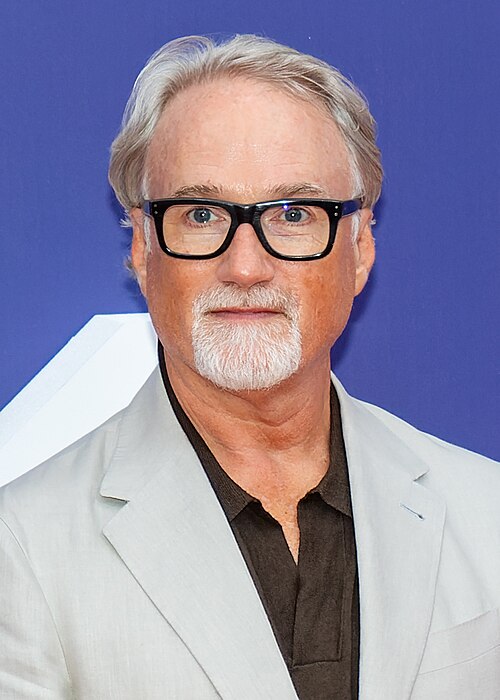

David Fincher is one of the few directors who have made name for themselves in the field of modern American cinema. Known for his meticulous approach to filmmaking, psychological depth, and visual precision, Fincher has crafted a body of work that stands as a testament to cinema’s potential for both artistic expression and commercial success. From his early days directing music videos to becoming one of Hollywood’s most respected auteurs, Fincher’s journey is a fascinating study in creative evolution, technical innovation, and unwavering artistic vision.

Early Life and Formative Years

Childhood and Adolescence

David Andrew Leo Fincher was born on August 28, 1962, in Denver, Colorado. His early exposure to the world of filmmaking came through his father, Howard Fincher, who worked as a bureau chief and writer for Life magazine. When Fincher was two years old, the family moved to San Anselmo, California, where he would spend much of his childhood. This relocation to the San Francisco Bay Area would prove significant, placing the young Fincher in proximity to the burgeoning film scene of Northern California.

Growing up in Marin County during the late 1960s and 1970s, Fincher developed an early fascination with filmmaking. By his own account, his interest in directing was sparked at age eight after watching the documentary “The Making of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1970). This behind-the-scenes glimpse into the filmmaking process ignited a passion that would define his life’s trajectory.

As a teenager, Fincher began experimenting with filmmaking, using an 8mm camera to create homemade movies. These early creative endeavors revealed not only a natural talent but also the methodical perfectionism that would become his trademark. Even in these formative projects, his attention to detail and visual composition was apparent.

Education and Early Career

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Fincher did not pursue formal film school education. Instead, he began his career at the age of 18 when he secured a job at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), George Lucas’s visual effects company. Between 1980 and 1984, Fincher worked as a production assistant and assistant cameraman at ILM, contributing to projects including “Return of the Jedi” (1983) and “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” (1984).

This practical, hands-on experience at ILM provided Fincher with invaluable technical knowledge and insight into the filmmaking process. Working within the Lucas ecosystem exposed him to cutting-edge visual effects techniques and the meticulous planning required for complex productions. This experience would form the foundation of Fincher’s approach to filmmaking—one characterized by technical precision, visual innovation, and exhaustive attention to detail.

Growing frustrated with the limitations of his role at ILM, Fincher left to pursue directing opportunities. In 1984, he co-founded Propaganda Films alongside directors like Michael Bay, Spike Jonze, and Antoine Fuqua. This production company would become instrumental in revolutionizing the aesthetic of music videos and commercials during the 1980s and early 1990s, providing a training ground for directors who would later make the transition to feature filmmaking.

The Music Video Era

Rise Through MTV Culture

Fincher’s career gained significant momentum during the golden age of music videos in the 1980s. As MTV transformed the musical landscape, it created unprecedented opportunities for visual storytellers. Fincher seized this moment, directing a series of innovative and visually striking music videos that established him as one of the medium’s most distinctive voices.

Between 1984 and 1993, Fincher directed more than 50 music videos for artists including Madonna, Aerosmith, George Michael, The Rolling Stones, and Michael Jackson. His work during this period was characterized by technical experimentation, striking visual compositions, and narrative complexity that elevated the form beyond simple promotional material.

Landmark Music Videos

Fincher’s music video résumé includes several works that are considered landmarks of the form:

Madonna’s “Express Yourself” (1989): Drawing inspiration from Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis,” Fincher created a dystopian industrial landscape where Madonna ruled as a feline-like overseer of male workers. The video’s production design, cinematography, and sexually charged imagery made it one of the most expensive and ambitious music videos of its time. Its striking visuals and feminist themes established a creative partnership between Fincher and Madonna that would continue with several other collaborations.

Madonna’s “Vogue” (1990): Filmed in elegant black and white, this iconic video captured the ballroom dance culture of 1980s New York while referencing Hollywood glamour of the 1930s and 1940s. Fincher’s crisp visual style, precise framing, and meticulous attention to choreography created a timeless visual document that transcended the typical music video.

Aerosmith’s “Janie’s Got a Gun” (1989): This narrative-driven video demonstrated Fincher’s ability to tell complex stories in short form. Dealing with themes of abuse and revenge, the video showcased the darker aesthetic and thematic concerns that would later characterize his feature films.

George Michael’s “Freedom! ’90” (1990): Rather than featuring George Michael himself, Fincher cast supermodels including Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Tatjana Patitz, Christy Turlington, and Cindy Crawford to lip-sync the song. The video’s slick production design and innovative concept made it one of the defining visual documents of the era.

The Rolling Stones’ “Love Is Strong” (1994): This video featured the band members as giants walking through New York City, interacting with normal-sized people and the cityscape. The surreal visual effects and creative concept earned Fincher a Grammy Award for Best Music Video.

Technical and Stylistic Development

Fincher’s work in music videos allowed him to develop and refine several aspects of his filmmaking approach. The format demanded efficiency, visual impact, and technical innovation—all qualities that would later define his feature films.

