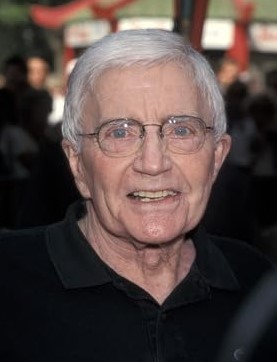

Blake Edwards (1922–2010), a prolific director, screenwriter, and producer, left an indelible mark on American cinema with a career that spanned six remarkable decades and a body of work that effortlessly transcended genres. While often celebrated for his masterful comedic timing and ingenious slapstick, Edwards’s filmography is far more expansive, encompassing thrillers, musicals, and profound dramas. His distinctive style, characterized by sophisticated wit, meticulously crafted visual gags, and a deep, often melancholic, understanding of the human condition, allowed him to explore themes of identity, chaos, and the inherent absurdities of life.

Early Life and Formative Years

Born William Blake Crump on July 26, 1922, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Edwards’s connection to the film industry was deeply rooted in his family. His mother, Lillian, married Jack McEdward, a production manager and assistant director whose father, J. Gordon Edwards, was a prolific silent-film director. This familial legacy provided young Blake with an early immersion into the world of filmmaking. The family relocated to Los Angeles, where Edwards attended Beverly Hills High School, a milieu that further solidified his proximity to Hollywood.

Edwards initially pursued an acting career, appearing in over 50 films, often in uncredited or minor roles. Notable early appearances include “A Guy Named Joe” (1943), “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” (1944), and “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946). While his acting career provided a valuable apprenticeship in film production, his true calling lay behind the camera.

The late 1940s marked a significant shift in Edwards’s professional trajectory as he ventured into writing and producing. His screenwriting debut came with the Western “Panhandle” (1948). This was followed by collaborations on screenplays for films like “All Ashore” (1953) and “The Atomic Kid” (1954), both vehicles for Mickey Rooney. A pivotal moment in his early career was the creation of the highly successful radio series “Richard Diamond, Private Detective” (1949-1953), starring Dick Powell. Edwards served as writer, director, and producer for the show, honing his skills in crafting suspenseful narratives and sharp dialogue, which would later translate effectively to his cinematic work. The series later transitioned to television from 1957 to 1960.

His directorial debut in film arrived in 1955 with the musical comedy “Bring Your Smile Along.” He continued to direct a series of films, gradually refining his unique voice. A significant early commercial success was the World War II comedy “Operation Petticoat” (1959), starring Cary Grant and Tony Curtis. This film showcased Edwards’s growing mastery of comedic orchestration and his ability to work effectively with established stars, setting the stage for his future successes. Edwards also made a notable impact in television with the creation of the stylish detective drama “Peter Gunn” (1958–61), which marked the beginning of his legendary collaboration with composer Henry Mancini, and “Mr. Lucky” (1959–60).

The Breakthrough Years: From “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” to “Days of Wine and Roses”

The early 1960s were transformative for Blake Edwards, as he delivered two of his most enduring and critically acclaimed films, demonstrating a remarkable versatility that defied easy categorization.

In 1961, Edwards directed “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” a romantic comedy-drama that adapted Truman Capote’s novella to the screen. Starring Audrey Hepburn as the iconic Holly Golightly, the film was a massive commercial success and a critical triumph. It solidified Edwards’s reputation as a director capable of handling sophisticated narratives with emotional depth and visual flair. The film’s charm, wit, and underlying poignancy were enhanced by Henry Mancini’s unforgettable score, which earned two Academy Awards, including Best Original Song for “Moon River.” Edwards’s direction skillfully balanced the film’s lighter, comedic moments – particularly the chaotic, yet elegant, parties at Holly’s apartment – with its more dramatic explorations of loneliness and self-discovery. This film proved his adeptness at merging style with substance, creating a timeless classic.

