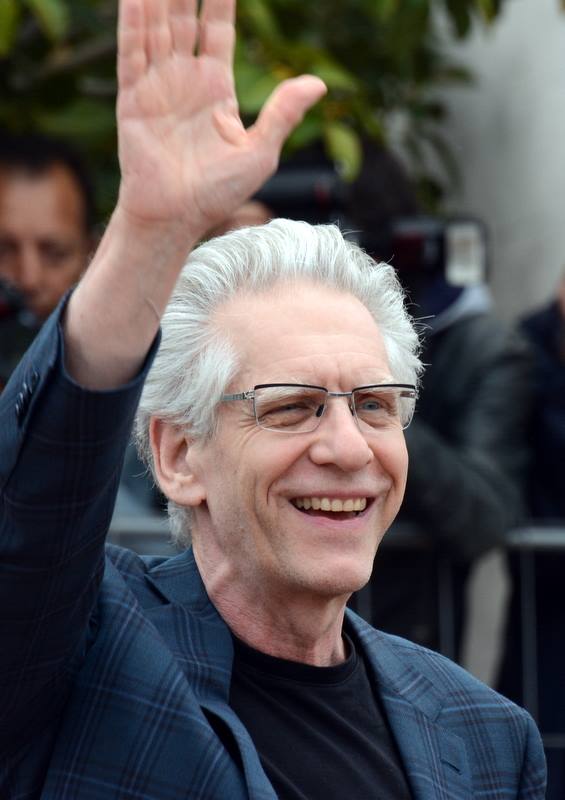

In the landscape of contemporary cinema, few directors have carved out territories as distinct and unsettling as David Cronenberg. The Canadian filmmaker has spent over five decades exploring the fraught boundaries between technology and humanity, mind and body, reality and hallucination. With unflinching camera work and a philosophical bent that never sacrifices emotional impact, Cronenberg has established himself as one of the most original and thought-provoking auteurs in film history. This article examines the remarkable career of David Cronenberg, from his early experimental films to his later mainstream successes, exploring the themes, techniques, and visual language that define his unique contribution to cinema.

The Early Years: Building a Vision

David Paul Cronenberg was born on March 15, 1943, in Toronto, Canada, to a middle-class Jewish family. His father was a writer and editor, while his mother was a pianist. This intellectually stimulating household fostered Cronenberg’s early interest in literature, science, and the arts. He initially pursued a degree in biochemistry at the University of Toronto before switching to English literature, a dual interest in science and art that would come to define his filmmaking career.

Unlike many renowned directors who attended film school, Cronenberg was largely self-taught. His earliest forays into filmmaking came in the late 1960s, when the emerging accessibility of 16mm equipment gave rise to independent cinema. His first shorts, “Transfer” (1966) and “From the Drain” (1967), already displayed his fascination with bodily transformation and psychological disturbance, themes that would become hallmarks of his later work.

In 1969, Cronenberg directed his first feature-length film, “Stereo,” followed by “Crimes of the Future” in 1970. Both were experimental, dialogue-free works that demonstrated his growing interest in the intersection of science, psychology, and sexuality. Shot in stark black and white with clinical precision, these early films captured the sterility of institutional settings while exploring radical scientific experiments on human subjects. Though limited in budget and scope, they established Cronenberg as a filmmaker with a unique vision—one concerned with the contamination of the body and mind by external forces.

Body Horror: The Cronenbergian Aesthetic

The term “body horror” has become inextricably linked with Cronenberg’s name, though the filmmaker himself has expressed ambivalence about the label. Nonetheless, his explorations of physical transformation, disease, and bodily invasion have defined a subgenre that continues to influence horror and science fiction. Cronenberg’s particular brand of body horror is characterized by its unflinching gaze at physical metamorphosis, often rendered with special effects that are simultaneously repulsive and mesmerizing.

In “Shivers” (1975), his first commercial feature, residents of a luxury apartment complex are infected by parasites that transform them into sex-crazed maniacs. The film established several recurring Cronenbergian motifs: isolated communities, scientific experimentation gone awry, and sexuality as both destructive and transformative. Its shocking imagery and explicit content sparked controversy in Canada, where politicians questioned why public funds had supported such “degenerate” art.

Cronenberg refined his approach to body horror in “Rabid” (1977), which starred adult film actress Marilyn Chambers as a woman who develops a vampiric appendage in her armpit following experimental plastic surgery. The film further explored themes of contagion and physical mutation while adding layers of social commentary on medical ethics and consumer culture.

