The term “exploitation film” conjures up a potent cocktail of images: lurid posters screaming sensational titles, scenes of graphic violence or sexual content, and a general air of transgression. These aren’t your mainstream blockbusters; they operate in the cinematic underbelly, often deliberately pushing boundaries and reveling in the taboo. But to simply dismiss them as low-budget trash is to overlook a fascinating and multifaceted genre (or perhaps, more accurately, a collection of subgenres and approaches) that has reflected, and sometimes even influenced, societal anxieties and cultural shifts for decades.

At its core, an exploitation film is one that attempts to succeed financially by capitalizing on sensational or controversial subject matter. This can range from graphic violence and sexual content to outlandish premises and the exploitation of current social trends or fears. The emphasis is often on the shocking, the titillating, and the outrageous, frequently with a disregard for conventional narrative structure, nuanced character development, or high production values.

However, the landscape of exploitation cinema is far from monolithic. It encompasses a diverse array of subgenres, each with its own distinct characteristics and historical context. Understanding these nuances is crucial to appreciating the complex and often contradictory nature of these films.

The Seeds of Scandal: Early Exploitation

The roots of exploitation can be traced back to the early days of cinema. Even in the silent era, films that dealt with social issues like prostitution, drug use, and venereal disease, often presented with a moralistic veneer but with undeniable sensationalism, drew audiences eager for a glimpse into the forbidden. These early “social hygiene” films, while ostensibly cautionary tales, often lingered on the very aspects they purported to condemn.

The advent of sound and the loosening of censorship in certain territories during the early to mid-20th century paved the way for more explicit content. Films like Reefer Madness (1936), with its hilariously exaggerated depiction of marijuana’s supposed dangers, became cult classics, unintentionally highlighting the exploitative nature of fear-mongering narratives.

The Golden Age of Grindhouse: Genre Proliferation

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed an explosion of exploitation cinema, fueled by factors such as changing social mores, the rise of independent filmmaking, and the emergence of the “grindhouse” theater circuit. These down-and-dirty cinemas, often located in urban centers, showcased a constant rotation of low-budget, sensational fare, catering to a diverse audience seeking thrills and escapism.

This era saw the proliferation of distinct exploitation subgenres, each tapping into specific cultural anxieties and desires:

- Sexploitation: This broad category encompasses films that heavily feature nudity and sexual situations, often with flimsy plots serving as mere excuses for titillation. From softcore nudie flicks to more explicit adult films, sexploitation explored (and often exploited) the burgeoning sexual revolution.

- Violence and Gore: The increasing tolerance for on-screen violence led to the rise of “mondo” films (purporting to be documentaries showcasing shocking real-world footage), splatter films (emphasizing graphic gore and visceral effects), and violent crime dramas. These films often pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable to depict on screen.

- Blaxploitation: Emerging in the early 1970s, blaxploitation films were a complex phenomenon. While often criticized for their stereotypical portrayals and exploitation of Black culture, they also provided opportunities for Black actors and filmmakers, offered narratives centered on Black experiences (albeit often within a crime-ridden context), and resonated with Black audiences who were largely ignored by mainstream cinema. Films like Shaft (1971) and Foxy Brown (1974) became cultural touchstones.

- Women in Prison Films: This subgenre, often featuring scantily clad women subjected to brutal treatment and exploitation within prison walls, played on themes of female vulnerability and resilience, often with a strong dose of sadism and titillation.

- Rape-Revenge Films: These controversial films, often sparked by anxieties surrounding sexual violence, typically depict a female protagonist who seeks violent retribution against her attackers. While some critics argue they offer a cathartic, albeit problematic, outlet for female rage, others condemn them for their exploitative depiction of sexual assault.