The very next year, Edwards pivoted sharply in genre with “Days of Wine and Roses” (1962). This stark and powerful drama, starring Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick, offered an unflinching look at the devastating effects of alcoholism on a married couple. The film received widespread critical acclaim and garnered five Academy Award nominations, winning for Best Song. “Days of Wine and Roses” was a powerful testament to Edwards’s dramatic capabilities, showcasing his profound understanding of human fragility and suffering. It demonstrated that he was far more than just a purveyor of light comedies, establishing his credibility as a “serious” filmmaker, a label he felt the American industry often hesitated to fully embrace due to his comedic renown. Concurrently, Edwards also directed “Experiment in Terror” (1962), a suspenseful and stylish thriller that further highlighted his diverse directorial range.

The “Pink Panther” Phenomenon and the Peter Sellers Partnership

Without a doubt, Blake Edwards’s most globally recognized and commercially successful creation is the “Pink Panther” film series, which commenced with “The Pink Panther” in 1963. This comedy-mystery introduced the world to the endearingly inept and perpetually flustered French Inspector Jacques Clouseau, a character immortalized by the unparalleled comedic genius of Peter Sellers. The film was an instant hit, spawning a franchise that would comprise nine installments, with Edwards writing and directing all but one, extending over three decades.

The collaboration between Edwards and Sellers, while often turbulent and marked by strong personalities, was undeniably a creative force. Edwards’s meticulous planning of comedic sequences provided the framework for Sellers’s improvisational brilliance, leading to some of cinema’s most iconic physical comedy and character-driven humor. Edwards understood how to fully utilize Sellers’s unique talents for slapstick and mimicry, allowing for moments of spontaneous chaos that became the hallmark of Clouseau’s antics. The early films in the series, including “The Pink Panther” and “A Shot in the Dark” (1964), are quintessential 1960s cinematic works, defined by their vibrant color palettes, international settings, Mancini’s distinctive jazz scores, and intricate comedic timing.

Beyond the “Pink Panther” series, Edwards and Sellers collaborated on one other significant project: “The Party” (1968). This highly experimental and often surreal satire of Hollywood culture featured Sellers as Hrundi V. Bakshi, an Indian actor who, through a series of mishaps, finds himself accidentally invited to a lavish Hollywood party, where his bumbling actions lead to ever-escalating chaos. “The Party” was a stylistic departure for Edwards, relying heavily on improvisation and a minimalist plot to deliver its comedic punch. While it achieved success, the film later drew criticism for Sellers’s use of “brownface,” a practice that became increasingly controversial over time.

While the “Pink Panther” series brought Edwards immense international fame and box-office success, it also inadvertently contributed to a perception within the industry that he was primarily a comedy director. This pigeonholing, despite his proven dramatic prowess, often frustrated Edwards, who felt his serious work was undervalued by American studios.

The Independent Spirit: Navigating Hollywood’s Challenges

Throughout his career, Blake Edwards was known for his independent spirit and his willingness to challenge the conventional wisdom of Hollywood studios. He frequently clashed with executives over creative control, budgets, and final cuts, a struggle that often mirrored the themes of chaos versus order found in his films. This ongoing tension with the studio system became the explicit subject of “S.O.B.” (1981), a scathing black comedy that satirized his own negative experiences while making the lavish, yet commercially disastrous, musical “Darling Lili” (1970). “Darling Lili,” starring his wife Julie Andrews, was a massive financial failure that strained Edwards’s relationship with Paramount, leading to a period where “Pink Panther” sequels were often his only consistent hits. “S.O.B.” was Edwards’s defiant, cathartic response—a cynical yet uproariously funny indictment of the excesses and compromises inherent in the Hollywood machine.

The late 1970s marked a significant commercial comeback for Edwards with the release of “10” (1979). This romantic comedy, which he also wrote and produced, explored themes of male mid-life crisis, societal obsession with youth and beauty, and the pursuit of idealized romance. Starring Dudley Moore and introducing Bo Derek as an overnight sex symbol, “10” was a critical and commercial smash. It not only re-established Edwards’s reputation as a relevant and insightful filmmaker but also showcased his ability to tap into contemporary social anxieties with comedic precision.

