The Zagreb School of Animated Films represents one of the most distinctive and influential movements in the history of animation. Emerging from Zagreb, Croatia, primarily through the efforts of Zagreb Film, this loose collective of animators redefined the medium during the mid-20th century with a bold, innovative approach that broke away from dominant Western conventions, particularly those of Disney. Coined by French film critic Georges Sadoul in 1959, the term “Zagreb School” encapsulates a style and philosophy that prioritized stylization, satire, and adult-oriented themes over traditional realism and family-friendly narratives. Its legacy endures as a testament to the power of creativity under constraint, influencing animators worldwide and leaving an indelible mark on global film heritage.

Origins and Historical Context

The story of animation in Zagreb begins in 1922 with two short animated commercials crafted by Sergej Tagatz, marking the earliest known ventures into the medium in the region. However, it wasn’t until the post-World War II era that animation gained significant traction in Yugoslavia, then a socialist state navigating its unique position between East and West during the Cold War. The formal establishment of Zagreb Film in 1953 provided the institutional backbone for what would become the Zagreb School, though its animation division didn’t fully coalesce until 1956.

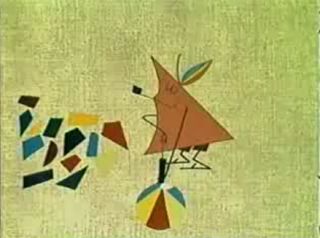

The early years were shaped by a confluence of influences and a rejection of prevailing norms. After the war, Walter Neugebauer’s 1945 film Svi na izbore (Everyone to the Elections) reflected Disney’s polished, realistic style—a stark contrast to what would later define the Zagreb School. By the 1950s, animators like Dušan Vukotić, Vatroslav Mimica, Nikola Kostelac, and Vladimir Kristl began experimenting with new ideas, drawing inspiration from diverse sources. Key among these were Jiří Trnka’s Czech puppet animation The Gift (1947) and the American film The Four Poster (1952), featuring animated sequences by John Hubley of United Productions of America (UPA). UPA’s “reduced animation” style—characterized by minimalist designs, bold graphics, and a focus on ideas over elaborate movement—resonated deeply with the Zagreb animators, who adapted and expanded it into something uniquely their own.

The Golden Age: 1957–1980

The Zagreb School’s “golden age” spanned from 1957 to 1980, unfolding in three distinct waves, each marked by a different cohort of animators. This period saw the group achieve international acclaim, cementing its reputation as a powerhouse of artistic animation.

- First Wave (1957–1962): This initial burst of creativity brought the Zagreb School to the world stage. Vatroslav Mimica’s Samac (Lonely Guy, 1958) won the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival, showcasing a haunting exploration of isolation through stark, modernist visuals. The pinnacle came in 1962 when Dušan Vukotić’s Surogat (Ersatz/The Substitute) won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film—the first non-American work to claim the honor. Surogat, a satirical take on consumerism and human desire, exemplified the school’s signature blend of humor, stylization, and social commentary.

- Second and Third Waves (1960s–1980): Subsequent generations built on this foundation, producing hundreds of shorts that ranged from avant-garde experiments to whimsical narratives. Notable works included Vladimir Kristl’s Don Quixote (1961), a surreal reinterpretation of the classic tale, and Nedeljko Dragić’s Tup-Tup (1972), which earned an Oscar nomination. The school’s output during this time was prolific, with over 500 shorts created, reflecting a diversity of styles and themes united by a commitment to artistic freedom.

The Zagreb School thrived within Yugoslavia’s system of workers’ self-management, which granted artists a degree of autonomy rare in other socialist states. This environment fostered a culture of experimentation, allowing animators to explore universal themes—industrialization, militarism, environmental collapse, and the alienation of the “small man”—rather than adhering to state propaganda.

Defining Characteristics

What set the Zagreb School apart was its rejection of Disney’s “full animation” paradigm, which emphasized realistic movement and broad appeal. Instead, the Zagreb animators embraced “reduced animation,” a term borrowed from UPA but redefined through their lens. This approach relied on simplified designs, limited motion, and a focus on visual storytelling over verbal dialogue, making their films accessible across linguistic barriers.

