Why these three films still talk to us—by showing what can’t be said

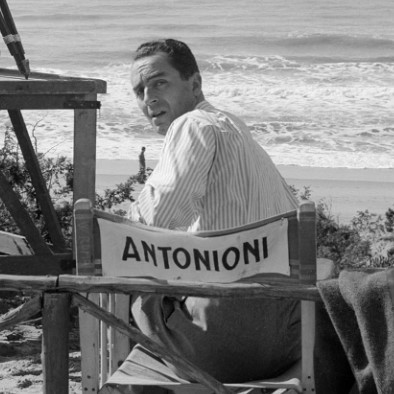

Michelangelo Antonioni’s so-called “Trilogy of Incommunicability”—L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L’Eclisse (1962)—is one of those cinematic runs that doesn’t just define a director; it rearranges how we look, listen, and wait. For me, these films feel like a patient hand on the shoulder during a loud party; they ask you to lean in, to pay attention to what doesn’t happen, to cherish the pause rather than the punchline. They are not puzzles designed to be solved; they are mirrors for the modern soul—distorted not by tricks but by our own emptiness, our own urban distances, our own beautifully designed rooms where words go to die.

Monica Vitti’s presence runs like a current through all three films, as if she were the tuning fork for Antonioni’s frequencies. Her faces are not blank; they are filled with illegible weather, a consciousness we can’t calculate, which is precisely why we keep looking. Around her orbit characters who should be happy—wealthy, athletic, connected—but affluence turns out to be the best soundproofing money can buy.

If Italian Neorealism turned its lens toward the rubble of postwar life, Antonioni points his to the clean lines and polished surfaces that came after the rubble was cleared: boardrooms, glass walls, stock exchanges, chic apartments, seaside rocks that look eternal precisely because we are not. The trilogy’s nickname is accurate thematically but undersells the breadth of Antonioni’s critique. These are films about failed transmissions—yes—but also about the spaces that interfere with those transmissions: architectural grids, wind-swept islands, financial markets, party circuits, and streets that forget we were ever standing there.

What follows is a map—part love letter, part field guide—to these three quiet earthquakes of modern cinema.

The shift from Neorealism to modernity’s malaise

To feel how radical Antonioni is, it helps to remember where Italian cinema had just been. Neorealism’s ethics and aesthetics—location shooting, nonprofessional actors, moral urgency—answered the emergency of the late 1940s. But by the end of the 1950s, Italy was in the economic boom: industry humming, design flourishing, middle classes expanding. The problems did not vanish; they changed temperature. Hunger ceded to ennui; rubble became reinforced concrete; the cruelty of want gave way to the cruelty of options.

Antonioni’s characters don’t starve; they drift. And he doesn’t moralize. He documents the drift through a new syntax: long takes, ellipses, architectural framing that makes people look as provisional as furniture. Sound becomes a meteorology—wind across stone, traffic under conversations, the clatter of a trading floor swallowing human voices whole. Giovanni Fusco’s spare, nearly abstract music sneaks in like a thought you didn’t know you were thinking. The result is a cinema of surface and depth that refuses the easy catharsis of plot.

L’Avventura (1960): Disappearance as structure

The vanishing that reveals everything else

On a yachting trip among the jagged islands off Sicily, Anna disappears. This is the hinge on which L’Avventura turns—but not the kind of hinge genre cinema would use. There is no culprit neatly waiting at the end of a corridor—only corridors. The film begins as if it were a mystery yet dissolves into a study of how desire migrates. Anna’s boyfriend Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) and her friend Claudia (Monica Vitti) search for her and—almost tenderly, almost cruelly—begin to replace the missing person with a romance that fills the hole without healing it.

In a conventional movie, Anna’s absence would be a problem to solve. For Antonioni, it is a fact to live with. The search becomes a tour of spaces that speak louder than the characters: an island made of rough stone where the wind is the protagonist; baroque towns whose geometries promise order and deliver confusion; hotel corridors where human footsteps echo like questions that will never be answered. The more they search, the more the world expands and their certainty contracts. The landscape isn’t background; it’s the interlocutor that never replies.

Mise-en-scène as psychology

Look at how Antonioni blocks actors against edges of buildings or frames them within windows and doorways. Characters occupy liminal strips—balconies, thresholds, ledges—spaces that visually encode their psychological state. The composition is never fussily symmetrical; it’s precarious, an equilibrium of discomfort. Even the camera seems to wait rather than chase, as if reluctant to impose a meaning that the characters themselves cannot find.

