The 1910s and 1920s stand as the most formative decades in film history — a time when cinema stopped being a novelty and became an art. The world, still reeling from industrial transformation and global war, found in moving images a new language for dreams, fears, and ideals. This era, often called the Silent Revolution, produced visual storytelling so sophisticated that even today, filmmakers borrow its grammar.

The United States, Germany, the Soviet Union, France, and Sweden each developed distinct cinematic voices, collectively defining what film could be. From the psychological shadows of German Expressionism to the rhythmic dynamism of Soviet Montage, from Hollywood’s narrative perfection to the poetic austerity of Swedish cinema, the silent period remains one of the most productive and creatively fertile eras in global film history.

1. The American Foundations: From Spectacle to Storytelling

Before cinema became art, it was entertainment — a fairground attraction, a novelty of flickering light. By the 1910s, however, American filmmakers began transforming the motion picture into a storytelling medium. The key figure in this transformation was D. W. Griffith, whose films expanded the possibilities of editing, close-ups, and crosscutting.

Griffith and the Birth of Narrative Cinema

With The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916), Griffith codified the language of cinematic storytelling — though the former’s racist ideology rightfully taints its legacy, its technical innovation remains undeniable. He orchestrated large-scale battle scenes, parallel narratives, and emotional close-ups that gave cinema its emotional depth. Griffith didn’t invent these techniques, but he synthesized them into a coherent system that directors around the world adopted.

Intolerance in particular became a blueprint for epic structure. Spanning four different historical periods, it pioneered complex cross-cutting — linking stories across time and space through thematic rhythm rather than plot continuity. In doing so, Griffith established the director as a “composer of images,” a role that would define the auteur theory decades later.

The Studio System and the Rise of Genres

While Griffith set the language, Hollywood’s industrial machinery refined it. The 1910s and 1920s saw the emergence of genre cinema — westerns, comedies, melodramas, and serials. Directors like Cecil B. DeMille, King Vidor, and Erich von Stroheim crafted ambitious spectacles that merged art with commerce.

Meanwhile, comedians like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd brought humanity to slapstick. Chaplin’s The Kid (1921) fused comedy with sentiment, showing that silent film could convey profound emotion without dialogue. Keaton’s The General (1926) demonstrated precision in timing and composition that remains unmatched.

The American Legacy

By the late 1920s, Hollywood had established an industrial and artistic model that dominated global cinema. Its emphasis on narrative clarity, visual coherence, and emotional universality would define the “classical style” — still the foundation of mainstream filmmaking today. Yet while America standardized cinematic language, Europe was busy reinventing it.

2. German Expressionism: Shadows, Madness, and Modern Anxiety

No national cinema of the silent era captured the turmoil of its society as vividly as Weimar Germany. Emerging after World War I, German Expressionism translated collective trauma and social instability into distorted worlds of light and shadow.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and the Expressionist Aesthetic

Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari stands as a landmark — a film where set design becomes psychology. Its twisted, painted backdrops reflected the chaos of the human mind and the fractured German psyche after war. The story of a manipulative doctor and his somnambulist servant mirrors authoritarian control and collective submission, making it one of the first truly political films.

The visual style — sharp angles, exaggerated shadows, and disorienting architecture — turned cinema into a subjective medium. Rather than showing reality, Expressionism externalized emotion.

From Caligari to Murnau and Lang

Directors F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang pushed Expressionism into more refined visual territory. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) reimagined the vampire myth as an allegory of plague and death, filmed with haunting natural light and eerie realism. His later masterpiece, The Last Laugh (1924), told an entire story with almost no intertitles, relying solely on visuals and the expressive power of actor Emil Jannings. The moving camera — a technical breakthrough at the time — mirrored the protagonist’s descent from dignity to despair.

Lang’s Metropolis (1927) represented Expressionism’s grand finale. A monumental fusion of architecture, myth, and futurism, it depicted a mechanized dystopia that still influences science-fiction cinema. Its cityscapes, miniatures, and class conflict imagery shaped the visual identity of countless later films — from Blade Runner to The Matrix.

Expressionism’s Influence

Expressionism proved that cinema could visualize the inner life — dreams, madness, anxiety — through design and cinematography. It established the power of lighting, composition, and abstraction as storytelling tools, a legacy carried forward by film noir, horror, and even modern psychological dramas.

3. The Soviet Montage Revolution: Editing as Thought

If Germany turned images into psychology, the Soviet filmmakers transformed editing into philosophy. Following the 1917 Revolution, cinema became an instrument of ideology and education — but also an experimental art form.

