Seijun Suzuki emerged as one of Japan’s most distinctive cinematic voices during the postwar period, transforming studio genre assignments into wildly innovative works of personal expression. While initially overlooked as a mere B-movie director, Suzuki’s fearless experimentation with narrative structure, composition, and color gradually earned him recognition as a visionary filmmaker whose influence extends far beyond Japanese cinema.

The Studio Rebel

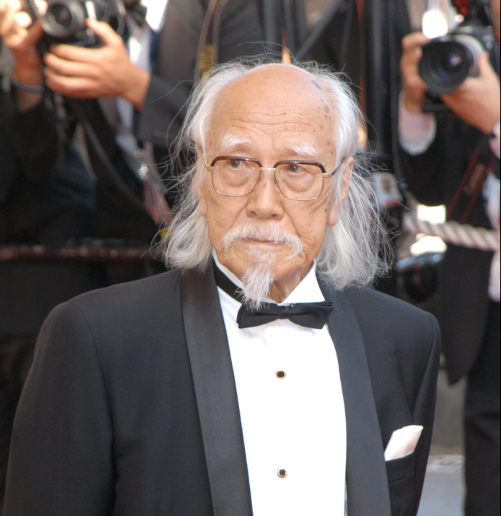

Born in 1923 in Tokyo, Suzuki’s early career was shaped by his military service during World War II and the subsequent cultural upheaval of postwar Japan. After joining Nikkatsu Studios in 1954, he began directing films within the constraints of the studio system. What initially appeared to be routine gangster films and crime thrillers gradually evolved into something far more subversive and challenging.

Suzuki’s relationship with Nikkatsu was notoriously contentious. The studio expected commercial entertainments; Suzuki delivered increasingly abstract, stylized films that bore his unmistakable signature. This tension reached its breaking point in 1967 when Nikkatsu fired Suzuki after the release of “Branded to Kill,” citing the film as “incomprehensible” and a commercial failure. This infamous dismissal would inadvertently cement his reputation as an uncompromising artist.

Stylistic Revolution

Suzuki’s visual style defied convention at every turn. His early works already showed glimpses of his maverick sensibilities, but it was during the mid-1960s that his aesthetic fully crystallized into something truly revolutionary. Several distinctive elements define the Suzuki style:

Disruptive Narrative

Suzuki routinely abandoned traditional storytelling logic in favor of dreamlike progressions. In films like “Tokyo Drifter” (1966) and “Branded to Kill” (1967), narrative coherence takes a back seat to visceral imagery and symbolic juxtapositions. Scenes don’t simply progress—they collide, fragment, and transform with hypnotic irregularity.

Bold Visual Composition

Suzuki’s frame compositions regularly break established cinematic rules, employing extreme angles, disorienting perspectives, and negative space in ways that create tension and visual poetry. His characters might be pushed to the edge of the frame or filmed through obstacles, challenging viewers’ perception and creating a distinct sense of unease.

Explosive Color

Beginning with “Gate of Flesh” (1964), Suzuki’s use of color became increasingly expressionistic. In “Tokyo Drifter,” entire settings are bathed in unnatural monochromatic schemes—a nightclub glows in ethereal blue light, while another sequence unfolds in stark white emptiness. These bold color choices serve emotional and thematic purposes rather than realistic representation.

Theatrical Artifice

Suzuki never aimed for realism. Instead, his films embrace artificiality, featuring obviously fake sets, theatrical lighting, and stylized performances. This deliberate artifice creates a heightened reality that simultaneously distances viewers while drawing them deeper into the film’s emotional core.

Essential Filmography

While Suzuki directed nearly 40 feature films, several stand as definitive works that showcase his unique vision:

“Youth of the Beast” (1963)

This yakuza thriller marked Suzuki’s first major artistic breakthrough. While ostensibly a crime film, its unconventional framing, violent mood shifts, and expressionistic use of color signaled Suzuki’s emerging artistic ambitions. The film follows an ex-cop infiltrating rival gangs, but the plot serves primarily as a framework for Suzuki’s increasingly bold visual experiments.

“Gate of Flesh” (1964)

Set in the ruins of postwar Tokyo, this unflinching drama follows a group of prostitutes surviving in the devastated city. Suzuki codes each woman with a specific color costume, creating a visual system that reflects their psychological states. The film’s frank sexuality and amoral tone shocked audiences, while its visual audacity demonstrated Suzuki’s growing confidence.

“Tokyo Drifter” (1966)

Perhaps Suzuki’s most accessible masterpiece, this yakuza film follows hitman Tetsu “Phoenix” Hondo as he wanders Japan after his boss disbands their gang. The film’s pop-art aesthetic, surreal musical sequences, and bold color experimentation create an unforgettable visual experience. The white-suited protagonist moves through increasingly abstract environments, culminating in a showdown in a nightclub of pure theatrical artifice.

“Branded to Kill” (1967)

The film that ended Suzuki’s Nikkatsu career remains his most radical achievement. Following the downfall of Japan’s “Number 3 Killer,” the film abandons narrative logic for a series of increasingly bizarre sequences. With its sexual obsessions, death symbolism, and fractured structure, “Branded to Kill” represents Suzuki at his most uncompromising and influential.

“Taisho Trilogy” (1980-1991)

After a decade-long exile from filmmaking following his Nikkatsu firing, Suzuki returned with this loose trilogy of period films set during Japan’s Taisho era (1912-1926). “Zigeunerweisen” (1980), “Kagero-za” (1981), and “Yumeji” (1991) explore Japanese identity during a time of rapid westernization, combining ghost story elements with even more radical formal experimentation.

Enduring Influence

Suzuki’s unconventional approach to cinema has influenced filmmakers around the world. Directors including Jim Jarmusch, Quentin Tarantino, Wong Kar-wai, and John Woo have acknowledged their debt to Suzuki’s visual innovations and rebellious spirit. His willingness to subvert genre expectations while creating mesmerizing visual experiences continues to resonate with filmmakers pushing against commercial and artistic boundaries.

Perhaps most significantly, Suzuki demonstrated how a filmmaker could work within commercial constraints while maintaining artistic integrity. His B-movie assignments became vehicles for profound artistic expression, proving that true innovation could emerge from even the most restrictive studio environments.

Rehabilitation and Recognition

After winning a lawsuit against Nikkatsu for wrongful termination, Suzuki gradually found new opportunities to direct. While his output became less frequent, his artistic vision remained intact. Critical reassessment of his work began in earnest during the 1980s, with international film festivals celebrating his unique contributions to cinema.

By the time of his death in 2017 at age 93, Suzuki had transitioned from industry outcast to revered master. His films, once dismissed as incomprehensible, are now recognized as pioneering works that expanded cinema’s visual and narrative possibilities.

Legacy of Defiance

What makes Suzuki’s achievements particularly remarkable is the context in which they emerged. Working within the rigid studio system of postwar Japan, his rebellion wasn’t merely aesthetic but represented a broader challenge to authority and convention. His films reflect the tensions of Japan’s postwar identity crisis, capturing the disorientation of rapid modernization and western influence.

Suzuki’s cinema ultimately celebrates individualism in the face of crushing conformity—a theme embodied by both his characters and his own career trajectory. In a Japanese film industry that prized technical perfection and narrative clarity, Suzuki chose disruption, ambiguity, and personal expression.

His legacy reminds us that true artistic innovation often emerges from outsiders willing to challenge established systems. The very qualities that made his films “incomprehensible” to studio executives in the 1960s are precisely what ensures their continuing relevance and influence today.