In 1982, Edwards delivered another major triumph with “Victor/Victoria,” a sophisticated musical comedy starring Julie Andrews. Andrews portrayed a struggling singer in 1930s Paris who finds success by pretending to be a male female impersonator. The film was a critical and commercial darling, earning Edwards an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. “Victor/Victoria” further explored Edwards’s recurring fascinations with gender identity, role-playing, and societal expectations, all wrapped in a witty, charming, and musically vibrant package. Edwards later successfully adapted “Victor/Victoria” into a Broadway musical, with Andrews reprising her iconic role, demonstrating his versatility across different media.

Edwards’s later filmography continued to explore personal themes, sometimes with mixed results. “That’s Life!” (1986), co-written with his psychotherapist, offered a more introspective and often melancholy look at the challenges of aging and mortality, drawing on his own life experiences and starring his wife and Jack Lemmon. While some of his later films faced critical indifference or studio interference, such as “A Fine Mess” (1986) and “Switch” (1991), his commitment to exploring complex human experiences through his distinctive comedic and dramatic lens remained steadfast. “Switch,” which featured a chauvinistic advertising executive who dies and is reincarnated as a woman (Ellen Barkin), directly confronted themes of gender roles and empathy, even if it was not universally lauded.

Directorial Style, Themes, and Artistic Sensibility

Blake Edwards’s directorial style is immediately recognizable and profoundly influential. He was a master of visual comedy, employing intricate gag construction, impeccable timing, and a fluid, often tracking, camera to create elaborate and frequently chaotic comedic sequences. His films are replete with physical slapstick, a clear homage to silent film comedians, which he seamlessly integrated with sharp, witty dialogue and character-driven humor. Edwards held a deep belief in the intrinsic link between pain and comedy, often illustrating how characters’ misfortunes, humiliations, and struggles could elicit laughter, thereby making the audience connect with their vulnerability. This philosophy is evident in the countless pratfalls, explosions, and mishaps endured by characters like Inspector Clouseau or Professor Fate in “The Great Race.”

Beyond the overt humor, Edwards’s comedies often possessed a profound philosophical underpinning. He was consistently drawn to the tension between highly ordered, controlled existences and those characterized by anarchy and chaos. His protagonists frequently found themselves caught in this conflict, often learning to embrace a degree of chaos to “loosen up” or, conversely, realizing the value of social conventions after a period of wild abandon. This exploration of personal transformation, often through a modification of attitude and a realignment of self-image, formed the dramatic core of much of his work, with changes in character roles reflecting deeper psychological shifts.

Edwards’s wit was often described as “clever, quirky, and mechanical,” serving not just for laughs but as a subtle means for characters to avoid direct communication of their true feelings and needs, thereby hinting at deeper emotional currents. He possessed an acute eye for detail, imbuing his visual compositions with significant meaning, where the appearance of objects frequently suggested their underlying essence. His adept use of the CinemaScope format was particularly noteworthy, allowing him to balance dramatic weight with absurdist comedic flourishes, creating a grand, theatrical feel for his spectacles.

While his comedic genius garnered him widespread acclaim, Edwards’s capacity to strip away the humor and deliberately explore other genres with keen, dramatic insight was a hallmark of his versatility as a writer and director. He explored complex themes such as identity, societal pressures, the inherent absurdities of modern life, and the intricate dynamics of human relationships. His films, despite their frequent comedic tone, were often morally ambiguous, less concerned with clear-cut notions of good and evil and more with human folly as a manifestation of a larger, often chaotic, universe. His ability to blend these elements made his work uniquely rich and enduring.