Working within the constraints of music video budgets and timelines, Fincher honed his ability to achieve precise visual compositions and technical feats with maximum efficiency. He experimented with lighting techniques, camera movements, visual effects, and color palettes that would become signatures of his aesthetic.

The music video format also encouraged a non-linear, visually-driven approach to storytelling that influencedi his later work. The emphasis on creating powerful visual moments and atmospheric environments over conventional narrative became a hallmark of Fincher’s cinematic style.

Perhaps most importantly, the commercial world allowed Fincher to develop his exacting working methods. His reputation for perfectionism and demanding multiple takes was established during this period, as was his commitment to pushing technical boundaries to achieve his vision.

Feature Film Debut: The Troubled Production of “Alien 3”

A Challenging First Feature

Fincher’s transition from music videos to feature filmmaking came with his directorial debut on “Alien 3” (1992), the third installment in the successful “Alien” franchise. What might have seemed like a dream opportunity for a first-time feature director quickly revealed itself to be a challenging and ultimately frustrating experience that would shape Fincher’s approach to Hollywood filmmaking.

Taking over a troubled production that had already cycled through multiple directors and screenplay drafts, Fincher found himself constrained by studio interference, script problems, and production challenges. Shooting began without a completed script, and frequent rewrites occurred throughout production. As a young director without final cut privileges, Fincher frequently clashed with studio executives over creative decisions.

Production Challenges and Studio Interference

The production of “Alien 3” was plagued by numerous difficulties. Shooting at Pinewood Studios in England, Fincher faced resistance from a crew accustomed to different working methods. The script continued to evolve throughout filming, creating inconsistencies and narrative challenges. Studio executives from 20th Century Fox maintained a heavy presence on set, frequently overriding Fincher’s decisions.

These challenges were compounded by the technical complexity of the film, which featured extensive special effects work and the challenge of creating a convincing alien creature. The pressure of following Ridley Scott’s original “Alien” (1979) and James Cameron’s highly successful “Aliens” (1986) added another layer of difficulty to the project.

Aftermath and Lessons Learned

Released in May 1992, “Alien 3” received mixed reviews and underperformed at the box office compared to its predecessor. While the film contained visual moments that hinted at Fincher’s potential, it fell short of both critical and commercial expectations. More significantly, the experience left Fincher disillusioned with studio filmmaking.

In subsequent years, Fincher largely disowned the film, referring to the experience as a “baptism by fire” and stating in interviews that “no one hated it more than me.” He has consistently declined to participate in special features or director’s cuts for home video releases of “Alien 3.”

Despite its troubled production and mixed reception, “Alien 3” contains visual elements and themes that would recur throughout Fincher’s later work: institutional environments, characters trapped by circumstances beyond their control, and a visual palette dominated by industrial spaces and muted colors. The film’s bleak tone and nihilistic ending also prefigured the darker thematic concerns of Fincher’s subsequent projects.

Most importantly, the experience of making “Alien 3” taught Fincher crucial lessons about maintaining creative control and establishing clear boundaries with studios. Moving forward, he would approach projects with greater caution, ensuring that he had sufficient creative freedom and control before committing to direct.

Breakthrough: “Seven” and the Establishment of the Fincher Aesthetic

A Creative Rebirth

After the challenging experience of “Alien 3,” Fincher retreated to the commercial world, directing advertisements for clients including Nike, Coca-Cola, and Heineken. This return to commercial work allowed him to rebuild his confidence and creative approach while maintaining high production values and technical innovation.

Fincher’s decisive return to feature filmmaking came with “Seven” (1995), a psychological thriller that would establish him as a major directorial talent and define many of the stylistic and thematic elements that would characterize his subsequent work. Working from a screenplay by Andrew Kevin Walker, Fincher crafted a dark, rain-soaked vision of urban decay and moral corruption that resonated with audiences and critics alike.

“Seven”: Production and Visual Approach

“Seven” follows detectives David Mills (Brad Pitt) and William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) as they track a serial killer who uses the seven deadly sins as his modus operandi. From the outset, Fincher fought to maintain the integrity of Walker’s dark screenplay, particularly its controversial ending. This battle for creative control reflected the lessons learned from his experience on “Alien 3.”

Visually, “Seven” established what would become recognized as the Fincher aesthetic. Working with cinematographer Darius Khondji, Fincher created a world of perpetual rain, shadow, and urban decay. The film’s distinctive look was achieved through a photochemical process called bleach bypass, which retains silver in the film stock, creating higher contrast and desaturated colors.

The film’s opening title sequence, designed by Kyle Cooper, set a new standard for main titles in cinema. The jittery, disjointed typography and disturbing imagery provided a perfect introduction to the film’s themes while establishing a visual language that would influence title design for decades to come.

Critical and Commercial Success

Released in September 1995, “Seven” became both a critical and commercial success, grossing over $327 million worldwide against a $33 million budget. Critics praised the film’s visual style, performances, and unflinching examination of evil. The film’s shocking ending, which Fincher had fought to preserve, became one of the most discussed film conclusions of the decade.

The success of “Seven” provided Fincher with the creative capital to pursue more challenging projects while establishing his reputation as a director with both artistic vision and commercial viability. It also began his long-standing collaboration with actor Brad Pitt, who would appear in several of his subsequent films.

“The Game”: Continuing Exploration of Control and Paranoia

Following the success of “Seven,” Fincher directed “The Game” (1997), a psychological thriller starring Michael Douglas as Nicholas Van Orton, a wealthy investment banker who becomes involved in a mysterious “game” that blurs the line between reality and fiction. While less commercially successful than “Seven,” “The Game” further refined Fincher’s thematic concerns and visual approach.

The film’s exploration of control, paranoia, and identity prefigured themes that would recur throughout Fincher’s filmography. Visually, “The Game” continued Fincher’s collaboration with cinematographer Harris Savides, developing the director’s distinctive visual style characterized by carefully controlled compositions, muted color palettes, and atmospheric lighting.