Joško Marušić, a later contributor to the school, highlighted its commitment to stylization as a counterpoint to Disney’s realism. The Zagreb style was graphic and modernist, often incorporating elements of Suprematism, Surrealism, and abstract art. Films were short—typically 10 minutes or less—and packed with cynicism, self-irony, and existential weight. The recurring motif of the “small man” (mali čovjek)—a powerless figure grappling with modernity—became a hallmark, reflecting both personal and societal struggles.

Unlike the confident “new man” of Soviet animation or the anthropomorphic whimsy of American cartoons, Zagreb’s characters were fallible, their worlds “unperfect” rather than imperfect. Technical flaws, like stray lines or unsynchronized sound, were often left intact, celebrating the handmade nature of the craft. This ethos transformed animation into a “cinema of the laborer,” honoring the artisan behind the work rather than the technology itself.

Key Figures and Works

The Zagreb School’s success rested on the shoulders of its visionary artists:

- Dušan Vukotić: The school’s leading light, Vukotić brought architectural precision and cartoonist wit to films like Surogat and Cow on the Moon (1959). His Oscar win marked a turning point, proving European animation could rival Hollywood.

- Vatroslav Mimica: A former live-action filmmaker, Mimica infused animation with modernist depth. Samac and The Inspector Returns Home (1959) explored loneliness and existential dread through groundbreaking visuals.

- Nikola Kostelac: An architect-turned-animator, Kostelac introduced modernist design principles, influencing the school’s aesthetic foundation.

- Vladimir Kristl: An avant-garde painter, Kristl pushed boundaries with chaotic, philosophical works like Don Quixote, embodying the school’s experimental spirit.

Later contributors like Zlatko Grgić (Professor Balthazar), Nedeljko Dragić, and Milan Blažeković (The Elm-Chanted Forest, 1986) expanded the school’s reach into television and feature films, maintaining its creative ethos.

Importance and Global Impact

The Zagreb School’s importance lies in its radical reinvention of animation as an art form for adults. By shifting focus from fairy tales to contemporary issues, it broadened the medium’s scope and audience. Its “reduction” principle—streamlining animation to emphasize ideas over spectacle—revolutionized production techniques, making high-quality work feasible with limited resources. This approach influenced animators globally, from Eastern Europe to North America.

The school’s international accolades—over 400 awards, including the Oscar—underscored its prestige. The establishment of Animafest Zagreb in 1972, the world’s second-oldest animation festival after Annecy, further solidified its legacy, providing a platform for new talent and preserving its heritage.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

After the golden age, the Zagreb School faced challenges. Yugoslavia’s economic woes in the 1980s and its dissolution in 1991 disrupted production, though Zagreb Film persisted, producing features like Lapitch the Little Shoemaker (1997). The school’s spirit lives on through restoration efforts, with classics like Surogat and Professor Balthazar digitized and shared on platforms like YouTube since the 2000s.

Contemporary animators, such as Daniel Šuljić and Nicole Hewitt, carry forward its tradition of innovation, while academic programs like the University of Zagreb’s Animation and New Media department ensure its principles endure. Scholars like Paul Morton have analyzed its “unperfect” aesthetic, linking it to broader cultural narratives of resilience and humanity.

The Zagreb School’s legacy is multifaceted: it challenged animation’s commercial constraints, elevated its artistic potential, and proved that small, resource-strapped teams could achieve greatness. Its films remain a treasure trove of wit, style, and insight, inviting new generations to rediscover a movement that dared to be different.

Conclusion

The Zagreb School of Animated Films stands as a beacon of creativity and defiance, a movement born from a unique historical moment yet timeless in its appeal. Its importance lies not just in its awards or innovations but in its enduring message: that animation can be a profound, personal, and universal art. As its works continue to be restored and celebrated, the Zagreb School’s legacy inspires animators and audiences alike to embrace the unperfect beauty of the human experience.