There is a certain moment every seasoned cinephile recognizes — that quiet, unsettling instant when you realize you have missed something essential. Not something obscure in the sense of trivial, but something foundational that somehow remained hidden behind louder names, bigger reputations, and more frequently cited masterpieces. Discovering Konstantin Lopushanskiy feels exactly like that moment.

For anyone already familiar with Russian cinema — with Tarkovsky’s metaphysical gravity, Sokurov’s mournful textures, Klimov’s historical fury, or German’s suffocating realism — Lopushanskiy does not arrive as a stranger. And yet, he feels astonishingly new. His cinema seems to exist slightly outside the usual maps of Russian film history: neither fully embraced by mainstream science fiction discourse, nor comfortably placed within art-house traditions, nor easily marketed as political allegory. Instead, his films sit quietly, patiently, like sealed letters written after the end of the world — waiting for viewers ready to open them.

Lopushanskiy’s cinema does not ask to be admired. It asks to be endured, contemplated, and absorbed. His apocalyptic visions are not spectacles of destruction but slow, spiritual autopsies of humanity after meaning has collapsed. And once you enter his world — especially through Pisma myortvogo cheloveka (Dead Man’s Letters) and Posetitel muzeya (A Visitor to a Museum) — it becomes difficult to think about post-apocalyptic cinema, or even Russian cinema itself, in quite the same way again.

From Music to Ruins: The Making of a Singular Sensibility

Lopushanskiy’s background already hints at why his cinema feels so attuned to rhythm, silence, and emotional undertow. Trained as a musician before turning to cinema, he approaches film less like a storyteller and more like a composer of existential states. His scenes are not built around narrative propulsion but around tempo: the length of a gaze, the weight of a pause, the echo of a voice in an empty space.

His formative experience working on Tarkovsky’s Stalker is often mentioned — and inevitably so — but Lopushanskiy should not be dismissed as merely a Tarkovsky disciple. Yes, the influence is visible: the slow cinema, the metaphysical questioning, the belief that film should confront ultimate truths rather than provide answers. But Lopushanskiy diverges sharply in his emotional temperature. Where Tarkovsky searches for transcendence, Lopushanskiy remains stubbornly earthbound, staring into the wreckage of human failure without offering metaphysical escape routes.

If Tarkovsky’s cinema often reaches upward, Lopushanskiy’s digs downward — into guilt, complicity, and moral exhaustion. His worlds are not waiting to be redeemed; they are already too late. And that difference matters.

A Cinema of Aftermath, Not Catastrophe

One of the most striking aspects of Lopushanskiy’s style is his refusal to depict catastrophe itself. The bomb has already fallen. The flood has already passed. Civilization has already collapsed. What interests him is what comes after, when spectacle is over and only consequences remain.

This places him in a unique position within post-apocalyptic cinema. There are no action beats, no survivalist fantasies, no heroic arcs. His films unfold in enclosed spaces, degraded landscapes, and liminal zones — basements, ruins, coastlines, submerged cities. Humanity is not fighting for dominance or rebuilding society; it is simply existing, uncertain whether existence itself still carries meaning.

Visually, his films are drained of vitality. Colors are muted, often leaning toward grays, browns, and sickly yellows. Faces look worn, aged beyond their years. Bodies move slowly, heavily, as if gravity itself has increased after the end of the world. The environment is never neutral; it presses down on the characters, shaping their psychology as much as their physical reality.

This is cinema of entropy — not explosive, but suffocating.

Dead Man’s Letters: Writing to the Void

Pisma myortvogo cheloveka is not merely Lopushanskiy’s debut feature; it is one of the most devastating first films in the history of post-apocalyptic cinema. Watching it today, it feels less like a product of its Cold War moment and more like a timeless lament — a film permanently suspended between prophecy and aftermath.

The premise is deceptively simple: after a nuclear catastrophe, a group of survivors shelter in the basement of a destroyed museum. Among them is an aging scientist who writes letters to his son — letters that may never be read, addressed to someone who may no longer exist. These letters form the film’s emotional backbone, transforming the narrative into a confession addressed not just to a child, but to the future itself.

What makes Dead Man’s Letters extraordinary is its refusal to dramatize survival. There is no illusion that humanity will bounce back, no narrative promise of renewal. Instead, Lopushanskiy presents survival as a burden — something heavy, exhausting, and morally ambiguous. To live on is not portrayed as victory, but as responsibility: responsibility to remember, to bear witness, to carry guilt forward.

The museum setting is crucial. Surrounded by artifacts of human culture, knowledge, and achievement, the characters exist among reminders of what civilization once valued — art, history, beauty — now rendered useless by annihilation. The irony is merciless: humanity preserved its past meticulously, yet failed to preserve its future.