Although “The Game” received positive reviews, its box office performance was more modest than “Seven.” Nevertheless, the film has gained appreciation over time, particularly for its complex narrative structure and examination of privilege and redemption.

“Fight Club”: Controversy and Cult Status

A Divisive Cultural Phenomenon

Fincher’s next project, “Fight Club” (1999), would prove to be his most controversial and, ultimately, one of his most culturally significant films. Adapted from Chuck Palahniuk’s novel of the same name, “Fight Club” tells the story of an unnamed insomniac narrator (Edward Norton) who forms an underground fighting club with soap salesman Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), eventually spawning a nihilistic terrorist organization.

From its inception, “Fight Club” was a challenging project. The film’s anti-consumerist themes, graphic violence, and provocative content made studio executives nervous. Working with a budget of $63 million from 20th Century Fox, Fincher created a film that challenged conventions of narrative and visual storytelling while delivering a scathing critique of masculinity in crisis and consumer culture.

Visual Innovation and Technical Mastery

“Fight Club” represented a significant technical achievement for Fincher. Working with cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, Fincher developed a distinctive visual style that combined gritty realism with surrealistic elements. The film’s desaturated color palette, high-contrast lighting, and innovative camera techniques created a world that mirrored the narrator’s fractured psychological state.

The film featured several groundbreaking visual effects sequences, including the famous “IKEA catalog” scene, where furniture and product descriptions appear as 3D elements in the narrator’s apartment. Fincher also pioneered the use of invisible digital effects to enhance storytelling rather than create spectacle, a technique that would become increasingly important in his later work.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its release in October 1999, “Fight Club” polarized critics and underperformed at the box office, grossing $101 million worldwide against its $63 million budget. Many reviewers were put off by the film’s violence and perceived nihilism, while others recognized its satirical intent and technical achievements.

Despite its initial mixed reception, “Fight Club” quickly developed a devoted cult following and experienced a significant reevaluation in the years following its theatrical release. Strong DVD sales and word-of-mouth recommendation transformed the film from a commercial disappointment to a cultural touchstone. By the early 2000s, “Fight Club” had become one of the most discussed and referenced films of its era, influencing visual style, narrative structure, and thematic exploration across various media.

The film’s iconic status was solidified by its quotable dialogue, distinctive visual moments, and complex themes that rewarded repeated viewing. “Fight Club” is now regularly included in lists of the greatest films of the 1990s and is studied in film courses as an example of postmodern cinema. Its exploration of masculinity, consumer culture, and identity has generated extensive academic analysis and cultural commentary.

For Fincher, “Fight Club” represented both a creative triumph and a commercial lesson. While the film’s initial reception might have discouraged a less committed filmmaker, its subsequent reappraisal vindicated Fincher’s artistic choices and reinforced his commitment to challenging material.

Digital Pioneering and Technical Innovation

Early Adoption of Digital Filmmaking

Throughout his career, Fincher has been at the forefront of embracing new technologies to enhance the filmmaking process. His transition to digital filmmaking marked a significant shift not only in his own work but in Hollywood’s approach to production methods.

Fincher’s 2007 film “Zodiac” represented a turning point in the adoption of digital cinematography for major Hollywood productions. While not the first feature film shot digitally, “Zodiac” was among the first big-budget Hollywood productions to be shot primarily using a digital camera—specifically, the Thomson Viper FilmStream Camera. Working with cinematographer Harris Savides, Fincher demonstrated that digital cinematography could achieve the visual quality and artistic control previously associated only with film.

This early adoption of digital technology reflected Fincher’s interest in precision and control. Digital cinematography allowed for immediate review of footage, longer takes without the need to change film magazines, and greater flexibility in post-production. These advantages aligned perfectly with Fincher’s meticulous approach to filmmaking.

“The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”: Technical Achievement

Fincher’s embrace of digital technology reached new heights with “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” (2008). The film’s central conceit—a character who ages in reverse—presented unprecedented technical challenges that were solved through innovative digital effects.

Working with visual effects supervisor Eric Barba and digital effects house Digital Domain, Fincher pioneered a technique called “performance capture” that allowed Brad Pitt’s facial expressions to be digitally mapped onto the faces of different actors playing Benjamin Button at various ages. This groundbreaking approach, combined with traditional makeup effects, created a seamless portrayal of a character aging backward throughout a lifetime.

“Benjamin Button” received 13 Academy Award nominations and won three, including Best Visual Effects. More importantly, it demonstrated how digital technology could be used in service of storytelling and character development rather than mere spectacle. The film’s technical innovations influenced subsequent films dealing with aging characters and digital performance capture.

Digital Workflow and Post-Production Innovation

Beyond visible special effects, Fincher revolutionized the entire filmmaking workflow through his embrace of digital technologies. He was an early adopter of digital intermediate processes, which allow for precise color grading and visual manipulation of the entire film. This approach gave Fincher unprecedented control over the final look of his films, enabling him to create the distinctive visual palettes that characterize his work.

Fincher also embraced the possibilities of non-linear digital editing, working closely with editors like Angus Wall and Kirk Baxter to develop a highly detailed approach to cutting and constructing scenes. This collaboration yielded back-to-back Academy Awards for Wall and Baxter for their editing of “The Social Network” (2010) and “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” (2011).

The RED Digital Cinema Partnership

Fincher’s commitment to digital innovation led to a strong relationship with RED Digital Cinema, a company specializing in digital cinematography cameras. Beginning with “The Social Network,” Fincher has shot most of his subsequent films on RED cameras, helping to establish these systems as viable alternatives to traditional film for high-end productions.

This partnership has allowed Fincher to push technical boundaries while maintaining his exacting standards for image quality. For “Gone Girl” (2014), Fincher and cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth used the RED Epic Dragon, achieving a look that combined clinical precision with emotional resonance, perfectly matching the film’s themes of appearance versus reality.