By the time of “The Brood” (1979), Cronenberg was integrating more personal elements into his work. The film—in which a disturbed woman’s rage physically manifests as murderous childlike creatures—was informed by his own painful divorce and custody battle. This merging of emotional trauma with physical horror would become a defining characteristic of Cronenberg’s approach, elevating his films beyond mere shock value to psychological depth.

The pinnacle of Cronenberg’s body horror period arrived with “Scanners” (1981) and “Videodrome” (1983). The former, with its iconic exploding head sequence, explored telepathic powers as both gift and disease. “Videodrome,” meanwhile, stands as perhaps his most complete statement on media, technology, and physical transformation. The film follows a television programmer (James Woods) who discovers a mysterious broadcast signal that causes hallucinations and eventually bodily mutation. With its tagline “Long live the new flesh,” “Videodrome” crystallized Cronenberg’s vision of technology as an evolutionary force that fundamentally alters human biology.

The Fly: Commercial Breakthrough

While Cronenberg had built a devoted cult following with his early horror films, it was “The Fly” (1986) that brought him widespread commercial success and critical acclaim. A reimagining of the 1958 science fiction classic, Cronenberg’s version starred Jeff Goldblum as Seth Brundle, a brilliant scientist whose teleportation experiment goes catastrophically wrong when his DNA merges with that of a housefly.

“The Fly” represents the perfect fusion of Cronenberg’s artistic preoccupations with Hollywood production values. The film’s special effects, which earned an Academy Award, allowed for a detailed and grotesque portrayal of Brundle’s gradual transformation. Yet beneath the horror elements lies a profound meditation on mortality, disease, and love. Many critics have interpreted the film as an allegory for AIDS and terminal illness, though Cronenberg has maintained that such specific readings came after the fact.

What distinguishes “The Fly” from standard horror fare is its emotional core. The relationship between Brundle and journalist Veronica Quaife (Geena Davis) grounds the fantastical premise in human drama. As Brundle’s body deteriorates, the film becomes an achingly sad love story and a meditation on the limitations of human connection in the face of physical decay. This emotional depth, combined with Goldblum’s tour-de-force performance, elevated “The Fly” to the status of a modern classic that transcends genre limitations.

The commercial success of “The Fly” afforded Cronenberg greater freedom in his subsequent projects, allowing him to further develop his distinctive vision while working with larger budgets and more prominent actors. It marked a turning point in his career, demonstrating that his unique sensibility could resonate with mainstream audiences when paired with accessible narratives.

Literary Adaptations: Expanding the Canvas

Following “The Fly,” Cronenberg increasingly turned to literary adaptations that allowed him to explore his thematic obsessions in new contexts. Rather than simply translating books to screen, Cronenberg approached these adaptations as opportunities to find cinematic equivalents for literary techniques, often tackling works considered “unfilmable.”

His adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ fragmentary, hallucinatory novel “Naked Lunch” (1991) stands as perhaps his most audacious undertaking. Rather than attempting a straightforward adaptation of the non-linear text, Cronenberg created a surreal fusion of Burroughs’ biography and fiction. The film follows writer Bill Lee (Peter Weller) as he descends into a drug-induced alternate reality populated by talking insectoid typewriters and sinister conspiracies. Shot with a strange, detached beauty by cinematographer Peter Suschitzky, “Naked Lunch” represented Cronenberg’s most experimental mainstream film, polarizing audiences but securing his reputation as a fearlessly original filmmaker.

“Crash” (1996), adapted from J.G. Ballard’s controversial novel, further pushed boundaries with its exploration of a subculture sexually aroused by car accidents. The film’s clinical depiction of the intersection between technology, violence, and eroticism provoked intense reactions, with some critics praising its cold brilliance while others condemned it as pornographic. Despite—or perhaps because of—the controversy, “Crash” won a Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival “for originality, for daring, and for audacity.”

With “eXistenZ” (1999), Cronenberg returned to original material while synthesizing many of his recurring themes. The film, which follows game designer Allegra Geller (Jennifer Jason Leigh) as she tests a virtual reality system that connects directly to players’ bodies, revisited questions of technology and physical transformation while adding layers of philosophical inquiry about the nature of reality. Coming in the same year as “The Matrix,” “eXistenZ” offered a more visceral, biological vision of virtual reality that has proven remarkably prescient in its concerns about the blurring boundaries between technology and human identity.