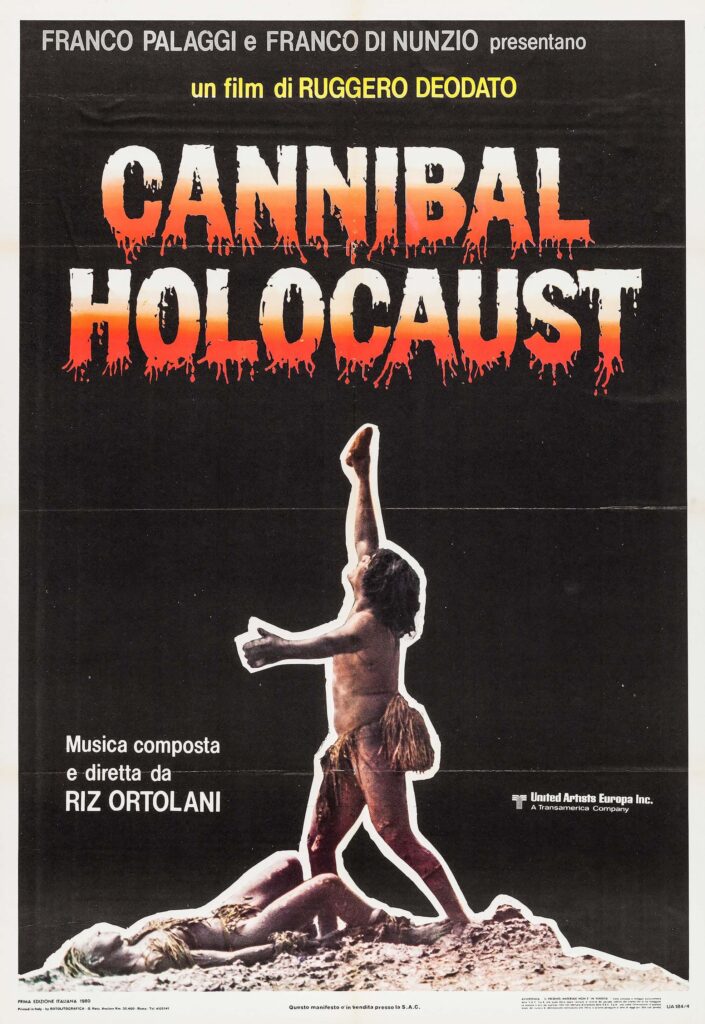

- Horror Exploitation: This subgenre blends the tropes of horror with the sensationalism of exploitation, often featuring excessive gore, supernatural elements, and themes of sexual perversion or societal breakdown. Films like The Last House on the Left (1972) and Cannibal Holocaust (1980) exemplify this often shocking and disturbing subgenre.

- Kung Fu Exploitation: The martial arts craze of the 1970s led to a wave of low-budget kung fu films, often imported from Hong Kong or produced domestically, featuring acrobatic fight choreography, outlandish plots, and a focus on action over nuanced storytelling.

- Biker Films: These films, often capitalizing on the counter-culture image of motorcycle gangs, typically featured rebellious characters, violence, and a sense of freedom and lawlessness.

- Disaster Exploitation: Inspired by the success of big-budget disaster films, low-budget exploitation versions often featured cheaper special effects, more gratuitous violence, and a focus on sensationalistic scenarios.

The Grindhouse Legacy: Influence and Evolution

While the heyday of the grindhouse era eventually faded with the rise of home video and multiplex cinemas, the influence of exploitation films remains significant. Many contemporary filmmakers, often those who grew up watching these films, cite them as a key influence on their work. The DIY aesthetic, the willingness to tackle taboo subjects, and the emphasis on visceral impact have all found their way into mainstream and independent cinema.

Furthermore, the spirit of exploitation lives on in various forms:

- Cult Cinema: Many exploitation films have achieved cult status, attracting dedicated fan bases who appreciate their transgressive nature, their often unintentional humor, and their unique place in cinematic history.

- Retro Revivals: The grindhouse aesthetic has experienced a resurgence in recent years, with filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez deliberately emulating the style and spirit of 1970s exploitation cinema in films like Death Proof (2007) and Machete (2010).

- Independent Filmmaking: The low-budget, anything-goes attitude of exploitation continues to inspire independent filmmakers who operate outside the mainstream studio system, allowing them to explore unconventional narratives and push creative boundaries.

- Video Nasties: In the UK, a moral panic in the early 1980s led to a list of films, dubbed “video nasties,” that were deemed obscene and subject to censorship. Many of these films were low-budget exploitation titles, and the controversy surrounding them only amplified their notoriety and cult appeal.