Directorial Style and Working Methods

The Perfectionist Approach: Multiple Takes and Precision

Perhaps the most widely discussed aspect of Fincher’s directorial methodology is his penchant for shooting numerous takes of each scene. This approach, which has become legendary in the film industry, reflects his commitment to achieving a precise, controlled performance from every element in front of the camera.

Actors who have worked with Fincher frequently comment on his demand for multiple takes, with scenes sometimes requiring 50 or more repetitions. Jake Gyllenhaal, who starred in “Zodiac,” has described shooting 70 takes of a single scene, while Jesse Eisenberg reportedly performed the opening scene of “The Social Network” 99 times. This process is not about waiting for a magical moment of spontaneity, but rather about achieving a level of precision where the performance becomes second nature to the actor, stripping away self-consciousness and calculation.

Fincher has explained this approach as a means of exhausting the obvious choices, forcing actors beyond their initial instincts into territory where authenticity emerges from mastery. As he told Film Comment: “I hate earnestness in performance… I hate when I see actors who think they’re being funny or who think they’re being dramatic.”

This perfectionism extends beyond performances to every technical aspect of production. Fincher is known for his precise camera movements, carefully designed compositions, and meticulous attention to production design details. Each element in a Fincher film is deliberately chosen and precisely executed, creating a controlled environment where nothing is left to chance.

Collaborative Relationships

Despite his reputation for exactitude, Fincher has maintained long-term collaborative relationships with many actors and crew members. Brad Pitt has appeared in three of his films (“Seven,” “Fight Club,” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”), while Rooney Mara, Jesse Eisenberg, and Ben Affleck have all delivered career-defining performances under his direction.

Behind the camera, Fincher has established particularly significant creative partnerships with:

Jeff Cronenweth (cinematographer): Son of legendary “Blade Runner” cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, Jeff has shot several of Fincher’s films including “Fight Club,” “The Social Network,” and “Gone Girl.” Their collaboration has defined the precise, controlled visual style associated with Fincher’s work.

Angus Wall and Kirk Baxter (editors): This editing team has worked on most of Fincher’s films since “Zodiac,” winning Academy Awards for “The Social Network” and “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.” Their meticulous approach to cutting complements Fincher’s directorial precision.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (composers): Beginning with “The Social Network,” for which they won an Academy Award, this musical duo has composed innovative electronic scores for several Fincher films, creating soundscapes that enhance the psychological dimension of his storytelling.

Donald Graham Burt (production designer): Burt has designed the physical environments for most of Fincher’s films since “Zodiac,” creating detailed, authentic spaces that support the narrative while reflecting characters’ psychological states.

These long-term collaborations have allowed Fincher to develop a consistent aesthetic while continuing to innovate within his established style. The creative shorthand developed through repeated collaborations enables a level of efficiency and mutual understanding that serves his perfectionist approach.

Pre-Production and Planning

Fincher’s meticulous approach extends to pre-production, where extensive planning lays the groundwork for his precise execution. He is known for thorough storyboarding and previsualization, often creating detailed animatics (animated storyboards) that map out complex sequences before shooting begins.

This planning serves multiple purposes: it allows technical challenges to be addressed in advance, provides clear communication to cast and crew about what will be required, and establishes a blueprint for the visual storytelling. However, Fincher’s planning is not rigid—it creates a framework within which creative decisions can be made efficiently on set.

Fincher’s background in visual effects and commercial production informs this approach. Having worked at Industrial Light & Magic and directed numerous commercials and music videos, he developed a thorough understanding of technical processes and efficient production methods. This experience allows him to envision the entire filmmaking process from inception to completion, anticipating challenges and planning accordingly.

Visual Style and Technical Approach

Fincher’s visual style is characterized by controlled camera movement, precise composition, and distinctive color palettes. Typically working with a deliberately limited color scheme—often favoring cool tones, desaturated colors, and high contrast—he creates visually cohesive worlds that reflect the psychological states of his characters.

His camera work tends toward smoothness and precision, with carefully motivated movements that enhance storytelling rather than drawing attention to themselves. Even in complex tracking shots or dynamic sequences, there is a sense of control and purpose to every movement. This precision extends to framing and composition, with Fincher frequently employing symmetrical compositions and architectural framing devices.

Lighting in Fincher’s films often creates a sense of environmental realism while maintaining a stylized quality. He frequently employs practical light sources within the frame, creating natural-seeming motivation for the illumination while maintaining careful control over the visual mood. Shadows play a crucial role in his visual storytelling, sometimes concealing information or creating visual metaphors for the themes of secrecy and hidden truth that recur throughout his work.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

“Zodiac”: Obsession and the Pursuit of Truth

“Zodiac” (2007) marked a significant evolution in Fincher’s filmmaking approach. Based on the real-life investigation of the Zodiac Killer who terrorized the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the film represented Fincher’s first direct engagement with historical events and demonstrated a new patience in his storytelling approach.

Starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Mark Ruffalo, and Robert Downey Jr., “Zodiac” examines the investigation of the Zodiac killings through the experiences of cartoonist Robert Graysmith, detective Dave Toschi, and journalist Paul Avery. Rather than focusing primarily on the killings themselves, Fincher crafted a meticulous procedural that documented the painstaking, often frustrating process of investigation.

The film exemplifies several of Fincher’s recurring themes, particularly obsession and the elusive nature of truth. As the investigation extends over years without resolution, the characters become consumed by the case, sacrificing personal relationships and psychological wellbeing in pursuit of answers that remain perpetually out of reach. This focus on obsession connects “Zodiac” to earlier Fincher works like “Seven” and later ones like “The Social Network.”

“Zodiac” also represented a stylistic evolution for Fincher. While retaining his characteristic visual precision, the film adopted a more restrained approach appropriate to its period setting and documentary-like attention to detail. Working with cinematographer Harris Savides, Fincher created a visual style that evoked both the period setting and the psychological states of the characters without drawing undue attention to itself.