Key Collaborations and Personal Life

Blake Edwards forged several significant and enduring collaborations throughout his career. His partnership with the legendary composer Henry Mancini was arguably the most significant, with Mancini’s iconic, jazz-infused scores becoming synonymous with Edwards’s films, most notably the “Pink Panther” series (the “Pink Panther Theme” is one of the most recognizable film scores of all time) and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” Mancini’s music provided a crucial atmospheric and emotional layer to Edwards’s visual storytelling. Edwards also cultivated a loyal troupe of actors and technicians, including Peter Sellers, Jack Lemmon, and Julie Andrews, with whom he frequently worked, fostering a sense of creative continuity.

His most profound personal and professional collaboration was with actress Julie Andrews. They married in 1969, a union that lasted 41 years until Edwards’s death in 2010. Their professional synergy was remarkable, leading to a string of notable films including “Darling Lili” (1970), “The Tamarind Seed” (1974), “10” (1979), “S.O.B.” (1981), and “Victor/Victoria” (1982). Andrews often provided a unique balance to Edwards’s more cynical or chaotic tendencies, allowing him to explore musical and dramatic genres alongside his comedic strengths. She helped broaden his artistic palette, and their shared life experiences often directly influenced the themes and narratives of their joint projects, particularly in films like “That’s Life!”

Edwards had two children, Jennifer and Geoffrey, from his first marriage to Patricia Walker (1953-1967). He and Julie Andrews adopted two Vietnamese children, Amy and Jo, creating a blended family. Beyond his filmmaking endeavors, Edwards was also a highly accomplished painter and, in mid-life, took up sculpting, with his bronze works garnering critical praise in various exhibitions. This artistic versatility underscored his boundless creativity.

Awards, Recognition, and Enduring Legacy

Despite his widespread popularity, commercial success, and critical acclaim for individual films, Blake Edwards received relatively few nominations for major awards during his most active career years. He was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for “Victor/Victoria” in 1983. However, his significant contributions to cinema were ultimately recognized in 2004 when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honored him with an Honorary Award for “his writing, directing, and producing an extraordinary body of work for the screen.” He also received the Preston Sturges Award from the Directors Guild of America and the Writers Guild of America in 1993 for his lifetime achievements.

Blake Edwards’s influence on cinematic comedy and his broader impact on filmmaking are undeniable. He is widely regarded as one of the most important comic stylists of the latter half of the 20th century, influencing generations of directors with his unique blend of deadpan farce, intricate gag construction, and sophisticated comedic timing. Critics like Andrew Sarris noted his auteurist control, stating that Edwards’s “personality and script dominate… the way Lubitsch’s personality once dominated Cukor’s One Hour With You.”

His films, whether comedic or dramatic, offered complex, multi-layered entertainment that often defied easy genre classification. Edwards was a filmmaker who continually challenged himself, reinventing his style and themes throughout his sixty-year career. He consistently found new avenues for artistic expression, fueling his creativity until his final years. While his career was sometimes marked by well-documented clashes with the Hollywood studio system and occasional critical missteps, his work consistently demonstrated a singular artistic vision and a courageous willingness to explore challenging themes with both humor and pathos.

At the time of his death on December 15, 2010, at the age of 88, due to complications from pneumonia, Edwards was still actively involved in creative projects, reportedly working on two Broadway musicals—one based on the “Pink Panther” series and an original comedy. This speaks volumes about his enduring passion for storytelling and his tireless creative spirit.

Blake Edwards’s legacy is that of a versatile, innovative, and deeply humanistic filmmaker. His ability to seamlessly blend humor and pain, to orchestrate elaborate visual comedies, and to craft compelling narratives across a wide spectrum of genres ensures his enduring relevance in the history of cinema. His extensive filmography stands as a testament to a unique artistic voice, one that dared to be both profoundly funny and remarkably insightful, often challenging societal norms and leaving audiences simultaneously entertained, intellectually stimulated, and emotionally moved. He remains a celebrated figure whose work continues to resonate, solidifying his place as a true master of American filmmaking