests largely on its exceptional ensemble of performances, with each actor creating fully realized characters that feel like real people rather than movie archetypes. Al Pacino’s transformation as Michael Corleone represents one of cinema’s greatest character arcs, showing how circumstances and choices can fundamentally alter a person’s nature.

In the first film, Michael is genuinely reluctant to join the family business, his horror at the violence around him appearing authentic. Pacino plays these early scenes with subtle vulnerability that makes Michael’s later transformation all the more shocking. By Part II, Michael has become cold and calculating, his interactions with family members marked by suspicion and manipulation. Pacino’s performance shows how the role of don has consumed Michael’s original personality, leaving only the facade of power.

Marlon Brando’s Don Vito remains one of cinema’s most memorable characters, despite appearing in only one complete film. Brando’s physical transformation was remarkable, but more important was his ability to suggest both menace and warmth, creating a character who could be simultaneously frightening and sympathetic. His scenes with his grandson in the garden provide some of the trilogy’s most touching moments, showing that even the most powerful men are ultimately mortal.

Robert De Niro’s young Vito in Part II creates a complete character while honoring Brando’s iconic performance. De Niro’s Vito is more impulsive and emotional than the older version, his actions driven by clear motivations and understandable goals. The parallel between his rise and Michael’s decline provides Part II with its emotional and thematic structure.

The supporting performances throughout the trilogy are equally strong, from James Caan’s explosive Sonny to Robert Duvall’s steadfast Tom Hagen. Each actor brings depth and authenticity to their role, creating a ensemble that feels like a real family rather than a collection of movie characters.

Conclusion: An Enduring Masterpiece

The Godfather trilogy represents the pinnacle of American filmmaking, a work that combines spectacular entertainment with profound artistic achievement. Nearly fifty years after the release of the first film, the trilogy continues to influence filmmakers and captivate audiences around the world.

The films’ exploration of family, power, and moral compromise remains as relevant today as it was upon their initial release. In an era of increasing polarization and moral uncertainty, the trilogy’s complex examination of how good people can make terrible choices feels particularly timely. The Corleone saga reminds us that the road to hell is often paved with good intentions, and that the pursuit of power inevitably corrupts even the most principled individuals.

From a purely cinematic standpoint, the trilogy established new standards for epic filmmaking that continue to influence directors today. The careful attention to character development, the meticulous period detail, and the sophisticated narrative structure created a template for serious popular filmmaking that remains unmatched.

The Godfather trilogy stands as proof that popular entertainment and artistic achievement need not be mutually exclusive. By treating their subject matter with respect and complexity, Coppola and his collaborators created films that work on multiple levels – as thrilling crime dramas, as intimate family sagas, and as profound meditations on American society and human nature.

In the end, The Godfather trilogy endures because it tells the truth about power and its costs. In showing us the Corleone family’s rise and fall, these films reveal fundamental truths about ambition, loyalty, and the price of success in American society. They remind us that every choice has consequences, and that the pursuit of power, no matter how well-intentioned, ultimately destroys the very things it seeks to protect.

The trilogy’s final image – Michael Corleone dying alone in his garden, surrounded by the symbols of the power he accumulated but unable to enjoy the simple pleasures of family and peace – serves as a powerful warning about the hollow nature of success achieved through violence and compromise. It is this unflinching examination of moral complexity, combined with masterful filmmaking craft, that ensures The Godfather trilogy’s place among cinema’s greatest achievements.