A New Direction: Psychological Dramas

The turn of the millennium saw Cronenberg evolve beyond his reputation as a horror director, embracing psychological dramas that maintained his thematic interests while largely abandoning fantastic elements. This phase of his career has been marked by critical acclaim and collaboration with major stars, demonstrating his versatility as a filmmaker.

“Spider” (2002), adapted from Patrick McGrath’s novel, follows a mentally ill man (Ralph Fiennes) as he attempts to piece together traumatic childhood memories after being released from an institution. Shot with austere precision and featuring a remarkable, nearly wordless performance from Fiennes, the film explored the fragility of memory and identity without resorting to the physical transformations of Cronenberg’s earlier work.

His fruitful collaboration with actor Viggo Mortensen began with “A History of Violence” (2005), based on a graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke. The film, which received two Academy Award nominations, follows a small-town family man whose heroic actions expose a violent past he had tried to escape. With its exploration of identity, the inescapability of the past, and the human capacity for violence, the film maintained Cronenberg’s thematic concerns while wrapping them in a more accessible narrative.

Cronenberg and Mortensen reunited for “Eastern Promises” (2007), a crime thriller set in London’s Russian mafia underworld. The film’s unflinching portrayal of violence—most famously in a brutal bathhouse fight scene featuring a naked Mortensen—demonstrated Cronenberg’s continued willingness to push boundaries. Yet the film also revealed a newfound interest in cultural identity and displacement, themes that would recur in his later work.

“A Dangerous Method” (2011) marked perhaps the greatest departure from Cronenberg’s earlier style. The historical drama explored the relationship between psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud (Mortensen) and Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender), and their patient Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley). Though lacking the visual shock value of his horror films, the film’s focus on sexual repression, psychological transformation, and the mind-body relationship demonstrated a clear continuity with Cronenberg’s longstanding preoccupations.

With “Cosmopolis” (2012), adapted from Don DeLillo’s novel, Cronenberg returned to more experimental territory. Set almost entirely in a billionaire’s limousine as it crawls across Manhattan during a financial crisis, the film starred Robert Pattinson as a disconnected financial prodigy watching his fortune evaporate. The film’s clinical detachment and focus on technology’s dehumanizing effects recalled earlier Cronenberg works while addressing contemporary concerns about capitalism and alienation.

“Maps to the Stars” (2014), a savage satire of Hollywood, featured Julianne Moore in a Cannes Best Actress-winning role as an aging actress desperate to play the part originated by her mother. The film’s exploration of incest, abuse, and celebrity culture represented some of Cronenberg’s most acidic social commentary, suggesting that his edge had not dulled with age.

After an eight-year hiatus from feature filmmaking, Cronenberg returned with “Crimes of the Future” (2022), a science fiction body horror film that in many ways represented a return to his roots. Set in a future where humans have begun spontaneously evolving new organs, the film starred Viggo Mortensen as a performance artist who publicly showcases the removal of these organs. Despite its futuristic setting, the film connected directly to Cronenberg’s earliest preoccupations with bodily transformation and the aesthetic potential of mutation.

Themes and Motifs: The Cronenberg Universe

Throughout his varied career, certain themes and motifs have consistently appeared in Cronenberg’s work, creating a coherent artistic vision despite his evolution as a filmmaker.

The Body as Battleground

The most obvious recurring element in Cronenberg’s filmography is his preoccupation with the human body as a site of transformation, conflict, and revelation. From the parasites of “Shivers” to the technological infections of “Videodrome” and the genetic splicing of “The Fly,” Cronenberg repeatedly portrays the body as unstable and vulnerable to outside forces. Yet these invasions are rarely presented as simply destructive—they often represent evolutionary adaptations or necessary, if painful, transformations.

In his later, more realistic films, this bodily focus shifts to scars, tattoos, and wounds that tell stories about identity and history. The elaborate tattoos that cover Viggo Mortensen’s body in “Eastern Promises,” for instance, function as a biographical text that reveals his character’s history in the Russian criminal underworld.

Technology and Evolution

Cronenberg has consistently explored how technology alters human consciousness and physicality. Far from presenting a simplistic technophobia, his films often suggest that technological change is an inevitable part of human evolution, albeit one that comes with profound risks and discomforts.