Critical reception for “Zodiac” was overwhelmingly positive, with many critics considering it among Fincher’s finest works. Though not a major commercial success upon release, the film has grown in stature over time and is now frequently cited in discussions of the best films of the 2000s. Its influence can be seen in subsequent procedural dramas, particularly those dealing with unsolved cases and obsessive investigations.

“The Social Network”: Ambition, Isolation, and the Digital Age

“The Social Network” (2010) represented both a departure and a culmination for Fincher. Chronicling the founding of Facebook through the experiences of Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg), the film combined Fincher’s visual precision and psychological insight with Aaron Sorkin’s rapid-fire dialogue, creating a compelling examination of ambition, betrayal, and the digital revolution.

Working from Sorkin’s script, Fincher transformed what might have seemed like dry subject matter—the founding of a website and subsequent legal battles—into a propulsive drama about human connection and disconnection in the digital age. The film’s central irony—that a platform designed to facilitate social connection was created by someone struggling with interpersonal relationships—provided a rich thematic foundation.

Visually, “The Social Network” continued Fincher’s evolution toward a more restrained style. Working with cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, he created a visual approach that balanced documentary-like realism with stylized elements that enhanced the story’s themes. The film’s distinctive color palette, dominated by amber and teal tones, created a visual cohesion that united various timelines and locations.

The film’s opening sequence, a rapid-fire verbal duel between Zuckerberg and his girlfriend Erica Albright (Rooney Mara), established both the film’s dialogue-driven approach and its central thematic concern: the tension between intellectual brilliance and emotional intelligence. This sequence, which required numerous takes to achieve the precise timing and delivery Fincher sought, exemplifies his meticulous approach to performance.

“The Social Network” received widespread critical acclaim upon its release, earning eight Academy Award nominations and winning three (Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Film Editing, and Best Original Score). The film’s examination of ambition, power, and the social impact of technology resonated strongly with audiences and critics, establishing it as one of the defining films about the early 21st century digital revolution.

“Gone Girl”: Gender, Media, and Manipulation

“Gone Girl” (2014), adapted from Gillian Flynn’s bestselling novel, represented another evolution in Fincher’s exploration of dark psychological territory. The film follows Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) as he becomes the prime suspect in his wife Amy’s (Rosamund Pike) disappearance, revealing a marriage built on mutual deception and manipulation.

Working from Flynn’s own screenplay adaptation, Fincher crafted a film that functions simultaneously as a thriller, a dark satire of media culture, and an examination of gender dynamics and performative identity. The film’s structure, which shifts perspective midway to reveal Amy’s elaborate plot, allows for a complex exploration of unreliable narration and subjective truth.

“Gone Girl” continues Fincher’s interest in the construction and manipulation of narrative. Just as the characters in “Fight Club” create fictionalizations of themselves, Nick and Amy Dunne construct versions of themselves and their relationship for different audiences—each other, their families, the media, and ultimately the viewer. This theme connects to Fincher’s broader interest in how stories shape perception and reality.

Visually, “Gone Girl” represents a refinement of Fincher’s established aesthetic. Working again with cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, he created a look that combines suburban banality with underlying menace. The film’s color palette shifts subtly throughout, reflecting the changing emotional temperature and perspective of the narrative.

Upon release, “Gone Girl” received critical acclaim, particularly for Rosamund Pike’s performance as Amy Dunne, which earned her an Academy Award nomination. The film was also a substantial commercial success, grossing over $369 million worldwide. Its examination of media manipulation, gender performance, and the dark undercurrents of seemingly perfect relationships resonated with audiences and generated substantial cultural discussion.

Television and Streaming Success

“House of Cards”: Establishing a New Television Model

While primarily known as a film director, Fincher has made significant contributions to the television landscape, particularly through his work with streaming platforms. His most influential television project, “House of Cards,” helped establish Netflix as a major player in original content production and influenced the quality and approach of streaming television.

Fincher served as executive producer for “House of Cards” and directed the first two episodes, establishing the visual style and tone that would characterize the series. The show, which starred Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright as a manipulative political power couple, became Netflix’s first major original programming success when it debuted in 2013.

By bringing his cinematic sensibility to television, Fincher helped elevate expectations for visual quality and storytelling complexity in the medium. The show’s success demonstrated the viability of the streaming model for high-quality original programming, influencing the subsequent explosion of streaming content production.

“Mindhunter”: Serial Killers and the Birth of Criminal Profiling

Fincher’s most personal television project, “Mindhunter,” debuted on Netflix in 2017. Based on the book “Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit” by John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker, the series explores the early days of criminal profiling through the experiences of FBI agents Holden Ford (Jonathan Groff) and Bill Tench (Holt McCallany) as they interview imprisoned serial killers to understand their psychology.

“Mindhunter” represents a culmination of Fincher’s long-standing interest in serial killers and criminal psychology, themes he explored previously in “Seven” and “Zodiac.” The series allowed him to examine these subjects with the expanded canvas and character development possibilities afforded by serial television.

Fincher directed seven episodes across the show’s two seasons, establishing a distinctive visual approach characterized by formal composition, muted color palettes, and precise camera movements. The series’ interview scenes, in which the agents confront notorious killers including Edmund Kemper, Richard Speck, and Charles Manson, showcase Fincher’s ability to create tension through dialogue and performance rather than explicit violence.

Despite critical acclaim and a devoted audience, “Mindhunter” was placed on indefinite hold after its second season, with Fincher turning his attention to other projects. Nevertheless, the series represents an important addition to his body of work, demonstrating his ability to adapt his filmmaking approach to the television format while maintaining his distinctive thematic concerns and visual style.

“Love, Death & Robots”: Animation and Anthology Storytelling

Fincher ventured into new territory with “Love, Death & Robots,” an animated anthology series he executive produced alongside Tim Miller for Netflix. Debuting in 2019, the series features short animated stories spanning various genres including science fiction, horror, and fantasy, each created by different animation teams from around the world.