Claudia’s face and the ethics of attention

Monica Vitti gives the film its moral weather. Claudia is sincere but unstable—not a coquette so much as a person whose desire cannot find a resting place. Vitti’s performance is a study in micro-shifts: a happiness that recoils from its own arrival, a suspicion that tenderness might only be a form of self-forgetting. Antonioni never mocks her fluctuations; he respects them. The film asks us to consider that inconsistency can be a truth rather than a defect.

A non-ending that feels like the only honest ending

The closing image—Claudia’s hand on Sandro’s shoulder as he weeps after a petty infidelity—refuses closure. It is neither forgiveness nor condemnation. It is an acknowledgment: we are not enough for each other, but we are here. That gesture, tiny and seismic, is Antonioni’s reply to melodrama. He offers—against the pleasing lies of cinema—something closer to life: fragile, provisional, ongoing.

La Notte (1961): Night as an X-ray

Milan’s glass and the decline of a marriage

If L’Avventura is a geography of absence, La Notte is a diagnostic. Over a single day and night in Milan, Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni), a successful writer, and Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) visit a dying friend, attend a book event, wander the city, and drift into a high-society party. Nothing “big” happens; everything big happens. The marriage frays in slow motion, and Antonioni runs an X-ray through the night to show us the faint cracks in the bone of love.

The architecture of alienation

Milan in La Notte is steel and glass, a city that looks like the future and feels like no one’s home. You can see people reflected in windows and not know whether you are watching them or their ghosts. The film’s compositions take advantage of these modern surfaces, making characters double and triple as reflections pile up, an elegant technique to literalize self-estrangement.

At the party thrown by an industrialist, money lubricates everything except intimacy. Lidia slips away to wander through the city, and her ambulatory grief is one of the film’s great passages—an urban dérive that renounces both fight and flight for a third option: erasure. The city does not judge her; it absorbs her.

Valentina: the lucid mirror

Enter Valentina (Monica Vitti), the industrialist’s daughter, who becomes a kind of lucid mirror for Giovanni. She is attractive but, more importantly, attuned. She understands more than she says, and what she withholds isn’t coyness; it’s mercy. Their flirtation is not a moral breach; it’s an index of what’s missing elsewhere. Valentina’s manner—curious, careful—makes Giovanni’s professional emptiness visible to himself. He’s celebrated for words that no longer move him.

The morning after as verdict

La Notte ends without theatrics. In a deserted, dewy morning space, Giovanni and Lidia confront themselves. They attempt to restage desire, as if reciting vows might reboot the marriage. It doesn’t. The film leaves us not with a break but with a vacuum that neither romance nor resignation can fill. This is Antonioni’s most surgical film, the one that proves he can carve a wound without raising his voice.

L’Eclisse (1962): Markets, weather, and the final silence

Love in the time of speculation

L’Eclisse pushes the trilogy’s logic to its formal limit. In Rome, Vittoria (Monica Vitti) ends one relationship and drifts toward Piero (Alain Delon), a young stockbroker whose office—the Roman stock exchange—is a cacophony of numbers, gestures, and shouted bets. If La Notte showed how glass can keep people apart, L’Eclisse demonstrates how capital can convert emotion into noise. The exchange sequences are not background; they’re a thesis. Here, language is not for communion but for advantage. The choreography of hands and voices becomes a parody of dialogue: communication without meaning.

The EUR and the afterimage of the future

Much of the film unfolds in the EUR district, that rationalist landscape of wide avenues and abstract monuments. The streets look designed for parades of no one, and Antonioni uses their clean geometry to thin out the human presence. Vittoria is often a small figure against the facades; the camera holds and holds while nothing happens—and then, somehow, that becomes the event.

Objects as unreliable narrators

Antonioni is a master of object dramaturgy. Watch how a lamp or a barrel of water or a car accrues meaning not through symbolism but through duration. Piero’s relationship to his Alfa Romeo tells you more about his hierarchy of values than any confession could. Vittoria’s delicate gestures with mundane items—an earring, a glass, a fan—are micro-dramas of hesitation.