In “Videodrome,” television signals physically transform the viewer’s body. In “eXistenZ,” gaming technology fuses directly with human nervous systems. Even in “Crash,” automotive technology creates new possibilities for human sexuality and connection, however disturbing those possibilities might be. This view of technology as an evolutionary force rather than simply an external tool distinguishes Cronenberg’s work from more conventional science fiction.

Duality and Identity

Questions of duality and divided identity recur throughout Cronenberg’s filmography. From the twin gynecologists of “Dead Ringers” to the dual identities in “A History of Violence,” his characters often struggle with fragmented or competing versions of themselves. This preoccupation connects to larger philosophical questions about the nature of consciousness and the stability of personal identity.

“The Fly” provides perhaps the clearest example of this theme, as Seth Brundle gradually realizes that he is becoming neither fully human nor fully insect, but something new and terrifying. His famous line—”I’m an insect who dreamed he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over and the insect is awake”—captures the existential horror of identity dissolution that permeates Cronenberg’s work.

Sexuality and Transgression

Sexuality in Cronenberg’s films is rarely straightforward or conventional. Instead, it frequently involves transgression, mutation, or fusion with technology. From the parasitic sexuality of “Shivers” to the car-crash fetishism of “Crash,” Cronenberg portrays sexual desire as a potentially disruptive force that breaks through social norms and even biological limitations.

Yet these transgressive sexual elements are not simply presented for shock value. They often represent attempts to transcend physical limitations or forge new forms of connection. In “Dead Ringers,” the twin gynecologists’ shared sexual experiences constitute an attempt to overcome their fundamental separation. In “The Fly,” Seth and Veronica’s lovemaking takes on new significance as his body begins to transform, representing both a final connection before separation and a potential transmission of his mutation.

Isolated Communities and Secret Societies

Many of Cronenberg’s films feature isolated communities or secret societies with their own rules and rituals. The luxury apartment complex in “Shivers,” the telepathic “scanners” in the film of the same name, the car-crash enthusiasts in “Crash,” and the Russian criminal organization in “Eastern Promises” all represent closed worlds with specialized knowledge and practices hidden from mainstream society.

These isolated groups often serve as microcosms that allow Cronenberg to explore social dynamics and transformative processes in controlled environments. They also reflect his interest in subcultures that develop their own languages, rituals, and values in response to shared experiences or abilities.

Visual Style: The Cronenberg Aesthetic

Cronenberg’s visual style has evolved throughout his career, yet certain consistent elements create a recognizable aesthetic that supports his thematic concerns.

Clinical Precision

Even in his most fantastical films, Cronenberg often employs a detached, clinical visual approach that presents bizarre or disturbing content with documentary-like precision. This technique, sometimes called “medical realism,” creates cognitive dissonance by treating the extraordinary as matter-of-fact. In “Dead Ringers,” for instance, the gynecological instruments designed by the increasingly deranged Mantle twins are presented with the same visual clarity as standard medical equipment, making their strangeness all the more disturbing.

This clinical approach extends to Cronenberg’s frequent use of symmetrical compositions and measured camera movements. Rather than employing disorienting techniques to convey psychological disturbance, he often prefers to present disturbing content in visually ordered frames, creating tension between formal control and chaotic subject matter.

Body Transformation Effects

Throughout his career, Cronenberg has pushed the boundaries of special effects to realize his visions of bodily transformation. Working with makeup and effects artists like Chris Walas and Stefan Dupuis, he has created some of cinema’s most memorable physical metamorphoses. The exploding head in “Scanners,” Brundlefly’s deterioration in “The Fly,” and the fleshy video game pods in “eXistenZ” all demonstrate his commitment to rendering the abstract concept of bodily transformation in visceral, concrete terms.

Notably, Cronenberg has preferred practical effects over digital alternatives whenever possible, believing that physically constructed props and makeup create a tangible reality that CGI cannot match. This preference for the tactile and physical connects to his broader interest in the material reality of the human body.

Architectural Spaces

Cronenberg frequently uses architecture to reflect psychological states and power dynamics. The sterile hallways of the Keloid Clinic in “Rabid,” the Toronto high-rise in “Shivers,” and the bathhouse in “Eastern Promises” all function as extensions of the characters’ inner worlds and the social systems that contain them.