This project allowed Fincher to explore storytelling possibilities beyond the constraints of live-action filmmaking, embracing diverse animation styles and narratives. While he did not direct any episodes himself, his influence can be seen in the series’ technical ambition, adult themes, and visual innovation.

Recent Work and Continued Evolution

“Mank”: Personal Filmmaking and Hollywood History

“Mank” (2020) represented a significant departure for Fincher—a black and white period drama about screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) and the writing of “Citizen Kane.” Based on a screenplay by Fincher’s father, Jack Fincher, the project was deeply personal for the director, who had been attempting to bring it to screen for decades.

While stylistically different from his previous work, “Mank” nonetheless displays Fincher’s characteristic attention to detail and visual precision. Working with cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, Fincher created a visual style that evokes 1930s and 1940s Hollywood cinema while incorporating modern techniques that enhance storytelling.

The film received 10 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director for Fincher. While it won only for Best Cinematography and Best Production Design, “Mank” demonstrated Fincher’s continued ability to evolve as a filmmaker while maintaining his core strengths of visual sophistication and psychological depth.

“The Killer”: A Return to Thriller Territory

Fincher’s most recent feature film, “The Killer” (2023), starring Michael Fassbender as a methodical assassin, returned the director to the psychological thriller territory where he has frequently done his most acclaimed work. Adapted from a French graphic novel series, the film continues Fincher’s exploration of meticulous professionals operating according to rigid personal codes.

The film’s protagonist, a nameless assassin, embodies many of the qualities associated with Fincher himself: perfectionism, methodical planning, and emotional detachment. This self-reflexive quality gives “The Killer” a personal dimension beneath its genre trappings, allowing Fincher to examine his own creative approach through the lens of a fictional character.

Working again with cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, Fincher crafted a visually controlled experience that reflects the protagonist’s disciplined mindset while also capturing the chaos that ensues when his carefully laid plans unravel. The film’s restrained visual style, precise compositions, and meticulous attention to procedural detail reinforce its thematic exploration of control and its limitations.

Released on Netflix after a limited theatrical run, “The Killer” received generally positive reviews, with particular praise for Fassbender’s performance and Fincher’s technical precision. While perhaps not achieving the cultural impact of “Fight Club” or “The Social Network,” the film demonstrated Fincher’s continued mastery of the thriller genre and his ability to find new dimensions within established formats.

Directorial Trademarks and Visual Signatures

Color and Lighting

A distinctive aspect of Fincher’s visual approach is his sophisticated use of color and lighting to establish mood and reinforce thematic elements. Throughout his filmography, Fincher has favored controlled color palettes that create visual cohesion while subtly influencing the viewer’s emotional response.

In his early features, particularly “Seven” and “Fight Club,” Fincher employed desaturated color schemes dominated by greens, ambers, and blues, creating environments that feel simultaneously realistic and stylized. This approach continued in “Zodiac,” where the color palette shifts subtly throughout the film, reflecting both the changing decades of the narrative and the evolving psychological states of the characters.

“The Social Network” established what would become recognized as a signature Fincher color treatment—a controlled palette dominated by amber and teal tones that creates visual consistency while allowing for emotional variation. This approach was refined in subsequent films like “Gone Girl,” where color choices subtly reinforce character perspectives and narrative developments.

Fincher’s lighting approach typically balances naturalism with stylization, creating environments that feel authentic while maintaining precise control over mood and atmosphere. He frequently employs practical light sources within the frame, using visible lamps, overhead fixtures, and natural light to create plausible motivation for illumination while carefully controlling its quality and effect.

Shadows play a crucial role in Fincher’s visual storytelling, often serving as visual metaphors for hidden truths, moral ambiguity, or psychological darkness. This is particularly evident in films like “Seven,” where shadows literally and figuratively obscure information, and “The Social Network,” where selective illumination emphasizes characters’ isolation even in crowded settings.

Camera Movement and Framing

Fincher’s approach to camera movement emphasizes precision and purpose. Rather than employing showy or unmotivated movement, his camera typically moves with deliberate intent, enhancing storytelling through carefully chosen perspectives and revelations.

One of Fincher’s most distinctive camera techniques is the precisely controlled tracking shot that follows characters through environments, establishing spatial relationships while maintaining focus on key elements. This technique is particularly evident in films like “Panic Room,” where the camera seemingly passes through physical objects to reveal the house’s layout, and in “The Social Network,” where fluid movements connect characters across crowded spaces.

Fincher frequently employs symmetrical compositions and architectural framing devices, creating images of precise balance that reflect his overall aesthetic control. This approach is evident in “The Game,” where the protagonist’s orderly life is visually established through symmetrical compositions that are gradually disrupted as his control unravels, and in “Gone Girl,” where the perfect symmetry of the Dunne home establishes a visual metaphor for their seemingly perfect marriage.

Another Fincher trademark is the God’s-eye view—shots from directly overhead that present environments and actions with clinical detachment. This technique appears throughout his filmography, from the crime scenes in “Seven” to the rowing sequence in “The Social Network,” creating moments of visual omniscience that complement the films’ thematic concerns with observation and judgment.

Title Sequences and Visual Design

Fincher’s background in commercial and music video production is evident in his sophisticated approach to title sequences, which frequently function as self-contained artistic statements that establish tone and introduce thematic elements. Working with design companies like Imaginary Forces and Blur Studio, Fincher has created some of contemporary cinema’s most memorable opening sequences.

The title sequence for “Seven,” designed by Kyle Cooper, established a new standard for main titles with its jittery typography, disturbing imagery, and Nine Inch Nails soundtrack. This sequence functions as both a character study of the film’s killer and a thematic preview of the narrative to follow.

For “Fight Club,” Fincher created an opening sequence that begins inside the protagonist’s brain and pulls back through his body to reveal a gun in his mouth, establishing both the film’s visual inventiveness and its concern with internal psychological states. Similar innovation is evident in the title sequence of “Panic Room,” which places three-dimensional text within the physical environment of the film’s setting.

