Introduction: The Filmmaker Who Turned China Into a Cinematic Canvas

In world cinema, few filmmakers have attained the scale, influence, and international recognition of Zhang Yimou (张艺谋). From the moment he debuted with Red Sorghum in 1988—a culturally explosive masterpiece that announced China’s cinematic reawakening—to the color-saturated wuxia spectacles of Hero and House of Flying Daggers, to the intimate dramas of ordinary rural life in Not One Less and The Road Home, Zhang has built a filmography that is both remarkably diverse and unmistakably his.

He is a director of contrasts:

- intimate yet epic

- politically symbolic yet deeply personal

- visually lush yet emotionally austere

- traditional yet experimental

- loyal to national narratives yet capable of profound critique

Zhang is the central figure of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, a group that reshaped Chinese cinema in the 1980s and 1990s in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Together with Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang, and others, Zhang helped transform China’s film language from state-didactic realism into global arthouse poetry.

Zhang’s cinema is marked by:

- meticulous use of color as psychology and politics

- enigmatic heroines, often played by Gong Li or Zhang Ziyi

- epic storytelling fused with operatic visuals

- ritual-like choreography

- a painter’s precision in framing, texture, and motion

- themes of oppression, defiance, human resilience, and fate

To write about Zhang Yimou is to write about a filmmaker whose images have become inseparable from modern Chinese cultural identity. But it is also to explore a creator in constant negotiation with state power, national expectations, global markets, and his own artistic evolution.

This article examines Zhang’s life, his rise from rural hardship to national icon, his major films and themes, his relationship to Chinese politics, and his enduring global legacy. It is written from the perspective of a cinephile deeply immersed in Chinese cinema and its historical, aesthetic, and ideological complexities.

I. Early Life: Hardship, Discipline, and the Formation of a Visual Poet

Zhang Yimou was born in 1950 in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province—an auspicious birthplace, historically the heart of Chinese civilization but also a region marked by political unpredictability in the mid-20th century.

A Family Marked by Politics

Zhang’s family background was politically “undesirable”:

- His father served as an officer in the Nationalist (Kuomintang) army.

- His grandfather was a wealthy landowner.

During the Maoist era, this lineage placed Zhang’s family under suspicion. His early life coincided with:

- land reform

- class struggle campaigns

- collectivization

- the Great Leap Forward

- the Cultural Revolution

He was sent to rural farms and factories as part of the Rustication Movement. Those difficult years—manual labor, repetitive movements, collective life—left profound marks on his cinematic worldview.

Zhang’s cinema, even decades later, often returns to:

- the body as instrument, pushed to physical limits

- collective movements, resembling factory labor or military choreography

- oppression, both personal and institutional

- resilience, embodied especially in rural women

A Late Start in Film, But a Crucial One

Due to the Cultural Revolution, film schools were closed for a decade. When the Beijing Film Academy reopened in 1978, Zhang applied, submitting photography portfolios created during his years of labor. He was accepted at the age of 27—much older than his peers.

This late start gave him:

- maturity and real-world experience

- a visual sensibility shaped by hardship

- an awareness of political constraints

- a deep connection to China’s rural working class

At the Academy, Zhang formed lifelong collaborations with the emerging Fifth Generation filmmakers. They would graduate in 1982 and set out to redefine Chinese filmmaking.

II. The Rise of the Fifth Generation: Rebirth of Chinese Cinema

The Fifth Generation filmmakers were the first artists educated after the Cultural Revolution. They were determined to reject:

- propagandistic Soviet-style realism

- political didacticism

- formulaic narratives

- lifeless images

Instead, they embraced:

- myth

- folklore

- poetic visual storytelling

- bold color palettes

- fragmented narratives

- rural landscapes

- humanistic themes

Zhang began his career not as a director but as a cinematographer, shooting landmark films like:

- One and Eight (1983)

- Yellow Earth (1984, directed by Chen Kaige)

- The Big Parade (1986)

His cinematography already displayed the traits that would define his directorial career:

- natural light

- painterly compositions

- geometric arrangements of bodies

- landscapes that dwarf human beings

- color as emotional and political coding

Yellow Earth, in particular, is considered one of the great films of the 1980s and a turning point in world cinema. Zhang’s cinematography transformed rural China into a mythic landscape, influencing filmmakers far beyond China’s borders.

By the mid-1980s, Zhang was ready to direct.

III. Red Sorghum (1988): A Bold, Sensual, Earthbound Debut

Red Sorghum launched Zhang Yimou’s directorial career with thunderous force.

A Story Rooted in Soil and Blood

Based on Mo Yan’s novel, the film is an explosion of:

- sensuality

- mythic violence

- rural humor

- agrarian ritual

- national memory

It tells the story of a young woman (Gong Li, in her debut), forced into marriage with a leper wine-maker, and eventually becoming the matriarch of a sorghum winery during the wartime Japanese invasion.

Color as a New Cinematic Language

Red Sorghum introduced Zhang’s iconic visual approach:

- vivid reds of sorghum fields

- golden sunlight on rural workers

- deep earth tones of peasant life

These colors stood in striking contrast to the politically muted palettes of previous decades. Zhang was rewriting visual language itself.