Kuleshov and the Birth of Montage Theory

Lev Kuleshov’s experiments in the early 1920s revealed how meaning in cinema arises from the juxtaposition of shots. The famous “Kuleshov Effect” demonstrated that audiences derive emotion and narrative not from individual images but from their combination. This discovery laid the foundation for the theory of montage — editing as the essence of cinema.

Eisenstein and the Art of Conflict

Sergei Eisenstein expanded montage into a revolutionary weapon. His Battleship Potemkin (1925) remains one of the most analyzed films ever made. The Odessa Steps sequence — with its rhythmic cutting and shocking violence — exemplifies “montage of attractions,” where each cut collides with the next to create emotional and intellectual impact.

In Eisenstein’s hands, editing became dialectical: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. Cinema could now think. Films like Strike (1925) and October (1928) transformed political struggle into visual symphony.

Vertov and the Machine Eye

At the same time, Dziga Vertov developed a different approach. His Man with a Movie Camera (1929) rejected fiction entirely, embracing cinema as a self-aware machine. Vertov’s rapid editing and documentary realism celebrated modern life, the urban rhythm, and the act of filmmaking itself. His notion of the “Kino-Eye” — the camera as an extension of human perception — prefigured avant-garde and experimental cinema.

Legacy of the Soviet Revolution

The Soviet school taught filmmakers that cinema is not mere representation but construction — an art of rhythm, time, and emotion. From Hitchcock’s suspense editing to modern music videos, the grammar of montage remains one of cinema’s greatest gifts from the 1920s.

4. French Experiments: From Impressionism to Poetic Realism

While Germany and the USSR turned inward and ideological, France pursued lyricism and emotion. French filmmakers of the 1910s and 1920s approached cinema as visual poetry — an exploration of perception, mood, and psychological nuance.

French Impressionism and Visual Emotion

Directors like Abel Gance, Germaine Dulac, Louis Delluc, and Jean Epstein sought to express inner states through light, movement, and rhythm. In Gance’s La Roue (1923) and Napoléon (1927), rapid montage and mobile cameras conveyed emotion more than plot. Gance’s use of split screens and wide lenses anticipated the innovations of later decades.

Dulac’s The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) offered one of cinema’s first feminist portraits, using visual symbolism to depict a woman’s psychological imprisonment. Epstein’s Coeur fidèle (1923) and The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) explored subjectivity through slow motion and surreal lighting.

Surrealism and Avant-Garde Radicalism

The late 1920s saw film merge with Surrealism. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) shocked audiences with its dream logic and violent imagery — a deliberate attack on rational narrative. French cinema became a laboratory of visual experimentation, influencing the future cinéma vérité, New Wave, and art cinema traditions.

The Birth of Poetic Realism

Although “poetic realism” would flourish in the 1930s, its roots lie in these silent experiments. The blend of lyric imagery and emotional realism — later seen in Renoir and Carné — began with the Impressionists’ belief that cinema could be both expressive and humanistic.

5. The Nordic Soul: Sweden’s Silent Art

Far from Hollywood and Berlin, Sweden produced one of the most profound and spiritual cinemas of the silent age. Directors like Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller created films that merged natural landscapes with moral introspection, forming a quiet counterpoint to the industrial chaos of modern Europe.

Victor Sjöström: The Poet of Nature and Conscience

Sjöström’s films such as Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), and especially Körkarlen (The Phantom Carriage, 1921) reflect deep humanism and metaphysical awareness. His visual style emphasized real locations, natural light, and the moral struggle between sin and redemption.

The Phantom Carriage, often called Sweden’s greatest silent film, employed double exposures and complex flashbacks to weave a haunting story about death and repentance. Its narrative sophistication prefigured later psychological cinema — most notably Ingmar Bergman, who would cast Sjöström in Wild Strawberries (1957) as a symbolic passing of the torch.

Mauritz Stiller and Greta Garbo

Stiller’s Gösta Berlings Saga (1924) launched the career of Greta Garbo, symbolizing Sweden’s bridge to international cinema. His direction emphasized atmosphere and sensuality, blending myth and realism.

Spiritual Cinema and Natural Landscapes

Swedish silent cinema treated nature as a moral force — forests, seas, and skies mirrored inner emotions. This approach influenced world cinema’s later fascination with environment and existential themes, from Tarkovsky to Malick.