In “Dead Ringers,” the twins’ apartment and clinic are designed with modernist precision that reflects their initially controlled personalities, while the gradual disintegration of these spaces mirrors their psychological breakdown. Similarly, in “Cosmopolis,” the hermetically sealed limousine represents both the protagonist’s wealth-enabled isolation and his psychological detachment from the world around him.

Working Relationships: Cronenberg’s Collaborators

Throughout his career, Cronenberg has maintained long-term working relationships with key collaborators who have helped shape his distinctive vision.

Howard Shore: Musical Identity

Composer Howard Shore has scored all but one of Cronenberg’s films since “The Brood” in 1979, creating one of cinema’s most enduring director-composer partnerships. Shore’s music, characterized by its rich orchestration and emotional depth, provides a crucial counterpoint to Cronenberg’s often detached visual style. Rather than simply underscoring horror elements, Shore’s compositions often introduce emotional complexity and ambiguity, suggesting the psychological dimensions beneath physical transformations.

The versatility of Shore’s work for Cronenberg is remarkable, ranging from the electronic textures of “Videodrome” to the lush romanticism of “Dead Ringers” and the classical influences in “A Dangerous Method.” This musical range has supported Cronenberg’s own evolution as a filmmaker while maintaining a consistent artistic sensibility.

Peter Suschitzky: Visual Clarity

Since “Dead Ringers,” cinematographer Peter Suschitzky has been Cronenberg’s primary visual collaborator, helping to define the crisp, precise look of his mature work. Suschitzky’s lighting typically avoids expressionistic techniques in favor of clarity and definition, creating a visual style that presents even the most extraordinary content with documentary-like precision.

This approach is particularly evident in “Crash,” where potentially sensationalistic material is presented with a cool, detached gaze that refuses either to condemn or celebrate its characters’ transgressive sexuality. Similarly, in “A History of Violence,” Suschitzky’s clear, straightforward visual style grounds the film’s exploration of identity and brutality in a recognizable reality.

Carol Spier: Production Design

Production designer Carol Spier worked on thirteen Cronenberg films, creating distinctive environments that support his thematic concerns. From the institutional sterility of “The Brood” to the hallucinatory typewriters of “Naked Lunch” and the clinical interiors of “Dead Ringers,” Spier’s designs have given concrete form to Cronenberg’s abstract concepts.

Particularly notable is Spier’s work on “eXistenZ,” where she created tactile, organic game pods that plug directly into players’ spines. These objects, which resemble living organs more than traditional technology, perfectly embody Cronenberg’s vision of technology as an extension of human biology rather than something separate from it.

Ronald Sanders: Editorial Control

Editor Ronald Sanders has cut most of Cronenberg’s films since “The Brood,” helping to establish the director’s characteristic rhythm and pacing. Cronenberg’s films typically avoid rapid cutting in favor of measured sequences that allow viewers to fully register both physical transformations and psychological reactions. This editorial approach creates a tension between disturbing content and formal control that defines the Cronenbergian viewing experience.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

David Cronenberg’s influence extends far beyond his own filmography, impacting multiple generations of filmmakers and artists across various media. His contribution to cinema can be measured not just in the quality of his individual films but in his expansion of what film can depict and express.

Influence on Cinema

Numerous contemporary filmmakers acknowledge Cronenberg’s influence on their work. Directors as diverse as Guillermo del Toro, Julia Ducournau, Brandon Cronenberg (his son), and Nicolas Winding Refn have cited him as an inspiration. His impact is particularly evident in films that explore bodily transformation and the psychological implications of physical change.

Cronenberg helped legitimize horror and science fiction as vehicles for serious artistic expression, demonstrating that genre conventions could be used to explore profound philosophical and psychological questions. By bringing art-house sensibilities to traditionally disreputable genres, he paved the way for the current era of elevated genre filmmaking.

His unflinching approach to potentially controversial subject matter has expanded cinema’s capacity to address taboo topics. Films like “Crash” and “Videodrome” challenged censorship boundaries while maintaining artistic integrity, creating precedents for future filmmakers interested in exploring transgressive material.

Beyond Film: Broader Cultural Influence

Cronenberg’s impact extends beyond cinema into other art forms. His visual aesthetic and thematic preoccupations have influenced fashion designers, visual artists, and photographers drawn to his exploration of the body as both subject and medium. The term “Cronenbergian” has entered critical vocabulary as shorthand for works that combine bodily transformation with psychological depth and philosophical inquiry.