A National Cinematic Myth

The film celebrates rural resilience but refuses to romanticize suffering. It is sensual, almost pagan, filled with laughter, blood, and primal energy.

It won the Golden Bear at Berlin, cementing Zhang’s status as a major new global auteur.

IV. The Gong Li Era: An Iconic Collaboration Transcending Cinema

From Red Sorghum onward, Gong Li became Zhang’s muse, collaborator, and artistic equal. Their partnership, spanning nearly a decade, produced some of the finest films in modern East Asian cinema. Together, they crafted a gallery of women whose:

- strength

- intelligence

- suffering

- agency

…embodied the complex reality of Chinese womanhood across history.

Their films include:

- Ju Dou (1990)

- Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

- The Story of Qiu Ju (1992)

- To Live (1994)

- Shanghai Triad (1995)

Gong Li’s Presence

Gong Li’s power comes from:

- controlled emotional expression

- expressive eyes

- ability to embody resilience

- elegance mixed with defiance

- classical beauty combined with modern awareness

She plays women who are:

- oppressed, but never broken

- silenced, but never voiceless

- constrained, but capable of awakening agency

Zhang’s Gong Li era is arguably one of the greatest director–actress partnerships in world cinema, comparable to Antonioni–Vitti, Bergman–Ullmann, or Wong Kar-wai–Maggie Cheung.

V. Raise the Red Lantern (1991): A Masterpiece of Spatial Oppression

This film remains one of the towering achievements of global cinema.

The Setting

A wealthy Republican-era household where a master has four wives, each installed in isolated courtyards. Red lanterns are lit outside the chosen woman’s chamber at night.

The lanterns symbolize:

- favoritism

- power

- sexual hierarchy

- emotional manipulation

Architecture as Prison

The courtyard house is filmed with geometric precision:

- symmetrical framing

- rigid vertical lines

- repetitive pathways

- oppressive spatial logic

The walls become psychological barriers.

Color as Emotional Code

Red becomes:

- desire

- cruelty

- control

- ritual

The blue-gray stone walls suggest:

- coldness

- tradition

- confinement

A Film About Power, Not Just Gender

Though the story revolves around concubines, it is truly about:

- authoritarian systems

- cycles of oppression

- internalized hierarchy

- emotional survival

It is a critique of:

- patriarchy

- feudal structures

- the machinery of submission

The film was internationally hailed but met censorship resistance at home.

VI. To Live (1994): Zhang’s Humanist Masterpiece

To Live is widely considered Zhang Yimou’s most profound and universal film. Based on Yu Hua’s novel, it chronicles several decades of Chinese history through one ordinary family’s suffering and endurance.

A Rare Achievement in Political Cinema

The film spans:

- The Chinese Civil War

- Land reform

- The Great Leap Forward

- Famine

- The Cultural Revolution

But the film never preaches. It focuses on:

- human resilience

- familial bonds

- tragic absurdities of politics

- how ordinary people survive forces beyond their control

Fugui and Jiazhen: Icons of Chinese Humanity

Ge You and Gong Li embody characters who:

- lose everything

- suffer unimaginable tragedy

- yet retain dignity, humor, and love

Their endurance becomes a quiet act of resistance.

Banned in China

Despite international acclaim, the film was banned in China for over a decade. Zhang and Gong Li faced temporary bans on filmmaking. The government found the film’s depiction of historical trauma “too negative.”

This placed Zhang in a complicated relationship with the state—something that would shape his later turn toward large-scale patriotic spectacles.

VII. The Naturalism Phase: Rural Neorealism and Emotional Purity

Following political pressures, Zhang shifted toward smaller, intimate dramas that focused on rural life, avoiding political provocations.

Key films:

Not One Less (1999)

A young substitute teacher tries to keep her students from dropping out. Non-professional actors give the film a documentary-like authenticity.

The Road Home (1999)

A sentimental, beautifully photographed love story featuring a young Zhang Ziyi. The film is gentle, heartfelt, and nostalgic.

Happy Times (2000)

A tragicomedy about poverty, deception, and dignity. It balances humor with emotional depth.

These works reaffirmed Zhang’s ability to portray:

- rural hardship

- human kindness

- delicate emotions

- characters defined by simplicity rather than grandeur

They also paved the way for a new phase: Zhang’s epic reimagining of wuxia.

VIII. Hero (2002): Rebirth Through Color and Spectacle

With Hero, Zhang Yimou reinvented himself once again.

A Visual Symphony

The film uses color chapters—red, blue, white, green—to convey:

- shifting emotions

- alternative perspectives

- political truths

- philosophical contrasts

It stars Jet Li, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, Donnie Yen, and Zhang Ziyi—assembling some of Asia’s greatest actors into one operatic narrative.

Politics and Controversy

Hero tells the story of assassins confronting the First Emperor of China. Its ending, which suggests that unity under authoritarian rule can be justified to avoid chaos, sparked debates:

- Is Zhang advocating centralized power?

- Is the film reading modern Chinese legitimacy into ancient history?