“The Social Network” features an opening title sequence that contrasts with Fincher’s previous work, employing simple white typography against black backgrounds. This minimalist approach complements the film’s focus on the digital world, where clean interfaces mask complex human dynamics.

Beyond title sequences, Fincher’s attention to visual design extends to every aspect of his films’ presentation, from promotional materials to end credits. This holistic approach to visual identity reflects his background in advertising and music videos, where creating a distinctive and cohesive visual brand is essential.

Recurring Themes and Narrative Concerns

Control and Its Limitations

A central theme throughout Fincher’s filmography is the human desire for control and the inevitable limitations of that desire. His protagonists frequently attempt to impose order on chaotic circumstances, only to discover that complete control is ultimately unattainable.

This theme is explicitly addressed in “Fight Club,” where the narrator’s attempt to create a perfectly ordered consumer lifestyle gives way to Tyler Durden’s chaotic philosophy. Similarly, “The Game” follows a protagonist whose carefully controlled existence is deliberately disrupted by forces beyond his understanding, forcing him to surrender control to achieve redemption.

In “Zodiac,” the inability to definitively identify the killer despite years of meticulous investigation demonstrates the limitations of human efforts to impose order on chaotic events. This theme continues in “The Social Network,” where Mark Zuckerberg creates a platform that organizes social relationships but cannot control his own personal connections.

“Gone Girl” presents perhaps Fincher’s most extreme exploration of control, featuring two protagonists engaged in an escalating battle to control their shared narrative. Amy Dunne’s elaborate plot represents the ultimate attempt to script reality, while the media’s influence demonstrates how narratives can be shaped and manipulated by external forces.

This thematic concern with control mirrors Fincher’s own filmmaking approach, creating an interesting tension between his meticulous directorial control and his narratives’ recognition of control’s limitations. This self-reflexive quality adds depth to his exploration of the theme, suggesting an awareness of the paradox inherent in his own creative process.

Obsession and Its Consequences

Closely related to the theme of control is Fincher’s recurring interest in obsession—the consuming focus on a goal, person, or idea that drives many of his protagonists. This obsession frequently leads to both achievement and personal destruction, creating complex character arcs that resist simple moral judgments.

In “Seven,” Detective Mills’ obsession with catching the killer ultimately plays into John Doe’s plan, while Somerset’s professional detachment allows him to maintain perspective but potentially at the cost of emotional engagement. “Zodiac” presents multiple characters consumed by the investigation, with Robert Graysmith’s obsession driving him to continue long after others have abandoned the search, simultaneously enabling his eventual insights and destroying his personal life.

“The Social Network” portrays Mark Zuckerberg’s obsessive focus on building Facebook as both the source of his extraordinary success and the cause of his personal isolation. The film suggests that the same qualities that drive exceptional achievement—single-minded focus, relentless pursuit of perfection, willingness to sacrifice other priorities—can simultaneously undermine personal relationships and emotional wellbeing.

In “Gone Girl,” obsession manifests as Amy Dunne’s meticulous planning of her own disappearance and framing of her husband—an elaborate plot requiring extraordinary commitment and attention to detail. This obsessive energy is portrayed as both impressive in its execution and disturbing in its implications, creating a morally complex portrait of vengeful determination.

Fincher’s treatment of obsession resists simple moralization, neither fully condemning nor celebrating his characters’ single-minded focus. Instead, he presents obsession as a complex human trait with both creative and destructive potential—a force that can drive exceptional achievement while exacting significant personal costs.

Institutional Failure and Individual Response

Many of Fincher’s films examine the failure of institutions to provide justice, security, or meaning, forcing individuals to seek their own solutions outside established systems. This theme reflects a distinctive American tradition of skepticism toward authority while exploring the consequences of institutional breakdown on individual psychology.

“Seven” portrays a criminal justice system unable to prevent John Doe’s methodical killings or provide meaningful justice for his victims. “Fight Club” presents contemporary consumer capitalism as a system that has failed to provide authentic meaning or purpose for a generation of men, leading to the formation of alternative, increasingly destructive communities.

“Zodiac” offers perhaps Fincher’s most detailed examination of institutional failure, portraying police departments hampered by jurisdictional boundaries, communication failures, and resource limitations in their pursuit of the Zodiac Killer. The film’s protagonists—particularly Robert Graysmith—must continue the investigation as individuals when institutional efforts falter.

“The Social Network” examines both institutional exclusivity (represented by Harvard’s final clubs) and institutional constraints (represented by the legal system that eventually adjudicates Facebook’s ownership). Zuckerberg’s creation of Facebook represents both a response to the former and an attempt to circumvent the latter.

This theme connects to Fincher’s broader interest in outsiders and individuals operating according to personal codes rather than social conventions. His protagonists frequently develop their own methodologies and moral frameworks when existing systems prove inadequate, creating tension between individual agency and social responsibility.

Technology and Human Connection

As digital technology has increasingly shaped contemporary experience, Fincher has explored its impact on human connection and identity. This theme is most explicit in “The Social Network,” which examines the creation of a platform designed to facilitate social connection by an individual struggling with his own interpersonal relationships.

The film suggests a complex relationship between digital connection and authentic human relationship, neither fully embracing techno-utopianism nor simplistic digital skepticism. Instead, it presents social media as a tool whose impact depends on the intentions and needs of its users, while acknowledging its potential to both enhance and diminish authentic connection.

This theme extends beyond “The Social Network” throughout Fincher’s work. “Zodiac” examines the limitations of pre-digital information management, portraying characters struggling to connect disparate pieces of evidence without the database technologies that would later transform investigative work. “Gone Girl” explores how media technology enables the construction and dissemination of narratives that shape public perception, demonstrating both the power and manipulation possible through digital platforms.