The letters themselves are not sentimental. They are filled with doubt, regret, and ethical reckoning. The scientist does not justify himself; he questions his role in the very systems that led to destruction. In this sense, Dead Man’s Letters becomes a moral indictment — not of abstract evil, but of intellectual complacency, technological arrogance, and ethical abdication.

Few films capture the psychological aftermath of apocalypse with such quiet ferocity. The horror here is not radiation or starvation, but the realization that humanity understood the risks — and proceeded anyway.

A Visitor to a Museum: The Ruins of Faith

If Dead Man’s Letters is about survival after destruction, A Visitor to a Museum is about meaning after collapse. It is a colder, stranger, and perhaps even more unsettling film — one that abandons conventional emotional anchors in favor of allegory, symbolism, and spiritual unease.

Set in a future ravaged by ecological catastrophe, the film follows a man obsessed with reaching a submerged city — a former center of civilization that becomes visible only when the sea recedes. This city, referred to as a “museum,” is not merely a physical location but a symbol of lost human achievement, memory, and purpose.

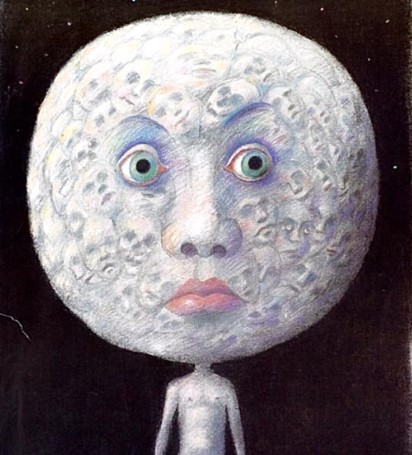

What makes the film deeply uncomfortable — and deeply fascinating — is its portrayal of post-apocalyptic society. Humanity has fractured into groups not defined by morality or intelligence, but by attitude toward meaning. The so-called “normal” people indulge in distraction, pleasure, and denial. They have adapted, but at the cost of depth. In contrast, the marginalized, physically and mentally impaired survivors cling to ritual, faith, and transcendence — appearing grotesque, yet spiritually alive.

Lopushanskiy’s provocation is ruthless: he suggests that civilization’s survivors may be biologically intact but spiritually hollow, while those deemed “degenerate” preserve humanity’s last connection to transcendence. It is a deeply Russian paradox, echoing centuries of spiritual philosophy and moral pessimism.

The journey to the submerged city becomes a pilgrimage stripped of triumph. When the protagonist finally reaches the museum, there is no catharsis — only recognition of irreparable loss. Civilization can be observed, catalogued, mourned — but not resurrected.

This is not nostalgia. It is mourning without consolation.

Sound, Silence, and the Weight of Time

One cannot discuss Lopushanskiy without addressing his profound use of sound. Dialogue is sparse, often fragmented. Silence dominates, punctuated by ambient noise — wind, footsteps, distant echoes — that reinforces the sense of abandonment. Music, when it appears, feels almost sacred, emerging not to guide emotion but to deepen unease.

Time in his films is elastic and oppressive. Scenes stretch beyond narrative necessity, forcing the viewer to remain present within discomfort. This is not slow cinema for aesthetic pleasure; it is slow cinema as ethical demand. You are not allowed to look away.

This temporal weight is central to Lopushanskiy’s power. His films insist that apocalypse is not an event but a condition — one that unfolds endlessly, without resolution.

Influence, Legacy, and the Silence Around His Name

Despite the profundity of his work, Lopushanskiy remains marginal in global film discourse. He is cited occasionally, screened sporadically, referenced quietly by filmmakers drawn to philosophical dystopia. Yet his influence can be felt in strands of contemporary cinema that reject spectacle in favor of existential inquiry.

His films anticipate ecological cinema, slow dystopia, and post-human narratives long before these became fashionable. They also offer a distinctly Russian counterpoint to Western apocalyptic imagination: where Hollywood emphasizes survival, Lopushanskiy emphasizes accountability.

For cinephiles willing to move beyond canonical lists and festival favorites, Lopushanskiy represents one of the most rewarding discoveries in Russian cinema — a filmmaker whose work does not age because it was never anchored to trends.

Conclusion: Cinema After the End

Watching Konstantin Lopushanskiy is not an easy experience. His films do not comfort, inspire, or entertain in conventional ways. They confront. They linger. They accuse. And they stay with you long after the screen fades to black.

For those who already love Russian cinema, discovering Lopushanskiy feels like uncovering a missing chapter — one written not in the language of triumph or tragedy, but in the quiet handwriting of aftermath. His films remind us that the end of the world is not loud. It is slow, reflective, and filled with unanswered letters.

And perhaps that is why his cinema feels more urgent than ever.