The ending: seven minutes without protagonists

The famous ending sequence is one of the bravest gestures in narrative cinema: the film continues without its leads. Locations we recognize—bus stops, corners, a fence—float by. Passersby who were extras become the only “characters.” Ambient sounds knit the space together. Day slides toward night. We await the rendezvous that does not occur. It is not simply that Vittoria and Piero fail to show; it’s that the film imagines a world that doesn’t require them. The eclipse of the title is not astronomical; it’s ontological—the eclipse of personhood by environment, of intention by pattern, of story by time.

Style as ethics: what Antonioni refuses to do

Ellipsis instead of exposition

In classical storytelling, every disappearance begs an explanation. Antonioni leaves holes. Those holes are not lazy; they are ethical. He refuses to fabricate certainty where human life offers none. The audience is asked not to solve but to stay. If you’ve ever sat with a friend in grief and known there was nothing to say, you already speak Antonioni.

Duration instead of drama

He gives us time—to notice the architecture, to hear wind, to track footsteps. Duration lets the background migrate to foreground, so that place becomes not a setting but a pressure. The long take is not a flex; it’s an invitation to watch the world without interruption.

Silence as a full register

Silence here is not empty; it’s the sum of what can’t be said. The sound design (street traffic, rustle, mechanical hum) is never perfunctory. Often, environmental sound is the film’s most articulate voice, which is why dialogue can be ordinary without being irrelevant.

Blocking and negative space

Antonioni’s famous use of negative space—air above heads, margins wider than necessary—recalibrates our sense of human scale. People look dwarfed by spaces designed for them. The frames yield an anthropology: modernity is full of rooms we built for ourselves and no longer fit inside.

Vitti, Ferzetti, Mastroianni, Moreau, Delon: faces as landscapes

I am tempted to call Monica Vitti the cosmic constant of the trilogy. Her faces—yes, plural; Vitti has faces like a sky has clouds—are studies in thinking. As Claudia, she is newly awake and already tired of the dream; as Valentina, poised and merciful; as Vittoria, tentative, alert, a drift that is also a choice. Around her, the men are variations on flight: Sandro flees into appetite, Giovanni into reputation, Piero into liquidity. Jeanne Moreau’s Lidia is the stillest flame in Italian cinema—a candle protected by two hands we cannot see. Alain Delon brings the lethal brightness of youth that confuses speed with direction.

These performers do not “explain” themselves. The trilogy is allergic to psychological footnotes. Motive is legible in movement and proximity: who stands near whom; who turns away; who walks down which corridor and at what pace. Antonioni directs distance the way other directors orchestrate fight scenes.

Time and weather: the films’ secret protagonists

The trilogy reads like a triptych of temporal moods:

- L’Avventura is weathered—wind, rock, sea, the elements scouring away pretense.

- La Notte is nocturnal—reflections, lamp glow, the denatured intimacy of a city after a party.

- L’Eclisse is diurnal to crepuscular—daylight revealing geometry until dusk swallows certainty.

In each, time is not neutral. It performs. You can feel the minutes accruing on faces, the hours abrading desire into habit, the days making markets swell and lovers thin out. When Antonioni lets a shot linger, he is not delaying plot; he is telling the truth about duration: how long it takes for reality to assert itself.

Modern love under pressure: class, money, and mobility

The trilogy isn’t only metaphysical; it’s attuned to class. Parties where nobody can be bored honestly; book signings where fame is a commodity; a stock exchange where risk turns into ritual. These spaces do more than host the characters; they discipline them, offering scripts—flirtation, networking, speculation—that everyone knows and nobody believes. The cost of admission is inattention to one’s own discomfort, which is why Antonioni’s close attention feels, in itself, subversive.

Mobility—cars, boats, planes—appears to expand freedom while actually deracinating the people in motion. (How often does true intimacy occur in these films while someone is moving? Almost never.) The vehicles are efficient at taking people away and nearly useless at taking them toward anything.

Influence: what changed after Antonioni

Without this trilogy, entire regions of modern cinema would look different. You can trace its DNA in:

- The long-take urban alienations of European auteurs from the 1960s to today.

- The American art-film’s embrace of story ellipsis and architectural framing.

- Asian cinemas that refine silence and duration into primary expressive tools—where a bus stop can be a climax and a hallway a biography.

- Countless directors (from the minimalist to the maximalist) who learned that landscape can think and objects can lie.

And the trilogy continues to school us—not in the attributes of a “style,” but in a discipline of looking: hold the shot longer than comfort allows; trust that the wind knows something.