The Ethical Tightrope: Exploitation vs. Exploration

The very term “exploitation” carries a negative connotation, and it’s crucial to grapple with the ethical implications of these films. Critics often accuse them of being misogynistic, racist, gratuitously violent, and of profiting from the suffering and degradation of marginalized groups. These are valid concerns that cannot be dismissed.

However, some argue that exploitation films can also serve as a distorted mirror reflecting societal anxieties, prejudices, and taboos. By exaggerating and sensationalizing certain aspects of reality, they can inadvertently expose underlying issues and provoke discussion, albeit often in a crude and uncomfortable manner.

Furthermore, the line between exploitation and exploration can be blurry. A film that delves into difficult or controversial subject matter might be accused of exploitation if it is perceived as gratuitous or lacking in artistic merit. Conversely, a film that uses sensational elements to draw attention to important social issues might be seen as more justifiable. The intent of the filmmakers, the context of the time, and the critical reception all play a role in this complex ethical evaluation.

Beyond the Shock Value: Finding Meaning in the Margins

While many exploitation films are undoubtedly crude and disposable, others possess a certain raw energy, a subversive spirit, or even a strange kind of artistic merit. Their low-budget ingenuity can lead to creative filmmaking techniques, and their willingness to break taboos can sometimes open up spaces for marginalized voices or perspectives, even if those perspectives are filtered through a sensationalistic lens.

For example, while blaxploitation films often relied on stereotypes, they also provided opportunities for Black actors and filmmakers to tell stories that were otherwise absent from mainstream cinema. Similarly, some women-in-prison films, despite their exploitative elements, can be interpreted as exploring themes of female solidarity and resistance within oppressive systems.

Ultimately, engaging with exploitation films requires a critical and nuanced perspective. It’s important to acknowledge their problematic aspects while also recognizing their historical context, their influence on cinema, and the occasional glimmers of social commentary or artistic innovation that can be found within their often lurid frames.

A Journey Through Subgenres: A Closer Look

To truly understand the breadth and depth of exploitation cinema, it’s helpful to delve deeper into some of its key subgenres:

1. Mondo Films:

Emerging in the 1960s with films like Mondo Cane (1962), mondo films purported to be documentaries showcasing bizarre, shocking, and often gruesome real-world practices and rituals from around the globe. These films often blurred the lines between fact and fiction, employing staged scenes and sensationalized narration to maximize their shock value. They tapped into a Western fascination with the “exotic” and the taboo, often with a strong dose of cultural insensitivity and outright fabrication. Films like Faces of Death (1978), with its graphic depictions of death and violence, became notorious examples of this subgenre, raising serious ethical questions about the exploitation of real suffering for entertainment.

2. Sexploitation:

This vast category encompasses films that primarily focus on nudity and sexual situations. Early sexploitation films were often presented under the guise of educational or sociological documentaries, such as the nudie-cuties of the 1950s and 60s, which featured scantily clad women in innocuous settings. As censorship loosened, the genre evolved into more explicit territory, with films featuring increasingly suggestive and eventually explicit content, often with minimal plot or character development. These films catered to a male gaze and often objectified women, contributing to ongoing debates about the representation of sexuality in cinema.

3. Blaxploitation:

A significant cultural phenomenon of the 1970s, blaxploitation films were aimed at Black audiences and featured Black actors in leading roles, often in urban crime narratives. While criticized for perpetuating stereotypes of Black criminality and violence, these films also provided a platform for Black talent and addressed issues of racial inequality and social injustice, albeit often within a sensationalized framework. Iconic films like Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Super Fly (1972), and Coffy (1973) captured the spirit of the era and resonated with Black audiences who were largely ignored by mainstream Hollywood. The genre’s complex legacy continues to be debated, with some celebrating its empowerment of Black representation and others critiquing its reliance on harmful tropes.

4. Women in Prison Films:

This subgenre, popular in the 1970s, typically depicted women incarcerated in brutal and often sexually charged prison environments. These films often featured gratuitous nudity, violence against women, and themes of lesbianism, often catering to a male voyeuristic gaze. While some interpretations suggest these films could be seen as exploring themes of female oppression and resistance within confined spaces, the overwhelming emphasis on exploitation and degradation raises significant ethical concerns. Films like Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS (1975) exemplify the more extreme and controversial aspects of this subgenre.