- Or is it a commentary on sacrifice and the tragic cost of peace?

Regardless, it became a landmark in Chinese blockbuster cinema.

IX. House of Flying Daggers (2004): Sensuality, Nature, and Tragic Love

This film embraced:

- sweeping landscapes

- balletic martial-arts choreography

- tragic romance

- poetic visual textures

Zhang moved away from political allegory toward emotional extravagance.

Zhang Ziyi’s Iconic Role

Zhang Ziyi’s performance combines:

- fragility

- seduction

- physical grace

- emotional fire

The bamboo forest sequence remains one of the great action set-pieces of the 21st century.

X. Curse of the Golden Flower (2006): Operatic Decadence and Court Intrigue

One of Zhang’s most visually maximalist works, this Tang Dynasty epic features:

- lavish gold interiors

- violent family politics

- catastrophic rebellion

- opulent costumes

It is Shakespearean tragedy reimagined as imperial melodrama.

XI. The Later Period: Nation, Spectacle, and Experimentation

The Flowers of War (2011)

Set during the Nanjing Massacre, starring Christian Bale, exploring heroism, trauma, and sacrifice.

Coming Home (2014)

A return to intimate drama about love devastated by the Cultural Revolution. Gong Li gives one of her finest performances.

Shadow (2018)

A monochromatic wuxia film inspired by ink-wash painting. Zhang’s most experimental visual work in decades.

Cliff Walkers (2021)

A spy thriller set during the Japanese occupation. Stylish, snowy, suspenseful.

Full River Red (2023)

A high-energy, theatrical historical comedy-thriller, showing Zhang’s late-career playfulness.

XII. Artistic Themes: What Defines Zhang Yimou’s Cinema?

1. Color as Emotion and Ideology

Red = passion, violence, power

Blue = melancholy, truth

Green = purity, possibility

Gold = decadence, corruption

2. Women as Moral Centers

His heroines often embody resistance, endurance, intelligence.

3. Ritual and Repetition

Ceremonies, processions, lanterns, fabrics—cinema as choreography.

4. Oppression and Power

Whether feudal, familial, or political, authority is a recurring antagonist.

5. Fate and Tragedy

Many Zhang films end in inevitability.

6. Landscapes as Characters

Sorghum fields, bamboo forests, deserts, snow—nature mirrors the emotional world.

7. The Tension Between Individual and State

Zhang navigates this carefully but never ignores it.

XIII. Zhang Yimou and the Chinese State: A Complex Relationship

Zhang has been:

- censored

- banned

- criticized

- celebrated

- commissioned

- rewarded

He directed:

- the 2008 Beijing Olympics Opening Ceremony, regarded as the greatest in Olympic history

- the 2022 Winter Olympics ceremonies

- major state-backed films

Some view this as ideological alignment. Others see it as an artist negotiating survival and creative opportunity within China’s cultural landscape.

In truth, Zhang is neither dissident nor propagandist. He is an artist navigating a system where filmmaking is inseparable from state context.

XIV. Legacy: Zhang Yimou’s Impact on Global Cinema

International Recognition

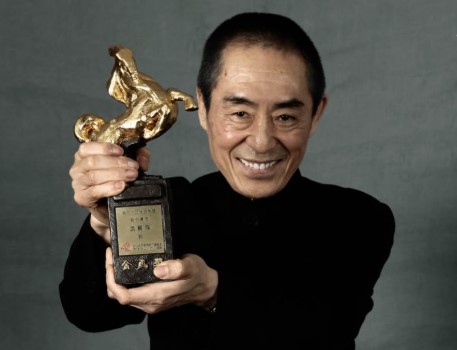

- Three-time Oscar nominee

- Golden Lion winner

- Golden Bear winner

- Inspired directors from South Korea to Hollywood

- Helped popularize Chinese wuxia worldwide

Influence on Chinese Cinema

- paved the way for commercial blockbusters

- elevated Chinese actresses to global fame

- set visual standards unmatched in Asia

- demonstrated the artistic power of color, choreography, and emotion

Cultural Significance

Zhang’s imagery has become part of China’s cultural identity in the late 20th and early 21st centuries—shaping how China sees itself and how the world sees China.

Conclusion: The Cinema of a Visual Poet in Constant Reinvention

Zhang Yimou’s cinema is a journey across:

- Chinese history

- political systems

- rural hardship

- imperial opulence

- mythic landscapes

- intimate heartbreak

- national spectacle

He is an artist of contradictions: rebellious yet loyal, intimate yet epic, traditional yet experimental. Through all phases, one thing remains constant: Zhang Yimou is a painter of human resilience, and his films, at their best, reveal the emotional and historical heartbeat of China.

His work reminds us that cinema is both art and survival, beauty and struggle—light projected onto screens, and memory projected onto nations.

Zhang Yimou will remain, alongside Ozu, Kurosawa, Wong Kar-wai, and Ang Lee, one of the defining voices of East Asian cinema—an artist whose images endure long after the final frame fades to black.

Pingback: Chen Kaige: The Poet of Paradox — Cinema, History, and Transformation in the Fifth Generation - deepkino.com