Fincher’s exploration of technology is informed by his own embrace of digital filmmaking tools, creating a nuanced perspective that acknowledges both the creative possibilities and potential pitfalls of technological innovation. This balanced approach allows his films to engage with technological themes without falling into either uncritical enthusiasm or reactionary fear.

Legacy and Influence

Impact on Visual Style in Contemporary Cinema

Fincher’s visual aesthetic has had a profound influence on contemporary filmmaking, establishing a style that has been widely imitated across both film and television. Elements of what might be called the “Fincher look”—controlled camera movement, desaturated color palettes, precise composition, and atmospheric lighting—have become prevalent in contemporary thrillers, dramas, and even comedies.

This influence is particularly evident in television, where shows like “True Detective,” “Mr. Robot,” and “Mindhunter” (which Fincher himself helped establish) have adopted elements of his visual approach. The rise of “quality television” in the streaming era owes much to Fincher’s demonstration that cinematic visual sophistication could be successfully translated to serialized storytelling.

Beyond specific visual techniques, Fincher’s meticulous approach to filmmaking has influenced a generation of directors who prioritize precision and control. Filmmakers including Nicolas Winding Refn, Denis Villeneuve, and Christopher Nolan have acknowledged Fincher’s influence on their work, particularly his commitment to technical excellence and visual storytelling.

Contributions to Digital Filmmaking

Fincher’s early adoption and consistent advancement of digital filmmaking technologies have significantly influenced production practices throughout the industry. His successful use of digital cameras for major studio productions helped establish their viability, contributing to the widespread transition from film to digital cinematography that has transformed the industry.

Beyond the basic shift to digital capture, Fincher pioneered workflows that maximize the creative possibilities of digital technology. His use of digital intermediate processes for precise color control, embrace of digital set extensions and invisible effects, and integration of computer-generated elements into photorealistic environments have all contributed to the evolution of contemporary production methods.

Fincher’s collaborative relationship with companies like RED Digital Cinema has also influenced equipment development, with his technical requirements and feedback helping to shape camera systems used throughout the industry. This practical influence on filmmaking tools complements his aesthetic influence, creating a comprehensive impact on how films are made.

Cultural Impact and Critical Reassessment

Several of Fincher’s films have transcended their initial reception to become significant cultural touchstones. “Fight Club,” in particular, has achieved a level of cultural penetration rare for a film that was initially considered controversial and commercially disappointing. Its dialogue, imagery, and themes have been referenced, parodied, and analyzed across various media, establishing it as one of the defining films of its era.

Similarly, “The Social Network” has become the definitive cinematic document of Facebook’s creation and the early social media era, influencing public perception of both Mark Zuckerberg and the broader tech industry. Its portrayal of ambitious young entrepreneurs reshaping society through code has become a reference point for discussions of technology’s social impact.

Critical assessment of Fincher’s work has evolved significantly over time, with early criticism of his “style over substance” giving way to recognition of the sophisticated thematic depth beneath his technical precision. Academic analysis of his films has increased substantially, examining their exploration of masculinity, technology, control, and American institutional failure.

This critical reassessment places Fincher in the lineage of technically innovative American directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and Martin Scorsese—filmmakers whose visual sophistication initially overshadowed recognition of their thematic depth. Like these directors, Fincher has increasingly been recognized as an artist whose technical precision serves complex explorations of human psychology and social dynamics.

Influence on Actors’ Careers

Fincher has consistently drawn remarkable performances from his actors, often helping to redefine their screen personas or reveal previously untapped aspects of their talent. This ability to elicit career-defining performances has established him as an actor’s director despite his reputation for demanding multiple takes and technical precision.

Brad Pitt’s performances in “Seven,” “Fight Club,” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” demonstrated range beyond his initial heartthrob image, establishing him as a versatile actor capable of complex character work. Similarly, Ben Affleck’s performance in “Gone Girl” helped redefine his screen persona at a crucial point in his career, demonstrating emotional depths that had been frequently underutilized.

Fincher has also launched or significantly elevated acting careers, including Rooney Mara (whose performance as Lisbeth Salander in “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” earned an Academy Award nomination), Jesse Eisenberg (whose portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg in “The Social Network” similarly received an Oscar nomination), and Rosamund Pike (whose Amy Dunne in “Gone Girl” became an iconic screen villain).

This consistent ability to elicit exceptional performances across a diverse range of actors speaks to Fincher’s skill in casting, character development, and performance direction. Despite his reputation for technical perfectionism, his work reveals a deep understanding of human psychology and behavior that enables him to guide actors toward authentic, nuanced performances.

Conclusion: A Definitive Voice in Contemporary Cinema

David Fincher’s evolution from music video director to one of contemporary cinema’s most distinctive and influential voices represents a remarkable creative journey. Through meticulous craftsmanship, technical innovation, and thematic consistency, he has created a body of work that examines the darker aspects of human psychology and American society with uncommon intelligence and visual sophistication.

What distinguishes Fincher from many of his contemporaries is the seamless integration of technical precision and thematic depth. While his visual style is immediately recognizable, it never exists merely for its own sake but rather serves the psychological and narrative dimensions of his storytelling. This integration creates a cinema of precision that examines messy human realities—obsession, violence, deception, and the desire for control—with clinical detachment that paradoxically enhances rather than diminishes their emotional impact.

As Fincher continues to evolve as a filmmaker, exploring new genres, technologies, and platforms, his influence on visual storytelling remains profound. From his early music videos to his recent feature films and television projects, he has consistently demonstrated that technical innovation and artistic expression are not opposing forces but complementary aspects of cinematic excellence.

In a filmmaking landscape increasingly dominated by franchise properties and formulas, Fincher represents a commitment to distinctive personal vision within mainstream American cinema. His success in bringing challenging, complex material to significant audiences demonstrates that commercial viability and artistic ambition need not be mutually exclusive. As he continues to create, Fincher’s legacy as one of his generation’s most significant filmmakers seems assured, based not only on his past achievements but on his continued ability to evolve while maintaining the core strengths that have defined his remarkable career.