5. Rape-Revenge Films:

These highly controversial films center on a protagonist, often female, who seeks violent retribution against those who have sexually assaulted her. While some argue that these films offer a cathartic, albeit problematic, exploration of female rage and the desire for justice in the face of sexual violence, others condemn them for their exploitative depiction of sexual assault and their often brutal and sensationalized violence. Films like Day of the Woman (also known as I Spit on Your Grave, 1978) remain highly divisive and spark intense debate about the ethics of representing sexual violence on screen.

6. Horror Exploitation:

This subgenre blends the tropes of horror with the sensationalism of exploitation, often pushing the boundaries of gore, violence, and sexual perversion. Films like Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), which explicitly depicted rape and brutal violence, and Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1980), notorious for its graphic depictions of violence and animal cruelty, exemplify the extreme and often disturbing nature of this subgenre. These films often aimed to shock and provoke audiences, challenging the limits of on-screen depiction.

7. Kung Fu Exploitation:

The global popularity of martial arts films in the 1970s led to a surge of low-budget kung fu exploitation films, often imported from Hong Kong or produced domestically. These films typically featured acrobatic fight choreography, outlandish plots, and a focus on action and violence over nuanced storytelling. While often lacking in high production values, some of these films showcased impressive martial arts talent and contributed to the global appreciation of kung fu cinema. Films like Five Fingers of Death (1972) and Enter the Dragon (1973), while having higher production values, paved the way for a flood of lower-budget imitators.

8. Biker Films:

Capitalizing on the counter-culture image of motorcycle gangs, biker exploitation films typically featured rebellious characters, violence, drug use, and a sense of freedom and lawlessness. These films often portrayed biker gangs as outsiders challenging societal norms, sometimes with a romanticized or sensationalized perspective. Films like The Wild Angels (1966) and Easy Rider (1969), while having more artistic aspirations, helped establish the tropes that later, more exploitative biker films would embrace.

9. Disaster Exploitation:

Following the success of big-budget disaster films in the 1970s, low-budget exploitation versions emerged, often featuring cheaper special effects, more gratuitous violence, and sensationalistic scenarios. These films aimed to capitalize on the public’s fascination with large-scale catastrophes, often with a more lurid and less nuanced approach than their mainstream counterparts.

The Enduring Appeal (and Repulsion)

The appeal of exploitation films is complex and multifaceted. For some, it lies in the transgressive nature of these films, their willingness to venture into taboo territories that mainstream cinema often avoids. They can offer a glimpse into the darker corners of human experience and societal anxieties, albeit often in a crude and sensationalized manner.

For others, the appeal might be purely aesthetic – the low-budget ingenuity, the over-the-top performances, the raw energy, and the sheer audacity of these films can be strangely captivating. The “so bad it’s good” phenomenon is often at play, with audiences finding a perverse enjoyment in the films’ flaws and excesses.

However, the very elements that attract some viewers are precisely what repel others. The graphic violence, the sexual exploitation, and the often problematic representations of marginalized groups can be deeply offensive and ethically questionable. It’s crucial to approach these films with a critical eye, acknowledging their potential for harm while also recognizing their place in cinematic history and their occasional, albeit often unintentional, insights into cultural anxieties.

Conclusion: A Complicated Legacy

Exploitation films occupy a unique and often uncomfortable space in the cinematic landscape. They are a testament to the power of sensationalism, the allure of the forbidden, and the enduring human fascination with the extreme. While many of these films are undoubtedly crude, offensive, and ethically problematic, they also offer a glimpse into the underbelly of society, reflect changing cultural mores, and have exerted a surprising influence on subsequent generations of filmmakers.

Understanding exploitation cinema requires a willingness to engage with its complexities and contradictions. It demands a critical perspective that acknowledges both its potential for harm and its occasional, accidental insights. These films may not always be pleasant or easy to watch, but they remain a vital, if often disreputable, part of our cinematic history, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the societies we inhabit. Their legacy continues to spark debate about the boundaries of taste, the ethics of representation, and the enduring power of the moving image to shock, provoke, and even, in their own strange way, reflect the raw nerve of the human experience.