In literature, Cronenberg’s influence can be seen in the works of authors who explore similar territory, from the technological body horror of early William Gibson to the medical grotesqueries of Chuck Palahniuk. His adaptation of previously “unfilmable” works like “Naked Lunch” has also expanded notions of how literature and cinema can interact, suggesting new possibilities for cross-media inspiration.

Music videos and advertising have borrowed visual elements from Cronenberg’s films, particularly his distinctive body horror imagery. From Charli XCX’s “Famous” (which directly references “Videodrome”) to fashion campaigns that echo the clinical eroticism of “Crash,” his aesthetic influence permeates popular culture in sometimes surprising ways.

Critical Reception and Academic Interest

Cronenberg’s work has generated substantial academic and critical discourse, with scholarly books and articles analyzing his films from philosophical, psychological, feminist, and technological perspectives. His exploration of posthuman themes and embodied consciousness has made him a key reference point in discussions of how technology is changing human identity and experience.

Initially dismissed by some critics as merely exploitative, Cronenberg’s early horror films have been progressively reevaluated as sophisticated explorations of contemporary anxieties about technology, medicine, and bodily vulnerability. This critical reassessment demonstrates how his work has consistently anticipated cultural concerns that would later become mainstream preoccupations.

Awards and Recognition

While Cronenberg’s work has sometimes been too challenging for mainstream awards recognition, he has received significant honors throughout his career. These include multiple Genie Awards (Canadian film awards), the Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize for “Crash,” and lifetime achievement awards from organizations including the Venice Film Festival, the Toronto International Film Festival, and the Directors Guild of Canada.

In 2014, Cronenberg was appointed Officer of the Order of Canada, one of the country’s highest civilian honors, recognizing his contribution to Canadian culture. This official recognition reflects his status as both an uncompromising artist and a significant cultural figure who has helped define Canadian cinema on the world stage.

The Man Behind the Camera

Despite the often disturbing nature of his films, Cronenberg himself presents a striking contrast to the material he creates. Soft-spoken, intellectual, and thoughtful in interviews, he discusses even his most controversial work with analytical detachment and philosophical depth. This discrepancy between the man and his art has led some critics to characterize him as “the most horrific and the most civilized of contemporary filmmakers.”

Cronenberg’s background in literature and science has informed his approach to filmmaking throughout his career. His interest in writers like William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, and Franz Kafka reflects his attraction to literature that explores transformation, alienation, and the fragility of human identity. Similarly, his early studies in biochemistry provided a foundation for his sophisticated exploration of bodily processes and medical themes.

Unlike many directors associated with horror, Cronenberg has never disavowed his early genre work in favor of more “respectable” projects. Instead, he has maintained that his horror films were always vehicles for serious ideas, part of a consistent artistic journey rather than a phase to be outgrown. This integrity has earned him respect even from critics initially skeptical of his graphic content.

Conclusion: The Continuing Relevance of David Cronenberg

As technology increasingly blurs the boundaries between human and machine, physical and virtual, Cronenberg’s explorations of these territories appear increasingly prescient. His early films anticipated concerns about viral contagion, technological dependency, and media saturation that have become defining issues of contemporary life. Meanwhile, his later works continue to explore how identity is shaped, fragmented, and reassembled in a world of constant technological and social change.

What distinguishes Cronenberg’s work from simple shock value or exploitation is its profound engagement with the human condition. Behind the graphic imagery lies a deeply humanistic concern with how we maintain our identity and connection in the face of transformative forces beyond our control. Whether depicting literal bodily mutations or more subtle psychological transformations, his films ultimately ask what it means to be human in a world where traditional boundaries are increasingly unstable.

In an era of artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and virtual reality, Cronenberg’s vision of humanity as simultaneously vulnerable to and complicit in its own transformation feels more relevant than ever. His work reminds us that evolution—whether biological, technological, or psychological—is never painless but may be necessary for survival in a changing world. As we navigate our own relationships with technology and bodily vulnerability, Cronenberg’s unflinching gaze continues to provide both warning and wisdom about the challenges of maintaining human identity in posthuman times.

David Cronenberg stands as one of cinema’s true originals—a filmmaker who has created a unique body of work that defies easy categorization while maintaining remarkable thematic consistency. From his early experimental films to his more recent dramatic works, he has remained true to his vision while constantly evolving as an artist. In doing so, he has expanded our understanding of what film can depict and express, leaving an indelible mark on cinema and culture that continues to resonate and inspire.