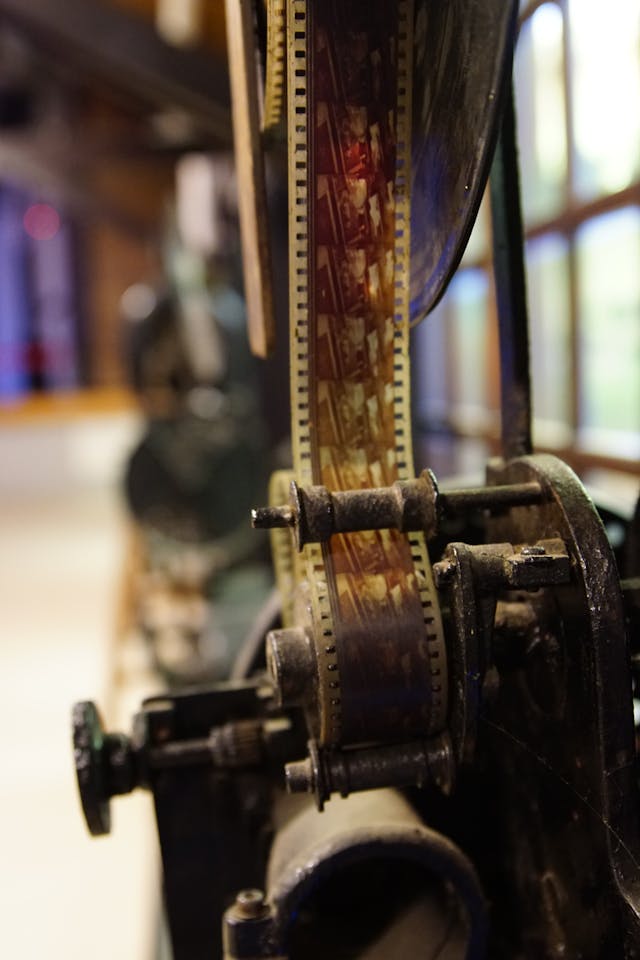

6. Technical Innovations and Global Exchange

The silent era was not only artistic but profoundly technical. Innovations in lighting, lenses, and camera mobility reshaped film’s visual potential.

- Cinematography: The use of soft focus, deep staging, and expressive lighting evolved rapidly. Cinematographers like Karl Freund (who later worked on Metropolis and Hollywood horrors) pioneered moving cameras and fluid tracking shots.

- Set Design: German studios like UFA became architectural workshops for imagination.

- Editing: Soviet experiments spread internationally, influencing American editors.

- Acting: Performers learned to convey subtle emotion through gesture rather than exaggeration, refining the visual expressiveness of cinema.

The silent era was global in spirit — filmmakers watched each other’s work, borrowed ideas, and expanded the language together. By the late 1920s, cinema had matured into a universal art capable of expressing every human emotion without a single spoken word.

7. The Transition to Sound: The End of an Era

When synchronized sound arrived around 1927 with The Jazz Singer, it transformed the industry overnight. But many silent masters viewed the transition with skepticism. For them, silence was not a limitation but a purity — a language of images and rhythm that sound might corrupt.

Indeed, early sound films often felt static, confined by microphones and dialogue. It took years for directors to rediscover the visual dynamism of the silent era. Yet the foundations remained: the grammar of framing, cutting, and visual storytelling continued to guide cinema even in the talkie age.

As the 1930s dawned, silent film’s visual intelligence merged with sound’s emotional immediacy — giving birth to the classical cinema we still celebrate.

8. Legacy: The Eternal Language of Silence

The so-called “silent” era was never truly silent — it spoke with images more eloquent than words. The filmmakers of the 1910s and 1920s invented every major technique modern cinema relies upon: montage, mise-en-scène, camera movement, close-up, flashback, cross-cutting, visual symbolism.

Influence Across Decades

- Film noir borrowed Expressionist lighting.

- New Hollywood revived the moral ambiguity of Swedish realism.

- Music videos and modern editing owe everything to Soviet montage.

- Art cinema from Bergman to Tarkovsky to Béla Tarr draws from the spiritual minimalism of the silent frame.

Even digital-era auteurs — Christopher Nolan, Guillermo del Toro, Bong Joon-ho — often reference silent cinema in their visual storytelling.

Why the Silent Era Still Matters

To watch a silent film today is to return to the origins of visual thought. It reminds us that cinema is not dependent on dialogue but on composition, rhythm, and emotion. These films distilled storytelling to its essence, proving that a moving image could convey the full complexity of human experience.

The Silent Revolution was not merely a historical phase — it was cinema’s first act of consciousness, its discovery of itself as art. Every frame shot since then is, in some way, a continuation of that revelation.