Three close readings: scenes that teach us how to watch

1) The rocks of L’Avventura

When the party explores the island, the wind erases dialogue, forcing us to watch rather than listen. The landscape’s indifference is palpable. When Anna vanishes, the shot doesn’t ratchet up suspense; it flattens it. We wait, scan, fail to decode. In that failure, we experience the film’s thesis: meaning is not guaranteed by narrative setup.

2) The party in La Notte

This long sequence is a laboratory. Music, chatter, flirtation—a full buffet of social signals. And yet Lidia is surrounded by an acoustic loneliness the noise cannot perforate. When Giovanni and Valentina talk at the margins, we feel an intelligence meeting a façade. It’s not lust that binds them; it’s the flattery of being read.

3) The final street montage in L’Eclisse

Those seven minutes are the anti-payoff payoff. The film withholds the couple and offers their absence as content. The images repeat places we know—like ideas we revisit when we can’t sleep—and we realize that the city remembers routes better than it remembers people. The cut to darkness is not a door slamming; it is a light going out in an empty room.

Craft: how the films are built

- Cinematography & Framing

Crisp, patient camera placement that privileges sightlines and depth over coverage. The lens rarely intrudes; it receives. Antonioni’s frames often push the subject toward a margin, a visual ethics that refuses to pretend humans are always the center of their world. - Editing

Not invisible, not flashy—call it philosophical editing. Cuts feel like conclusions to sentences we’ve been silently completing. Ellipses are grammatical: the absent clause is the one that matters. - Sound

Diegetic noise is curated like music: wind, traffic, footsteps, mechanical churn. When scored music arrives, it’s less emotional gasoline than ambient inquiry—a tone that asks us to keep looking. - Performance Direction

Antonioni sands down the actorly. Emotions appear as tides rather than spikes. The result is not monotony but contour—the feeling that small deflections can reset an orbit.

Themes that triangulate across the trilogy

- Incommunicability

Not a failure of vocabulary; a mismatch of frequencies. Lovers talk across a bandwidth that architecture and money jam. - Desire as drift

Affection reassigns itself not by decision but by proximity, fatigue, weather. The heart’s logic is neither moral nor predictable; it is positional. - The world as co-author

Surfaces—rocks, glass, asphalt—write with the director. Landscape composes; the camera reads. People enter these sentences and hope to be the subject. - Time as solvent

Given time, passion dilutes, certainty softens, faces learn to hold two truths at once. Duration doesn’t cure; it clarifies.

Why the trilogy matters now

We live in a moment where communication has never been more abundant and never felt more failed. If Antonioni’s characters were haunted by telephone lines and party circuits, ours are haunted by feeds and pings. The trilogy predicted the exhaustion of constant contact, the way availability can masquerade as intimacy. Watching these films today is not an exercise in nostalgia; it’s a tutorial in noticing the cost of our connections.

They also teach artistic courage. It is astonishing, still, to make a movie that refuses the comforts of causality, that permits the important to appear small, and that trusts the audience enough to sit in a silence that means.

How to watch them (and rewatch them)

- Don’t chase the plot; let the plot come to you, or not.

- Listen to non-speech: weather, room tone, footsteps, traffic, financial clatter.

- Track spaces as if they were characters: the island in L’Avventura, Milan’s glass in La Notte, the EUR in L’Eclisse.

- Watch faces the way you’d watch cloud cover: changes are real even when they refuse names.

- Accept that the most honest endings are open.

A personal coda

When I first saw L’Avventura, I was irritated—like someone who thought they had bought a map and instead received a compass. On the second viewing, the compass began pointing at everything I usually ignore: the wind’s insistence, a corridor’s length, the way a hand hesitates an extra beat before touching a shoulder. By the time I reached L’Eclisse, I knew the films were not withholding; they were respecting me, sparing me the false certainty of a detective story’s culprit or a melodrama’s confession. They handed me a city, a night, a corner where nothing happens—and asked, gently, “Are you sure?”

What makes the Trilogy of Incommunicability indispensable is not its “difficulty,” but its precision. It is not vague; it is exact about ambiguity. It doesn’t preach; it discloses. In three films, Antonioni re-scaled the human: we are smaller than our architectures, messier than our slogans, lonelier than our parties, and yet capable of gestures—like a hand on a shoulder—that salvage us from total eclipse.

If cinema can be a school of attention, these films are graduate seminars. And every time I return to them, I graduate again—only to discover how much more there is to learn from a gust of wind across stone, the glaze of light on glass at night, and a street corner that keeps its appointment even when we don’t.